Jodiumhoudend CM en Diabetes Mellitus (DM)

Uitgangsvraag

Dient metformine te worden gestaakt voorafgaand aan intravasculaire jodiumhoudend contrastmiddel(CM)-toediening om metformine-geassocieerde lactaatacidose te voorkomen?

Aanbeveling

Continueer metformine bij elke patiënt met een eGFR ≥30 ml/min/1,73m2 bij wie het jodiumhoudend CM intravasculair wordt toegediend.

Staak metformine bij alle patiënten met een eGFR <30ml/min/1,73m2 bij wie intravasculair jodiumhoudend CM wordt toegediend zodra dit niveau van nierschade is gedetecteerd, en informeer de aanvrager van het onderzoek en voorschrijver van metformine.

Overwegingen

Metformin is the most frequently used oral glucose-lowering drug in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2). Reduced hepatic glucose production and increased insulin sensitivity are major mechanisms of its antihyperglycaemic effect (Lalau, 2015). Metformin inhibits the mitochondrial respiratory chain, impairing the main site of energy generation through aerobic metabolism. This results in a shift toward anaerobic metabolism with lactate as a by-product and less energy for gluconeogenesis. Compared to DM2 patients taking other glucose-lowering drugs, metformin users have reported somewhat higher serum lactate levels, but almost always within the normal range (Liu, 2009; Mongraw-Chaffin). However, in other studies no association between metformin use and serum lactate levels could be established (Lim, 2007; Connolly, 1996).

Lactic acidosis is an anion-gap metabolic acidosis defined by serum lactate levels greater than 5 mmol/l and pH less than 7.35 and is a feared complication of the use of metformin. Severe lactic acidosis causes multisystem organ disorder, particularly neurologic (stupor, coma, seizures) and cardiovascular (hypotension, ventricular fibrillation) dysfunction, and carries a >50% mortality risk. There is no evidence that in patients with a normal kidney function metformin use is associated with an increased risk of lactic acidosis (Inzucchi, 2014). In patients with impaired kidney function, metformin levels increase if the dose of metformin is not reduced, potentially increasing the risk of lactic acidosis. However, case-reports of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin indicate that lactic acidosis in most cases is unrelated to plasma metformin levels, challenging the concept of a causal relation between metformin use and the occurrence of lactic acidosis (Inzucchi, 2014). Zeller, 2016 included 89 patients not using metformin and 31 patients using metformin with an eGFR <60 ml/min. The mean eGFR in the metformin users was 48±10 ml/min. Acute kidney injury following the PCI procedure occurred in 41% of patients versus in 40% of non-metformin users. No case of lactic acidosis during hospital stay was observed. Lactic acidosis solely induced by metformin use is exceptionally rare. In patients who develop lactic acidosis, while using metformin, other comorbidities such as infection, acute kidney or liver failure or cardiac failure are almost always present. These comorbidities are supposed to play a central role in the aetiology of lactic acidosis in metformin users. Therefore, metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is a more appropriate term than the term metformin-induced lactic acidosis (Lalau, 2015).

Metformin is cleared by the kidney and eliminated unchanged in the urine. This drug may therefore accumulate in patients with impaired kidney function as can occur in response to administration of iodine-containing CM. Below which level of kidney function metformin should no longer be described is open to discussion.

Until very recently, the advice was not to prescribe metformin in patients with an eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Based on the available literature, a recent report in the JAMA suggests that metformin prescription at a reduced dose of maximal 1000 mg per day can be considered in patients with a CKD grade 3A (eGFR 45-59 ml/min/1.73m2), unless kidney function is expected to become unstable (Inzucchi, 2014). In accordance with this suggestion, the FDA Drug Safety Communication recently has revised warnings regarding the use of metformin in patients with reduced kidney function (FDA website). According to this guideline metformin is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2 and starting metformin in patients with an eGFR between 30 to 44 ml/min/1.73m2 is not recommended, but no longer contraindicated. In addition, it is advised to discontinue metformin at the time of or before an iodine-containing contrast imaging procedure in patients with an eGFR between 30 and 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The eGFR should be re-evaluated 48 hours after the imaging procedure and metformin can be restarted if renal function is stable.

The guideline released by the CMSC of the ESUR (version 9.0, 2014) for patients taking metformin is more liberal. Patients with an eGFR ≥ 45 ml/min/1.73 m2 receiving i.v. iodine-containing CM can continue to take metformin, whereas patients receiving i.v. or i.a. CM with an eGFR between 30 and 44 ml/min/1.73 m2 should stop metformin 48 h before iodine-containing CM administration and should only restart metformin 48 h after CM if renal function has not deteriorated. No advice is given for patients on metformin receiving i.a. contrast who have an eGFR 45 to 59 ml/min/1.73 m2. In agreement with the FDA guideline metformin is contraindicated in patients with an eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Goergen, 2010 has performed a systematic review of five guidelines and their underlying evidence concerning the risk of lactic acidosis after administration of iodine-containing CM. For their evaluation the authors used the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) instrument. The following five guidelines were assessed: The American College of Radiology (ACR), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR), the British Royal College of Radiologists (RCR), the Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR) and the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR).

Comparison of these guidelines with regard to recommendations about CM-administration revealed inconsistency between and lack of clarity within many of the guidelines.

The authors of this systematic review conclude:

- That there are inconsistencies between the recommendations of the five international guidelines about CM-administration in patients taking metformin.

- That these inconsistencies are in part caused by the low level or lack of evidence underlining guideline recommendations.

When translating their finding into implications for patient care, the conclusion of the authors is that there is no increased risk of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin who have a stable normal renal function, obviating the need to stop taking metformin before iodine-containing CM-administration.

In our systematic search and appraisal of the literature no studies could be found that provide any high quality evidence concerning our question about the continuation or discontinuation of metformin in relation to eGFR in patients undergoing radiologic examination with CM. As consequence only expert opinion-based recommendations can be given. It is the opinion of the workgroup that in patients with an eGFR ≥ 30 ml/min/1.73m2 the disadvantage of discontinuation of metformin with respect to the development of hyperglycaemia and administrative procedures does not weigh against its continuation as the chance of developing PC-AKI in these patients is negligibly low when the usual preventive measures like prehydration (see Hydration chapter 6) are taken.

Since the chance of kidney function deterioration with intravenous CM-administration is neglectably low, metformin (in appropriate dose) can be continued.

In situations where the chance of kidney deterioration is greater, it is the advice of the working group to discontinue metformin immediately before the procedure and to inform the physician who requested the procedure with intravascular contrast. According to the FDA guidelines metformin should always be discontinued in patients with an eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is a rare but severe complication. Metformin is cleared by the kidney. Therefore, increased circulating and tissue metformin levels may occur when kidney function is impaired. Of note, metformin itself is not nephrotoxic. Administration of iodine-containing contrast medium (CM) can temporarily impair kidney function, thereby increasing metformin levels and the risk of MALA. In addition, the risk of kidney function impairment in response to iodine-containing CM administration may be greater in patients with diabetes. Providing kidney function is normal or moderately impaired the risk of kidney function deterioration upon CM administration is extremely low, although the risk may vary between intravenous or intra-arterial routes of contrast administration.

This raises several questions:

- Is there evidence that below a certain level of kidney function, metformin should be discontinued before CM is administrated?

- Should a distinction be made between the routes of administration of CM, i.e. intravenously or intra-arterially?

- If metformin before CM administration is discontinued, when can it be restarted?

Conclusies

|

|

It is not clear whether cessation of metformin in patients undergoing intravascular contrast administration for radiological examination is effective for decreasing the risk of metformin-associated lactic acidosis and hyperglycaemia.

(Georgen, 2010) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

One systematic review (Georgen, 2010) was identified that examined the question whether metformin was related to lactic acidosis after administration of intravascular contrast medium for radiological research. Georgen (2010) performed a literature search from 1970 onward to March 2009. This systematic review included the evidence base of 5 frequently cited guidelines that consisted of RCTs, observational studies, case series and case reports. A total of 4 studies were deemed eligible and included in the review.

Results

Georgen, 2010 found a total of 4 studies, 2 summaries of published case-reports (McCartney, 1999; Stades, 2004), one case-series (Nawaz, 1998) and 1 case-report (Jain, 2008). The studies were deemed of insufficient quality to provide evidence to answer our research question due to their study design.

Quality of evidence

A quality of evidence could not be determined, since no original studies were found in this search, or in the included systematic review, that answered the research question appropriately.

Zoeken en selecteren

To answer our clinical question a systematic literature analysis was performed for the following research question:

Does discontinuation of metformin or reduction of metformin-dose in diabetic patients who are subjected to i.v. or i.a. contrast administration result in a lower risk of developing lactate acidosis and/or increase the risk of a serious hyperglycaemia?

P (Patient category): Diabetic patients on metformin with normal renal function or impaired renal function who are subjected to i.v. or i.a. contrast administration.

I (Intervention): Discontinuation of metformin or reduction of metformin-dose.

C (Comparison): Continuation of metformin.

O (Outcome): Metformin associated lactate acidosis and risk of serious hyperglycaemia.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered lactate acidosis and risk of serious hyperglycaemia as critical outcome measures for the decision making process. The working group defined serious hyperglycaemia as a blood glucose level >15mmol/l.

Search and select (method)

The data bases Medline (OVID), Embase and the Cochrane Library were searched from January 2000 up to April 2017 using relevant search terms for systematic reviews (SRs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (OBS). The literature search procured 211 hits.

Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Adult patients who underwent radiological examination using contrast media (including radiological examination during percutaneous angiography).

- Patients with impaired kidney function, at least eGFR <60 ml/min/1,73m2.

- Hydration types: hydration with NaCl, hydration with bicarbonate, oral hydration, pre-hydration, pre- and posthydration.

- At least one of the outcome measures was described: metformin associated lactate acidosis, risk of serious hyperglycaemia.

Based on title and abstract a total of 62 studies were selected. After examination of full text a total of 60 studies were excluded and 1 study definitely included in the literature summary. This was a systematic review of guidelines and original articles (Georgen, 2010) that examined our research question.

Results

Studies were included in the literature analysis, the most important study characteristics and results were included in the evidence tables. The evidence tables and assessment of individual study quality are included

Referenties

- Connolly V, Kesson CM. Metformin treatment in NIDDM patients with mild renal impairment. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(848):352-4.

- Contrast Media Safety Committee ESUR. Guidelines on Contrast Media, v9, 2014. European Society of Urogenital Radiology.2014. Available at: www.esur-cm.org.

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises warnings regarding use of the diabetes medicine metformin in patients with reduced kidney function. Dated 8 april 2016. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM494140.pdf

- Goergen SK, Rumbold G, Compton G, et al. Systematic review of current guidelines, and their evidence base, on risk of lactic acidosis after administration of contrast medium for patients receiving metformin. Radiology. 2010;254(1):261-9.

- Graham GG, Punt J, Arora M, et al., Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(2):81-98.

- Inzucchi SE, Lipska KJ, Mayo H, et al. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2668-75.

- Jain V, Sharma D, Prabhakar H, et al. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis following contrast media-induced nephrotoxicity. Eur J Anesthes. 2008;25(2):166-7.

- Lalau JD, Arnouts P, Sharif A, et al. Metformin and other antidiabetic agents in renal failure patients. Kidney Int. 2015;87(2):308-22.

- Lim VC, Sum CF, Chan ES, et al. Lactate levels in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on metformin and its association with dose of metformin and renal function. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(11):1829-33.

- Liu F, Lu JX, Tang JL, et al. Relationship of plasma creatinine and lactic acid in type 2 diabetic patients without renal dysfunction. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122(21):2547-53.

- McCartney MM, Gilbert FJ, Murchison LE, et al. Metformin and contrast mediaa dangerous combination? Clin Radiol. 1999;54(1):29-33.

- Mongraw-Chaffin ML, Matsushita K, Brancati FL, et al., Diabetes medication use and blood lactate level among participants with type 2 diabetes: the atherosclerosis risk in communities carotid MRI study. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51237.

- Nawaz S, Cleveland T, Gaines PA, et al. Clinical risk associated with contrast angiography in metformin treated patients: a clinical review. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(5):342-4.

- Stades AM, Heikens JT, Erkelens DW, et al. Metformin and lactic acidosis: cause or coincidence? A review of case reports. J Intern Med. 2004;255(2):179-87.

- Zeller M, Labalette-Bart M, Juliard JM, et al. Metformin and contrast-induced acute kidney injury in diabetic patients treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: A multicenter study. In J Cardiol 2016;220:137-142.

Evidence tabellen

Table: Exclusion of article after examination of full tekst.

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aronson, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Baerlocher, 2013 |

Review, not systematic |

|

Blickle, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Bloomgarten, 1996 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Boscheri, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Chan, 1999 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Chong, 2004 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Cicero, 2012 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Dawson, 2002 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Dichtwald, 2011 |

Case series, no control group |

|

Douros, 2015 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Elder, 2003 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Erley, 2006 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Goergen, 2010_1 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Gomez-Herrerp, 2013 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Gupta, 2002 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Hammond |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Heikkinen, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Heupler, 1998 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Hoste, 2013 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Jain, 2008 |

Included in systematic review Goergen, 2010 |

|

Jones, 2003 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Kdoqi, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Khurana, 2010_1 |

Review, not systematic |

|

Khurana, 2010_2 |

Letter to editor |

|

Klepser, 1997 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Koc, 2013 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Lalau, 2001 |

Systematic review, however more recent systematic (Georgen, 2010) present and included in literature summary |

|

Landewe-Cleuren, 2000 |

Review, not systematic |

|

Leow, 2015 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Longeran, 2008 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

McCartney, 1999 |

Systematic review, however more recent systematic (Georgen, 2010) present and included in literature summary |

|

Millican, 2004 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Morcos, 2001 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Morcos, 2005 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Nawaz, 1998 |

Included in systematic review Goergen, 2010 |

|

Nolan, 1997 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Parra, 2004 |

No control group. |

|

Pond, 1996 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Quasny, 1997 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Radwan, 2011 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Rakovac, 2005 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Rasuli, 1998_1 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Rasuli, 1998_2 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Safadi, 1996 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Sayer, 2006 |

Letter to the editor |

|

Schweiger, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Senior, 2012 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Setter, 2003 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Stacul, 2006 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Stacul, 2011 |

Guideline tekst, not an original article |

|

Thompson, 2000 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Thomsen, 2003 |

Guideline tekst, not an original article |

|

Thomsen, 2010 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Thomson 2010 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Tonolini, 2012 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Tzakias, 2013 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Tzakias, 2014 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Van Dijk, 2008 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

|

Widmark, 2007 |

Does not meet selection criteria |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Goergen, 2010 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Goergen, 2010

[individual study characteristics deduced from [1st author, year of publication]

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of [RCTs / cohort / case-control studies]

Literature search up to March 2009

A: Nawaz, 1998 B: MacCartney, 1999 C: Stades, 2004 D: Jain, 2008

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over], cohort [prospective / retrospective], case-series, case-control A: case-series B: summary of case-reports C: summary of case-reports D: case report

Setting and Country: Australia, in- and outpatiennts

Source of funding: Not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: 1) English language publication 2) administration of iodinated contrast medium in adult patients who were tacing metformin 3) lactic acidosis was outcome measure

Exclusion criteria SR: 1) studies in children (<18 years) 2) procedures in which administration of contrast medium was not used 3) lactic acidosis was not one of the outcomes assessed 4) publications that were letters, narratives, editorials, reviews based on only expert opinion, draft reports

4 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: 33, not reported B: 18, not reported C: 47, not reported D: 1, not reported

Sex: A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported

Impaired renal function: A; 4/33 (12%) B:16/18 (89%) (unclear if this is correct number) C: not reported D: 0/1 (0%)

Groups comparable at baseline? Not applicable (no control group) |

Describe intervention:

A: metformin and undergoing angiography B: patients who had metformin-associated lactic acidosis after use of intravenous iodinated contrast medium C: patients who had metformin-associated lactic acidosis, 26% of them received contrast medium prior D: metformin-associated lactic acidosis,

|

Describe control:

A: not applicable B: not applicable C: not applicable D: not applicable

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: not reported B: not reported C: not reported D: not reported

|

Outcome measure-1 Defined as presence of metformin associated lactic acidosis (MALA), or relation between MALA and iodinated contrast medium administration

Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95% CI]: A: 4 patients died (2 attributed to acute renal failure and lactic acidosis), in 29 patients with normal renal function no change was observed after procedure B: in 16-17 out of 18 cases renal dysfunction or other contra-indication was present C: 25% of cases had intravascular contrast medium administered D: metformin-associated lactic acidosis, developed in patient with normal renal function

Pooled effect (random effects model / fixed effects model): No pooling was possible due to heterogeneity of included studies

|

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion: It is not clear whether cessation of metformin in patient undergoing intravascular contrast administration for radiological examination is effective for decreasing the risk of lactic acidosis and hyperglycemia.

Level of evidence: GRADE: All included studies had a very low quality of evidence (summaries of case-reports, case-series, case-report) -no studies with control group

For study C (stades, 2004) contrast medium was administered in 26% of the cases. |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-11-2017

Laatst geautoriseerd : 01-11-2017

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-12-2023

Validity

The board of the Radiological Society of the Netherlands will determine at the latest in 2023 if this guideline (per module) is still valid and applicable. If necessary, a new working group will be formed to revise the guideline. The validity of a guideline can be shorter than 5 years, if new scientific or healthcare structure developments arise, that could be seen as a reason to commence revisions. The Radiological Society of the Netherlands is considered the keeper of this guideline and thus primarily responsible for the actuality of the guideline. The other scientific societies that have participated in the guideline development share the responsibility to inform the primarily responsible scientific society about relevant developments in their field.

Initiative

Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Authorization

The guideline is submitted for authorization to:

- Association of Surgeons of the Netherlands

- Dutch Association of Urology

- Dutch Federation of Nephrology

- Dutch Society Medical Imaging and Radiotherapy

- Dutch Society of Intensive Care

- Netherlands Association of Internal Medici

- Netherlands Society for Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine

- Netherlands Society of Cardiology

- Netherlands Society of Emergency Physicians

- Radiological Society of the Netherlands

Algemene gegevens

General Information

The guideline development was assisted by the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (https://www.kennisinstituut.nl) and was financed by the Quality Funds for Medical Specialists (Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten: SKMS).

Doel en doelgroep

Goal of the current guideline

The aim of the Part 1 of Safe Use of Iodine-containing Contrast Media guidelines is to critically review the present recent evidence with the above trend in mind, and try to formulate new practical guidelines for all hospital physicians to provide the safe use of contrast media in diagnostic and interventional studies. The ultimate goal of this guideline is to increase the quality of care, by providing efficient and expedient healthcare to the specific patient populations that may benefit from this healthcare and simultaneously guard patients from ineffective care. Furthermore, such a guideline should ideally be able to save money and reduce day-hospital waiting lists.

Users of this guideline

This guideline is intended for all hospital physicians that request or perform diagnostic or interventional radiologic or cardiologic studies for their patients in which CM are involved.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Working group members

A multidisciplinary working group was formed for the development of the guideline in 2014. The working group consisted of representatives from all relevant medical specialization fields that are involved with intravascular contrast administration.

All working group members have been officially delegated for participation in the working group by their scientific societies. The working group has developed a guideline in the period from October 2014 until July 2017.

The working group is responsible for the complete text of this guideline.

Working group

Cobbaert C., clinical chemist, Leiden University Medical Centre (member of advisory board from September 2015)

Danse P., interventional cardiologist, Rijnstate Hospital, Arnhem

Dekker H.M., radiologist, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen

Geenen R.W.F., radiologist, Noordwest Ziekenhuisgroep (NWZ), Alkmaar/Den Helder

Hoogeveen E.K., nephrologist, Jeroen Bosch Hospital, ‘s-Hertogenbosch

Kooiman J., research physician, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden

Oudemans - van Straaten H.M., internist-intensive care specialist, Free University Medical Centre, Amsterdam

Pels Rijcken T.H., interventional radiologist, Tergooi, Hilversum

Sijpkens Y.W.J., nephrologist, Haaglanden Medical Centre, The Hague

Vainas T., vascular surgeon, University Medical Centre Groningen (until September 2015)

van den Meiracker A.H., internist-vascular medicine, Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam

van der Molen A.J., radiologist, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden (chairman)

Wikkeling O.R.M., vascular surgeon, Heelkunde Friesland Groep, location: Nij Smellinghe Hospital, Drachten (from September 2015)

Advisory board

Demir A.Y., clinical chemist, Meander Medical Center, Amersfoort, (member of working group until September 2015)

Hubbers R., patient representative, Dutch Kidney Patient Association

Mazel J., urologist, Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem

Moos S., resident in Radiology, HAGA Hospital, The Hague

Prantl K., Coordinator Quality & Research, Dutch Kidney Patient Association

van den Wijngaard J., resident in Clinical Chemistry, Leiden University Medical Center

Methodological support

Boschman J., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from May 2017)

Burger K., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (until March 2015)

Harmsen W., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from May 2017)

Mostovaya I.M., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists

Persoon S., advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (March 2016 – September 2016)

van Enst A., senior advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists (from January 2017)

Belangenverklaringen

Conflicts of interest

The working group members have provided written statements about (financially supported) relations with commercial companies, organisations or institutions that are related to the subject matter of the guideline. Furthermore, inquiries have been made regarding personal financial interests, interests due to personal relationships, interests related to reputation management, interest related to externally financed research and interests related to knowledge valorisation. The statements on conflict of interest can be requested at the administrative office of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists and are summarised below.

|

Member |

Function |

Other offices |

Personal financial interests |

Personal relationships |

Reputation management |

Externally financed research |

Knowledge-valorisation |

Other potential conflicts of interest |

Signed |

|

Workgroup |

|||||||||

|

Burger |

Advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Cobbaert |

Member, physician clinical chemistry |

Head of clinical chemistry department in Leiden LUMC. Tutor for post-academic training of clinical chemists, coordinator/host for the Leiden region Member of several working groups within the Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and member of several international working groups for clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

Member of several working groups within the Dutch Society for Clinical Chemistry and member of several international working groups for clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Danse |

Member, cardiologist |

Board member committee of Quality, Dutch society for Cardiology (unpaid) Board member Conference committee DRES (unpaid) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Dekker |

Member, radiologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Geenen |

Member, radiologist |

Member Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (unpaid, meetings are partially funded by CM industry))) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Has been a public speaker during symposia organised by GE Healthcare about contrast agents (most recently in June 2014) |

Yes |

|

Hoogeveen |

Member, nephrologist |

Member of Guideline Committee of Dutch Federation of Nephrology |

None |

None |

Member of Guideline Committee of Dutch Society for Nephrology |

Grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation to study effect of fish oil on kidney function in post-MI patients |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Kooiman |

Member, research physician |

Resident in department of gynaecology & obstetrics |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Mostovaya |

Advisor, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Oudemans – van Straaten |

Member, intensive care medical specialist Professor Intensive Care |

none |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Pels Rijcken |

Member, interventional radiologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Sijpkens |

Member, nephrologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Vainas |

Member, vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Van den Meiracker |

Member, internist vascular medicine |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Van der Molen |

Chairman, radiologist |

Member Contrast Media Safety Committee of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (unpaid,CMSC meetings are partially funded by CM industry)) |

None |

None |

Secretary section of Abdominal Radiology; Radiological Society of the Netherlands (until spring of 2015) |

None |

None |

Receives Royalties for books: Contrast Media Safety, ESUR guidelines, 3rd ed. Springer, 2015 Received speaker fees for lectures on CM safety by GE Healthcare, Guerbet, Bayer Healthcare and Bracco Imaging (2015-2016) |

Yes |

|

Wikkeling |

Member, vascular surgeon |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Advisory Board |

|||||||||

|

Demir |

Member, physician clinical chemistry |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Hubbers |

Member, patient’s representative, Dutch Society of Kidney Patients |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Mazel |

Member, urologist |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Prantl |

Member, policy maker, Dutch Society of Kidney Patients |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

|

Van den Wijngaard |

Member, resident clinical chemistry |

Reviewer for several journals (such as American Journal of Physiology) |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

None |

Yes |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Patients’ perspective was represented, firstly by membership and involvement in the advisory board of a policy maker and a patients’ representative from the Dutch Kidney Patient Association. Furthermore, an online survey was organized by the Dutch Kidney Patient Association about the subject matter of the guideline. A summary of the results of this survey has been discussed during a working group meeting at the beginning of the guideline development process. Subjects that were deemed relevant by patients were included in the outline of the guideline. The concept guideline has also been submitted for feedback during the comment process to the Dutch Patient and Consumer Federation, who have reported their feedback through the Dutch Kidney Patient Association.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In the different phases of guideline development, the implementation of the guideline and the practical enforceability of the guideline were taken into account. The factors that could facilitate or hinder the introduction of the guideline in clinical practice have been explicitly considered. The implementation plan can be found with the Related Products. Furthermore, quality indicators were developed to enhance the implementation of the guideline. The indicators can also be found with the Related Products.

Werkwijze

AGREE

This guideline has been developed conforming to the requirements of the report of Guidelines for Medical Specialists 2.0; the advisory committee of the Quality Counsel. This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreetrust.org), a broadly accepted instrument in the international community and on the national quality standards for guidelines: “Guidelines for guidelines” (www.zorginstituutnederland.nl).

Identification of subject matter

During the initial phase of the guideline development, the chairman, working group and the advisor inventory the relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, an Invitational Conference was organized, where additional relevant subjects were suggested by the Dutch Kidney Patient Association, Dutch Society for Emergency Physicians, and Dutch Society for Urology. A report of this meeting can be found in Related Products.

Clinical questions and outcomes

During the initial phase of guideline development, the chairman, working group and advisor identified relevant subject matter for the guideline. Furthermore, input was acquired for the outline of the guideline during an Invitational Conference. The working group then formulated definitive clinical questions and defined relevant outcome measures (both beneficial land harmful effects). The working group rated the outcome measures as critical, important and not important. Furthermore, where applicable, the working group defined relevant clinical differences.

Strategy for search and selection of literature

For the separate clinical questions, specific search terms were formulated and published scientific articles were sought after in (several) electronic databases. Furthermore, studies were looked for by cross-referencing other included studies. The studies with potentially the highest quality of research were looked for first. The working group members selected literature in pairs (independently of each other) based on title and abstract. A second selection was performed based on full text. The databases search terms and selection criteria are described in the modules containing the clinical questions.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were systematically assessed, based on methodological quality criteria that were determined prior to the search, so that risk of bias could be estimated. This is described in the “risk of bias” tables.

Summary of literature

The relevant research findings of all selected articles are shown in evidence tables. The most important findings in literature are described in literature summaries. When there were enough similarities between studies, the study data were pooled.

Grading the strength of scientific evidence

A) For intervention questions

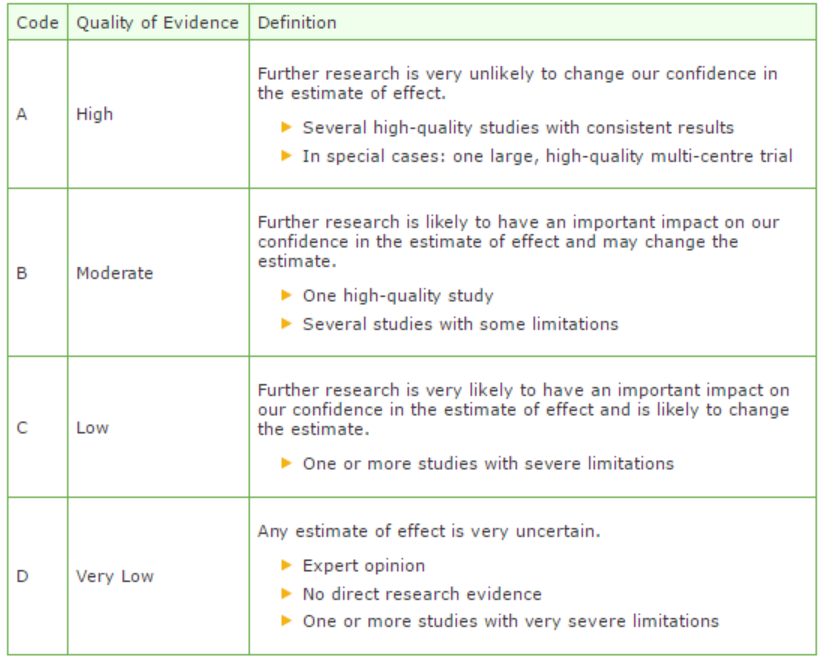

The strength of the conclusions of the scientific publications was determined using the GRADE-method. GRADE stands for Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) (Atkins, 2004).

GRADE defines four gradations for the quality of scientific evidence: high, moderate, low or very low. These gradations provide information about the amount of certainty about the literature conclusions. (http://www.guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook/).

B) For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the GRADE-methodology cannot (yet) be applied. The quality of evidence of the conclusion is determined by the EBRO method (van Everdingen, 2004)

Formulating conclusion

For diagnostic, etiological, prognostic or adverse effect questions, the evidence was summarized in one or more conclusions, and the level of the most relevant evidence was reported. For intervention questions, the conclusion was drawn based on the body of evidence (not one or several articles). The working groups weighed the beneficial and harmful effects of the intervention.

Considerations

Aspects such as expertise of working group members, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities, and organization of healthcare aspects are important to consider when formulating a recommendation. These aspects were discussed in the paragraph Considerations.

Formulating recommendations

The recommendations answer the clinical question and were based on the available scientific evidence and the most relevant considerations.

Constraints (organization of healthcare)

During the development of the outline of the guideline and the rest of the guideline development process, the organization of healthcare was explicitly taken into account. Constraints that were relevant for certain clinical questions were discussed in the Consideration paragraphs of those clinical questions. The comprehensive and additional aspects of the organization of healthcare were discussed in a separate chapter.

Development of quality indicators

Internal (meant for use by scientific society or its members) quality indicators are developed simultaneously with the guideline. Furthermore, existing indicators on this subject were critically appraised; and the working group produces an advice about such indicators. Additional information on the development of quality indicators is available by contacting the Knowledge Institute for Medical Specialists. (secretariaat@kennisinstituut.nl).

Knowledge Gaps

During the development of the guideline, a systematic literature search was performed the results of which help to answer the clinical questions. For each clinical question the working group determined if additional scientific research on this subject was desirable. An overview of recommendations for further research is available in the appendix Knowledge Gaps.

Comment- and authorisation phase

The concept guideline was subjected to commentaries by the involved scientific societies. The commentaries were collected and discussed with the working group. The feedback was used to improve the guideline; afterwards the working group made the guideline definitive. The final version of the guideline was offered for authorization to the involved scientific societies, and was authorized.

References

Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, et al. GRADE Working Group. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004 Dec 22;4(1):38.

Van Everdingen JJE, Burgers JS, Assendelft WJJ, et al. Evidence-based richtlijnontwikkeling. Bohn Stafleu van Loghum. Houten, 2004

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.