Stoppen met roken bij een perioperatief traject

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van een perioperatie traject gericht op het stoppen met roken bij rokers die een operatie moeten ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Adviseer een rokende patiënt om te stoppen met roken, door middel van een VBA+, voorafgaand aan een operatie vanwege het verhoogde risico op het ontstaan van postoperatieve complicaties bij rokers1.

Zie voor verwijzingen module Begeleiding van stoppen met roken na ontslag.

1Zie ook 'Tijdstip en duur van preoperatief stoppen met roken' uit de overwegingen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor deze module is een literatuuranalyse gedaan naar de uitkomsten van een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie bij rokende patiënten die een electieve operatie moeten ondergaan. Hierbij zijn twee studies gevonden, waaronder een systematische review van RCT’s en één separate RCT. Voor de cruciale uitkomsten complicaties en secundaire chirurgie was de bewijskracht laag, vanwege studielimitaties (het ontbreken van blindering van patiënten en studiepersoneel) en een breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval van de effectschatter. Voor de cruciale uitkomst ‘stoppen met roken’ is de bewijskracht gemiddeld voor een positief effect van een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie. Er werd geen bewijs gevonden voor een effect van een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie op de uitkomstmaten mortaliteit (cruciale uitkomstmaat) en duur van ziekenhuisopname (belangrijke uitkomstmaat). De algehele bewijskracht van de gevonden studies is laag.

De werkgroep heeft succesvol stoppen met roken gedefinieerd als onthouding van roken gedurende minimaal zes maanden. In de gevonden literatuur is de stoppen-met-rokeninterventies gegeven enkele weken tot enkele maanden voor de operatie, met één studie waarbij slechts enkele dagen voor de operatie de interventie gegeven is. De gevonden literatuur met een redelijke bewijskracht geeft een positief effect op stoppen met roken na twaalf maanden aan. Het is dan ook aannemelijk dat na zes maanden dit bewijs sterker is.

In een studie van Sørensen (2003), die eveneens geïncludeerd was in de systematische review van Thomson (2014,) werd aan patiënten in de controlegroep gevraagd door te blijven roken. Deze studie liet een minimaal verschil zien van de interventie met betrekking tot postoperatieve complicaties. In totaal had 11/27 (41%) patiënten die een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie kregen een of meerdere complicaties na de operatie, vergeleken met 13/30 (43%) patiënten die verzocht werd door te blijven roken. Deze studie zou in deze tijd niet voldoen aan de Wet Medisch-wetenschappelijk Onderzoek met mensen (WMO). Een kanttekening die vervolgens geplaatst dient te worden bij de literatuuranalyse is dat in de controlegroepen van de studies een minimaal stoppen-met-rokenadvies (very brief advice) gegeven werd, waarbij hoogstens slechts kort benoemd werd dat men moest stoppen met roken. Vanuit de werkgroep wordt dit geacht als standaardbehandeling, maar in de huidige praktijk blijkt dat het vragen en registeren naar rookgedrag weinig wordt gedaan. Hierdoor zou het daadwerkelijke effect van een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie hoger kunnen liggen. De literatuur search bevat daarnaast alleen RCT’s, aangezien deze een hogere bewijskracht kunnen leveren. Mogelijk nadeel is dat deze studies alleen patiënten hebben geïncludeerd met een a priori motivatie om te stoppen met roken. Het effect van de interventie en de controlegroep kan mogelijk zijn overschat. Een review van de World Health Organization (WHO) met daarin 29 systematische en narratieve reviews heeft laten zien dat roken een significante positieve associatie heeft met het risico op postoperatieve complicaties (WHO, 2020). Diverse observationele studies hebben daarnaast aangetoond dat het stoppen met roken leidt tot een vermindering van het aantal complicaties na operatie (Ayazi, 2021; Heiden, 2021; Quan, 2019).

Er zijn, naast het mogelijk ontstaan van nicotine ontrekkingsverschijnselen, geen verdere nadelige effecten van een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie bekend. Wel kan het blijven roken, ondanks een stoppen-met-rokenpoging, er in enkele gevallen voor zorgen dat operaties moeten worden uitgesteld. Dit gebeurt in de praktijk onder andere bij Reinkes oedeem. Ook bij plastische chirurgie heeft het de voorkeur te stoppen met roken voor operaties, in verband met mogelijk slechtere wondgenezing.

Tijdstip en duur van preoperatief stoppen met roken

Het optimale tijdstip en duur van preoperatief stoppen met roken is niet goed onderzocht en daarom lastig te vermelden. Een systematische review van Wong (2012) concludeerde dat stoppen met roken minstens drie tot vier weken voor een operatie gewenst is om complicaties t.a.v. wondgenezing te voorkomen. De systematische review is echter gedateerd en omvat vrijwel exclusief observationele studies. Voor een aanbeveling rondom het tijdstip en duur van stoppen met roken zijn RCT’s van goede kwaliteit nodig, die tot op heden ontbreken.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De voordelen van stoppen met roken voor patiënten is onder andere kostenbesparing. Bovendien is er algehele gezondheidswinst te behalen door te stoppen met roken, los gezien van operaties. Het is eveneens bekend dat patiënten over het algemeen positief staan tegenover een stoppen-met-rokeninterventie wanneer dit wordt aangeboden voor men een operatie dient te ondergaan. Een enquête van het Longfonds (zie module Begeleiding van stoppen met roken na ontslag) heeft, verspreid over meerdere jaren, laten zien dat patiënten die opgenomen zijn in het ziekenhuis over het algemeen tevreden zijn met een gesprek met de zorgverlener over stoppen met roken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Voor de algehele maatschappij brengen stoppen-met-rokeninterventies geen belangrijke kosten met zich mee. Stoppen met roken zal geen harde euro’s aan winst op leveren, maar wel winst in kwaliteit van leven en levensduur voor de patiënt. Dit is met name bij electieve operaties, doordat dit in het algemeen mensen betreft met een nog aanzienlijke levensverwachting.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Om te zorgen dat zorgverleners ook daadwerkelijk rokers motiveren en verwijzen voor een stoppen-met-rokenpoging, is het belangrijk om meer bewustzijn te creëren onder zorgverleners over de positieve effecten van stoppen met roken. Dit om te waarborgen dat men ook daadwerkelijk gaat vragen of een patiënt rookt of niet. Ook zou het kunnen helpen een specifieke plaats in het epd aan te wijzen om deze informatie op te schrijven. Vervolgens is het belangrijk om bij de zorgverlener duidelijk te krijgen waar men een patiënt heen kan verwijzen indien deze gemotiveerd is om te stoppen met roken. Door duidelijkheid in de mogelijkheden tot verwijzen kan tijd worden bespaard, die nu vaak ontbreekt. Het is belangrijk te zorgen voor een warme verwijzing middels de VBA+ naar een in het kwaliteitsregister geregistreerd (externe) stoppen-met-rokencoach of organisatie (zie ook module Begeleiding van stoppen met roken na ontslag).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Literatuur laat zien dat stoppen-met-rokeninterventies voor een operatie kunnen leiden tot het daadwerkelijk stoppen met roken en gestopt blijven. Literatuur laat eveneens zien dat roken het risico op postoperatieve complicaties verhoogt en dat (een interventie gericht op ) stoppen met roken dit risico kan verlagen. Een patiënt zal door te stoppen direct kosten besparen en de algehele gezondheid verbeteren. De werkgroep raadt dan ook aan om iedere patiënt te adviseren om te stoppen met roken voor deze een operatie zal ondergaan. Het behoort tot de taak van de zorgverlener om altijd te vragen naar het rookgedrag van patiënt en dit te registeren. De patiënt dient doorverwezen te worden naar een stoppen-met-rokenprogramma voor de begeleiding bij het stoppen met roken.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het percentage rokers van de totale Nederlandse bevolking schommelt al een aantal jaren rond de 20%, waarvan bijna driekwart dagelijks rookt (Trimbos, 2022). Naast bekende negatieve gevolgen als een verhoogd risico op hart- en vaatziekten en diverse vormen van kanker, is ook duidelijk dat roken een verhoogde kans geeft op postoperatieve complicaties (WHO, 2020). Begeleiding van patiënten bij het stoppen met roken vergt discipline en tijd, waarbij de vraag rijst of een stoppen-met-rokenprogramma voorafgaand aan een operatie effectief is in het vergroten van de kans op het succesvol stoppen met roken, het verkorten van de opnameduur en het verlagen van het risico op postoperatieve complicaties.

Conclusies

Smoking cessation

|

Moderate GRADE

Moderate GRADE

|

At time of surgery A smoking cessation intervention likely increases successful smoking cessation at the time of surgery when compared with usual care in smokers who need elective surgery.

12 months postoperatively A smoking cessation intervention likely increases smoking cessation 12 months postoperatively when compared with usual care in smokers who need elective surgery.

Thomsen, 2014; Wong, 2017 |

Complications

|

Low GRADE |

A smoking cessation intervention may reduce the risk of complications when compared with usual care in smokers who need elective surgery.

Thomsen, 2014; Wong, 2017 |

Secondary surgery

|

Low GRADE |

A smoking cessation intervention may reduce the risk of a secondary surgery when compared with usual care in smokers who need elective surgery.

Thomsen, 2014 |

Mortality

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of a smoking cessation intervention on mortality when compared with usual care in smokers who need elective surgery. |

Length of hospital stay

|

No GRADE |

Inconsistent evidence was found regarding the effect of a smoking cessation intervention on length of hospital stay when compared with usual care in smokers who need elective surgery.

Thomsen, 2014 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The systematic review by Thomsen (2014) investigated the effect of preoperative smoking interventions on smoking cessation in smokers prior to surgery (any type). The aim of the review was to assess the evidence for preoperative smoking interventions on smoking cessation at surgery and 12 months after surgery, as well as on the incidence of postoperative complications. Relevant studies until January 2014 were searched in the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register. Selection criteria included RCTs that recruited patients who smoked prior to surgery, were offered a smoking intervention, and measured both short- and long-term abstinence of smoking and/or measured the incidence of postoperative complications. A total of eleven RCT’s (excluding two incorrect RCTs, according to PICO, included by the authors of the review) were included in the systematic review.

Eleven RCTs included a total of 1783 patients. The majority of the studies offered counselling sessions, referrals to stop services and/or nicotine replacement therapy for several weeks to a few days before surgery (Andrews, 2006; Lee, 2013; Lindström, 2008; Møller, 2002; Ratner, 2004; Sørensen, 2007; Thomsen, 2010; Warner, 2012; Wolfenden, 2005; Wong, 2012). One study offered brief advice on smoking cessation in both the intervention and the control group, while the intervention group also received a warning that exhaled carbon dioxide would be monitored on the morning to check compliance (Shi, 2013). In the study of Warner (2012) both the intervention and the control group received a two-minute counselling session in combination with lozenges (resp. nicotine or placebo). In the study of Wong (2012) varenicline was used as intervention, next to counselling sessions. The study data from Shi (2013), Warner (2012) and Wong (2017) will be analysed separately, as the interventions in these studies differ substantially from the other included studies. The mean proportion of males ranged from 38% to 53%, with one study consisting of 85% males (Sørensen, 2007) and one study of only females (Thomsen, 2010). Mean age was reported by eight studies, ranging from 43 to 57 years. Median age was reported in three studies, ranging from 55 to 65 years. Daily cigarette consumption was reported in eight studies, ranging from 12 to 18 cigarettes per day. One study reported 45% of participants to smoke ≤10 cigarettes/day and 55% >10 cigarettes/day (Shi, 2013). One study only included only patients who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes/day (Wong, 2012). One study (Andrews, 2006) did not report patient characteristics.

Study outcomes included smoking cessation at surgery and 12 months postoperatively, postoperative complications, wound complications, secondary surgery, mortality and length of hospital stay.

Wong (2017) conducted a randomized controlled trial in Canada to investigate the effect of a smoking cessation program compared with a brief advice to increase short-term and long-term abstinence of smoking in surgical patients. The study only included adult patients who smoked ≥ 10 cigarettes/day. A total of 296 adult patients scheduled for ambulatory or inpatient surgery were randomized into an intervention group (n = 151) or a control group (n = 145). The intervention group received a combination of a 10–15-minute counseling session, pharmacotherapy with free supply of varenicline, an educational pamphlet and a fax referral to a quit line for proactive phone counseling and follow-up. The control group received brief advice regarding smoking cessation and information for a quit line for self-referral. In the intervention group, patients were on average less often male (58% vs. 67%) and smoked slightly less (16.2 cig/day vs. 18 cig/day) compared to the intervention group. Study groups were similar in age (I: 51.4 years vs. C: 52.3 years). Study outcomes included smoking cessation one month, three months, six months, and twelve months postoperatively and postoperative complications. A study limitation includes the possibility of overlapping study populations with the study by Wong (2012), included in the systematic review by Thomsen (2014). Study participants were recruited from the same hospital with non-overlapping recruiting periods. Although one of the exclusion criteria of the study by Wong (2017) was the use of nicotine replacement in the previous three months, this does not exclude the inclusion of participants included in the previous study (Wong, 2012).

Results

Smoking cessation

All included studies reported on the outcome smoking cessation. Thomsen (2014) defined smoking cessation as smoking abstinence at self-reported point prevalence or continuous abstinence at surgery or after 12 months. Wong (2017) defined smoking cessation as 7-day point prevalence abstinence as well as continuous abstinence after one month, three months, six months, and 12 months. To harmonize the results of the systematic review and the trial, only the outcomes after 12 months were described. The results were reported in the evidence table.

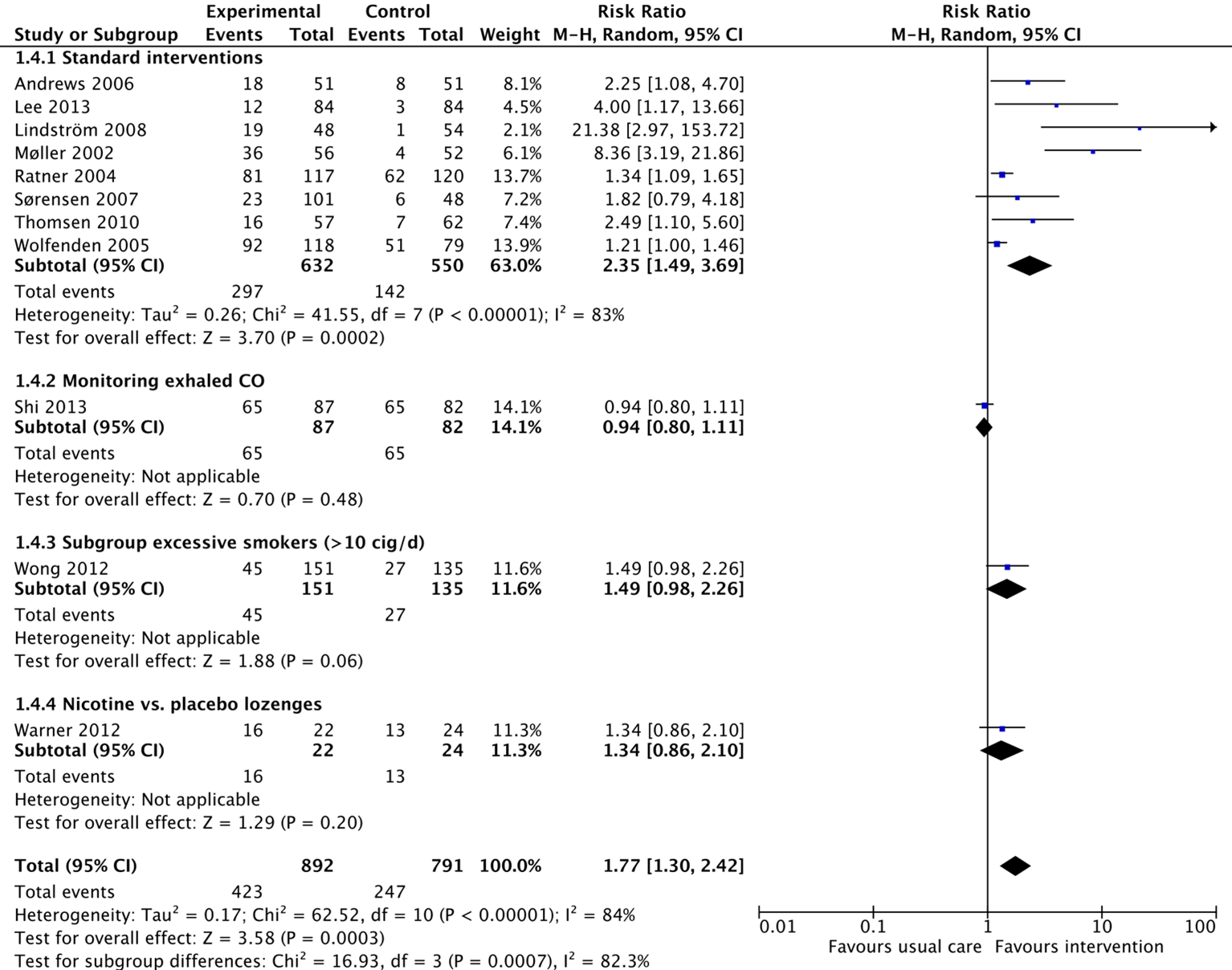

- Smoking cessation at surgery

All individual studies from the review by Thomsen (2014) reported on the outcome smoking cessation at surgery. In total, 423/892 patients (47%) from the intervention group receiving a smoking cessation intervention stopped with smoking at surgery, compared to 247/791 patients (31%) from the control group. The corresponding risk ratio is 1.77 (95%CI 1.30 to 2.42) in favour of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. The study of Shi (2013) reported that 65/87 patients (75%) from the intervention stopped smoking at surgery, compared to 65/82 patients (79%) from the control group. The corresponding risk ratio for this difference is 0.94 (95%CI 0.80 to 1.11) in favour of the control group, which is not considered clinically relevant. The effect of the result of the study by Shi (2013) on the total effect estimate of all studies, is negligible.

Figure 1. Forest plot showing the comparison between interventions focussed on smoking cessation compared with usual care on smoking cessation at surgery. Subanalyses for interventions with monitoring of exhaled CO, exclusion of light smokers and use of nicotine vs. placebo lozenges. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

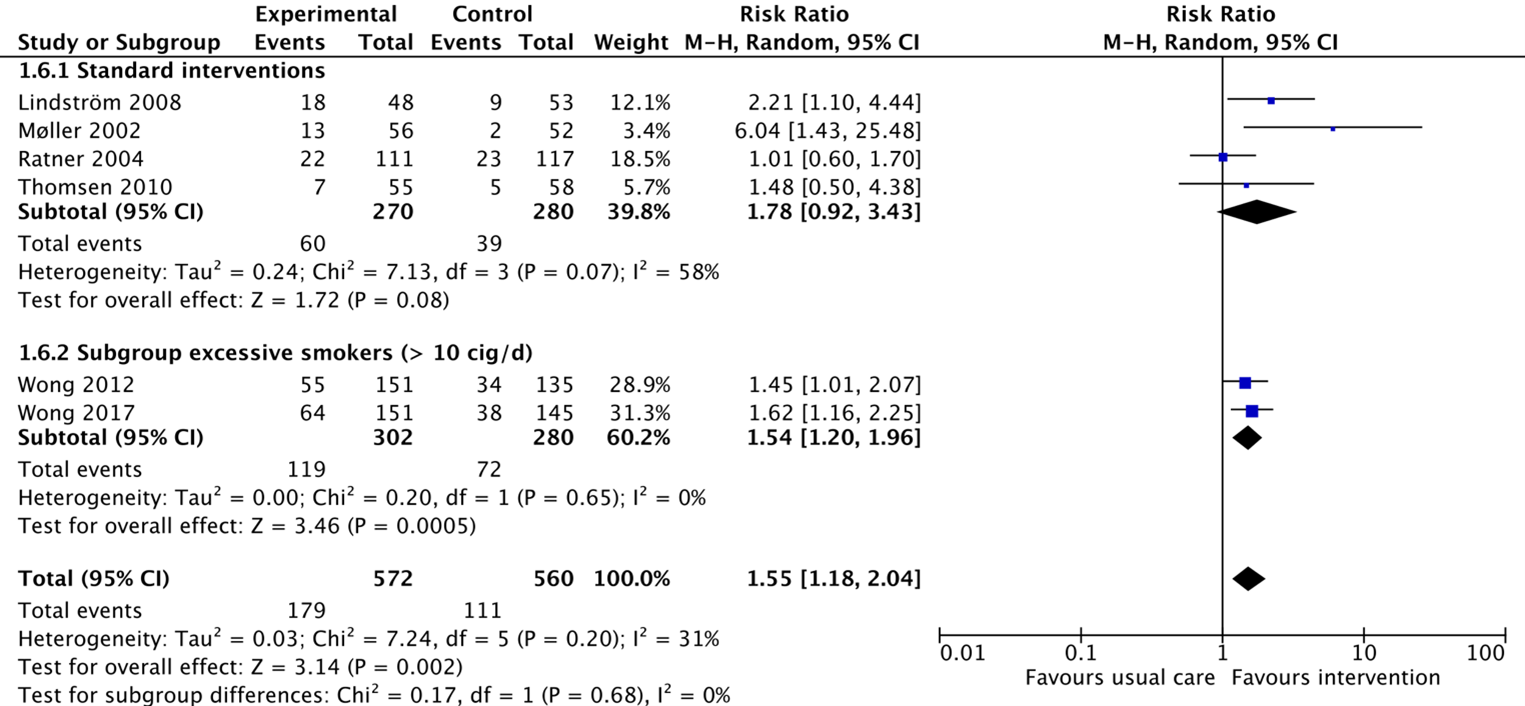

- Smoking cessation 12 months postoperatively

Five of the studies from Thomsen (2014) reported on the outcome smoking cessation after 12 months (Lindström, 2008; Møller, 2002; Ratner, 2004; Thomsen, 2010; Wong, 2012). Wong (2017) reported on smoking cessation after 12 months as well.

In total, 179/572 patients (31%) from the intervention group receiving a standard intervention stopped smoking after 12 months, compared to 111/560 patients (20%) from the control group. The corresponding risk ratio 1.55 (95%CI 1.18 to 2.04) is in favour of the intervention group. The effect is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the comparison between interventions focussed on smoking cessation compared with usual care on smoking cessation 12 months postoperatively. Subanalysis for study with exclusion of light smokers. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

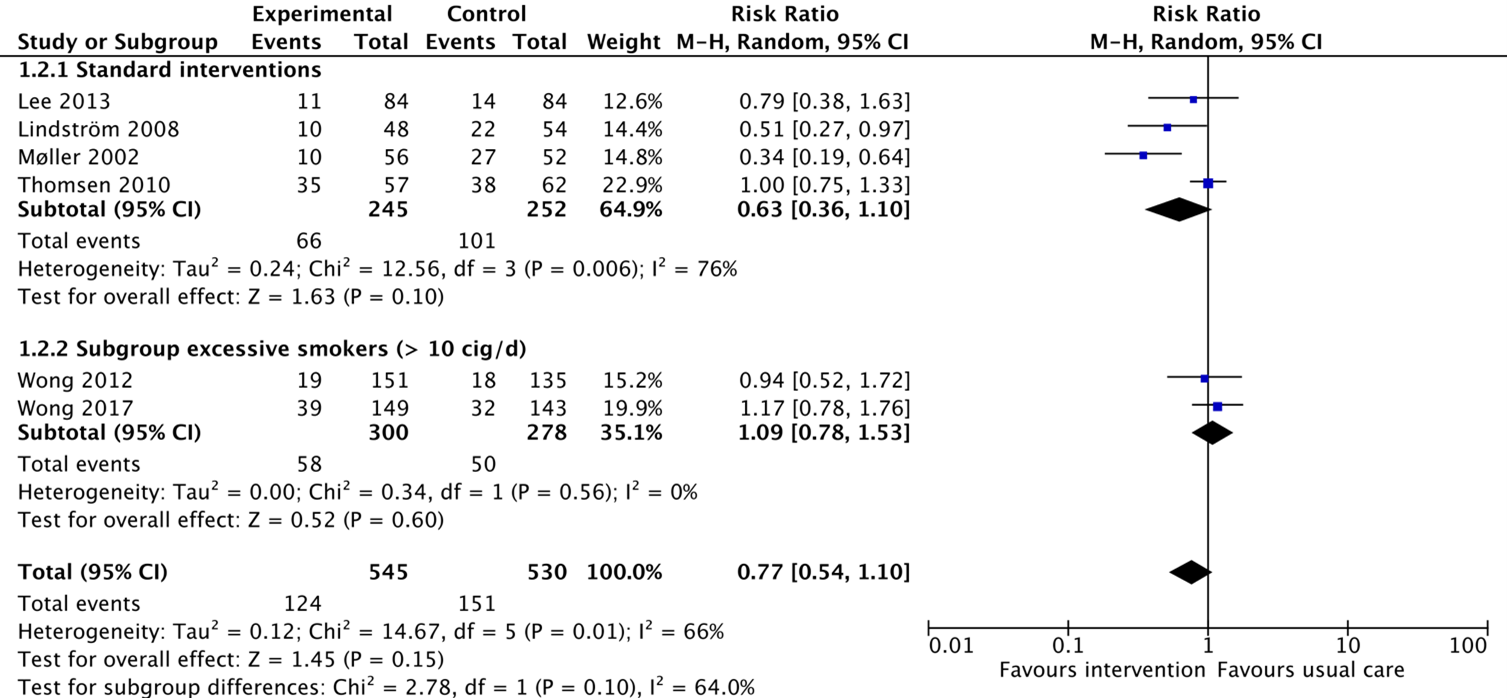

Complications

All of the included studies reported on the outcome complications (Thomsen, 2014; Wong, 2017). From the study by Thomsen (2014), four individual studies reported on this outcome as postoperative complications (Lee, 2013; Lindström, 2008; Møller, 2002; Thomsen, 2010; Wong, 2012). In total, 66/245 patients (27%) from the intervention group receiving standard interventions experienced complications, compared to 101/252 patients (40%) from the control group. The corresponding risk ratio is 0.63 (95%CI 0.36 to 1.10) in favour of the intervention group, which is considered clinically relevant. The study by Wong (2012) reported complications in 19/151 patients (13%) from the intervention group, compared to 18/135 patients (13%) from the control group. The corresponding risk ratio is 0.94 (95%CI 0.52 to 1.72) in favour of the intervention group, which is not considered clinically relevant. Wong (2017) reported that complications after surgery occurred in 39/149 (26%) of patients from the intervention group, compared to 32/143 (22%) patients from the control group. The corresponding risk ratio is 1.17 (95%CI 0.78 to 1.76) in favour of the control group, which is not considered clinically relevant. It is unclear for all reported studies to what extent complications occurred in patients who quitted smoking versus patients who continued smoking.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the comparison between interventions focussed on smoking cessation compared with usual care on complications perioperatively. Pooled relative risk ratio, random effects model. Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; SD: standard deviation; I2; statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval.

Secondary surgery

From the review by Thomsen (2014), two individual studies reported on the outcome secondary surgery (Møller, 2002; Thomsen, 2010). Møller (2002) reported that secondary surgery was performed in 2/56 patients (4%) from the intervention group (reposition of prothesis (n = 1), wound-related surgery, n = 1), compared to 8/52 patients (15%) from the control group (wound-related surgery (n = 7), vascular-related surgery (n = 1)). Thomsen (2010) reported one patient from the intervention group (n = 58) in which secondary surgery was performed (surgery due to haemotoma), compared to no patients in the control group (n = 62).

Mortality

None of the included studies reported on the outcome mortality.

Length of hospital stay

From the review by Thomsen (2014), four individual studies reported on length of hospital stay (Lee, 2013; Lindström, 2008; Møller, 2002; Thomsen, 2010). The results of these studies can be found in Table 1. A pooled analysis for the results was not possible, due to the reporting of the results in median length of stay. The results may suggest a similar length of stay for both study groups, with a minor shorter stay for the intervention group. The study by Møller, 2002 included only patients who were scheduled for primary elective hip or knee alloplasty, which may explain the longer hospital stay in both groups.

Table 1 Median hospital length of stay for interventions focused on smoking cessation compared with usual care.

|

Study |

Median hospital stay (days) |

|

|

Intervention |

Control |

|

|

Lee, 2013 |

1.75 (IQR 1 to 10) |

2.1 (IQR 1.3 to 3.2) |

|

Lindström, 2008 |

1 (range 1 to 10) |

1 (range 1 to 11) |

|

Møller, 2002 |

11 (range 7 to 75) |

13 (range 8 to 85) |

|

Thomsen, 2010 |

2 (range 1 to 7) |

3 (range 1 to 8) |

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure smoking cessation came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. This was downgraded by 1 level to moderate for both the outcome smoking cessation at surgery and smoking cessation 12 months postoperatively, because of study limitations (no blinding of participants and personnel in most studies, downgraded 1 level for risk of bias).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure complications came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. This was downgraded by 2 levels to low, because of study limitations (no blinding of participants and personnel in most studies, downgraded 1 level for risk of bias) and imprecision (overlap of the lower clinical threshold which indicates a potential non-clinically relevant effect, downgraded 1 level for imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure secondary surgery came from RCT’s and therefore started as high. This was downgraded by 2 levels to very low, because of study limitations (no blinding of participants and personnel in most studies, downgraded 1 level for risk of bias) and imprecision (optimal information size (n = 465 per study group) not reached, downgraded 1 level for imprecision).

No evidence was found regarding the outcome measure mortality. Therefore, the level of evidence could not be assessed.

Inconsistent evidence was found for the outcome measure length of hospital stay. Therefore, the level of evidence could not be assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the (un)desirable effects of an intervention with the aim of smoking cessation compared to usual care in smokers who need to undergo elective surgery?

P: Smokers of any age who need elective surgery

I: Any intervention with a focus on smoking cessation

C: Usual care

O: Smoking cessation, complications, secondary surgery (due to complications), mortality, length of hospital stay

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered smoking cessation, complications, secondary surgery and mortality as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and length of hospital stay as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcomes measures as follows:

Success smoking cessation is defined as abstinence at six months from the quit date as suggested by the workgroup group formed by the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (Hughes, 2003). For the other outcomes measures, the definitions were used as reported in the studies.

The working group defined the GRADE standard threshold of a risk ratio (RR) of 0.8 or 1.25 for the outcome measures smoking cessation, complications and second surgery. A threshold of an RR of 1.04 or 0.96 was set for the outcome all-cause mortality. The threshold was set at one day for the outcome measure length of stay.

Search and select (Methods)

A Cochrane review by Thomsen (2014) was used as primary source. This systematic review performed a literature search until January 2014. For this question, the search was updated. The databases [Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) and Cinahl] were searched with relevant search terms from 2014 until 26 October 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 74 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criterium: Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials that fulfill the PICO. Five studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, three studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included (Bohlin, 2020; Wong 2017). However, the study by Bohlin (2020) had ≥50% loss-to-follow-up making the results difficult to interpret. Therefore, only the results from Wong (2017) were described and included, next to the systematic review by Thomsen (2014).

For both studies by Wong (2012 & 2017), study participants were recruited from the same two hospitals with a non-overlapping recruiting period. It is however unclear if participants could have been included in both studies. Therefore, the results might overestimate the effect. Taking this into account, both studies are included in this literature research.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature, of which one was a systematic review (Thomsen, 2014) and one a randomized controlled trial (Wong 2017). In the current literature review, two studies of the systematic review by Thomsen (2014) were not included in this literature analysis, because of control groups that did not match with the PICO. For one of these studies, patients in the control group were encouraged to continue smoking (instead of usual care). In the other study, patient in the control group received another intervention for abstinence of smoking. Important study characteristics and results were summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias was summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Andrews K, Bale P, Chu J, Cramer A, Aveyard P. A randomized controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of a letter from a consultant surgeon in causing smokers to stop smoking pre-operatively. Public Health. 2006 Apr;120(4):356-8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.10.013. Epub 2006 Feb 13. PMID: 16473379.

- Ayazi K, Sayadi S, Hashemi M, Ghodssi-Ghassemabadi R, Samsami M. Preoperative Smoking Cessation and its Association with Postoperative Complications and Length of Hospital Stay in Patients Undergoing Herniorrhaphy. Tanaffos. 2021 Jan;20(1):59-63. PMID: 34394371; PMCID: PMC8355936.

- Bohlin KS, Löfgren M, Lindkvist H, Milsom I. Smoking cessation prior to gynecological surgery-A registry-based randomized trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020 Sep;99(9):1230-1237. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13843. Epub 2020 Apr 15. PMID: 32170727.

- Heiden BT, Eaton DB Jr, Chang SH, Yan Y, Schoen MW, Chen LS, Smock N, Patel MR, Kreisel D, Nava RG, Meyers BF, Kozower BD, Puri V. Assessment of Duration of Smoking Cessation Prior to Surgical Treatment of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Surg. 2023 Apr 1;277(4):e933-e940. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005312. Epub 2021 Nov 18. PMID: 34793352; PMCID: PMC9114169.

- Lee SM, Landry J, Jones PM, Buhrmann O, Morley-Forster P. The effectiveness of a perioperative smoking cessation program: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Analg. 2013 Sep;117(3):605-613. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318298a6b0. Epub 2013 Jul 18. PMID: 23868890.

- Lindström D, Sadr Azodi O, Wladis A, Tønnesen H, Linder S, Nåsell H, Ponzer S, Adami J. Effects of a perioperative smoking cessation intervention on postoperative complications: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2008 Nov;248(5):739-45. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181889d0d. PMID: 18948800.

- Møller AM, Villebro N, Pedersen T, Tønnesen H. Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):114-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07369-5. PMID: 11809253.

- Hughes JR, Keely JP, Niaura RS, Ossip-Klein DJ, Richmond RL, Swan GE. Measures of abstinence in clinical trials: issues and recommendations. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003 Feb;5(1):13-25. Erratum in: Nicotine Tob Res. 2003 Aug;5(4):603. PMID: 12745503.

- Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Richardson CG, Bottorff JL, Moffat B, Mackay M, Fofonoff D, Kingsbury K, Miller C, Budz B. Efficacy of a smoking-cessation intervention for elective-surgical patients. Res Nurs Health. 2004 Jun;27(3):148-61. doi: 10.1002/nur.20017. PMID: 15141368.

- Quan H, Ouyang L, Zhou H, Ouyang Y, Xiao H. The effect of preoperative smoking cessation and smoking dose on postoperative complications following radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a retrospective study of 2469 patients. World J Surg Oncol. 2019 Apr 2;17(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12957-019-1607-7. PMID: 30940207; PMCID: PMC6446305.

- Shi Y, Ehlers S, Hinds R, Baumgartner A, Warner DO. Monitoring of exhaled carbon monoxide to promote preoperative smoking abstinence. Health Psychol. 2013 Jun;32(6):714-7. doi: 10.1037/a0029504. Epub 2012 Aug 27. PMID: 22924451.

- Sørensen LT, Hemmingsen U, Jørgensen T. Strategies of smoking cessation intervention before hernia surgery--effect on perioperative smoking behavior. Hernia. 2007 Aug;11(4):327-33. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0229-0. Epub 2007 May 15. PMID: 17503161.

- Thomsen T, Tønnesen H, Okholm M, Kroman N, Maibom A, Sauerberg ML, Møller AM. Brief smoking cessation intervention in relation to breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010 Nov;12(11):1118-24. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq158. Epub 2010 Sep 20. PMID: 20855414.

- Thomsen T, Villebro N, Møller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Mar 27;2014(3):CD002294. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002294.pub4. PMID: 24671929; PMCID: PMC7138216.

- Trimbos-instituut. 2022 Cijfers rokers. Trimbos-instituut, Accessed 2023 March 10. < https://www.trimbos.nl/kennis/cijfers/roken/>

- Warner, D. O., and S. Kadimpat. Nicotine Lozenges to Promote Brief Preoperative Abstinence from Smoking: Pilot Study. Clin. Health Prom. 2012 Oct; 2(3) 85-88. doi:10.29102/clinhp.12012.

- WHO. 2020. Tobacco & Postsurgical outcomes. World Health Organization, Accessed 2023 March 10.

- Wolfenden L, Wiggers J, Knight J, Campbell E, Rissel C, Kerridge R, Spigelman AD, Moore K. A programme for reducing smoking in pre-operative surgical patients: randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia. 2005 Feb;60(2):172-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04070.x. PMID: 15644016.

- Wong J, Abrishami A, Yang Y, Zaki A, Friedman Z, Selby P, Chapman KR, Chung F. A perioperative smoking cessation intervention with varenicline: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2012 Oct;117(4):755-64. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182698b42. PMID: 22890119.

- Wong J, Abrishami A, Riazi S, Siddiqui N, You-Ten E, Korman J, Islam S, Chen X, Andrawes MSM, Selby P, Wong DT, Chung F. A Perioperative Smoking Cessation Intervention With Varenicline, Counseling, and Fax Referral to a Telephone Quitline Versus a Brief Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Analg. 2017 Aug;125(2):571-579. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001894. PMID: 28319515.

- Wong J, Lam DP, Abrishami A, Chan MT, Chung F. Short-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2012 Mar;59(3):268-79. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9652-x. Epub 2011 Dec 21. PMID: 22187226.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Thomsen, 2014

[individual study characteristics deduced from Thomsen, 2014 and individual articles]

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCT’s

Literature search up to 2014

A: Andrews, 2006 B: Lee, 2013 C: Lindström, 2008 D: Møller, 2002 E: Ratner, 2004 F: Shi, 2013 G: Sørensen, 2007 H: Thomsen, 2010 I: Warner, 2012 J: Wolfenden, 2005 K: Wong, 2012

Study design: RCT, parallel

Country: A: United Kingdom B: Canada C: Sweden D: Denmark E: Canada F: United States G: Denmark H: Denmark I: United States J: Australia K: Canada

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: no information B: non-commercial C: non-commercial (except for inter-vention product) D: non-commercial (except for inter-vention product), no conflict of interest reported E: non-commercial F: no information G: non-commercial (except for inter-vention product) H: non-commercial (except for inter-vention product) I: no conflicts of interests reported J: non-commercial K: no information

|

Inclusion criteria SR: RCT’s that recruited people who smoked prior to any surgery, who were offered a smoking cessation intervention. Measurements should include preoperative and long-term abstinence from smoking and/or the incidence of postoperative complications.

Exclusion criteria SR: No exclusion criteria reported

11 of 13 studies included

N, mean age A: 102, age unknown B: 168, 48 years C: 117, 55 years D: 120, 65 years (median) E: 237, 51 years F: 169, 52 years G: 244, 55 years (median) H: 130, 57 years (median) I: 46, 52.7 years J: 210, 43 years K: 286, 52 years

Sex: A: unknown B: 45% male C: 53% male D: 43% male E: 48% male F: 52% male G: 85% male H: no males I: 48% male J: 38% male K: 53% male

Cigarette consumption (mean/day) A: unknown B: 16 C: 15 D: 15 E: 12 F: 45% ≤10, 55% >10 G: 17 H: not reported I: 17 J: not reported K: 18

Study groups are largely comparable at baseline. Study of Thomsen (2010) only consist of females. |

A: Booklet and nurse advice + contact details for Stop Smoking Service and letter from the consultant (four weeks prior to surgery) stating that stopping smoking prior to surgy results in huge benefits. B: 5-minute counselling by a trained nurse, brochures on smoking cessation, referral to the Smoker’s Helpline, which contacted the participants up to four times and initiated subsequent counselling. Supply of transdermal nicotine replacement for 6 weeks. C: Weekly sessions with a trained smoking cessation counsellor (face-to-face or by telephone) + nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) 4 weeks pre- and 4 weeks postoperatively. D: Weekly meetings with smoking cessation counsellor, initiated 6-8 weeks prior to surgery and personalized nicotine replacement schedule. Strong advice to stop smoking, but also the option to reduce smoking by at least 50%. E: A 15-minute face-to-face counselling with a trained nurse 1-3 weeks before surgery. Supply of written materials, quit kit, nicotine gum and a hotline number. Postoperative counselling in the hospital and face-to-face. F: Brief advice and warning that exhaled carbon monoxide would be monitored on the morning of surgery. G: Standard advice + a face-to-face session in the clinic for 20 minutes with study nurse, 1 month before surgery, and NTR up to two hours before surgery. H: Brief counseling with a smoking cessation counsellor, 3-7 days before surgery and additional NRT. I: 2-minute session with the advice to stop smoking from 7:00 pm the night before surgery. Also advice to use a total of sixteen lozenges (nicotine 2 or 4 mg per lozenge, dependent on time of waking up) when the patients usually smokes, from 7:00 pm the night before surgery until surgery. J: Interactive counselling session, once for 17 minutes, 1-2 weeks before surgery + one telephone counseling and advice initiated by the nursing and anesthetic staff. NRT for dependent smokers. K: Varenicline, initiated one week before surgery and continued for 12 weeks. Titration schedule as follows: 0.5 mg once daily for day 1-3, 0.5 mg twice daily for day 4-7, 1 mg twice daily for weeks 2-12. Also, two 15-minute counselling sessions. |

A: Booklet and nurse advice B: Standard care (inconsistent smoking cessation advice from nurses, anaesthesiologists, or surgeons). C: Standard care D: Standard care E: Standard care F: Brief advice to stop smoking. G: Standard advice to stop smoking at least 1 month before surgery up to 10 days after surgery. H: Standard care with no or inconsistent advice about the risks of smoking before surgery. I: See intervention, placebo lozenges J: Standard care K: Placebo according to the schedule of the intervention and two additional 15-minute counselling sessions.

|

Endpoint of follow-up: A: unknown B: 12 months C: 12 months D: 1 year E: 12 months F: not reported G: 5-8 months H: 12 months I: not reported J: 3 months K: 12 months

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: 0/1 B: 5/6 C: 7/3 (12-month follow-up, no losses to 30-day follow-up) D: 4/8 + 11 patients from control group missing at 1-year follow-up E: 24/11 (6-month follow-up), 36/32 (12-month follow-up) F: 2/3 G: Unclear; total missing cases n = 26 H: 10/7 I: 0/0 J: 16/10 K: 17/16

|

Effect measure: RR, M-H, random, [95% CI]: RR>1.00 favours intervention

Smoking cessation (at surgery) Defined as self-reported point prevalence or continuous abstinence. A: 2.25 [1.08 to 4.70] B: 4.00 [1.17 to 13.66] C: 21.38 [2.97 to 153.72] D: 8.36 [3.19 to 21.86] E: 1.34 [.00 to 1.46] F: 0.94 [.80 to 1.11] G: 1.82 [0.79 to 4.18] H: 2.49 [1.10 to 5.60] I: 1.34 [0.86 to 2.1] J: 1.49 [0.98 to 2.26]

Pooled effect (of studies A, B, E, F, G, H, J 1.30 [1.16 to 1.46] Heterogeneity (I2): 75%

Smoking cessation (after 12 months) Defined as self-reported point prevalence or continuous abstinence. RR>1.00 favours intervention

C: 2.21 [1.1 to 4.44] D: 6.04 [1.43 to 25.48] E: 1.01 [0.6 to 1.7] H: 1.48 [0.5 to 4.38] K: 1.45 [1.01 to 2.07]

Complications Defined as any complication after surgery that required treatment. B: 0.79 [0.38 to 1.63] C: 0.51 [0.27 to 0.97] D: 0.34 [0.19 to 0.64] H: 1.00 [0.75 to 1.33] K: 0.94 [0.52 to 1.72]

Secondary surgery D: 2/56 (4%) vs. 8/52 (15%) H: 1/57 (2%) vs. 0 (0%)

Mortality Not reported by the studies included in the current review.

Length of hospital stay Median in days B: 1.75 (IQR: 1.1 to 3.1) vs. 2.1 (1.4 to 3.2) C: 1 (range: 1 to 10) vs. 1 (1 to 11) D: 11 (range: 7 to 55) vs. 13 (8 to 85) H: 2 (range 1 to 7) vs. 3 (1 to 8)

|

Facultative: The authors conclude that intensive interventions (investigated by Lindström (2008) and Møller, 2002)) are beneficial for changing smoking behaviour and reducing complications after surgery. Brief interventions are likely to have a small benefit on smoking behaviour, but a positive effect for complications was not found.

Number of patients in the control groups that stops smoking varies widely among studies. GRADE recommendations seem high with respect to the number of included participants. For risk-of-bias, blinding was judged adequate if only outcome assessors were blinded. Study of Wong (2012) excluded light smokers (<10 cig/day). Sørensen (2007) was included in the pooled analysis for any complications, although only wound infections have been measured. The study is therefore excluded for this outcome in the current literature review. Meta-analysis of smoking cessation includes only brief interventions of maximum a few weeks.

Level of evidence (GRADE)

HIGH Smoking cessation at time of surgery (intensive interventions)

MODERATE Smoking cessation at time of surgery (brief interventions) Downgraded one level for imprecision.

MODERATE Any complications after surgery (intensive interventions) Downgraded one level for imprecision.

MODERATE Any complications after surgery (brief interventions) Downgraded one level for imprecision.

No GRADE calculated for secondary surgery, mortality and length of hospital stay. |

|

Abbreviations: M-H: Mantel-Haenszel, NRT: nicotine replacement therapy, RCT: randomized controlled trial, RR: risk ratio, SR: systematic review |

|||||||

Evidence table for intervention studies.

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

||||||||||||||||

|

Wong, 2017 |

Type of study: Randomized controlled trial open-label

Country: Canada

Funding and conflicts of interest: Mostly non-commercial funding, with exception of research grant from Pfizer Inc. No further conflicts of interest reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Adult patients scheduled for elective ambulatory or inpatient surgery within the next week to two months. Patients needed to be current smoker with consumption of at least ten cigarettes/day with no abstinence of longer than three months in the past year.

Exclusion criteria: Current pregnancy and breastfeeding; major depression, panic disorder, psychosis or bipolar disorder within the previous year; use of nicotine replace-ment therapy (NRT) or bupropion within the previous three months. Patients with cardiovascular disease (eg, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, congestive heart failure, or moderate to severe valvular disease) within the past 6 months; a serious or un-stable disease within the past six months (eg, stroke, renal failure or insufficiency, hepatic failure, or uncontrolled hypertension); drug or alcohol abuse or dependence within the past year; and use of tobacco products other than cigarettes or marijuana use within the previous month. Patients with any form of cognitive impairment, participation in any other studies, inability to understand English, or lack of a telephone number to be reached for follow-up.

N total at baseline I: 151 C: 145

Important prognostic factors2: Sex (% male) I: 57.9% C: 66.9%

Mean age (SD) I: 51.4 (12.5) C: 52.3 (12.4)

Cigarette consumption (mean/day)(SD) I: 16.2 (7.1) C: 18.0 (7.7)

Groups largely comparable at baseline. |

Smoking cessation program with - A 10–15-minute preoperative counselling session - Pharmacotherapy with free supply of varenicline for three months. - Educational pamphlet - Fax referral to a quit line for proactive phone counselling and follow-up. |

Brief advice regarding smoking cessation and quit line information for self-referral. |

Length of follow-up: One year

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 15 (10.3%) Reasons: Discontinue of participation (n = 13), death (n = 1), not reachable (n = 1)

C: 20 (13.2%) Reasons: Discontinue of participation (n = 18 of which n = 1 after treatment), death (n = 1), not reachable (n = 1)

Incomplete outcome data: See ‘loss-to-follow-up’. |

Smoking abstinence 7-day point prevalence abstinence RR, [95%CI] Intervention vs. control

Continuous abstinence RR, [95%CI] Intervention vs. control

Postoperative complications Total I: 32 (22.4%) C: 39 (26.2%) |

Strict exclusion criteria, with light smokers excluded from the study. |

||||||||||||||||

|

Abbreviations: NRT: nicotine replacement therapy, OR: odds ratio, RR: risk ratio |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Risk of bias tables

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded? Were healthcare providers blinded? Were data collectors blinded? Were outcome assessors blinded? Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Andrews, 2006 |

Probably yes

Reason: Numbers drawn from opaque bag. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Numbers drawn from opaque bag. First number drawn out was assigned to intervention status. |

Definitely no

Reason: Open-label trial, no blinding of participants or personnel. Unclear for assessors of smoking status. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All participants from intervention group completed the study. One missing patient from control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Probably no

Reason: Baseline characteristics are not clearly described.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding, missing information on baseline characteristics. |

|

Lee, 2013 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer-generated block randomization. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes. |

Definitely no

Reason: Outcome assessors were blinded. Participants were not blinded. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Five patients of intervention group and six patients of control group were lost to follow-up. Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding |

|

Lindström 2008 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Stratified block randomization. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes. |

Definitely no

Reason: Only study physicians were blinded. No blinding of participants and further personnel. |

Probably yes

Reason: No losses to follow-up after 30 days. 7/48 intervention and 3/54 controls lost to follow-up after one year. Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding |

|

Møller, 2002 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Stratified block randomization. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes. |

Definitely no

Reason: Outcome assessors were blinded. Participants and further personnel were not blinded. |

Probably no

Reason: At 1-year follow-up, 11/52 patients from the control group were missing (vs no missing data from intervention group). Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding Attrition bias for missing data of intervention group. |

|

Ratner, 2004 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer-generated block randomization. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Sealed envelopes with computer-generated random allocation. |

Probably no

Reason: No blinding of participants, not stated whether personnel were blinded. |

Probably no

Reason: At 6-month follow-up, loss-to-follow-up was twice as high in the intervention group compared to the control group (24/117 vs. 11/120). Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding Attrition bias for missing data of intervention group. |

|

Shi, 2013 |

Probably yes

Reason: Stratified randomization, not stated who generated the randomization sequence. |

No information |

Definitely no

Reason: Participants and clinical personnel were not blinded. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Numbers and reasons for drop-out did not differ across interventions. Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: No information on allocation concealment. Risk of bias due to no blinding |

|

Sørensen, 2007 |

Probably yes

Reason: Computer generated randomization |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes. |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding of participants and personnel. |

Probably no

Reason: Unclear to what missing data differed between the intervention and control group. Total missing data of n = 26. Per-protocol analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

HIGH (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding Possible attrition bias, due to use of per protocol analysis. |

|

Thomsen, 2010 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Allocation sequence generated by a research secretary with no other involvement in the study. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes. |

Definitely no

Reason: Only outcome assessors were blinded. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Numbers and reasons for drop-out did not differ across interventions. Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding |

|

Warner, 2012 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer-generated stratified block randomization. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Packets according to strata of specific subject ID numbers. |

Probably yes

Reason: ‘Double-blind RCT’. No further information reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No dropouts. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Probably no

Reason: No information on eligible versus included participants, as no flow chart is available. |

LOW (all outcomes) |

|

Wolfenden, 2005 |

Probably yes

Reason: Computer generated randomization |

Probably yes

Reason: Web-based randomization |

Definitely no

Reason: Outcome assessors were blinded. Personnel and participants not blinded to group allocation. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Similar loss-to-follow-up in intervention group (12%) and control group (13%). Use of ITT analysis. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding. |

|

Wong, 2012 |

Probably yes

Reason: Computer generated randomization |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes, kept by an independent research pharmacist. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Participants, healthcare personnel and research staff were blinded. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Numbers and reasons for drop-out did not differ across interventions. Use of ITT analysis, except for outcome complications (per-protocol analysis). |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Probably no

Reason: No other problems noted. |

LOW (all outcomes except complications) Some concerns (complications)

Reason: Possible attrition bias, due to per-protocol analysis for the outcome complications

|

|

Wong, 2017 |

Definitely yes

Reason: Computer generated randomization, generated by a research analyst who was not involved in the study. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Use of opaque sealed envelopes. |

Definitely no

Reason: No blinding of participants and personnel. |

Definitely yes

Reason: Numbers and reasons for drop-out did not differ across interventions. Multiple imputation of missing data. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All outcomes that were prespecified in the article are reported. |

Definitely yes

Reason: No other problems noted.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes except mortality) LOW (mortality)

Reasons: Risk of bias due to no blinding. |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 06-10-2023

Laatst geautoriseerd : 06-10-2023

Geplande herbeoordeling :

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd door het Longfonds.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten die roken.

Samenstelling van de werkgroep

Werkgroep

- C.W.H.M. (Chantal) Kroese-Bovée, longarts, werkzaam in het Ikazia Ziekenhuis te Rotterdam, NVALT (voorzitter)

- P.C. (Pauline) Dekker, longarts, werkzaam in het Rode Kruis Ziekenhuis te Beverwijk, NVALT

- D. (Dirk) Nijmeijer, longarts, werkzaam in het Streekziekenhuis Koningin Beatrix Winterswijk te Winterswijk, NVALT

- E.M.T. (Eva) Bots, longarts, werkzaam in het Haaglanden Medisch Centrum te Den Haag, NVALT

- U.K. (Uclan) Flanders, longarts, werkzaam in het Elisabeth-TweeSteden Ziekenhuis te Tilburg, NVALT

- Dr. M.J. (Maurits) van Veen, cardioloog, werkzaam in Ziekenhuis Gelders Vallei te Ede, NVVC

- Dr. R. (Rinske) Loeffen, internist, werkzaam in het Maasstad Ziekenhuis te Rotterdam, NIV

- Dr. J. (Jolien) Tol, internist, werkzaam in het Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis te ‘s Hertogenbosch, NIV

- Dr. L.R.C.W. (Luc) van Lonkhuijzen, gynaecoloog oncoloog, werkzaam in het Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum te Amsterdam, NVOG

- Dr. M.A.J. (Marjolein) van Looij, KNO-arts, werkzaam in het Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis te Amsterdam, NVKNO

- Dr. M.A.M. (Maarten) Wildeman, KNO-arts, werkzaam in het Alrijne Ziekenhuis te Leiderdorp, NVKNO

- Dr. K.J. (Koen) Hartemink, chirurg, werkzaam in het Antoni van Leeuwenhoek te Amsterdam, NVvH

- Dr. J.M. (Jentien) Vermeulen, verslavingspsychiater (AIOS), werkzaam in het Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum te Amsterdam, NVVP

- E.S. (Ellen) Jacobs-Taag, verpleegkundig specialist, werkzaam in het Hagaziekenhuis te Zoetermeer, V&VN

- A.J.M. (Agnes) de Bruijn, senior adviseur Preventie, werkzaam bij het Longfonds te Amersfoort

- P.J. (Flip) Homburg, ervaringsdeskundige, vrijwilliger bij het Longfonds te Amersfoort

- J. E. (Hanneke) Schaap - Tuinier, werkzaam in het Ikazia Ziekenhuis te Rotterdam, V&VN (tot februari 2022)

Klankbordgroep

- R. (Roel) van Vugt, anesthesioloog, werkzaam bij de Sint Maartenskliniek te Nijmegen, NVA

- Dr. M.H. (Heleen) den Hertog, neuroloog, werkzaam bij het Isala te Zwolle, NVN

- Dr. A. (Annemarieke) de Jonghe, geriater, werkzaam bij Tergooi Medisch Centrum te Hilversum, NVKG

Met ondersteuning van:

- Dr. B.H. (Bernardine) Stegeman, senior adviseur, werkzaam bij het Kennisinstituut van Federatie Medisch Specialisten te Utrecht.

- J.M.H. (Harm-Jan) van der Hart (vanaf 1 oktober 2022), MSc, junior adviseur, werkzaam bij het Kennisinstituut van Federatie Medisch Specialisten te Utrecht.

- Dr. N. (Nicole) Verheijen (tot 1 oktober 2022), senior adviseur, werkzaam bij het Kennisinstituut van Federatie Medisch Specialisten te Utrecht.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Onderno-men actie |

|

C.W.H.M. Kroese-Bovée |

Longarts, Ikazia Ziekenhuis |

Visitatie commissie NVALT (betaald). Lid van Partnership Stoppen met Roken. Caspir training in regio Zuid Holland West, als longarts (betaald). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

P.C. Dekker |

Longarts, Roze Kruis Ziekenhuis |

Lid Stichting Rookpreventie jeugd (onbetaald). Lid van het Partnership stoppen met roken. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

D. Nijmeijer |

Longarts Streekziekenhuis Koningin Beatrix Winterswijk |

In het verleden Caspir training gegeven. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

E.M.T. Bots |

Longarts Haaglanden Medisch Centrum |

Lid AIOS bestuur NVALT t/m mei 2021. Werkzaamheden: concilium, beleidscommissie, jonge klare database (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

U.K. Flanders |

Longarts, Elisabeth-Tweesteden Ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. M.J. van Veen |

Cardioloog, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei |

Bestuurslid Commissie Kwaliteit NVVC, Bestuurslid Partnership Stoppen met Roken (vergoeding middels vacatiegelden). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. R. Loeffen |

Internist, Maasstad Ziekenhuis |

Redactielid Focus Vasculair (onbetaald), lid werkgroep perifeer vaatlijden. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. J. Tol |

Internist Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis |

lid NVMO-commissie BOM (beoordeling oncologische middelen), vergoeding middels vacatiegelden. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. L.R.C.W. van Lonkhuijzen |

Gynaecoloog oncoloog, Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. M.A.J. van Looij |

KNO-arts Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis |

Ruggespraak arts (2e arts online tot 2022, betaald), bestuurslid SVNL (Slaapvereniging NL, onbetaald), voorzitter bestuur commissie kwaliteit en accreditatie SVNL (onbetaald), lid werkgroep revisie richtlijn pediatrisch OSAS (vacatiegelden), lidmaatschap van commissie PrevENT van de NVKNO (vacatiegelden), lid richtlijnen commissie van ESRS (Europese Sleep Research Society, onbetaald), adviserend arts DEKRA (betaald). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. M.A.M. Wildeman |

KNO-arts, Alrijne Ziekenhuis |

Commissie lid PrevENT, werkzaamheden teamverband oude promotie voor mogelijk nieuwe onderzoeks-project voor vroeg detectie op kankergebied in Indonesië en Zuid-Afrika. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. K.J. Hartemink |

Chirurg, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek |

Faculty NVALT "Oncologie voor de longarts, Specialisten adviesraad, Longkanker Nederland, Commissielid Wetenschap DLCA-S, Bestuurslid DLCRG. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. J.M. Vermeulen |

Verslavingspsychiater, Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum |

Redactie Handboek Leefstijlpsychiatrie (onbetaald). Bestuurslid Verslavingspsychiatrie NVvP. (onbetaald) Bestuurslid De Jonge Psychiater (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

E.S. Jacobs-Taag |

Verpleegkundig specialist, Hagaziekenhuis Zoetermeer |

IMIS trainer (betaald), Coordinator longzorg bij zorggroep Hadoks |

Geen |

Geen |

|

A.J.M. de Bruijn |

Senior adviseur Preventie, Longfonds |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

P.J. Homburg |

Ervaringsdeskundige, Longfonds |

voorzitter Regioteam/ Longpunt Zeeland Longfonds, vertrouwenspersoon CNV ten behoeve van leden die behoefte aan ondersteuning na 1 jaar ziekte en keuringen door UWV, workshopgever voor leden CNV Connectief (onbetaald), lid patientenadviesraad Longen van het Franciscus ZH en Erasmus MC. |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. B.H. Stegeman |

Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

J.M.H. van der Hart |

Junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. N. Verheijen |

Senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Klankbord-groeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Drs. R. van Vugt |

Anesthesioloog, Sint Maartenskliniek |

Lid commissie kwaliteitsdocumenten (CKd) NVA (onbetaald), lid stuurgroep cluster epilepsie, Kennisinstituut FMS (onbetaald), DARA-instructeur, locoregionaal anesthesie cursus (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. M.H. den Hertog |

Neuroloog, Isala |

Lid commissie CVRM (onbetaald), voorzitter Neurovasculaire werkgroep (onbetaald), lid werkgroep elearning acute neurologie (onbetaald), lid werkgroep visie cardiovasculaire zorg (onbetaald), medical board speerpunt acute zorg Isala (onbetaald), spreker nascholingen Prevents (betaald) en BENEFIT consortium (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen |

|

Dr. A. de Jonghe |

Geriater, Tergooi Medisch Centrum |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door deelname van het Longfonds in de werkgroep. Resultaten van een door het Longfonds uitgezette enquête onder patiënten, zijn verwerkt in de module Begeleiding van stoppen met roken na ontslag. De verkregen input is ook meegenomen bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan het Longfonds. De eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Stoppen met roken bij psychiatrische patiënten |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module Nicotine vervangende therapie tijdens opname |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module Perioperatief traject |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

|

Module Begeleiding van stoppen met roken na ontslag |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Het overgrote deel voldoet aan de norm. |

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die roken. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de IGJ, NHG, NOG, NOV, NVK, NVKNO, NVOG, NVR, NVRO, NVSHA, NVVC, NVvP, V&VN, VRA, ZiNL en het Trimbos Instituut via een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten (Bijlage 2).

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Begeleiding van stoppen met roken na ontslag.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/uploaded/docs/Medisch_specialistische_richtlijnen_2-0_-_tot_2023_-_verouderd.pdf?u=1aYjPr.

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.