Chopart letsel

Uitgangsvraag

Welke behandeling reduceert de meest voorkomende korte en lange termijn gevolgen van Chopart letsels?

Aanbeveling

Behandel patiënten met een open fractuur en/of persisterende luxatiestand van het Chopart gewricht operatief.

Overweeg bij patiënten met een incongruent gewricht (fractuur-dislocatie ≥ 2mm) of instabiliteit in het talonaviculaire (TN) en/of calcaneocuboidale (CC) gewricht een operatieve behandeling, met als doel congruentie en stabiliteit in het Chopart gewricht.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd naar de beste behandeling van Chopart letsels, hierbij werd operatieve behandeling vergeleken met conservatieve behandeling. Er zijn drie observationele studies gevonden waarin deze twee typen behandeling in een directe vergelijking werden geanalyseerd (Coulibaly, 2015; van Dorp, 2010; Richter, 2004). Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten functionele uitkomst, artrose, noodzaak voor artrodese en complicaties werd slechts bewijs met een zeer lage bewijskracht gevonden, waardoor er veel onzekerheid bestaat over het gevonden effect. Ook voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten duur van immobilisatie en tekenen van chronische instabiliteit werd slechts bewijs met een zeer lage bewijskracht gevonden.

Er zijn geen gerandomiseerde trials gevonden waarin operatieve behandeling vergeleken werd met non-operatieve behandeling. Al het bewijs is afkomstig van observationeel retrospectief onderzoek. Dit heeft van nature een lage bewijskracht. Er was één studie waarin slechts negen patiënten waren geïncludeerd, een dergelijke studiepopulatie is te klein om een betrouwbare conclusie te trekken. Ook was voor een aantal uitkomstmaten een laag aantal cases, wat resulteert in brede 95% betrouwbaarheidsintervallen. In de drie geïncludeerde studies werd niet adequaat gecorrigeerd voor de belangrijkste confounders. Hierdoor is het onduidelijk of de gevonden effecten veroorzaakt worden door de verschillende interventies die de operatieve en non-operatieve groep zijn ondergaan, of dat het verschil veroorzaakt wordt door een andere factor (bijvoorbeeld verschillen in de patiëntkarakteristieken van beide studiearmen). Uit de studie van Coulibaly (2015) blijkt dat in de conservatieve groep het aantal patiënten met een ernstig letsel aanzienlijk minder is, dan het aantal patiënten met ernstig letsel in de operatieve groep. Het risico op selectie bias is bij alle drie de studies groot omdat het type letsel en ernst van het letsel bepalend was voor het type behandeling die de patiënt onderging. Dit maakt het lastig om op basis van de gevonden literatuur conclusies te trekken over het effect van de behandeling. De overwegingen zijn dan voornamelijk geschreven vanuit praktijkervaring en expert opinion.

Hoewel er op basis van de gevonden literatuur geen conclusies getrokken kunnen worden over de aangewezen behandelstrategie, laat de literatuur wel zien dat in algemene zin geldt dat bij de behandeling (operatief én non-operatief) van Chopart letsel de kans op volledig herstel 68% tot 79% is. Het risico op artrose is 43% tot 85%, het risico op persisterende instabiliteit is 2% tot 4%, en het risico op complicaties bij de wondgenezing 4% tot 7%.

Open fracturen en luxaties van het Chopart gewricht dienen geopereerd te worden. Hiervoor wordt vaak een externe fixateur gebruikt. Voorheen werd dit letsel dan ook uitbehandeld in de externe fixateur, waar tegenwoordig interne fixatie met plaat-schroeven en K-draden veelvuldig de volgende stap in stabilisatie is.

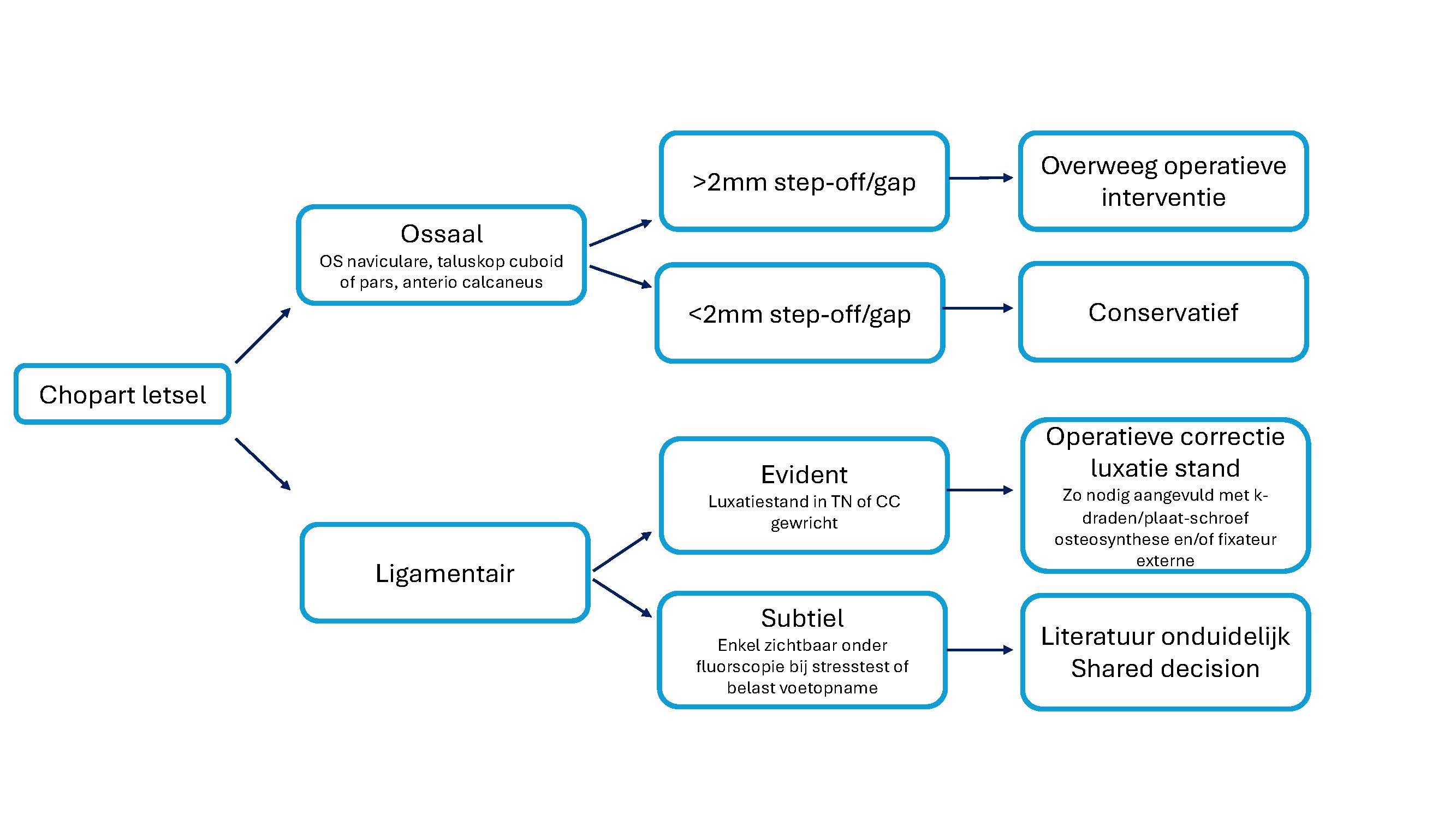

Het ontstaan van een letsel van het Chopart gewricht door een trauma kan tot een gecompliceerd beloop leiden met verminderde functie van de ledemaat, toegenomen kans op artrose of collaps van de stand van de voet-enkel. Fracturen intra-articulair, in het bereik van het Chopart gewricht, (os naviculare, taluskop, cuboid of pars anterior calcaneus) die tot discongruentie van het gewricht leiden (>2 mm step-off of gap intra-articulair) of tot een afwijkende (stress-belaste) alignment van de voet, verhogen het risico op een dergelijk gecompliceerd beloop. Hierbij is de verwachting dat operatieve correctie van de gewrichtsdiscongruentie/malalignment en stabilisatie van de gewrichten na een dergelijk letsel het risico op deze late gevolgen kan verminderen (zie Figuur 1).

Onduidelijk is of bij patiënten met intra-articulaire fracturen in het Chopart bereik zonder discongruentie (<2 mm step-off of gap) of gewrichten die alleen bij stresstesten een afwijkende alignment hebben ook beter operatief behandeld kunnen worden of dat gipsimmobilisatie een gelijkwaardige optie is. Hierover bestaat een kennislacune

Figuur 1: behandelopties Chopart letsel. TN = talonaviculaire; CC = calcaneocuboidale; mm = milimeter.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor de patiënt zijn de belangrijkste doelen van de behandeling een stabiele, functionele en pijnloze voet in het dagelijks leven. Na eerste opvang en initiële behandeling (behandeling evidente luxatiestand gewrichten en behandeling open fracturen), is het wenselijk de behandelopties te bespreken met de betreffende voor- en nadelen van de behandelingen en onzekerheid in de verwachte uitkomst. Hierbij dienen in ieder geval complicaties van operatie, complicaties van non-operatieve zorg en verwachting ten aanzien van functionele uitkomsten besproken te worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er is geen data over de kosteneffectiviteit van beide behandelopties. Naar verwachting brengt operatief ingrijpen hogere kosten met zich mee. Secundaire ingrijpen kunnen bij beide behandelingen nodig zijn, het is onduidelijk hoe vaak secundaire ingrepen nodig zijn. Gezien het doel om de patiënt zo goed mogelijk te behandelen, spelen kosten doorgaans geen rol bij deze keuze om een patiënt operatief dan wel niet-operatief te behandelen. Beide behandelopties vallen onder de verzekerde zorg.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Expertise over- en exposure aan dit letsel is in de meeste ziekenhuizen beperkt. Met name een beperking in de ‘index of suspicion’ zal ook meespelen met de problemen met detectie van instabiliteit bij een letsel in het bereik van een Chopart letsel. Ook bij evidente instabiliteit of complexe fracturen in de ossale structuren rondom het Chopart gewricht is de expertise beperkt door de lage frequentie van voorkomen. De expertise op traumatologisch gebied is beperkt, zeker waar het chirurgische interventies betreft, dit is mogelijk een belemmerende factor. Naar verwachting zijn er geen andere belemmerende factoren (bijv. aanwezigheid van apparatuur).

Acute zorg is voor eenieder toegankelijk ongeacht niveau van gezondsheidsvaardigheden, sociale klasse, opleidingsniveau, inkomen of migratie-achtergrond.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er is geen bewijs dat operatieve behandeling bij patiënten met een Chopart letsel betere uitkomsten geeft dan conservatieve behandeling. In de geselecteerde retrospectieve studies werden door selectie bias patiënten met een mild letsel conservatief behandeld en patiënten met een ernstig letsel operatief zonder dat er prospectieve vergelijkende studies beschikbaar zijn. De ernst van het letsel werd ook als negatief prognostische factor gevonden. De werkgroep is het, gezien deze resultaten, erover eens dat open fracturen en persisterende luxatiestand in het Chopart gewricht operatief behandeld dienen te worden. Aangezien fracturen die in het bereik van het Chopart gewricht intra-articulair verlopen (os naviculare, taluskop, cuboid of pars anterior calcaneus) tot discongruentie van het gewricht kunnen leiden of tekenen van instabiliteit kunnen hebben, is de werkgroep van mening dat deze groep ook baat kan hebben bij operatieve behandeling om de mogelijke late gevolgen te minimaliseren. Onduidelijk is of intra-articulaire fracturen in het Chopart bereik zonder discongruentie of gewrichten die bij stresstesten een goede alignment behouden ook beter operatief behandeld kunnen worden of dat gipsimmobilisatie dan een gelijkwaardige optie is. Deze keuze zou samen met de patiënt gemaakt kunnen worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het Chopart gewricht is een gewrichtscomplex, essentieel voor de loopgang van een mens. Zowel mobiliteit als stabiliteit zijn noodzakelijk voor een goed functioneren hiervan doordat er een translatie van de kracht en beweging van de achtervoet naar de voorvoet ontstaat. Een traumatisch Chopart letsel ontstaat doordat een externe kracht op het talo-naviculare en/of calcaneo-cuboidale gewricht inwerkt, al dan niet met fracturen in het bereik van deze gewrichten, al dan niet met instabiliteit. De huidige behandeling van Chopart letsels richt zich op stabilisatie van de gewrichten in een goede alignment en/of fixatie van fracturen met congruente gewrichtsoppervlakken. Er is een grote variatie aan behandelingen mogelijk van gipsimmobilisatie, open repositie en interne fixatie tot artrodese van het Chopart gewricht. Onduidelijkheid over de uitkomsten van de individuele behandeling maakt dat er ook een grote praktijkvariatie in behandelkeuzes aanwezig is.

Conclusies

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of operative treatment on the outcomes functional outcome, arthritis, need for arthrodesis, adverse events duration of immobilization and signs of chronic instability when compared with non-operative treatment in patients with Chopart injuries.

Source: van Dorp, 2010; Richter, 2004; Coulibaly, 2015 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Coulibaly 2015 compared the results of operative treatment and non-operative treatment in navicular fractures, in a retrospective cohort. Patients presented at a level-I trauma centre in the USA with navicular fractures were included (n = 110). Inclusion criteria were radiographically diagnosed navicular fractures, skeletal maturity, and initial treatment at the study institution. Exclusion criteria were stress fractures, unavailable radiographic images at injury and at follow-up and follow-up of less than three months. In total, 41/90 (45.6%) patients received operative treatment and 49/90 (54.4%) non-operative treatment. The specific techniques that were used are presented in table 1. Five fellowship trained orthopaedic surgeons performed all operative procedures. Techniques of fixation and supplemental support varied depending on fracture pattern and surgeon preference. It was stated that operative treatment was related to increasing severity of fracture. Outcomes were assessed at final follow-up at 52 weeks. It was stated that 48 patients were lost to follow-up and 62 patients (with 64 fractures) were included in the full analysis (operative treatment group: n = 35; non-operative treatment group: n = 29). However, data on treatment outcomes was available for 90 patients. Outcomes included functional outcomes (pain and level of activity), secondary osteoarthritis, surgical site infection, non-union, avascular necrosis and time to weight bearing. There was no correction for confounding factors in the analysis, which is considered a limitation of this study.

Van Dorp 2010 retrospectively studied the outcome and morbidity in patients with Chopart joint injuries. All consecutive patients with a joint-dislocation or fracture dislocation of the Chopart joint treated at a Dutch level-2 trauma were included in the analysis (n = 9). Lisfranc fracture dislocations and isolated midfoot fractures were excluded from the analyses. Three patients received operative treatment and six patients were treated non-operatively. The specific techniques that were used are presented in Table 1. The patients being treated operatively on average were younger (mean ± SD: 19 ± 3.6) than the patients receiving non-operative treatment (mean ± SD: 53 ± 23). After a minimum of six months follow-up outcomes were assessed, average follow-up was 31.3 ± 19.2 months. Two patients were excluded because their follow-up was less than six months. Outcomes included the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society Midfoot Score (AOFAS), measuring pain, function and alignment. Additional outcomes were presence or absence of pain and ability to perform work or hobby. There was no correction for confounding factors in the analysis, which is considered a limitation of this study.

Richter 2004 performed a retrospective study on the injury cause, treatment and long-term results of patients with Chopart joint dislocations or fracture dislocations. Patients presented at a level-I Trauma Center in Germany with Chopart joint dislocations or Chopart joint fracture-dislocations or combined Chopart-Lisfranc joint fracture-dislocations were included in the study (n = 100). Mean age of the study population was 32 years (range 17-85 years), 68% of the patients were male. Chopart joint dislocations were treated non-operatively with closed reduction without internal fixation. All the patients undergoing closed reduction without internal fixation had pure Chopart joint dislocations, see Table 1. Indications for non-operative treatment were sufficient closed anatomic reduction, sufficient stability after reduction in anatomic position and contra-indications for operative treatment. Patients with Chopart fracture-dislocations or Chopart-Lisfranc fracture dislocations received internal fixation, with open or closed reduction, see Table 1. Demographic data was not presented per treatment group. As a consequence, it is not possible to determine whether the two treatment groups were comparable, which is a limitation of this study. Outcomes were assessed after minimal two years of follow-up. The mean follow-up duration was 9 years (range 2-25 years). Outcome data was available for 58 patients (59 Chopart joint dislocations), 51 were treated operatively and 8 were treated non-operatively. The AOFAS-score was included as an outcome. There was no correction for confounding factors in the analysis, which is considered a limitation of this study.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the studies included in the analysis.

|

|

Operative treatment |

Non Operative Treatment |

|

Coulibaly (2015)

(level 1 trauma center, navicular fractures) |

Open reduction with internal fixation (ORIF; n = 41) Fixation with 2.0 or 2.7 mm spanning plates or screws, if necessary with external fixator. |

Toe-touched weight bearing for 10-12 weeks (n = 49)

Splint, short leg cast or foot ankle support

|

|

Age |

39 ± 15.2 |

36± 12.5 |

|

% male |

61.8% male |

67.9% male |

|

Severity/ injury classification |

AO/OTA (2007) A: 16/41 (39.0%) AO/OTA (2007) B: 25/41 (61%) |

AO/OTA (2007) A: 42/49 (85.7%) AO/OTA (2007) B: 7/49 (14.3%) |

|

Cause |

Road accident (including motor vehicle accident), crush, twist, high-energy fall, low energy fall * |

Road accident (including motor vehicle accident) crush, twist, high-energy fall, low energy fall * |

|

Van Dorp 2010

(Level 2 trauma center) |

Open reduction (n=3) Fixation with screws, K-wires, if necessary, with external fixator |

Lower leg cast or external fixator, with/without closed reduction (n=6)

|

|

Age |

19 ± 3.6 |

53 ± 23.3 |

|

% male |

33.3% |

33.3% |

|

Severity/classification |

No information |

No information |

|

Cause |

Motor vehicle accident, sports |

Motor vehicle accident, sports, sprain, fall. |

|

Richter 2004

(level 1 trauma center) |

Internal fixation with open or closed reduction (N=51) Fixation with K-wires, 3.5 cortical screws, if necessary, with external fixator

|

Closed reduction, no internal fixation (N=8) If necessary, application of a foot cast and rehabilitation with partial weight bearing for 6 weeks. |

|

Age |

32 (range: 17-85 years)* |

32 (range: 17-85 years)* |

|

% male |

68% male* |

68% male* |

|

Severity/classification |

Chopart fracture-dislocations or Chopart-Lisfranc fracture dislocations |

Pure Chopart joint dislocations |

|

Cause |

Motor vehicle accident, fall, contusion* |

Motor vehicle accident, fall, contusion* |

*Of the total study population, not specified per intervention

Results

Functional outcome

AOFAS-score

Two studies reported the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society Midfoot Score (AOFAS) (van Dorp, 2010; Richter 2004). Higher scores indicate better functioning of the foot, maximum score is 100 points. Van Dorp (2010) reported a higher AOFAS-score in the patients who underwent operative treatment (internal fixation) of the Chopart dislocations than the patients undergoing non-operative treatment, mean difference: 6.90 (95% CI: -32.98 to 46.78, Table 2). Richter (2004) reported a lower AOFAS-score for the patients undergoing operative treatment (internal fixation) for Chopart dislocations, (mean AOFAS: 73) than the patients undergoing non-operative treatment (mean AOFAS: 78, Table 2)

Table 2: Overview of the studies reporting AOFAS-score

|

|

Mean ± SD AOFAS Operative treatment |

Mean ± SD AOFAS Non-operative treatment |

Mean Difference (95% CI) |

|

Van Dorp 2010 (n = 9) |

75.7 ± 24.0 (n = 3) |

68.8 ± 29.8 (n = 6) |

6.90 (-32.98 to 46.78) |

|

Richter 2004 (n = 58) |

73 (n = 51) |

78 (n = 9) |

Can’t be calculated (no SD’s) |

AOFAS = American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society Midfoot Score; SD = Standard Deviation; 95% CI = 95% confidence intervals

Level of Activity

In Coulibaly (2015) functional outcome was reported by the number of patients who experienced full recovery of work and hobby activities. In the patients who underwent operative treatment (internal fixation) 26/41 (68.4%) experienced full recovery, compared to 38/49 (79.2%) in the patients undergoing non-operative treatment. The Risk Ratio (RR) was: 0.82 (95% CI: 0.62 to 1.08). This was not considered clinically relevant.

(Osteo)arthritis.

One study reported the outcome osteoarthritis (Coulibaly, 2015). It was reported that 35/41 (85.4%) of the patients undergoing operative treatment experienced secondary osteoarthritis, compared to 21/49 (42.9%) of the patients undergoing non-operative treatment. The risk ratio was 1.99 (95% CI: 1.41 to 2.82).

Need for arthrodesis

One study reported the outcome ‘need for arthrodesis’ (Coulibaly, 2015). It was reported that 7/41 (17.1%) of the patients undergoing operative treatment needed (secondary) arthrodesis, compared to 2/49 patients (4.1%) of the patients undergoing non-operative treatment. The risk ratio was 4.18 (95% CI: 0.92 to 19.04).

Adverse events

Infection

Two studies reported the outcome infection (Coulibaly, 2015; van Dorp, 2010). Coulibaly (2015) reported that 3/41 (7.3%) of the patients undergoing operative treatment experienced surgical site infections, compared to 2/49 (4.1%) of the patients undergoing non-operative treatment. The risk ratio was 1.79 (95% CI: 0.31 to 10.22). Van Dorp (2010) reported one infection in the operative treatment group (1/3; 33.2%). There were no infections in the patients undergoing non-operative treatment (0/4; 0%).

Avascular necrosis (AVN)

One study reported the outcome avascular necrosis (Coulibaly, 2015). It was reported that 1/41 (2.4%) of the patients undergoing operative treatment experienced avascular necrosis, compared to 0/49 (0%) of the patients undergoing non-operative treatment.

Duration of immobilization

One study reported the outcome duration of immobilization (Coulibaly, 2015). It was reported that the mean time to weight bearing was 11 ± 4.4 weeks in the patients undergoing operative treatment (n = 41), compared to 9 ± 5.4 weeks in the patients undergoing non-operative treatment (n = 49). Mean difference was 2.00 (95% CI: -0.02 to 4.02).

Signs of chronic instability

One study reported the number of nonunion, which is considered a sign of instability (Coulibaly, 2015). It was reported that 2/41 (4.9%) of the patients undergoing operative treatment experienced nonunion, compared to 1/49 (2.0%) of the patients undergoing non-operative treatment. The risk ratio was 2.39 (95% CI: 0.22 to 25.43).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure functional outcome was retrieved from observational studies and therefore started ‘low’. The level of evidence was downgraded by three levels because of study limitations including lack of adequate correction for confounding factors (-1 risk of bias); conflicting results (-1 inconsistency); and the 95% CI’s crossing the boundaries of clinical decision making (-1 imprecision). The final level of evidence was ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure arthritis was retrieved from observational studies and therefore started ‘low’. The level of evidence was downgraded by one level because of study limitations including lack of adequate correction for confounding factors (-1 risk of bias). The final level of evidence was ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure need for arthrodesis was retrieved from observational studies and therefore started ‘low’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations including lack of adequate correction for confounding factors (-1 risk of bias) and wide 95% confidence intervals (-1 imprecision) The final level of evidence was ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure adverse events was retrieved from observational studies and therefore started ‘low’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations including lack of adequate correction for confounding factors (-1 risk of bias) and wide 95% confidence intervals (-1 imprecision). The final level of evidence was ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure duration of immobilization was retrieved from observational studies and therefore started ‘low’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations including lack of adequate correction for confounding factors (-1 risk of bias) and wide 95% confidence intervals including 0 (-1 imprecision) The final level of evidence was ‘very low’.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure signs of chronic instability was retrieved from observational studies and therefore started ‘low’. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations including lack of adequate correction for confounding factors (-1 risk of bias) and wide 95% confidence intervals (-1 imprecision). The final level of evidence was ‘very low’.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and harms of operative treatment compared with conservative treatment for patients with diagnosed Chopart injuries after an acute trauma?

| P: | Patients with diagnosed Chopart injuries (fracture and/or dislocation) after an acute trauma |

| I: | Operative treatment |

| C: | Conservative treatment |

| O: | Functional outcome, (osteo)arthritis, need for secondary arthrodesis, adverse events, duration of immobilization and signs of chronic instability |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered functional outcome, arthritis and need for arthrodesis as critical outcome measures for decision making and infection and signs of chronic instability, duration of immobilization/non-weight bearing mobilization as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline development group decided that the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score was the preferred measure for functional outcome. If a study did not include the AOFAS-score but alternative measures for functional outcome were presented (e.g. mobility or Foot Function Index; FFI-score), these alternative measures were included in the summary of literature. For the other outcomes measures listed above, the guideline development group decided to use the definitions used in the studies.

For the predefined outcomes the guideline development group defined the minimal clinically (patient) important differences as follows:

- Functional outcome (AOFAS): 10 points

- Arthritis: Risk Ratio (RR) <0.80 and >1.25

- Need for arthrodesis: Risk Ratio (RR) <0.80 and >1.25

- Signs of chronic instability: Risk Ratio (RR) <0.80 and >1.25

- Duration of immobilization: more or less than 3 months

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until the 10th of January 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 346 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews, RCTs and observational studies comparing surgical treatment of Chopart injuries with conservative treatment. Studies were selected by three independent reviewers. Discrepancies were solved by consensus. Sixteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, thirteen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included.

Results

Three studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Coulibaly MO, Jones CB, Sietsema DL, Schildhauer TA. Results and complications of operative and non-operative navicular fracture treatment. Injury. 2015 Aug;46(8):1669-77. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.04.033. Epub 2015 May 7. PMID: 26058352.

- Richter M, Thermann H, Huefner T, Schmidt U, Goesling T, Krettek C. Chopart joint fracture-dislocation: initial open reduction provides better outcome than closed reduction. Foot Ankle Int. 2004 May;25(5):340-8. doi: 10.1177/107110070402500512. PMID: 15134617.

- van Dorp KB, de Vries MR, van der Elst M, Schepers T. Chopart joint injury: a study of outcome and morbidity. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010 Nov-Dec;49(6):541-5. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2010.08.005. PMID: 21035040.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Coulibaly 2015 |

Type of study: Retrospective cohort

Setting and country: Patients treated in a Level I trauma centre from March 2002 to June 2007, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: None |

Inclusion criteria: - patients with navicular fractures (radiographically diagnosed) - skeletal maturity - initial treatment at the study institution

Exclusion criteria: - stress fractures Unavailable radiographic images at injury and at final follow-up - follow-up < 3 months

N total: Intervention: 41/90 Control: 49/90 110 patients met inclusion criteria 62 (with 64 NF) were analysed

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD I: 39 ± 15,2 C: 36± 12,5

Sex: % male I: 61,8% male C: 67,9% male

Comorbidity index: I: 1.21 ± 1.7 C: 1.29 ± 1.3

Groups comparable at baseline? Probably no

|

Operative Treatment (ORIF)

- ORIF (n = 24, 58.5%) - ORIF with external fixator (n = 5, 12.2%) - ORIF with spanning plate (n = 12, 29.3%) proximal – TN joint (n = 0, 0%) distal – NC joint (n = 2, 4.9%) proximal & distal (n = 10, 24.4%)

Implants: - 2.0 plate (n = 21, 51.2%) - 2.7 plate (n = 9, 22.0%) - 2.0 plate and external fixation (n = 4, 9.8%) - 2.7 plate and external fixation (n = 1, 2.4%) - Screws (n = 9, 22.0%)

|

Non-operative treatment (NOT)

Patients remained toe-touch weight bearing in a splint, short leg cast, or Foot Ankle Support for ten to twelve weeks. Patients were instructed to begin range-of-motion (ROM) exercises at home and organized physical therapy for weight bearing, gait, ROM, and conditioning

|

Length of follow-up: Follow up at 2, 6, 12, 26 and 52 weeks

Average follow-up time: 23 ± 15.4 months

Min. follow-up duration: 3 months

Loss-to-follow-up: “22 were excluded because of skeletal immaturity (6), inadequate follow up (34) or incomplete radiographs (8)”

|

Functional outcomes: Pain (Yes) I: 21/41 (51.2%) C: 18/49 (36.7%)

Level of activity (full recovery) I: 26/41 (68.4%) C: 38/49 (79.2%)

Secondary osteoarthritis I: 35/41 (85.4%) C: 21/49 (42.9%)

Need for arthrodesis I: 7/41 (17.1%) C: 2/49 (4.1%)

Surgical site infection I: 3/41 (7.3%) C: 2/49 (4.1%)

Non-union – signs of instability I: 2/41 (4.9%) C: 1/49 (2.0%)

Time to immobilization Time to weight bearing (weeks) I: 11 ± 4.4 C: 9 ± 5.4

Time to healing (weeks) I: 16.1 ± 5.5 C: 16.2 ± 6.8 Avascular necrosis (AVN) I: 1/41 (2.4%) C: 0/49 (0%)

|

The authors concluded that: “Navicular fractures are uncommon and usually are associated with other injuries. Operative intervention is enhanced with bone grafting to support impacted fracture fragments. Despite alignment and anatomical restoration, secondary arthritis and pain are common. More severe injuries have worse results. Reduction quality relates to pain and return to function”

Baseline data only available for the 62 patients included in the analysis; data in the tables presented for 90 patients. LTFU unclear

Operative treatment related to increasing severity of fracture

22/41 patients who had ORIF also had secondary surgery for implant removal due to local irritation (16/41), breakage (3/41) and prominence (2/41). No significant difference as found in the rate of plate removal when comparing 2.0 – 2.7 mm plates.

|

|

Dorp 2010 |

Type of study: Retrospective case series

Setting and country: Patients treated at a level-2 trauma center between January 2004 and January 2010, NL

Funding and conflicts of interest: none |

Inclusion criteria: - Patients with joint-dislocation or fracture dislocation of the Chopart joint

Exclusion criteria: - Lisfranc fractures dislocations and isolated midfoot fractures

N total at baseline: Intervention: 3 Control: 6 n total = 9

Important prognostic factors2: age ± SD: I: 19 ± 3.6 C: 53 ± 23.3

Sex: % male I: 33.3% C: 33.3%

Groups comparable at baseline? Probably not

|

Open reduction

-screw fixation medical cuneiform + K-wire fixation TNJ + external fixator

- Screw fixation navicular + K-wire fixation TNJ

- Screw fixation navicular + external fixator

Patient 2, 4, 5

|

Lower leg cast or external fixator, with or without closed reduction

- Closed reduction + lower leg cast for 8 weeks - lower leg cast - lower leg cast 10 weeks - closed reduction + external fixator - lower leg cast - closed reduction + lower leg cast 8 weeks

Patient 1, 3, 6, 7, 8 9 |

Length of follow-up: Minimum 6 months Average was 31.3 ± 19.2 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Total: n = 2 Reasons: follow-up was less than 6 months Both from control population

|

Functional outcome: AOFAS Mean ± SD I: 75.7 ± 24.0 C: 68.75 ± 29.75

Level of activity – work (unchanged) I: 3/3 (100%) C 2/3 (66.7%) (One patient from control population was retired)

Pain (yes) I: 1/3 (33%) C: 2/4 (50%)

Level of activity – hobby (unlimited)

Patient satisfaction with outcome VAS |

The authors concluded that: Seven patients with an average follow-up of 31.3 ± 19.2 months reported a mean American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society midfoot score of 72 (range, 32-100) points and a mean visual analog scale score of 7.1 (range, 5-10). Four (57.14%) patients still experienced pain or had limitations in daily activities at the time of the final follow-up”.

The trauma mechanism was sprain or sports injury in 5 (55.6%), motor vehicle accident in 3 (33.33%), and a fall from height in 1 (11.11%) case |

|

Richter 2004 |

Type of study: Retrospective study

Setting and country: Patients treated in a level I trauma center Hannover (Germany) Medical school between January 1972 and December 1997

Funding and conflicts of interest: No information |

Inclusion criteria: - Traumatic dislocation or fracture dislocations of the Chopart joint

Exclusion criteria: - patients undergoing amputation - less than 2 years follow-up

N total at baseline: Intervention: 91 (83%) Control: 19 (17%) n total = 100 58 patients (with 59 fractures) were analysed

Important prognostic factors2: Not specified for intervention/control Age: 32 (range: 17-85 years)

Sex % male: 68% male

Groups comparable at baseline? Probably not |

- Closed reduction with internal fixation - Open with internal fixation ± external fixation Internal fixation with K-wires and/or 3.5 mm cortical screws After operation 2/3 days leg cast, then foot cast for 6 weeks |

Closed reduction, no internal fixation Nonoperative treatment included closed reduction, if necessary application of a foot cast and rehabilitation with partial weight bearing for 6 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: Average follow-up: 9 years (range 2 – 25 years)

Loss-to-follow-up: Total: n = 14 Reason: Amputation, deaths

|

AOFAS-score I: 73 C: 78 |

Chopart/Lisfranc fracture dislocations were also included

Classification of soft injuries from Tscherne and Oestern.

|

Risk of bias table for interventions studies (cohort studies based on risk of bias tool by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Author, year |

Selection of participants

Was selection of exposed and non-exposed cohorts drawn from the same population?

|

Exposure

Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?

|

Outcome of interest

Can we be confident that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study?

|

Confounding-assessment

Can we be confident in the assessment of confounding factors?

|

Confounding-analysis

Did the study match exposed and unexposed for all variables that are associated with the outcome of interest or did the statistical analysis adjust for these confounding variables?

|

Assessment of outcome

Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?

|

Follow up

Was the follow up of cohorts adequate? In particular, was outcome data complete or imputed?

|

Co-interventions

Were co-interventions similar between groups?

|

Overall Risk of bias

|

|

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Definitely yes, probably yes, probably no, definitely no |

Low, Some concerns, High |

|

|

Coulibaly 2015 |

Definitely yes

All consecutive patients presenting with injuries at one trauma centre |

Definitely yes

Reason: Yes, from hospital data |

Definitely yes

Reason: Outcomes after treatment and depending on treatment (e.g. infection, complication), functional outcomes compared to before trauma |

Definitely no;

Reason; confounders not taken into account |

Definitely no;

Reason: Patients receiving ORIF, often had more severe injuries |

Probably yes;

Reason: some of the outcome measures are subjective (e.g. pain) |

Probably yes;

Reason: frequent follow-up, not clear which patients were included in the analysis |

Probably yes;

Reason: intervention and control interventions clearly described |

High

All outcomes |

|

Van Dorp 2010 |

Definitely yes:

All consecutive patients with injuries presenting at one trauma centre |

Definitely yes;

Reason: patient files, surgical reports and picture archive were used to collect data |

Definitely yes:

Reason: functional outcomes compared to before the trauma |

Definitely no;

Reason; confounders not taken into account |

Definitely no:

Reason: patients receiving operative treatment on average were younger |

Probably yes;

Reason: some of the outcome measures are subjective (e.g. pain) |

Probably yes;

Reason: all patients had a min. follow-up for 6 months, missings were excluded |

Probably yes;

Reason: all interventions were described per patients, appear to be similar |

High

All outcomes |

|

Richter 2004 |

Probably yes:

Reason: all consecutive patients with injuries presenting at one trauma centre |

Probably yes;

Reason: probably based on hospital data but not clearly mentioned |

Probably yes:

Reason: identification of the situation after treatment

|

Definitely no;

Reason; confounders not taken into account |

Definitely no:

Reason; patients with more complex dislocations received operative treatment |

Probably yes

Reason: some of the outcome measures are subjective (e.g. pain) |

Probably no;

Reason: large proportion was missing, nog clear why. Broad range in FU period (2-25 years) |

Probably yes;

Reason: intervention and control interventions clearly described |

High

All outcomes |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Rammelt S, Missbach T. Chopart Joint Injuries: Assessment, Treatment, and 10-Year Results. J Orthop Trauma. 2023 Jan 1;37(1):e14-e21. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000002465. PMID: 35976798. |

Data not presented for operative management and non-operative management separate. |

|

Clements JR, Dijour F, Leong W. Surgical Management Navicular and Cuboid Fractures. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018 Apr;35(2):145-159. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2017.12.001. Epub 2018 Feb 1. PMID: 29482786. |

No systematic search was performed, search method is lacking |

|

Kutaish H, Stern R, Drittenbass L, Assal M. Injuries to the Chopart joint complex: a current review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2017 May;27(4):425-431. doi: 10.1007/s00590-017-1958-0. Epub 2017 Apr 17. PMID: 28417204. |

No systematic search was performed, search method is lacking |

|

Ortega Tapia C, Moreno Fernández L, Martínez Zaragoza J, Arias Baile A, Dalmau Coll A. Fracturas y Luxaciones de Chopart: Nuestro Algoritmo de Tratamiento. Revista del Pie y Tobillo. 2022;36(2). |

Article in Spanish |

|

Du X, Qu J, Wang J, Wu J, Ma H, Peng Y, Wang L. [CLASSIFICATION OF ADULT CUBOID FRACTURE AND EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2016 May 8;30(5):551-554. Chinese. doi: 10.7507/1002-1892.20160111. PMID: 29786293. |

Article in Chinese |

|

Engelmann EWM, Wijers O, Posthuma J, Schepers T. Management and Outcome of Hindfoot Trauma With Concomitant Talar Head Injury. Foot Ankle Int. 2021 Jun;42(6):714-722. doi: 10.1177/1071100720980023. Epub 2021 Jan 21. PMID: 33478268; PMCID: PMC8209765. |

Patients with talar neck fractures (with concomitant injuries, e.g. Chopart) |

|

Fenton P, Al-Nammari S, Blundell C, Davies M. The patterns of injury and management of cuboid fractures: a retrospective case series. Bone Joint J. 2016 Jul;98-B(7):1003-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.98B7.36639. PMID: 27365481. |

Results not presented for operative management versus. Non-operative management |

|

Frink, Michael, et al. "Etiology, treatment and long-term results of isolated midfoot fractures." Foot and ankle surgery 12.3 (2006): 121-125. |

Patients with midfoot injuries (Lisfranc + Chopart) |

|

Kotter A, Wieberneit J, Braun W, Rüter A. Die Chopart-Luxation. Eine häufig unterschätzte Verletzung und ihre Folgen. Eine klinische Studie [The Chopart dislocation. A frequently underestimated injury and its sequelae. A clinical study]. Unfallchirurg. 1997 Sep;100(9):737-41. German. doi: 10.1007/s001130050185. PMID: 9411801. |

Article in German |

|

Latoo IA, Wani IH, Farooq M, Wali GR, Kamal Y, Gani NU. Midterm functional outcome after operative management of midfoot injuries. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2014 Nov-Dec;16(6):639-44. doi: 10.5604/15093492.1135124. PMID: 25694378. |

Patients with midfoot injuries (Lisfranc + Chopart) |

|

Mestdagh H, Butruille Y, Mairesse JL, Gougeon F. Evolution et traitement des fractures du scaphoïde tarsien [Evolution and treatment of tarsal scaphoid fractures]. Acta Orthop Belg. 1984 Sep-Oct;50(5):601-16. French. PMID: 6516816. |

Article in French |

|

Richter M, Wippermann B, Krettek C, Schratt HE, Hufner T, Therman H. Fractures and fracture dislocations of the midfoot: occurrence, causes and long-term results. Foot Ankle Int. 2001 May;22(5):392-8. doi: 10.1177/107110070102200506. PMID: 11428757. |

Patients with midfoot injuries (Lisfranc + Chopart) |

|

Wallenböck E, Möstl H. Gibt es eine Operationsindikation für die Fraktur des Os naviculare pedis? [Is there a surgical indication for fracture of the os naviculare pedis?]. Zentralbl Chir. 1994;119(8):584-6. German. PMID: 7975949. |

Article in German |

|

Main BJ, Jowett RL. Injuries of the midtarsal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975 Feb;57(1):89-97. PMID: 234971. |

Outdated publication |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 10-09-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 10-09-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 10-09-2029

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in februari 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met traumatisch complexe voetletsels.

Werkgroep

- Dhr. dr. T. (Tim) Schepers (voorzitter werkgroep); traumachirurg, Amsterdam UMC, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH)

- Dhr. prof. dr. M. (Martijn) Poeze; traumachirurg, Maastricht UMC, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH)

- Dhr. dr. S.D. (Stijn) Nelen; traumachirurg, Radboud UMC Nijmegen, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH)

- Dhr. drs. B.E. (Bastiaan) Steunenberg; radioloog, Elisabeth-TweeSteden Ziekenhuis Tilburg, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie (NVvR)

- Dhr. drs. H.H. (Erik) Dol; SEH-arts, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, Nederlandse Vereniging van Spoedeisende Hulp Artsen (NVSHA)

- Dhr. drs. M.W. (Menno) Bloembergen; orthopedisch-chirurg, Reinier Haga Orthopedisch Centrum en Hagaziekenhuis, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging (NOV)

- Dhr. drs. J.P.S. (Joris) Hermus; orthopedisch-chirurg, Maastricht UMC, Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging (NOV)

- Dhr. E. (Erik) Wink; registerpodoloog/podotherapeut/fysiotherapeut, podologic/stichting Reyery, Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap Fysiotherapie (KNGF) en stichting LOOP (Landelijk Overkoepelend Orgaan Podologie)

- Dhr. drs. P.W.A. (Peter) Muitjens; revalidatiearts, Adelante Zorggroep, Nederlandse Vereniging van Revalidatieartsen (VRA)

Met ondersteuning van

- Mw. dr. A.C.J. (Astrid) Balemans, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

- Mw. MSc. D.G. (Dian) Ossendrijver, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Belangentabel richtlijnwerkgroep complexe voetletsels

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenwerkzaamheden |

Gemelde Persoonlijke Financiële Belangen |

Gemelde Persoonlijke Relaties |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek |

Gemelde Intell. belangen en reputatie |

Gemelde Overige belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Tim Schepers (voorzitter richtlijn complexe voetletsels) |

Traumachirurg voltijd Amsterdam UMC

|

Voet-enkel expert groep van de Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO)

|

Geen |

Geen |

Ja: wifi2 studie naar wondinfecties bij voet+enkel operaties (verwijderen schroeven/plaat): https://www.amc.nl/web/research-75/trials-collaborations/wifi-2.htm. De studie richt zich op de effectiviteit van antibiotica op het voorkomen van infecties. Rol als projectleider. Gefinancierd roor ZonMW, direct aan Amsterdam Medical Research |

Geschat +/- 200 publicaties over voet- enkelletsel

|

Geen |

Geen restricties; geen van de modules gaat over het onderwerp van de wifi2 studie |

|

Stijn Nelen |

Traumachirurg Radboud UMC Nijmegen |

ATLS-instructeur |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Martijn Poeze |

Traumachirurg Maastricht UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Bastiaan Steunenberg |

Radioloog Isala Zwolle |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Erik Dol |

SEH-arts KNMG |

ATLS-instructeur |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Menno Bloembergen |

Orthopedisch chirurg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Joris PS Hermus |

Orthopedisch chirurg-traumatoloog |

Voet-enkel expert groep van de Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO)

Council member & honorary secretary European Foot and Ankle Society |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Erik Wink |

Registerpodoloog podotherapeut bij podologic |

Fysiotherapeut bij reyerey, langebaan schaatsploeg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Peter Muitjens |

Revalidatiearts 0,8 fte, betaald |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van Patiëntenfederatie Nederland (PFN) voor de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Chopart letsel |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zullen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met traumatisch complex voetletsel. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model (Review Manager 5.4) werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.