Vestibulaire therapie en visuele training

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van vestibulaire therapie en visuele training bij aanhoudende klachten na licht THL?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg vestibulaire revalidatie bij patiënten met aanhoudende klachten na licht THL duidelijke vestibulo(-oculaire) symptomen ervaren.

Wees er daarbij van bewust dat vermindering van vestibulo-oculaire symptomen nog geen verbetering van functioneren of van participatie hoeft te betekenen.

Wees terughoudend met het toepassen van visuele training bij patiënten met aanhoudende klachten na licht THL.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Het doel van deze uitgangsvraag was om te achterhalen wat de toegevoegde waarde van visuele training en/of vestibullaire interventies bij patiënten met aanhoudende klachten na licht THL. De evidentie bestaat uit een systematische review over alleen vestibulo-oculaire interventies met twee geschikte RCTs, en een RCT die na de oorspronkelijke zoekperiode werd toegevoegd. Binnen deze studies werden verschillende vestibulo-oculaire interventies toegepast, gedurende minimaal 6 tot maximaal 8 weken met een maximale follow-up duur van 6 maanden, waardoor er geen duidelijke uitspraken over lange-termijn effecten kunnen worden gedaan.

Bewijs voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat symptom burden was laag vanwege beperkingen in studieopzet (risk-of-bias) en kleine studiepopulaties. Ook was de uitkomstmaat voor symptom burden indicatief voor het totaal aantal klachten, maar niet specifiek voor vestibulo-oculaire klachten. Het bewijs voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten functioneren en participatie was laag tot zeer laag. Daarom kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen harde conclusies geformuleerd worden over de effecten van vestibulaire therapie en visuele training.

Het verband tussen de stoornissen in het vestibulo-oculaire systeem en de klachten en de beperkingen die patiënten in functioneren en participatie ervaren, is nog niet duidelijk in de literatuur omschreven. Wel is waarschijnlijk dat er mogelijk ook andere factoren hierbij een rol spelen (zie module beïnvloedende factoren).

Visuele training

Er werden geen geschikte studies gevonden naar het effect van visuele training. In een aantal observationele en beschrijvende studies (die om die reden niet zijn meegenomen in de literatuursamenvatting) wordt wel een effect beschreven van visuele training. Dit betreffen echter kleine studies waarin vaak niet is beschreven hoe de gevonden verbetering gerelateerd is aan een klinisch relevant effect. Zo toonde Ciuffreda (2008) in een observationele studie aan dat 90% van de patiënten met een licht THL (n=30) minder symptomen rapporteerden samen met een beter leesvermogen na een visuele training (van variabele duur). Daarnaast liet Thiagarajan (2014) in een cross-over experimentele studie (n=12 licht THL en PCS in chronische fase 1 jaar na trauma) het effect zien van een computer-based training (2 keer per week gedurende 6 weken) van diverse oculomotore componenten op aanwezige klachten. In andere afgeleide publicaties werd separaat het effect van dezelfde training op de accommodatie en oogvolgbewegingen bij dezelfde groep beschreven (Ciuffreda, 2017; Thiagarajan, 2014). De klinische relevantie van de bevindingen bij deze kleine groep zijn echter niet duidelijk.

In een recenter review (Watabe, 2019) werd geconcludeerd dat oculomotore training mogelijk enig effect kan hebben maar dat er weinig studies zijn waarbij de behandeling specifiek is gericht op de verschillende oogbewegingsstoornissen die aanwezig kunnen zijn (zoals beperkingen bij de fixatie, saccades, volgbewegingen en accommodatie). Ook de samenhang van dergelijke oogbewegingsstoornissen met de klachten van patiënten is onvoldoende uitgezocht. In de praktijk worden naast inzet van visuele training ook andere interventies, zoals inzet (prisma)bril toegepast. In de literatuur werd voor deze interventie geen evidentie gevonden.

Concluderend is er onvoldoende bewijs voor het toepassen van visuele training. Het is van belang om de verschillende componenten waar oogbewegingsstoornissen uit kunnen bestaan meer systematisch te determineren om daarmee ook vast te stellen welke stoornis verantwoordelijk is voor de aanwezige klachten van de patiënten. Alleen dan is het mogelijk om in een grotere gerandomiseerde studies het effect van een interventie objectief te kunnen vaststellen.

Vestibulaire therapie

Vestibulaire therapie is voornamelijk gericht op klachten van duizeligheid en balans stoornissen. De behandeling van duizeligheid heeft verschillende invalshoeken door het toepassen van habituatie (blootstelling aan symptoom uitlokkende stimuli), adaptatie (training van niet aangedane onderdelen van het vestibulaire systeem) en substitutie (oefeningen met compensatoire oogbewegingen) (Nagib, 2019). Vaak worden in studies combinaties van verschillende behandelingswijzen toegepast.

De studies uit de literatuursamenvatting pasten allen (fysiek) vestibulaire therapie toe, gedurende maximaal 8 weken.

Naast de fysieke interventies gericht op verbetering van duizeligheid en balans zijn er ook recentere studies die gebruik maken van virtual/augmented reality als onderdeel van een interventie bij balansklachten. Echter is het bewijs hiervan nog erg onzeker. Zo bleken in de vroege fase na licht THL-balansproblemen na een met op virtual reality gebaseerde interventie vergeleken met fysiek balanstraining in beide groepen significant te verbeteren (Cuthbert 2014), wat mogelijk ook een deel spontaan herstel suggereert. Vergelijkbare bevindingen in de chronische fase werden gevonden door Straudi (2017), die video-gaming therapie vergeleek met balansplatform therapie en Tefertiller (2022), die virtual reality games met inspanningstraining (treadmill training) vergeleek met inspanningstraining alleen en standaardzorg. In de laatste twee studies werd ernst van licht THL echter niet gespecificeerd. Ook bestaat de mogelijkheid tot het zelfstandig uitvoeren van vestibulaire revalidatie, zonder begeleiding, conform de aanbeveling in de NHG standaard duizeligheid. Dit geldt specifiek voor klachten van draaiduizeligheid, die langer dan 1 maand duren.

Er zijn relatief veel studies in specifieke subcategorieën van traumatisch hersenletsel verricht zoals sporters of militairen. Hoewel de oorzaak van licht THL bij sporters (subconcussive impact) en militairen (blast injury) anders kan zijn dan bij licht THL in de algemene bevolking (door val of verkeer), en zowel sporters als militairen vaak een jongere leeftijd en ander fysiek uitgangsniveau hebben dan de algemene categorie van licht THL, kunnen studies in deze subgroepen relevante informatie opleveren voor het toepassen van therapieën. Er zijn echter weinig goed verrichte RCT’s op dit gebied. In een retrospectieve studie

onderzocht Alsalaheen (2010) het effect van vestibulaire revalidatie op duizeligheidheidsklachten na een licht THL bij 114 sporters (leeftijd 8-73 jaar). Er was een effect aantoonbaar op de klachten van balans en duizeligheid (maar het aantal sessies varieerde erg sterk).

Concluderend kan gesteld worden dat naast de vestibulaire revalidatie door middel van fysieke vestibulaire therapie, zoals interventies binnen de fysiotherapie, ook nieuwe toepassingen, zoals virtual/augmented reality, een effect kunnen hebben op zowel klachten van duizeligheid als balansstoornissen.

Over het effect van vestibulaire therapie op kwaliteit van leven is nog weinig bekend. Onlangs werd in een RCT bij patiënten met mild-moderate THL (n=65) met duizeligheids- en balansproblemen aangetoond dat vestibulaire revalidatie een duidelijke verbetering van kwaliteit van leven gaf (Søberg, 2021). Opvallend is dat het niet alleen fysieke oefeningen betrof, maar een combinatie van fysieke oefeningen met interventies gericht op coping met de duizeligheids- en balansproblemen. Dit suggereert dat er nog andere mechanismen bijdragen aan herstel, wat ondersteund wordt door hun bevinding dat ook de mate van psychologische stress en het aantal symptomen bij aanvang van de studie bijdroegen aan de verbetering van kwaliteit van leven.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Duidelijk is dat vestibulaire, oculaire en vestibulo-oculaire symptomen veel voorkomen na licht THL in de chronische fase en hun duidelijke weerslag op het functioneren van patiënten hebben (Xiang, 2022). Juist het vrijwel ontbreken van een wetenschappelijk onderbouwde behandeling maakt dat er momenteel veel verschillende interventie door verschillende zorgprofessionals wordt aangeboden, waarvan het effect niet bewezen is en waarover dan ook geen duidelijk advies door de zorgverlener kan worden gegeven aan de patiënt.

Belangrijk is dat patiënten weten dat de evidentie voor veel verschillende behandelingen er momenteel nog niet is en dat de vooruitgang die patiënten aangeven nog niet goed is te meten of te relateren aan de specifieke interventies. Wel is het waarschijnlijk dat er ook andere factoren bij potentiële (ervaren) verbetering een rol spelen. Het is daarom wenselijk dat de interventie onderdeel is van een bredere behandeling die gericht is op meerdere mechanismen van herstel.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten die verbonden zijn aan het verminderd functioneren van patiënten met aanhoudende klachten na licht THL (toename van zorgconsumptie en verminderde participatie, in het bijzonder werkhervatting), kunnen hierbij worden afgezet tegen de kosten van inzet van fysieke therapie door een zorgprofessional, danwel met behulp van virtual augmented reality.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Voor vestibulaire revalidatie bestaat momenteel enig bewijs. Er bestaat echter nog geen exacte beschrijving van de inhoud van vestibulaire revalidatie. Er worden in de literatuur verschillende vestibulo-oculaire interventies toegepast, over het algemeen 1-2 keer per week, gedurende 6 tot maximaal 8 weken, en zowel individueel als in groepsverband. De vestibulaire therapie moet worden toegepast door een zorgprofessional, bijvoorbeeld een fysiotherapeut, met voldoende expertise op dit vlak (zowel wat betreft kennis van het vestibulaire systeem, als kennis van verschillende interventies), waarbij de inzet van visual/augmented reality zeer waarschijnlijk van toegevoegde waarde is/gaat zijn. Hiervoor is dan wel scholing en afspraken nodig om een geprotocolleerde behandeling toe te passen. Gezien het feit dat er ook andere factoren een rol spelen bij de (ervaren) verbetering dan enkel de vestibulo-oculaire interventies, is het wenselijk dat de interventie onderdeel uitmaakt van een bredere, multidisciplinaire behandeling. Dit kan ook onderdeel zijn van een matched-care benadering.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Op basis van de huidige literatuur is er slechts beperkt plaats voor interventies gericht op visuele en vestibulaire klachten, of een combinatie van deze aanhoudende klachten na licht THL. In de studies worden verschillende vestibulaire interventies toegepast, waarbij er in de toekomst mogelijk een rol lijkt te zijn weggelegd voor virtual/augmented reality als aanvulling op de huidige fysieke therapie.

Vestibulaire therapie kan de vestibulo(-oculaire) symptomen doen verminderen, maar de relatie met, of de invloed ervan op functioneren en participatie van de patiënten is nog niet goed onderzocht. In één subgroep, de sport-gerelateerde licht THL, is deze relatie met herstel van sportbeoefening wel duidelijk.

Op basis van de huidige literatuur is er vooralsnog geen plaats voor visuele training na een licht traumatisch (hoofd) hersenletsel in de chronische fase. Ook hier verdient de relatie tussen de visuele stoornissen (onder meer determinatie oogbewegingsstoornissen) en ervaren klachten meer aandacht in de literatuur voordat een gedegen uitspraak kan worden gedaan.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er is toenemend bewijs dat visuele en vestibulaire symptomen blijven bestaan na licht traumatisch hersenletsel. Voor balansprobelmatiek en duizeligheid wordt een incidentie van 80-30% genoemd, welke afneemt in de chronische fase (Xiang 2022). Specifieke visuele klachten zijn bijvoorbeeld wazig zien, moeite met lezen of kijken naar een beeldscherm. Daarnaast kunnen klachten aanwezig zijn van bijvoorbeeld accommodatie- of convergentiestoornissen en fotosensitiviteit. Vestibulaire klachten betreffen duizeligheid en balansstoornissen. Ook kunnen deze klachten gezamenlijk aanwezig zijn, dan is sprake van vestibulo-oculaire klachten.

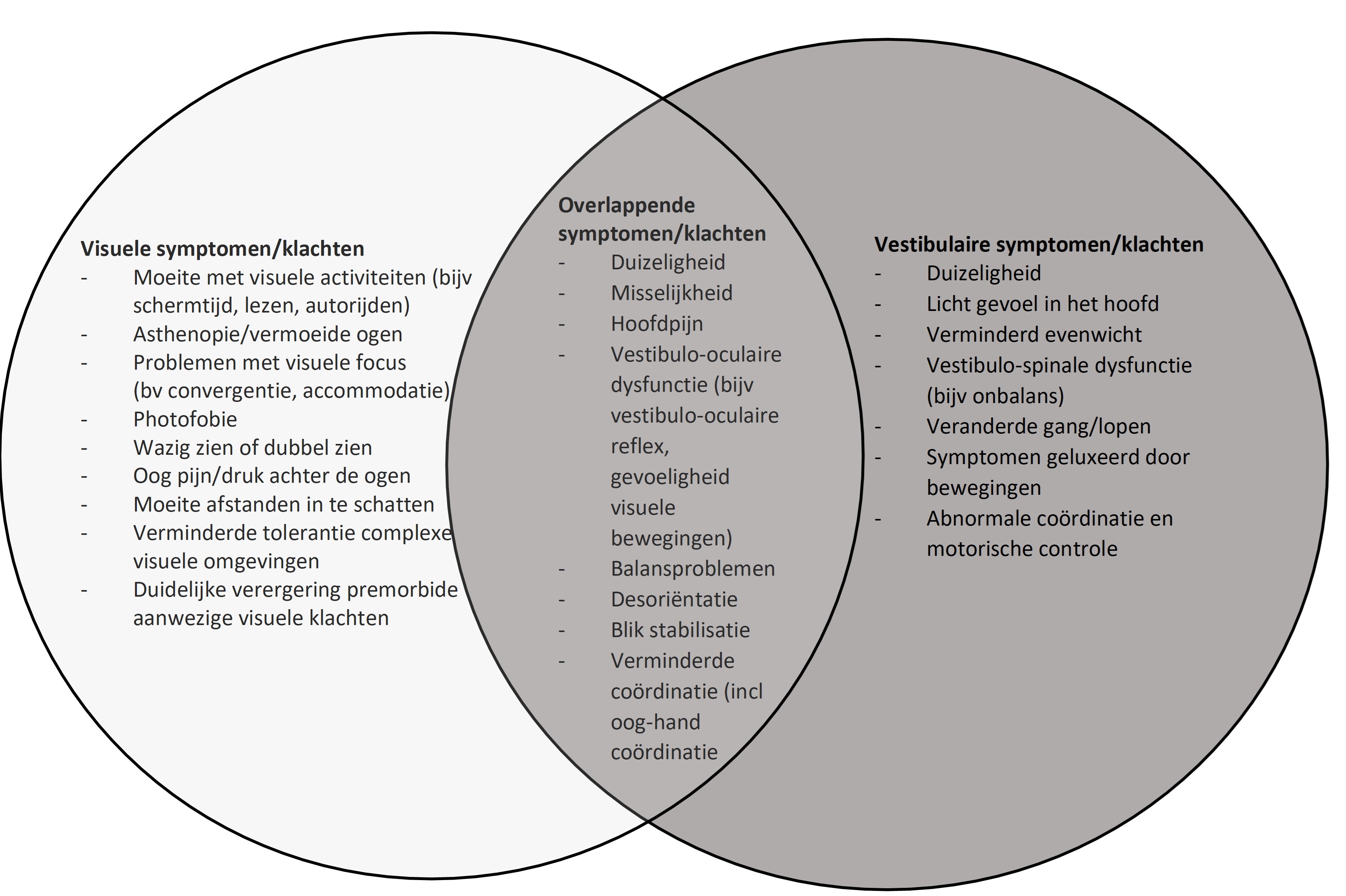

Figuur 1. Ervaren visuele en vestibulaire klachten na licht THL (gebaseerd op figuur uit artikel van Xiang (2022)).

Het vestibulaire systeem (bestaande uit een vestibulo-spinale en een vestibulo-oculaire component) (Kontos, 2017; Maskell, 2006) speelt een belangrijke rol bij het handhaven van de balans en de visuele en ruimtelijke oriëntatie Er vindt integratie plaats van perifere prikkeling via het binnenoor en evenwichtsorgaan naar de centrale kernen die signalen integreren voor een optimale houding en balans. Het vestibulaire systeem is ook betrokken bij de oogbewegingen waarvan de vestibulo-oculaire reflex (VOR) een van de belangrijkste is. De samenwerking tussen vestibulaire en visuele systeem draagt bij aan het handhaven van blik- en houdingsstabiliteit tijdens bewegingen, door het voortdurend voorzien van feedback over positie in de ruimte.

Onderzoek naar de visus en balans is onderdeel van het algemeen neurologisch onderzoek en wanneer dit niet afwijkend is, kan diagnostisch onderzoek met behulp van gezichtsveldonderzoek, VOR-screening, onderzoek van de balans of een Dix-Hallpike manoevre aanvullende informatie geven. Dit wordt echter niet standaard toegepast (Crampton, 2021). Bij lichamelijk onderzoek wordt niet altijd een verklaring gevonden voor de ervaren klachten van patiënten.

Wanneer er vestibulaire stoornissen aantoonbaar zijn, is revalidatie gericht op perifere of centrale vestibulaire stoornissen mogelijk (Hillier, 2007; Gurley, 2013). Interventies kunnen worden toegepast door een gespecialiseerde zorgprofessional met als doel het vestibulaire systeem te optimaliseren door de oog- hoofd- en lichaamsbewegingen te coördineren om de balans te verbeteren.

Er zijn effecten van zowel vestibulaire therapie als van visuele training beschreven maar er is weinig informatie beschikbaar over de toepassing in de praktijk of van het effect van deze interventies op het algemene functioneren van patiënten. Als gevolg hiervan is er momenteel onvoldoende informatie aanwezig over de beschikbaarheid van een gestandaardiseerde behandeling van visuele klachten en vestibulaire klachten bij patiënten met aanhoudende klachten na licht THL.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

1.1 Symptom burden

|

Low GRADE |

Vestibular rehabilitation may improve symptom burden when compared with no treatment, in patients with mTBI.

Sources: Rytter, 2021 (Kleffelgaard, 2019); Langevin, 2022 |

1.2 Functioning

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of vestibular rehabilitation on functioning when compared with no treatment in patients with mTBI.

Sources: Rytter, 2021 (Kleffelgaard, 2019); Gotshall, 2010; Langevin, 2022 |

1.3 Participation

|

Low GRADE |

Vestibular rehabilitation may improve participation (return to sport) when compared with no treatment, in patients with sport-related concussion, a subgroup of mTBI.

Sources: Rytter, 2021 (Schneider, 2014) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies (summarized in table 1)

1. Vestibular rehabilitation

Rytter (2021) described a systematic review with meta-analysis and guideline recommendation about the effects of nonpharmacological treatment of persistent postconcussion symptoms in adults. A systematic literature search was performed in Embase, Medline, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PEDro, OTseeker and Cochrande Revies (via MEDLINE and Embase) from inception to March 3, 2020. Systematic reviews and primary intervention studies were included if 1) patients were adults with persistent postconcussion symptoms; 2) a control group was included. A total of 19 RCTs were included in the review of Rytter (2021). To answer the PICO of this module, only 2 RCTs (Kleffelgaard, 2019; Schneider, 2014) were eligible since the other RCTs described the effects of systematically offered information and advice, graded physical exercise, spinal manual therapy, psychological treatment or interdisciplinary coordinated rehabilitative treatment. The effects on dizziness, physical functioning, return to sport, anxiety, depression were assessed at the end of treatment and/or after two months of follow-up.

Gottshall (2010) described an observational study about the effects of a vestibular physical therapy program in patients with blast-induced mild traumatic brain injury. A total of 82 soldiers (3,7% women; mean age 24y) who had mTBI secondary to blast injuries and no other associated physical injuries were included in the analysis. Patients were included if they had one of four vestibular disorders (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, exertion-induced dizziness, blast-induced disequilibrium and blast-induced disequilibrium with vertigo). All patients underwent a vestibular physical therapy program, which consisted of exercise procedures that targeted the vestibo-ocular reflex, cervico-ocular reflex, depth perception, somatosensory retraining, dynamic gait and aerobic function. The training was executed twice weekly for one hour in addition to exercises at home on the other days for 8 weeks. The effects were evaluated on perception time, target acquisition, target following, dynamic visual activity and gaze stabilization after 12 weeks.

Langevin (2022) described a randomized controlled trial about the effects of cervicovestibular rehabilitation in adults with mild traumatic brain injury. A total of 60 adults with persistent symptoms after mTBI were randomly allocated to receive a six-week symptom-limited aerobic exercise (SLAE) program (n=30; mean age 38.9y; 67% women) or a six week cervicovestibualr rehabilitation program combined with a SLAE program (n=30; mean age 39.07y; 70% women). Patients received eight supervised treatment sessions in six weeks. Effects were evaluated on the post-concussion symptoms scale (PCSS), the neck disability index (NDI), the headache disability inventory (DHI), the dizziness handicap inventory (DHI), the headache and neck pain numerical pain rating scale (NPRS), the global rating of change (GRC), clearance to return to function and objective measures of cervical range of motion. Five evaluation sessions over 26 weeks (baseline, week 3, 6, 12 and 26) were executed.

Table 1. Study characteristics

|

Study |

Design |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

Outcome measures |

|

|

Kleffelgaard, 2019 |

RCT |

patients with TBI, aged 16– 60 years who reported feelings of dizziness on the Rivermead Post- Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire13 (dizziness score ⩾ 2) and/or had a positive Romberg’s test. |

A group-based vestibular rehabilitation intervention twice weekly for eight weeks and the usual multidisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation comprising clinical examinations by a physiatrist and assessments and follow-ups by a multidisciplinary team if needed (n=33). |

The control group did only receive the usual multidisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation comprising clinical examinations by a physiatrist and assessments and follow-ups by a multidisciplinary team if needed (n=31). |

Specific symptoms and function at the end of treatment and after 2 months of FU. |

|

|

Schneider, 2014 |

RCT |

Patients with persistent symptoms of dizziness, neck pain and/or headaches following a sport-related concussion 12-30 years). |

Cervical spine and vestibular rehabilitation weekly for 8 weeks with care as usual (n=15). |

8 weeks of care as usual (comprising physiotherapy, postural education, range of motion exercises and cognitive and physical rest) (n=14). |

Participation (resumption of sport) at the end of treatment. |

|

|

Gottshall, 2010 |

OBS |

82 soldiers with mTBI secondary to blast injuries and no other associated physical injuries. |

Vestibular physical therapy program (exercise targeting the vestibo-ocular reflex, cervico-ocular reflex, depth perception, somatosensory retraining, dynamic gait and aerobic function). Twice weekly for one hour in addition to exercises at home on the other days for 8 weeks. |

n.a. |

Functioning after 4, 8 or 12 weeks of FU. |

|

|

Langevin, 2022 |

RCT |

60 adults with persistent symptoms after mTBI |

A six week cervicovestibualr rehabilitation program combined with a SLAE program (n=30) |

a six week symptom-limited aerobic exercise (SLAE) program (n=30) |

PCSS, NDI, DHI, NPRS, GRC, clearance to return to function and objective measures of cervical range of motion. Five evaluation sessions over 26 weeks (baseline, week 3, 6, 12 and 26). |

|

|

Abbreviations: RCT; randomized controlled trial, mTBI; mild traumatic brain injury; TBI; traumatic brain injury, FU; follow-up, OBS; observational study, n.a.; not applicable, PCSS; post-concussion symptoms scale, NDI; neck disability index, DHI; headache disability index, NPRS; headache and neck pain numerical pain rating scale, GRC; global rating of change, ABC; Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale, LEFS; Lower Extremity Functional Scale. |

||||||

2. Visual training

No studies were found regarding the effect of visual training.

Results

1.1 Symptom burden

The RCT of Kleffelgaard (2019; n=64) assessed symptom burden by the dizziness handicap inventory (range 0-100, lower score means better outcome). At the end of treatment, data resulted in a mean (standard deviation) score of 32.9 (21.3) in the intervention group and 36.4 (22.7) in the control group. After two months of follow-up data resulted in a mean (standard deviation) score of 32.1 (20.7) in the intervention group and 30.0 (24.3) in the control group. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

The RCT of Langevin (2022; n=60) assessed symptom burden by the total score of Post-Concussion Symptoms Scale (PCSS; range 0-132; lower score means better outcome) Score is indicative of the total number of complaints but not specifically for oculo-vestibular symptoms. In the intervention group, the score decreased from 62.83 (SD 23.69) at baseline down to 17.21 (SD 13.25), 16.46 (SD 16.12) and 13.96 (SD 12.63) after 6, 12 and 26 weeks respectively. In the control group, the score decreased from 61.77 (SD 22.59) at baseline down to 23.85 (SD 19.98), 16.18 (SD 14.45) and 14.67 (SD 16.85) after 6, 12 and 26 weeks respectively. These differences were not considered clinically relevant. Furthermore, they are indicative of the total number of complaints but not specifically for oculo-vestibular symptoms.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure symptom burden started at high because it was based on RCTs, but was downgraded by two levels to low because of lack of concealment allocation and presence of comorbidities related to eligibility criteria (-1, risk of bias); and a low number of included patients (-1, imprecision).

1.2 Functioning

The RCT of Kleffelgaard (2019; n=64) assessed functioning by the high level mobility assessment tool for traumatic brain injury (range 0-54; higher score means better outcome). At the end of treatment, data resulted in a mean (standard deviation) score of 47.6 (7.0) in the intervention group and 41.2 (12.3) in the control group. After two months of follow-up, data resulted in a mean (standard deviation) score of 47.3 (8.2) in the intervention group and 44.3 (9.6) in the control group. Only at the end of treatment, the difference was clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

The observational study of Gotshall (2010; n=82) assessed functioning by the Neurocom in Vision Tunnel in which vestibular-visual-cognitive battery tests were performed in a darkened room with a viewing distance of 10 feet. Participants were military with blast induced mTBI. For target following, data resulted in an improvement from 9 degrees/second pre-intervention to 13 degrees/second post-intervention, which is better than normative levels (12 degrees/second). For dynamic visual acuity, data (presented as logMAR) resulted in an improvement from 0.27-0.33 pre-intervention to 0.18-0.20 post-intervention, which is lower than normative levels (≤ 0.2). These differences were clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

The RCT of Langevin (2022; n=60) assessed functioning by the Vestibula Ocular Motor Scale (VOMS; range 0-10; lower score means better outcome), the Head Impulse Test (HIT; % positive; lower score means better outcome) and the Flexion-Rotation Test (FRT (right-left difference; lower score means better outcome). From the VOMS, different subscales were extracted (near point convergence (NPC) distance, horizontal vestibular ocular reflex (H-VOR), visual motion sensitivity test (V-VOR).

At six weeks, all subscales distracted from the VOMS, as well as the HIT and FRT, improved in the intervention group compared to the control group (see Table 1). These differences were clinically relevant in favor of the intervention group.

However, at 12 weeks the clinically relevant differences for the VOMS did not last. Still, the HIT improved clinical relevantly in favor of the intervention (37% to 0% in the intervention group (-27%) compared to 63% to 44% in the control group (-19%)). Also, the FRT improved clinically relevantly in favor of the intervention (12.73 (SD 8.89) to 2.68 (SD 5.40) in the intervention group (-10,05), compared to 10.27 (SD 9.12) to 11.16 (SD 10.02) in the control group (+0,89).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functioning started at low because it was based on two RCTs and an observational study, but was downgraded to very low because lack of concealment allocation and presence of comorbidities related to eligibility criteria (-1, risk of bias).

1.3 Participation

The RCT of Schneider (2014; n=31) assessed participation by the number of patients assessed ready to return to sport. At the end of treatment, 11/15 (73.3%) patients returned to sport in the intervention group and 1/14 (7.1%) returned to sport in the control group. This difference was clinically relevant in favor of the intervention.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function started at high because it was based on an RCT, but was downgraded by two levels to low because of low number of included patients (-2, imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What is the effect of vestibular rehabilitation, visual training or vestibo-ocular training after mild traumatic brain injury in patients with remaining complaints after three months on symptom burden, functioning, mood, anxiety and participation?

P: Patients with remaining complains after mild traumatic brain injury after three months;

I: Vestibular rehabilitation, visual training, vestibulo-ocular training;

C: Rest, no intervention;

O: Symptom burden, functioning, participation.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered symptom burden as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and functioning, and participation as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Symptom burden: Visual and/or vestibular symptoms.

- Functioning: Visual and/or vestibular functioning.

- Participation: Return to activities of daily living, work of sport.

For all outcome measures, the working group defined an absolute difference of 10% on each test scale between the intervention and the control group as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2000 until November12th, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 198 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review and/or meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial (RCT) and observational studies;

- Included adult patients (18+);

- Described vestibular rehabilitation, visual training or vestibular-ocular training as an intervention;

- Described rest or no intervention as a comparison;

- Described at least one of the outcome measures as prescribed in the PICO;

- Included at least 10 patients per treatment arm.

32 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 29 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and four studies were included. Furthermore, one RCT was added to the analysis, this it was published after the search date (Langevin, 2022).

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

The following intervention types were defined by the working group:

- Vestibular rehabilitation (n=3);

- Visual therapy (n=0)

Referenties

- Alsalaheen BA, Mucha A, Morris LO, Whitney SL, Furman JM, Camiolo-Reddy CE, Collins MW, Lovell MR, Sparto PJ. Vestibular rehabilitation for dizziness and balance disorders after concussion. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010 Jun;34(2):87-93. doi:10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181dde568. PMID: 20588094.

- Ciuffreda KJ, Rutner D, Kapoor N, Suchoff IB, Craig S, Han ME. Vision therapy for oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain injury: a retrospective analysis. Optometry. 2008 Jan;79(1):18-22. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2007.10.004. PMID: 18156092.

- Ciuffreda KJ, Yadav NK, Thiagarajan P, Ludlam DP. A Novel Computer Oculomotor Rehabilitation (COR) Program for Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (mTBI). Brain Sci. 2017 Aug 9;7(8):99. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7080099. PMID: 28792451; PMCID: PMC5575619.

- Cohen A. The role of optometry in the management of vestibular disorders. Brain Injury Professional. 2005;2(3):8-10.

- Crampton A, Teel E, Chevignard M, Gagnon I. Vestibular-ocular reflex dysfunction following mild traumatic brain injury: A narrative review. Neurochirurgie. 2021 May;67(3):231-237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2021.01.002. Epub 2021 Jan 19. PMID: 33482235.

- Cuthbert JP, Staniszewski K, Hays K, Gerber D, Natale A, O'Dell D. Virtual reality-based therapy for the treatment of balance deficits in patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2014;28(2):181-8. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.860475. PMID: 24456057.

- Gottshall KR, Hoffer ME. Tracking recovery of vestibular function in individuals with blast-induced head trauma using vestibular-visual-cognitive interaction tests. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2010 Jun;34(2):94-7. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e3181dead12. PMID: 20588095.

- Green W, Ciuffreda KJ, Thiagarajan P, Szymanowicz D, Ludlam DP, Kapoor N. Accommodation in mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(3):183-99. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0041. PMID: 20665345.

- Gurley JM, Hujsak BD, Kelly JL. Vestibular rehabilitation following mild traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32(3):519-28. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130874. PMID: 23648606.

- Fox SM, Koons P, Dang SH. Vision Rehabilitation After Traumatic Brain Injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2019 Feb;30(1):171-188. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Oct 31. PMID: 30470420.

- Hillier SL, Hollohan V. Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD005397. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):CD005397. PMID: 17943853.

- Hillier C. Vision rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: A case series. Brain InjuryProfessional. 2005;2(3):30-32.

- Kleffelgaard I, Soberg HL, Tamber AL, Bruusgaard KA, Pripp AH, Sandhaug M, Langhammer B. The effects of vestibular rehabilitation on dizziness and balance problems in patients after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2019 Jan;33(1):74-84. doi: 10.1177/0269215518791274. Epub 2018 Jul 30. PMID: 30056743. Kontos AP, Deitrick JM, Collins MW, Mucha A. Review of Vestibular and Oculomotor Screening and Concussion Rehabilitation. J Athl Train. 2017 Mar;52(3):256-261. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.05. PMID: 28387548; PMCID: PMC5384823.

- Langevin P, Frémont P, Fait P, Dubé MO, Bertrand-Charette M, Roy JS. Cervicovestibular Rehabilitation in Adults with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Neurotrauma. 2022 Apr;39(7-8):487-496. doi: 10.1089/neu.2021.0508. PMID: 35102743.

- Maskell F, Chiarelli P, Isles R. Dizziness after traumatic brain injury: overview and measurement in the clinical setting. Brain Inj. 2006 Mar;20(3):293-305. doi: 10.1080/02699050500488041. PMID: 16537271.

- Nagib S, Linens SW. Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy Improves Perceived Disability Associated With Dizziness Postconcussion. J Sport Rehabil. 2019 Sep 1;28(7):764-768. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2018-0021. PMID: 30040008.

- Rytter HM, Graff HJ, Henriksen HK, Aaen N, Hartvigsen J, Hoegh M, Nisted I, Næss-Schmidt ET, Pedersen LL, Schytz HW, Thastum MM, Zerlang B, Callesen HE. Nonpharmacological Treatment of Persistent Postconcussion Symptoms in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis and Guideline Recommendation. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Nov 1;4(11):e2132221. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32221. PMID: 34751759; PMCID: PMC8579233.

- Schneider KJ, Meeuwisse WH, Nettel-Aguirre A, Barlow K, Boyd L, Kang J, Emery CA. Cervicovestibular rehabilitation in sport-related concussion: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Sep;48(17):1294-8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports- 2013-093267. Epub 2014 May 22. PMID: 24855132.

- Søberg HL, Andelic N, Langhammer B, Tamber AL, Bruusgaard KA, Kleffelgaard I. Effect of vestibular rehabilitation on change in healicht THL-related quality of life in patients with dizziness and balance problems after traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2021 Apr 21;53(4):jrm00181. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2823. PMID: 33842981; PMCID: PMC881483

- Straudi S, Severini G, Sabbagh Charabati A, Pavarelli C, Gamberini G, Scotti A, Basaglia N. The effects of video game therapy on balance and attention in chronic ambulatory traumatic brain injury: an exploratory study. BMC Neurol. 2017 May 10;17(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0871-9. PMID: 28490322; PMCID: PMC5424286.

- Tefertiller C, Hays K, Natale A, O'Dell D, Ketchum J, Sevigny M, Eagye CB, Philippus A, Harrison-Felix C. Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial to Address Balance Deficits After Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019 Aug;100(8):1409- 1416. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.03.015. Epub 2019 Apr 19. PMID: 31009598; PMCID: PMC8594144.

- Thiagarajan P, Ciuffreda KJ. Effect of oculomotor rehabilitation on accommodative responsivity in mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(2):175-91. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2013.01.0027. PMID: 24933717.

- Thiagarajan P, Ciuffreda KJ. Versional eye tracking in mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI): effects of oculomotor training (OMT). Brain Inj. 2014;28(7):930-43. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.888761. Epub 2014 Mar 21. PMID: 24826956.

- Watabe T, Suzuki H, Abe M, Sasaki S, Nagashima J, Kawate N. Systematic review of visual rehabilitation interventions for oculomotor deficits in patients with brain injury. Brain Inj. 2019;33(13-14):1592-1596. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1658225. Epub 2019 Aug 27. PMID: 31455098.

- Xiang L, Bansal S, Wu AY, Roberts TL. Pathway of care for visual and vestibular rehabilitation after mild traumatic brain injury: a critical review. Brain Inj. 2022 Jul 3;36(8):911-920. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2022.2105399. Epub 2022 Aug 2. PMID: 35918848.

Evidence tabellen

Systematic review

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Rytter, 2021 |

SR and meta-analysis of SR and primary intervention studies

Literature search up to March 2020

A: Kleffelgaard, 2019 B: Schneider, 2014

Study design: A: RCT B: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Norway B: Canada

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Any potential conflicts of interests were declared before initiating the work and can be accessed online in Danish.22 The draft of the clinical guideline was peer reviewed by 2 external reviewers as well as in a public hearing. |

Inclusion criteria SR: 1) be intervention studies within the areas of the predefined clinical questions, (2) include a control group, and (3) focus on symptoms after concussion or mTBI. Studies including both concussion or mTBI and moderate to severe TBI were only included if it was possible to extract separate data for the concussion/mTBI population. Participants had to be aged 18 years or older and be diagnosed with concussion or mTBI. Consent (written or oral) from the participants was not obtained, as the study only used data from previously published studies. Studies including adolescents were included only if adolescent participants represented a minority of the study sample.

19 RCTs included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 64 patients, 39.4 yrs B: 31 patients

Sex: A: 29.7% Male B: 58.1% Male

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: group-based vestibular rehabilitation intervention twice weekly for eight weeks and the usual multidisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation comprising clinical examinations by a physiatrist and assessments and follow-ups by a multidisciplinary team if needed. B: Patients in the intervention group received customized VRT and cervical spine therapy and weekly treatment sessions for up to 8 wk.

|

Describe control:

A: The control group did not receive any rehabilitation intervention in place of the group-based vestibular rehabilitation intervention and the usual multidisciplinary outpatient rehabilitation comprising clinical examinations by a physiatrist and assessments and follow-ups by a multidisciplinary team if needed. B: Patients in the control group only received cervical spine therapy and weekly treatment sessions for up to 8 wk.

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 2 Months after treatment. B: End of treatment.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: End of treatment: 1/0 2 months follow-up: 5/3 B: n.r.

|

Symptom burden Defined as dizziness measured by the dizziness handicap inventory (range 0-11; lower is better)

Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: A: End of treatment: 2 Months after treatment: 2.10 [-9.82 – 14.02] favoring control. B: n.r.

Functioning Defined as the level of mobility by the high level mobility assessment tool for traumatic brain injury (range 0-54; higher is better).

Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: A: End of treatment: 2 Months after treatment: B: n.r.

Participation Defined as the number of patients who returned to sport.

Effect measure: risk ratio [95% CI]: A: n.r.

|

Autor’s conclusion There is an urgent need for more methodologically robust research evaluating the outcomes of nonpharmacological treatments for persistent symptoms after concussion or mTBI. Given the best available evidence to date, and based on the findings of this systematic review and meta-analysis, active management and treatment of PPCS is recommended, both through individual disciplines targeting specific problems and through interdisciplinary rehabilitation. There was agreement on this recommendation across the available guidelines, including the one presented here, regardless of their applied methodology. |

Randomized controlled trials

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Langevin, 2022 |

Type of study: A Randomized Clinical Trial.

Setting and country: Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Alicht THLough PL (20%) and Pfa (12%) are the owners of a private Concussion Clinic involved in the treatment of patients in this trial. The clinic and the authors did not financially support the project nor did they gain or lose financially from the publication of this article.

Funding was provided by the Re´seau Provincial de Recherche en Adaptation-Re´adaptation (REPAR) and by the Ordre Professionnel de la physiothe´rapie du Que´bec (OPPQ). Trial sponsors are REPAR (repar .irglm@ssss.gouv.qc.ca) and OPPQ (physio@oppq .qc.ca). The funding agency/sponsor had no role in the study design, writing the manuscript, or in the decision to submit for publication. |

Inclusion criteria: (1) TBI in the past three to 12 weeks with ongoing symptoms including at least dizziness, neck pain, and/or headaches that started 72 h or less after the trauma; (2) at least one of the following cognitive symptoms: feeling slowed down, feeling like in a fog, ‘‘don’t feel right,’’ difficulty concentrating, difficulty remembering, and confusion that started 72 h or less after the trauma; (3) at least one abnormality during the cervical physical examination (e.g., tenderness/spasm/pain on segmental testing, or reduced motion), vestibular evaluation (e.g., Dix hallpike or vestibulo-ocular reflex [VOR] tests), or ocular motor evaluation (e.g., convergence, smooth pursuits, or saccades).

Exclusion criteria: (1) >30 min of loss of consciousness; (2) more than 24 h of post-traumatic amnesia; (3) Glasgow Coma Scale score lower than 13 more than 30 min after the injury; (4) radiological evidence of subdural hemorrhage, epidural hemorrhage, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, and cerebral or cerebellar contusion; (5) post-injury hospitalization for more than 48 h; (6) fracture; (7) neurological condition other than mTBI; (8) comorbidities of cardiovascular or respiratory systems; (9) received compensation from a third party payer.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 30 Control: 30

Important prognostic factors2: age (SD): I: 38.9 (14.56) C: 39.07 (12.63)

Sex: I: 675 F C: 70% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Intervention: canalith repositioning maneuver, vestibular adaptation, ocular motor exercises, balance and/or habituation exercises combined with the intervention in the control group. |

General advice by all clinicians (counselling and individual recommendation on activation), neuropsychology (two sessions of clinial neuropsychologist testing and advice and recommendations about cognitive activation and activity of daily living), one session of kinesiology (clinial evaluation of symptomatic response to aerobic exertion on a stationary bike), 8 sessions of physiotherapy.

|

Length of follow-up: 3, 6, 12 and 26 weeks.

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 2 (6.7%) Reason: Treatment site too far from home and COVID 2020 lockdown.

Control: 2 (6.7%) Reason: COVID 2020 lockdown.

Incomplete outcome data: 6-week Intervention 4 (12.3%) Control: 9 (32.1%

12-week Control: 12 (63.2%)

Reason: objective physical evaluation was not performed.

|

Symptom burden Defined by the Post-Concussion Symptoms Scale (PCSS; range 0-132; lower score means better outcome). Effect measure: mean (SD) intervention/mean (SD) control 6 weeks: 17.21 (13.25)/ 23.85 (19.98)

12 weeks: 16.46 (16.12)/ 16.18 (14.45)

26 weeks: 13.96 (12.63)/ 14.67 (16.85)

Functioning n.r.

Participation n.r.

|

Author’s conclusion Prophylactic use of LEV in the perioperative period is recommended because it is safe and significantly reduces the incidence of seizures in this period. |

|

Gotshall, 2010 |

Type of study: Cohort study.

Setting and country: n.r.

Funding and conflicts of interest: n.r. |

Inclusion criteria: All participants were soldiers who had mTBI secondary to blast injuries sustained in Iraq or Afghanistan, with no other associated physical injuries. The participants were diagnosed as having 1 of 4 vestibular disorders: (1) benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, (2) exertion- induced dizziness, (3) blast-induced disequilibrium, and (4) blast-induced disequilibrium with vertigo.

Exclusion criteria: n.r.

N total at baseline: 82

Important prognostic factors2: age (range): 24 (19-34)

Sex: 3.7% F

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

The VPT program consisted of exercise procedures that targeted the vestibulo-ocular reflex, cervico-ocular reflex, depth perception, somatosensory retraining, dynamic gait, and aerobic function. The vestibulo-ocular reflex, cervicoocular reflex, and depth perception exercises were graded in difficulty, based on velocity of head and object motion, and progression of body positioning from sitting to standing to walking. The SS exercises were graded in difficulty by narrowing the base of support, making the surface uneven, or changing the surface from firm to soft. Walking exercises were graded in difficulty by changing direction, performing with the eyes closed, increasing speed, walking on soft surfaces, or navigating stairs. The aerobic exercise home program was progressively increased by adjusting the time, speed, or distance. All subjects were encouraged to work at their maximum tolerance while performing the VPT. These exercises have been described in detail elsewhere.7 Participants attended VPT twice weekly for 1-hour sessions and were instructed to perform the exercises on a home program basis the other days. |

Group mean pretreatment scores on SOT, MCT, DGI, PT, TA, TF, DVA, and GST were compared with group mean posttreatment scores using a 2-way analysis of variance with standard statistical software (GB-STAT). Significance was defined as P .01. |

Length of follow-up: 4 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

|

Symptom burden n.r.

Functioning Defined by Neurocom in Vision Tunnel in which vestibular-visual-cognitive battery tests were performed in a darkened room with a viewing distance of 10 feet (table 3).

Effect measure: Improvement pre-post intervention

Target following 9 to 13 degrees/second

Dynamic visual acuity (logMAR) 0.27-0.33 to 0.18 – 0.20

Participation n.r.

|

Author’s conclusion In soldiers with mTBI and vestibular disorders caused by blast injuries, many aspects of vestibular-visual-cognitive function recover with VPT. The time course of recovery varies for different aspects of vestibular function. A battery of vestibular-visual-cognitive tests is valuable for establishing initial functional levels and can be used to document improvement. These outcome measures may also be useful to determine return to duty/work status as well as return to physical activity status for military personnel. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Risk-of-bias table for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Rytter, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healicht THLcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Langevin, 2022 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Blocked randomization (block sizes of 2, 4, and 6) was used. Stratification was performed according to sex to ensure women and men were equally represented in each group as it has been shown that women recover more slowly from mTBI |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Group allocations were concealed in sealed, opaque, and sequentially numbered envelopes. |

Probably yes;

Reason: The evaluators and statistician were blinded to treatment groups. The randomisation envelopes were opened at the treatment site by a research assistant. No information was provided about the blinding of participants. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: 4/60 (6.6%) patients were loss to follow-up. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Results of all predefined outcome measures were reported. |

Definitely no;

Reason: The higher cointervention rate in the CTRG introduces a limitation in the study that could have contributed to the lack of group-by-time interaction; Other mTBI prognosis features include comorbidities (i.e., mental healicht THL, anxiety/depression), and those comorbidities are more prevalent in the older population 44 versus younger athletes. Apart from comorbidities related to eligibility criteria such as cardiovascular conditions, comorbidities were not systematically documented. |

Some concerns |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Risk of bias table for interventions studies (cohort studies based on risk of bias tool by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study? |

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables? |

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Gotshall, 2010 |

Definitely no;

Group mean values were compared with normative data previously collected in the laboratory (but not previously published) as part of another study of individuals without vestibular dysfunction. |

Probably no;

Normative data were obtained from 80 participants without vestibular dysfunction. |

Definitely yes;

Normative data for vestibular function tests as a function of age range was presented and was different from the outcome data. |

No information.

|

No information. |

Probably yes;

The testing and VPT were the same for all participants regardless of diagnosis. |

Definitely yes;

We applied a standardized battery of tests at baseline and follow-up for all participants referred for VPT after blast injury. |

Definitely yes;

We applied a standardized battery of tests at baseline and follow-up for all participants referred for VPT after blast injury. |

High |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, 23rd Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, April 5-9, 2014, Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine: March 2014 - Volume 24 - Issue 2 - p e1-e21 doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000087 |

Wrong study design: research presentation abstracts |

|

Alashram AR, Annino G, Raju M, Padua E. Effects of physical therapy interventions on balance ability in people with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. NeuroRehabilitation. 2020;46(4):455-466. doi: 10.3233/NRE-203047. PMID: 32508337. |

Wrong population: severity of TBI not specified |

|

Barton JJS, Ranalli PJ. Vision therapy: Occlusion, prisms, filters, and vestibular exercises for mild traumatic brain injury. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021 Mar-Apr;66(2):346-353. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2020.08.001. Epub 2020 Aug 19. PMID: 32827496. |

Wrong study design: descriptive review |

|

Carrick FR, Clark JF, Pagnacco G, Antonucci MM, Hankir A, Zaman R and Oggero E (2017) Head–Eye Vestibular Motion Therapy Affects the Mental and Physical Healicht THL of Severe Chronic Postconcussion Patients. Front. Neurol. 8:414. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00414 |

Wrong study design: observational study |

|

Cuthbert JP, Staniszewski K, Hays K, Gerber D, Natale A, O'Dell D. Virtual reality-based therapy for the treatment of balance deficits in patients receiving inpatient rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2014;28(2):181-8. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.860475. PMID: 24456057. |

Wrong control group: both received an intervention |

|

Damiano, D. L., Zampieri, C., Ge, J., Acevedo, A., & Dsurney, J. (2016). Effects of a rapid-resisted elliptical training program on motor, cognitive and neurobehavioral functioning in adults with chronic traumatic brain injury. Experimental brain research, 234(8), 2245–2252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-016-4630-8 |

Wrong intervention: Elliptical training |

|

Doble JE, Feinberg DL, Rosner MS, Rosner AJ. Identification of binocular vision dysfunction (vertical heterophoria) in traumatic brain injury patients and effects of individualized prismatic spectacle lenses in the treatment of postconcussive symptoms: a retrospective analysis. PM R. 2010 Apr;2(4):244-53. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.01.011. PMID: 20430325. |

Wrong study design: observational study |

|

Felipe, Lilian et al. "Virtual reality as a vestibular rehabilitation tool for athletes after concussion: a literature review." Advances in Rehabilitation, vol. 34, no. 2, 2020, pp. 42-48. doi:10.5114/areh.2020.94735. |

Wrong study design: no meta-analysis |

|

Gallaway M, Scheiman M, Mitchell GL. Vision Therapy for Post-Concussion Vision Disorders. Optom Vis Sci. 2017 Jan;94(1):68-73. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000935. PMID: 27505624. |

Wrong population: also acute TBI patients included |

|

Gottshall K, Gray N, Drake AI. A unique collaboration of female medical providers within the United States Armed Forces: rehabilitation of a marine with post-concussive vestibulopathy. Work. 2005;24(4):381-6. PMID: 15920313. |

Wrong study design: case study |

|

Hammerle M, Swan AA, Nelson JT, Treleaven JM. Retrospective Review: Effectiveness of Cervical Proprioception Retraining for Dizziness After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in a Military Population With Abnormal Cervical Proprioception. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2019 Jul;42(6):399-406. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2018.12.002. Epub 2019 Jul 27. PMID: 31362829. |

Wrong study design: retrospective review |

|

Hoffer ME, Gottshall KR, Moore R, Balough BJ, Wester D. Characterizing and treating dizziness after mild head trauma. Otol Neurotol. 2004 Mar;25(2):135-8. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200403000-00009. PMID: 15021772. |

Wrong study design: lack of comparison |

|

Hoffer ME, Schubert MC, Balaban CD. Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Traumatic Vestibulopathy and Postconcussive Dizziness. Neurol Clin. 2015 Aug;33(3):661-8, x. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.04.004. Epub 2015 Jun 12. PMID: 26231278. |

Wrong study design: prospective patient registry |

|

Hurtado JE, Heusel-Gillig L, Risk BB, Trofimova A, Abidi SA, Allen JW, Gore RK. Technology-enhanced visual desensitization home exercise program for post-concussive visually induced dizziness: a case series. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020 Sep 21:1-10. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2020.1815259. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32955968. |

Wrong study design: case series |

|

Kleffelgaard I, Soberg HL, Tamber AL, Bruusgaard KA, Pripp AH, Sandhaug M, Langhammer B. The effects of vestibular rehabilitation on dizziness and balance problems in patients after traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2019 Jan;33(1):74-84. doi: 10.1177/0269215518791274. Epub 2018 Jul 30. PMID: 30056743. |

Study was already included in the review from Rytter (2021) |

|

Murray DA, Meldrum D, Lennon O. Can vestibular rehabilitation exercises help patients with concussion? A systematic review of efficacy, prescription and progression patterns. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar;51(5):442-451. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096081. Epub 2016 Sep 21. PMID: 27655831. |

Wrong study design: no meta-analysis |

|

Murray NP, Hunfalvay M, Roberts CM, Tyagi A, Whittaker J, Noel C. Oculomotor Training for Poor Saccades Improves Functional Vision Scores and Neurobehavioral Symptoms. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl. 2021 Mar 31;3(2):100126. doi: 10.1016/j.arrct.2021.100126. PMID: 34179762; PMCID: PMC8212010. |

Wrong population: unclear description |

|

Nagib S, Linens SW. Vestibular Rehabilitation Therapy Improves Perceived Disability Associated With Dizziness Postconcussion. J Sport Rehabil. 2019 Sep 1;28(7):764-768. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2018-0021. PMID: 30040008. |

Review did not provide additional RCTs to the RCTs included in the review from Rytter (2021) |

|

Rowe FJ, Hanna K, Evans JR, Noonan CP, Garcia-Finana M, Dodridge CS, Howard C, Jarvis KA, MacDiarmid SL, Maan T, North L, Rodgers H. Interventions for eye movement disorders due to acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Mar 5;3(3):CD011290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011290.pub2. PMID: 29505103; PMCID: PMC6494416. |

Wrong study design: no meta-analysis |

|

Simpson-Jones ME, Hunt AW. Vision rehabilitation interventions following mild traumatic brain injury: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil. 2019 Sep;41(18):2206-2222. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1460407. Epub 2018 Apr 10. PMID: 29631511. |

Wrong study design: scoping review |

|

Søberg HL, Andelic N, Langhammer B, Tamber AL, Bruusgaard KA, Kleffelgaard I. Effect of vestibular rehabilitation on change in healicht THL-related quality of life in patients with dizziness and balance problems after traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2021 Apr 21;53(4):jrm00181. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2823. PMID: 33842981; PMCID: PMC8814830. |

Results of the intervention- and control group were not separately presented. |

|

Sveistrup H, McComas J, Thornton M, Marshall S, Finestone H, McCormick A, Babulic K, Mayhew A. Experimental studies of virtual reality-delivered compared to conventional exercise programs for rehabilitation. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2003 Jun;6(3):245-9. doi: 10.1089/109493103322011524. PMID: 12855079. |

Wrong population (frozen shoulder due to musculoskeletal pathology) |

|

Straudi S, Severini G, Sabbagh Charabati A, Pavarelli C, Gamberini G, Scotti A, Basaglia N. The effects of video game therapy on balance and attention in chronic ambulatory traumatic brain injury: an exploratory study. BMC Neurol. 2017 May 10;17(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0871-9. PMID: 28490322; PMCID: PMC5424286. |

Wrong control group: both received an intervention |

|

Thiagarajan P, Ciuffreda KJ. Effect of oculomotor rehabilitation on vergence responsivity in mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1223-40. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2012.12.0235. PMID: 24458963. |

Population too small (<10 per treatment arm) |

|

Thiagarajan P, Ciuffreda KJ. Effect of oculomotor rehabilitation on accommodative responsivity in mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(2):175-91. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2013.01.0027. PMID: 24933717. |

Wrong study design: observational study |

|

Thiagarajan P, Ciuffreda KJ, Capo-Aponte JE, Ludlam DP, Kapoor N. Oculomotor neurorehabilitation for reading in mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI): an integrative approach. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;34(1):129-46. doi: 10.3233/NRE-131025. PMID: 24284470. |

Population too small (<10 per treatment arm) |

|

Thiagarajan P, Ciuffreda KJ. Versional eye tracking in mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI): effects of oculomotor training (OMT). Brain Inj. 2014;28(7):930-43. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.888761. Epub 2014 Mar 21. PMID: 24826956. |

Population too small (<10 per treatment arm) |

|

Thornton M, Marshall S, McComas J, Finestone H, McCormick A, Sveistrup H. Benefits of activity and virtual reality based balance exercise programmes for adults with traumatic brain injury: perceptions of participants and their caregivers. Brain Inj. 2005 Nov;19(12):989-1000. doi: 10.1080/02699050500109944. PMID: 16263641. |

Wrong population (moderate-severe TBI) |

|

Watabe T, Suzuki H, Abe M, Sasaki S, Nagashima J, Kawate N. Systematic review of visual rehabilitation interventions for oculomotor deficits in patients with brain injury. Brain Inj. 2019;33(13-14):1592-1596. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1658225. Epub 2019 Aug 27. PMID: 31455098. |

Wrong study design: observational study |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 11-03-2024

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 11-03-2024

Algemene gegevens

In samenwerking met het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap.

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

De richtlijn is bestemd voor alle zorgverleners die betrokken zijn bij de diagnostiek, advisering of behandeling bij mensen met langer bestaande klachten (3 maanden) na licht traumatisch hoofd/hersenletsel, met name voor neurologen, revalidatieartsen en paramedici. De NHG-standaard Hoofdtrauma is leidend voor de huisartsen. Naast deze professionals is het van groot belang dat patiënten zelf ook weten waar ze in welk stadium met welke klachten terecht kunnen.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten aanhoudende klachten na licht THL.

Werkgroep

- drs. E.W.J. Agterhof, revalidatiearts, VRA

- drs. A. Baars, ergotherapeut, EN

- prof. dr. C.A.M van Bennekom, revalidatiearts/manager, VRA

- dr. N.L. Frankenmolen, i.o. tot klinisch neuropsycholoog, NIP

- drs. P.A.W. Frima-Verhoeven, neuroloog BreinPoli, NVN

- drs. E.A. Goedhart, bondsarts/manager sportgeneeskunde, VSG

- drs. R. Grond, revalidatiearts, VRA

- drs. A. Hansma, huisarts, NHG

- drs. E. Jagersma, revalidatiearts, VRA

- prof. dr. G. Kwakkel, hoogleraar Neurorevalidatie AUMC, KNGF

- drs. S.M. de Lange, bedrijfsarts, NVAB

- mr. M.A.C. Lindhout, Beleidsmedewerker patiëntenvereniging Hersenletstel.nl

- prof. dr. J. van der Naalt, neuroloog, NVN

- prof. dr. R.W.H.M. Ponds, klinisch neuropsycholoog, NIP

- drs. J.M. Schuurman, revalidatiearts, VRA

- prof. dr. J.M. Spikman, klinisch neuropsycholoog, hoogleraar klinische neuropsychologie, NIP

- dr. Melloney Wijenberg, GZ-psycholoog i.o., afdeling neurologie, Adelante, NIP

Met ondersteuning van:

- drs. F. Ham, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- drs. A.A. Lamberts, senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Bennekom, van |

Revalidatiearts/ manager R&D, revalidatiecentrum Heliomare te Wijk aan Zee |

Bijzonder hoogleraar revalidatie en arbeid, AUMC te Amsterdam, lid WHR (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Schuurman |

Revalidatiearts Stichting Klimmendaal Revalidatiespecialisten |

Lid WHR (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Jagersma |

Revalidatiearts, Basalt Den Haag |

Voorzitter Werkgroep Hersenletsel Revalidatie (WHR) van de VRA (onbetaalde nevenfunctie) |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Agterhof |

Revalidatiearts en medisch manager (0,6 en 0,2) bij de Hoogstraat Revalidatie |

Lid WHR (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Grond |

Revalidatiearts Basalt en HMC (0,4 fte en 0,4 fte). Gedetacheerd vanuit Basalt naar HMC |

Lid stafbestuur Basalt (onbetaald), Lid WHR (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Naalt |

Neuroloog Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Vanuit expertise in de neurotraumatologie lid van diverse regionale en landelijke commissies, allen onbezoldigd. |

Er is geen financier die belangen heeft bij de uitkomst van de richtlijn. Lopend onderzoek gefinancierd onderzoek door derden betreft:

T-Scemo4all gesubsidieerd door de Hersenstichting: Sociale cognitie en sociaal gedrag verbeteren bij diverse hersenaandoeningen (start 2020). Rol: Medeaanvrager UMCG, nationale multicenter studie.

BRAIN-ReADAPT studie naar het effect van veroudering bij NAH- patienten gesubsidieerd door Zon-MW (start 2021). Rol: PI UMCG, nationale multicenter studie. |

Geen. |

|

Frima-Verhoeven |

Neuroloog bij stichting BreinPoli |

Advies opdrachten bij het CCE, gemiddeld één per anderhalf jaar, betaald. |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Goedhart |

Bondarts/ Manager sportgeneeskunde KNVB |

Adviseur Stichting Hersenschudding - onbetaald |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Lindhout |

Beleidsmedewerker bij patiëntenvereniging Hersenletstel.nl |

Bestuurslid bij CVA-Kennisnetwerk, onbetaald |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Kwakkel |

* Hoogleraar Neurorevalidatie AUMC |

Geen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Hansma |

Huisarts |

Geen |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Lange, de |

AIOS bedrijfsgeneeskunde vierde jaar SGBO |

Geen |

Geen. |

|

|

Baars |

Ergotherapeut en mede-eigenaar Plan4 (ergotherapie praktijk in de 1e lijn) |

Voorzitter werkgroep ergotherapie en hersenletsel van Ergotherapie Nederland |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Wijenberg |

* Psycholoog, Afdeling Neurologie/ NAH, Adelante Revalidatiecentrum., Hoensbroek 0,8 fte * Docent, Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience (PFN), Maastrciht University, Maastricht, 0,2 fte |

Bestuurslid Sectie Revalidatie, Nederlands Instituut van Psychologen (NIP), onbetaald

Ik geef les over neuropsychologische onderwerpen vanuit mijn functie als psycholoog bij Adelante (Adelante ontvangt hier een compensatie voor). Dit verricht ik voor meerdere partijen w.o. RINO Zuid, Pro-Education, Maastiricht Univeristy |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Frankenmolen |

* GZ-psycholoog in opleiding tot klinisch neuropsycholoog, Klimmendaal Revalidatiespecialisten - 27 uur per week. * Senior onderzoeker, Klimmendaal Revalidatiespecialisten - 8 uur per week |

* Docent Praktijkresearch voor de KP-opleiding bij het RCSW, Nijmegen (betaald) * Gastdocent 'Pain and Psychology' voor de opleiding psychologie van de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen (betaald) * Lid werkgroep Onderzoek binnen de sectie Revalidatie van het NIP (onbetaald) |

Geen. |

Geen. |

|

Ponds |

* klinisch neuropsycholoog * Hoogleraar Medische Psychologie, VU * Hoofd afdeling Medische Psychologie, Amsterdam UMC |

* Voorzitter Nederlandse Vereniging voor Gezondheidszorgpsychologie (NVGzP), maandvergoeding * Bestuurslid TOP opleidingsplaatse, vacatiegeld * Bestuurslid PAON (post-acad. Opleiding klinisch neuropscycholoog), geen vergoeding * Bestuurslid P3NL, vacatiegeld |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Hersenstichting - PsyMate: e-healicht THL interventue vermoeidheid na hersenletsel – projectleider |

Geen. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een afgevaardigde van de patiëntvereniging Hersenletsel.nl te betrekken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie kop “Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten”). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en Stichting hersenschudding.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz