Operatieve versus niet-operatieve behandeling

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van rotator cuff repair in vergelijking met oefen-/fysiotherapie (met of zonder een corticosteroïdeninjectie) bij patiënten met een geïsoleerde degeneratieve supraspinatuspeesruptuur?

Aanbeveling

Schrijf bij patiënten met SAPS-klachten en een geïsoleerde, symptomatische en niet-traumatische supraspinatusruptuur als eerste een conservatieve behandeling voor (i.e. oefentherapie gegeven door een oefen- of fysiotherapeut met affiniteit voor de behandeling van schouderklachten, eventueel in combinatie met een corticosteroïdeninjectie).

Overweeg een operatie (rotator cuff repair) indien adequate conservatieve behandeling na 3-6 maanden niet succesvol is (i.e. oefentherapie gegeven door een oefen- of fysiotherapeut met affiniteit voor de behandeling van schouderklachten, eventueel in combinatie met een corticosteroïdeninjectie).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar het effect van een operatie waarbij de rotator cuff wordt gehecht in vergelijking met oefen-/fysiotherapeutische behandeling (met of zonder een corticosteroïdeninjectie) in volwassenen (<70 jaar) met een niet-traumatische geïsoleerde ruptuur van de supraspinatuspees. Er zijn vier studies geïncludeerd die zijn beschreven in acht publicaties.

Op basis van de literatuuranalyse konden geen conclusies worden getrokken over het effect van een operatie waarbij de rotator cuff wordt gehecht op de uitkomstmaten functie, pijn, kwaliteit van leven, terugkeer naar werk en vrijetijdsbestedingen, en complicaties, vergeleken met oefen-/fysiotherapeutische behandeling (met of zonder een corticosteroïdeninjectie) in volwassenen (<70 jaar) met een niet-traumatische geïsoleerde ruptuur van de supraspinatuspees. De bewijskracht voor de cruciale en belangrijke uitkomstmaten is zeer laag. Dit wordt met name veroorzaakt doordat in één studie (Moosmayer, 2019) de helft van de patiënten een traumatische scheur had (indirectheid van de patiëntenpopulatie), het risico op vertekening (bias) en het kleine aantal geïncludeerde patiënten. Hier ligt dan ook een kennisvraag. De keuze voor de ene dan wel de andere behandeling zal dan ook afhangen van andere factoren.

Eén studie rapporteerde re-rupturen na operatieve behandeling en toename van de grootte van de scheur bij conservatief behandelde patiënten en de invloed hiervan op de uitkomst. In de operatieve groep kwamen full thickness re-rupturen na tien jaar bij 23% van de patiënten voor. Dit beïnvloedde de functionele uitkomst niet. Bij 40% van de patiënten die conservatief behandeld werden, was de toename van de scheur meer dan 10 mm, wat tot significant slechtere functionele uitkomsten leidde. In de geïncludeerde studie met tien jaar follow-up worden geen gegevens gedeeld over het ontwikkelen van degeneratieve afwijkingen glenohumoraal in beide groepen. Er werden geen prognostische factoren voor toename van scheur grootte geïdentificeerd bij patiënten die conservatief behandeld werden. Dit bemoeilijkt de keuze voor conservatieve of operatieve behandeling bij de start van behandeling. Een andere geïncludeerde studie vergeleek de uitkomsten van de intacte repair met conservatief behandelde patiënten. In een kleine groep met intacte repair was de uitkomst beter dan de conservatief behandelde groep. De bewijskracht voor deze uitkomsten was echter zeer laag.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is het belangrijk om de behandeling te krijgen die voor hen het meest passend is. Het is voor patiënten belangrijk dat zij worden meegenomen in het (mogelijke) behandeltraject zodat zij weten wat ze kunnen verwachten. Indien door de huisarts reeds een echografie is gemaakt en een cuff ruptuur met volledige dikte scheur is geconstateerd, wordt de patiënt (conform de NHG standaard) ter beoordeling naar de orthopedie verwezen. Bij mensen met langer bestaande SAPS-klachten en een niet-traumatische geïsoleerde supraspinatusruptuur bestaat bij patiënten vaak een overtuiging dat operatief herstel van de pees beter is. Dit komt mede doordat patiënten vaak al behandeld zijn door een oefen-/fysiotherapeut met onvoldoende succes. Daarnaast overzien patiënten het lange revalidatieproces na een cuff repair over het algemeen niet en hebben zij geen kennis van de uitkomst van conservatieve behandeling van geisoleerde supraspinatuspeesrupturen.

Fysiotherapie/oefentherapie eventueel in combinatie met een corticosteroïdeninjectie kan snel ingezet worden om de klachten te verlichten. Een operatie is niet alleen een veel meer belastende behandeling met risico’s, maar zal ten eerste niet direct uitgevoerd kunnen worden en kent ten tweede een lange revalidatietijd met ondersteuning van oefen-/fysiotherapie. Tijdens de genezingsfase van de pees na een operatieve ingreep moet een periode van meerdere weken een sling gedragen worden om de peeshechting te ontzien en mag patiënt de arm niet belasten. Mantelzorg of hulp thuis is de eerste weken nodig. Activiteiten zoals fietsen en autorijden zijn meerdere weken niet toegestaan en niet wenselijk.

Conservatieve behandeling van geïsoleerde supraspinatuspeesrupturen is bij driekwart van de patiënten effectief (Kuhn, 2013; Moosmayer, 2019). Ook zijn er aanwijzingen dat na conservatieve behandeling een operatie tot meer dan een jaar uitstellen tot minder goede uitkomsten leidt dan drie tot zes maanden uitstellen (Lu, 2023). Bij de overweging om conservatief te behandelen dan wel te opereren, dienen ook patiënt specifieke factoren overwogen te worden, zoals type werkzaamheden en sport. Een belangrijke factor die meegenomen moet worden in de beslissing tot een operatie of conservatief beleid is de leeftijd van patiënt. Bij toenemende leeftijd neemt de kans op een re-ruptuur na een operatie toe (Lambers Heerspink, 2014). De kans op progressie van een cuff ruptuur wordt door natuurlijk beloop bij oplopende leeftijd groter. Afhankelijk van de grootte, betrokkenheid van de rotator cable en de ontstaanswijze kan dit leiden tot een ruptuur waarvoor een eenvoudige reparatie niet meer mogelijk is (Keener, 2019). Daarom kan dit een reden zijn om op jongere leeftijd (bijvoorbeeld in de werkzame leeftijd) toch te besluiten tot een operatie.

Het is voor patiënten dus belangrijk dat zij bij de beslissing om conservatief te behandelen dan wel te opereren de voor- en nadelen van beide behandelingen, maar ook het revalidatieproces, verwachte revalidatietijd en verwachte uitkomst goed kunnen afwegen, zodat zij op basis van de principes van Samen Beslissen een keuze kunnen maken.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Conservatieve behandeling bestaat uit één of meerdere corticosteroïdeninjecties. De kosten hiervan zijn zeer beperkt in vergelijking met een operatie. Fysiotherapie/oefentherapie is gedurende de eerste twee maanden over het algemeen tweemaal per week nodig. Daarna neemt de intensiteit van de behandeling af en zal patiënt zelf moeten oefenen. In het hersteltraject is naar ervaring van de werkgroep over het algemeen zes tot negen maanden oefen-/fysiotherapie nodig.

Een operatieve behandeling brengt kosten met zich mee door de opname van de patiënt en materiaal gebruik peroperatief. Daarnaast kunnen patiënten door een periode immobilisatie niet werken en is over het algemeen postoperatief oefen-/fysiotherapie nodig gedurende zes maanden. Er zijn geen vergelijkende kosteneffectiviteitsstudies, maar het lijkt voor de hand te liggen dat de kosten van een operatieve behandeling hoger zijn dan van conservatieve behandeling.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Fysiotherapie/oefentherapie voor schouderklachten is een gangbare behandeling. Afzien van een operatie is aan patiënten goed uit te leggen, gezien de grote succeskans van conservatieve behandeling en de nadelige effecten van operatieve behandeling (te weten langdurige revalidatie en tijdelijke sociale beperkingen). Doordat veel patiënten al bij een oefen-/fysiotherapeut zijn geweest, is de acceptatie van conservatieve behandeling mogelijk minder. Hier is mogelijk een plek voor een fysiotherapeut die gespecialiseerd is in behandeling van schouderaandoeningen. Ook zal er een groep blijven die ondanks conservatieve behandeling klachten blijft houden. De werkgroep adviseert dan ook bij implementatie van conservatief beleid om patiënten drie maanden na start van conservatieve behandeling te controleren. Indien conservatieve behandeling onvoldoende effectief is, kan nadere diagnostiek (zie module Beeldvormende technieken) en operatieve behandeling overwogen worden. Het afwegen van belangrijke prognostische factoren is hierbij noodzakelijk (zie module Prognostische factoren).

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Overwegende het succespercentage van conservatieve behandeling, dat er op korte en middellange termijn geen verschil wordt gevonden tussen conservatieve en operatieve behandeling, dat de kosten van conservatieve behandeling lager zijn dan van operatieve behandeling, en dat na drie maanden conservatieve behandeling een operatieve behandeling nog goed mogelijk is, adviseert de werkgroep conservatieve therapie bij patiënten <70 jaar en >70 jaar met een geïsoleerde, symptomatische en niet-traumatische supraspinatusruptuur. De conclusie met betrekking tot patiënten <70 jaar is gesteld op basis van de literatuuranalyse; voor patiënten >70 jaar is deze gesteld op basis van expert opinie.

Deze behandeling bestaat uit oefentherapie (gegeven door een oefen- of fysiotherapeut), eventueel in combinatie met een corticosteroïdeninjectie. Patiënten dienen geïnformeerd te worden over de kans op toename van de scheur in de toekomst bij conservatieve behandeling. De werkgroep adviseert om patiënten op te volgen na conservatieve behandeling. Als na adequate conservatieve behandeling na drie tot zes maanden geen verbetering optreedt, kan rotator cuff repair overwogen worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

A rotator cuff tear is common but does not always require surgery. A distinction needs to be made between traumatic and non-traumatic changes. Additionally, there is a difference in location and extent of degenerative cuff ruptures. It is known that subscapularis tendon ruptures are important for shoulder stability and the functioning of the long biceps tendon. Subscapularis tendon ruptures generally occur due to trauma (Ghasemi, 2023). Other traumatic rotator cuff ruptures, for example, after an anterior shoulder dislocation with good tissue quality, may indicate a need for surgical repair. In case of multi tendon tear a partial rotator cuff repair or tendon transfer can be a good indication to restore range of motion. For these reasons, traumatic and multi tendon tears are excluded from this research question. The indication and success of the repair of a non-traumatic supraspinatus tendon rupture depends on many factors (Lambers Heerspink, 2014). Together, a decision must be made whether surgery is beneficial or not.

Conclusies

Function

Constant Murley Score (CMS)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of rotator cuff repair on function as measured with the Constant Murley Score at 1, 2, 5 or 10 years follow-up when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated non-traumatic, rupture of the supraspinatus tendon.

Source: Kukkonen, Lambers Heerspink, Moosmayer |

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of rotator cuff repair on function as measured with the DASH when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. |

The Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of rotator cuff repair on function as measured with the WORC when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. |

American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of rotator cuff repair function as measured with the ASES at 1, 2, 5 or 10 years follow-up when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated non-traumatic rupture of the supraspinatus tendon.

Source: Moosmayer |

Dutch Simple Shoulder Test (DSST)

1-year follow-up

|

Low GRADE |

Rotator cuff repair may result in little to no difference in function as measured with the DSST at 1 year follow-up when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon.

Source: Lambers Heerspink |

2, 5 and 10-year follow-up

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of rotator cuff repair on function as measured with the DSST at 2, 5 and 10 years follow-up when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. |

Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of rotator cuff repair on function as measured with the OSS when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. |

Pain

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of rotator cuff repair on pain 1, 2, 5 or 10 years postoperatively when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated nontraumatic rupture of the supraspinatus tendon.

Source: Kukkonen, Lambers Heerspink, Moosmayer |

Patient satisfaction

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of rotator cuff repair on patient satisfaction when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon.

Source: Kukkonen, Moosmayer |

Complications

Re-rupture

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of rotator cuff repair on patient re-rupture when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon.

Source: Moosmayer |

Frozen shoulder and infection

|

No GRADE |

No adverse events were reported in the included studies considering the outcome measures frozen shoulder and infection. |

Return to work or leisure

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of rotator cuff repair on return to work or leisure when compared with physiotherapy (with or without injection of corticosteroids) in adult patients with an isolated rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

An overview of characteristics of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Results

- PROMS – Function

Constant Murley Score (CMS)

1-year follow-up

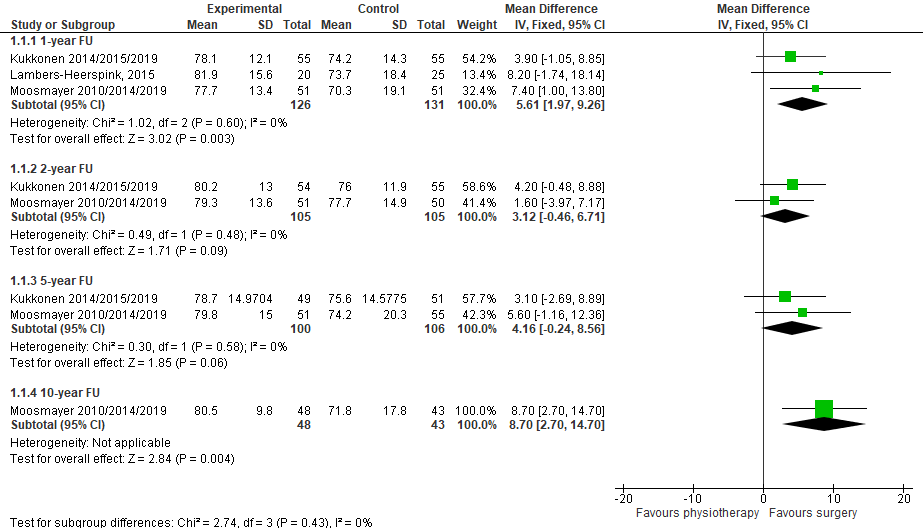

Three studies reported the 1-year follow-up using the Constant-Murley score (CMS)(Figure 1). This scale ranges from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates a better function.

The mean difference (MD) for Kukkonen et al. was 3.90 (95% CI -1.05 to 8.85).

The MD for Lambers Heerspink (2015) was 8.20 (95% CI -1.74 to 18.14).

The MD for Moosmayer et al. was 7.40 (95% CI 1.00 to 13.80).

The pooled MD was 5.61 (95% CI 1.97 to 9.26), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

2-year follow-up

Three studies reported the 2-year follow-up using the CMS (Figure 1). This scale ranges from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates a better function.

Two studies reported the absolute values at time of follow-up.

The MD for Kukkonen et al. was 4.20 (95% CI -0.48 to 8.88).

The MD for Moosmayer et al. was 1.60 (95% CI -3.97 to 7.17).

The pooled MD was 3.12 (95% CI -0.46 to 6.71), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

Cederqvist (2021) reported the change in CMS score from baseline to 2-year follow-up. The change was +20.0 (SD 16.18) in the intervention group and +13.0 (SD 16.18) in the control group. The MD was 7.00 (95% CI 1.99 to 12.01), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

5-year follow-up

Two studies reported the 5-year follow-up using the CMS (Figure 1). This scale ranges from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates a better function.

The MD for Kukkonen et al. was 3.10 (95% CI -2.69 to 8.89).

The MD for Moosmayer et al. was 5.60 (95% CI -1.16 to 12.36).

The pooled MD was 4.16 (95% CI -0.24 to 8.56), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

10-year follow-up

One study reported the 10-year follow-up using the CMS (Figure 1) and ASES. These scales range from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates a better function.

Moosmayer et al. reported that the CMS score after primary tendon repair was 80.5 (SD 9.8) in the intervention group and 71.8 (SD 17.8) in the control group. The MD was 8.70 (95% CI 2.70 to 14.70), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

After secondary surgery, the mean Constant scores increased by 33.9 points (SD 19.7), which is less than that achieved in the primary surgery group (41.4 points). The MD was 7.5 (95% CI 0.9 to 19.2) in favor of surgery (Moosmayer, 2019). This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. The effect of rotator cuff repair surgery on function, measured with the Constant Murley Score

Abbreviations: FU, follow-up.

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)

No study reported the DASH.

The Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC)

No study reported the WORC.

American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES)

1-year follow-up

Moosmayer et al. also reported the American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score. This score ranges from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates a better function. The ASES score was 93.6 (SD 12.5) in the intervention group and 83.6 (SD 18.3) in the control group. The MD was 10.00 (95% CI 3.92 to 16.08) in favor of surgery. This difference is considered to be clinically relevant.

2-year follow-up

Moosmayer et al. also reported the ASES score. The ASES score was 93.1 (SD 13.9) in the intervention group and 88.0 (SD 14.9) in the control group. The MD was 5.10 (95% CI -0.52 to 10.72), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

5-year follow-up

Moosmayer et al. also reported the ASES score. The ASES score was 92.8 (SD 13.3) in the intervention group and 85.4 (SD 21.0) in the control group. The MD was 7.40 (95% CI 0.76 to 14.04), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

10-year follow-up

Moosmayer et al. reported that the ASES score was 94.0 (SD 9.5) in the intervention group and 80.0 (SD 20.2) in the control group. The MD was 14.00 (95% CI 7.39 to 20.61), in favor of surgery. This difference is considered to be clinically relevant.

Dutch Simple Shoulder Test (DSST)

1-year follow-up

Lambers Heerspink (2015) reported the Dutch Simple Shoulder Test (DSST) scores. This score ranges from 0 to 100 and a higher score indicates a better function. The DSST score was 11.0 (SD 2.8) in the intervention group and 9.7 (SD 3.6) in the control group. The MD was 1.30 (95% CI -1.35 to 3.95), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

2, 5 and 10-year follow-up

No studies reported the DSST at 2, 5 and 10 years follow-up.

Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS)

No study reported the OSS.

- Pain

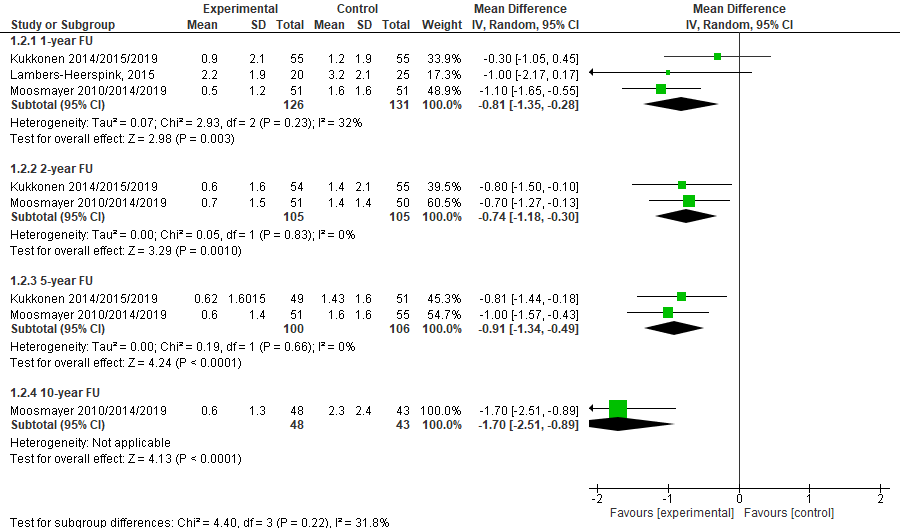

1- year follow-up

Three studies reported the 1-year follow-up using the VAS score. This scale ranges from 0 to 10 and a higher score indicates more pain.

The MD for Kukkonen et al. was -0.30 (95% CI -1.05 to 0.45).

The MD for Lambers Heerspink (2015) was -1.00 (95% CI -2.17, 0.17).

The MD for Moosmayer et al. was -1.10 (95% CI -1.65, -0.55).

The pooled MD was -0.81 (95% CI -1.35 to -0.28; figure 2), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

2 years follow-up

Three studies reported the 2-year follow-up using the VAS score. This scale ranges from 0 to 10 and a higher score indicates more pain.

Two studies reported the absolute values at time of follow-up.

The MD for Kukkonen et al. was -0.80 (95% CI -1.50, -0.10).

The MD for Moosmayer et al. was -0.70 (95% CI -1.27, -0.13).

The pooled MD was -0.74 (95% CI -1.18 to -0.30; figure 2), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

Cederqvist (2021) reported the change in pain score from baseline to 2-year follow-up on a 0-100 VAS scale. The change score was -37.0 (SD 26.96) in the intervention group and -24.0 (SD 26.96) in the control group. The MD was 13.00 (95% CI -4.64 to 21.36), in favor of surgery. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

5 years follow-up

Two studies reported the 5-year follow-up using the VAS score. This scale ranges from 0 to 10 and a higher score indicates more pain.

The MD for Kukkonen et al. was -0.81 (95% CI -1.44, -0.18).

The MD for Moosmayer et al. was -1.00 (95% CI -1.57, -0.43).

The pooled MD was -0.91 (95% CI -1.34, -0.49; figure 2), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered clinically relevant.

10 years follow-up

One study reported the 10-year follow-up using the VAS score. This scale ranges from 0 to 10 and a higher score indicates more pain. Moosmayer et al. reported that the VAS score was 0.6 (SD 1.3) in the intervention group and 2.3 (SD 2.4) in the control group. The MD was -1.70 (95% CI -2.51 to -0.89; figure 2), in favor of surgery. This difference is considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 2. The effect of rotator cuff repair surgery on pain

- Patient satisfaction

Three studies reported about patient satisfaction.

Kukkonen et al. reported the percentage of patients that were satisfied with the treatment outcome.

At 1-year follow-up, 95% of the intervention group and 87% of the control group were satisfied with the treatment outcome (difference of 7%).

At 2-year follow-up, 94% of the intervention group and 89% of the control group were satisfied with the treatment outcome (difference of 5%).

At 10-year follow-up, 92% of the intervention group and 88% of the control group were satisfied with the treatment outcome (difference of 4%).

These differences are in favor of surgery, but are not considered to be clinically relevant.

Moosmayer et al. reported patient satisfaction as measures on a VAS scale ranging from 0 to 10 with a higher score indicating more satisfaction.

At 1-year follow-up, the VAS score was 9.0 (SD 28.4) in the intervention group and 7.2 (SD 25.6) in the control group. The MD was 1.80 [-8.70, 12.30), in favor of surgery. This difference is considered to be clinically relevant.

At 5-year follow-up, the VAS score was 9.2 (SD or CI not reported) in the intervention group and 8.3 (SD or CI not reported) in the control group. The MD was 1.0 cm (95% CI 0.1 to 1.8), in favor of surgery. This difference is considered to be clinically relevant.

At 10-year follow-up, the VAS score was 9.2 (SD or CI not reported) in the intervention group and 8.2 (SD or CI not reported) in the control group. The MD was 0.97 cm (95% CI 0.13 to 1.82), in favor of surgery. This difference is not considered to be clinically relevant.

- Complications/adverse events

Moosmayer (2019) reported tear size for 32 patients treated by physiotherapy only (assessed with sonographic tear size measurement at baseline and at 5- and 10-year follow-up), and for 47 patients who were treated by primary repair (assessed with MRI after one year and by sonography after 5 and 10 years). In the physiotherapy group (n=32), tear size increased from baseline to 10-year follow-up with 10.1 mm (95% CI 5.7 to 14.4) in the anterior-posterior plane and with 6.3 mm (95% CI 2.9 to 9.8) in the medial-lateral plane. A total of 19 patients (59%) had an increase of tear size greater than 5 mm, and 13 patients (41%) had an increase of tear size of >10 mm. Patients with tears with widening of >10 mm had a Constant score of 63.9 points, an outcome that was inferior by 14.0 points (95% CI, 4.1 to 24.0 points; p = 0.007) compared with the score of 78 points in patients with tears with widening of <10mm. These quantitative findings however do not represent a comparison between the physiotherapy and primary repair groups and therefore clinically relevance is not stated.

In the primary repair group (n=47), an increasing number of full or partial thickness retears was found: 10 (21%) after one year, 13 (28%) after 5 years, and 16 (34%) after 10 years.

Cederqvist (2021) reported that no patients required re-operation and no serious adverse events were noted. Kukkonen et al. reported that no treatment-related complications occurred in any group. Lambers Heerspink et al. did not report about the occurrence of complications.

5. Return to work or leisure

Not reported.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence started at high, as included studies were RCTs.

- PROMS – Function

Constant Murley Score (CMS)

1-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the CMS at 1 year follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE, because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

1-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the CMS at 2 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

5-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the CMS at 5 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

10-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the CMS at 10 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (-1; imprecision).

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)

No studies were found that reported the DASH. Therefore, the level of evidence for this outcome measure could not be assessed.

The Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC)

No studies were found that reported the WORC. Therefore, te level of evidence for this outcome measure could not be assessed.

American Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES)

1-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the ASES at 1 year follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE, because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (-1; imprecision).

2-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the ASES at 2 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (-1; imprecision).

5-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the ASES at 5 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (-1; imprecision).

10-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the ASES at 10 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper threshold for clinical relevance (-1; imprecision).

Dutch Simple Shoulder Test (DSST)

1-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure function, measured with the DSST at 1 year follow-up, was downgraded by two levels to a low GRADE, because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

2, 5 and 10-year follow-up

No studies were found that reported the DSST at 2, 5 and 10 years follow-up. Therefore, te level of evidence for this outcome measure could not be assessed.

Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS)

No studies were found that reported the OSS. Therefore, te level of evidence for this outcome measure could not be assessed.

- Pain

1-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain, measured on a 0-10 VAS-scale at 1 year follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

2-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain, measured on a 0-10 VAS-scale at 2 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

5-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain, measured on a 0-10 VAS-scale at 5 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

10-year follow-up

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pain, measured on a 0-10 VAS-scale at 10 years follow-up, was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

- Patient satisfaction

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure patient satisfaction was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), conflicting results (-1; inconsistency), and a small number of included patients (-1; imprecision).

- Complications/adverse events

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure re-rupture was downgraded by three levels to a very low GRADE because of applicability of the results due to the inclusion of traumatic tears in Moosmayer et al. (-1, bias due to indirectness), and a very small number of included patients (-2, imprecision).

No study reported frozen shoulder or infection as adverse events. Therefore, the level of evidence for these outcome measures could not be assessed.

5. Return to work or leisure

No study reported return to work or leisure. Therefore, the level of evidence for these outcome measure could not be assessed.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectivity of cuff repair compared with physiotherapy with or without corticosteroid injection on patient-reported outcome measures in adult patients (<70 years) with an isolated symptomatic, nontraumatic, supraspinatus tear?

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and function as critical outcome measures for decision making; and patient satisfaction, complications/adverse events, and return to work or leisure as important outcome measures for decision making.

Results with a follow-up of 1 year and longer were considered relevant and were included in the literature summary.

The guideline development group defined the outcome measures as follows:

- Patient reported outcomes measures for function: CMS, DASH, WORC, ASES, DSST, OSS

- Pain: VAS-scale (0-10 points or 0-100mm scale)

- Complications/adverse events: re-rupture, frozen shoulder and infection

- Patient satisfaction: self-reported satisfaction with treatment and/or function

- Return to work or leisure: definitions used in the studies.

The guideline development group defined the minimal clinically (patient) important differences as follows:

- Patient reported outcome measures:

- CMS: 15 points on a 100-point scale (Holmgren, 2014)

- DASH: 13 on a 100 point scale (Koorevaar, 2018)

- WORC: -282.6 on a 2100 point scale (Gagnier, 2018)

- ASES: 9 on a 100 point scale (Gagnier, 2018)

- DSST: 2.8 on a 12 point scale (Van Kampen, 2013)

- OSS: 5 points on a 48-point scale (Nyring, 2021)

- Pain

- 1/10 points or 10/100 points on a VAS scale

- Complications/adverse events:

- Re-rupture: 5 mm difference in rupture size

- Frozen shoulder: 25% (RR ≤ 0.80 and ≥ 1.25)

- Infection: 25% (RR ≤ 0.80 and ≥ 1.25)

- Patient satisfaction: difference of 25% (RR ≤ 0.80 and ≥ 1.25) or 1/10 points or 10/100 points on a VAS scale.

- Return to work or leisure: difference of 25% (RR ≤ 0.80 and ≥ 1.25)

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until February 15, 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 431 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: 1) systematic review, meta-analysis or RCT 2) comparing rotator cuff repair surgery with physiotherapy alone or combined with corticosteroid injection 3) in adult patients aged 70 or younger 4) with an isolated symptomatic, nontraumatic, supraspinatus tear 5) reporting outcomes for pain, complications, PROMS and patient satisfaction 6) with a follow-up of 1 year and longer. Forty studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 32 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and eight publications reporting about four primary studies were included.

Results

Eight publications describing four studies and their follow-up were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Cederqvist S, Flinkkilä T, Sormaala M, Ylinen J, Kautiainen H, Irmola T, Lehtokangas H, Liukkonen J, Pamilo K, Ridanpää T, Sirniö K, Leppilahti J, Kiviranta I, Paloneva J. Non-surgical and surgical treatments for rotator cuff disease: a pragmatic randomised clinical trial with 2-year follow-up after initial rehabilitation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jun;80(6):796-802. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219099. Epub 2020 Dec 3. PMID: 33272959; PMCID: PMC8142425.

- Gagnier JJ, Robbins C, Bedi A, Carpenter JE, Miller BS. Establishing minimally important differences for the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score and the Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index in patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 May;27(5):e160-e166. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.10.042. Epub 2018 Jan 4. PMID: 29307675.

- Ghasemi SA, McCahon JAS, Yoo JC, Toussaint B, McFarland EG, Bartolozzi AR, Raphael JS, Kelly JD. Subscapularis tear classification implications regarding treatment and outcomes: consensus decision-making. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2023 Jan 10;3(2):201-208. doi: 10.1016/j.xrrt.2022.12.004. PMID: 37588429; PMCID: PMC10426670.

- Holmgren T, Oberg B, Adolfsson L, Björnsson Hallgren H, Johansson K. Minimal important changes in the Constant-Murley score in patients with subacromial pain. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014 Aug;23(8):1083-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.01.014. Epub 2014 Apr 13. PMID: 24726486.

- van Kampen DA, Willems WJ, van Beers LW, Castelein RM, Scholtes VA, Terwee CB. Determination and comparison of the smallest detectable change (SDC) and the minimal important change (MIC) of four-shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). J Orthop Surg Res. 2013 Nov 14;8:40. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-8-40. PMID: 24225254; PMCID: PMC3842665.

- Keener JD, Patterson BM, Orvets N, Chamberlain AM. Degenerative Rotator Cuff Tears: Refining Surgical Indications Based on Natural History Data. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019 Mar 1;27(5):156-165. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00480. PMID: 30335631; PMCID: PMC6389433.

- Koorevaar RCT, Kleinlugtenbelt YV, Landman EBM, van 't Riet E, Bulstra SK. Psychological symptoms and the MCID of the DASH score in shoulder surgery. J Orthop Surg Res. 2018 Oct 4;13(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-0949-0. PMID: 30286775; PMCID: PMC6172756.

- Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Mattila KT, Tuominen EK, Kauko T, Aärimaa V. Treatment of non-traumatic rotator cuff tears: A randomised controlled trial with one-year clinical results. Bone Joint J. 2014 Jan;96-B(1):75-81. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B1.32168. PMID: 24395315.

- Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Mattila KT, Tuominen EK, Kauko T, Äärimaa V. Treatment of Nontraumatic Rotator Cuff Tears: A Randomized Controlled Trial with Two Years of Clinical and Imaging Follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015 Nov 4;97(21):1729-37. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01051. Erratum in: J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016 Jan 6;98(1):e1. PMID: 26537160.

- Kukkonen J, Ryösä A, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, Kauko T, Mattila K, Äärimaa V. Operative versus conservative treatment of small, nontraumatic supraspinatus tears in patients older than 55 years: over 5-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021 Nov;30(11):2455-2464. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.03.133. Epub 2021 Mar 24. PMID: 33774172.

- Kuhn JE, Dunn WR, Sanders R, An Q, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, Brophy RH, Carey JL, Holloway BG, Jones GL, Ma CB, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Poddar SK, Smith MV, Spencer EE, Vidal AF, Wolf BR, Wright RW; MOON Shoulder Group. Effectiveness of physical therapy in treating atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013 Oct;22(10):1371-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.026. Epub 2013 Mar 27. PMID: 23540577; PMCID: PMC3748251.

- Lambers Heerspink FO, van Raay JJ, Koorevaar RC, van Eerden PJ, Westerbeek RE, van 't Riet E, van den Akker-Scheek I, Diercks RL. Comparing surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015 Aug;24(8):1274-81. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.05.040. PMID: 26189808.

- Lambers Heerspink FO, Dorrestijn O, van Raay JJ, Diercks RL. Specific patient-related prognostic factors for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014 Jul;23(7):1073-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.01.001. Epub 2014 Apr 13. PMID: 24725900.

- Lu Y, Sun B, Yang G, Li S, Jiang C. Arthroscopic Repair Benefits Reparable Rotator Cuff Tear Patients Aged 65 Years or Older With a History of Traumatic Events. Arthroscopy. 2023 May;39(5):1150-1158. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2022.12.022. Epub 2022 Dec 28. PMID: 36584804.

- Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom U, Svege I, Hennig T, Tariq R, Smith HJ. Comparison between surgery and physiotherapy in the treatment of small and medium-sized tears of the rotator cuff: A randomised controlled study of 103 patients with one-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010 Jan;92(1):83-91. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B1.22609. PMID: 20044684.

- Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom US, Haldorsen B, Svege IC, Hennig T, Pripp AH, Smith HJ. Tendon repair compared with physiotherapy in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled study in 103 cases with a five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Sep 17;96(18):1504-14. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01393. PMID: 25232074.

- Moosmayer S, Lund G, Seljom US, Haldorsen B, Svege IC, Hennig T, Pripp AH, Smith HJ. At a 10-Year Follow-up, Tendon Repair Is Superior to Physiotherapy in the Treatment of Small and Medium-Sized Rotator Cuff Tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Jun 19;101(12):1050-1060. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.01373. PMID: 31220021.

- Nyring MRK, Olsen BS, Amundsen A, Rasmussen JV. Minimal Clinically Important Differences (MCID) for the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder Index (WOOS) and the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS). Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2021 Sep 22;12:299-306. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S316920. PMID: 34588833; PMCID: PMC8473013

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Cederqvist, 2021

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00695981 and NCT00637013. |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Finland

Funding and conflicts of interest: “Funding This work was supported by grants from the Academy of Finland (grant 12321/13.9.2007) 265646/17.4.2013) and National Competitive Research Funding of the University of Eastern Finland. None of the writers have any conflicts of interest relevant to this article. Competing interests None declared.” |

In this literature summary, the patients with full-thickness ruptures were included Surgical group: 50/95 were full-thickness ruptures, of which 44 (88%%) in the supraspinatus Non-surgical group: 48/95 were full-thickness ruptures, of which 44 (92%) in the supraspinatus

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 48

Important prognostic factors2: in general intervention groups; not reported for full-thickness only age ± SD I: 56 y (SD 8) C: 56 y (SD 8) Sex: I: 50/95 (53%) M C: 52/95 (55%) M

Groups comparable at baseline. |

Repair: Arthroscopic or mini-open single-row surgical treatment of cuff repair In surgery, patients without full-thickness tendon tears underwent arthroscopic SAD. Patients with full-thickness tears received rotator cuff repair with single-row technique, with one or more bone anchors, via either an arthroscopic or mini-open approach. When necessary, patients underwent acromioplasty, acromioclavicular joint resection or tenotomy of the long head of the biceps.

All patients followed a structured postoperative rehabilitation protocol (see online supplemental appendix). |

Physiotherapy: cold pack + exercises + stretching, manual therapy, cross-friction massages Patients randomised to non-surgical treatment continued the previously initiated rehabilitation programme. Unsuccessful non-surgical treatment was defined as severe pain or poor subjective function in the shoulder during follow-up. These patients were offered a surgical intervention.

All patients followed a structured postoperative rehabilitation protocol (see online supplemental appendix).

|

Length of follow-up: 2 years

Loss-to-follow-up & incomplete outcome data: Constant score 12 months I: 18 (19%) C: 18 (19%) 24 months: I: 15 (16%) C: 14 (15%) VAS pain score 12 months I: 18 (19%) C: 19 (20%) 24 months: I: 15 (16%) C: 15 (16%)

|

Complications “No patients required re-operation, and no serious adverse events were noted.”

PROMS: function, strength, pain combined Constant score FU 2 years, change from baseline I: +20.0 (16.4 to 23.7) C: +13.0 (9.4 to 16.7) MD 7.0 (95%CI 1.8 to 12.2; p=0.008).

Calculated in RevMan I: +20.0 (SD 16.1769), n=80 C: +13.0 (SD 16.1769), n=80 MD 7.00 (95% CI 1.99 to 12.01)

Pain VAS 0-100 change score from baseline, mean (95% CI) FU 2 years I: -37 (95% CI 31 to 43) C: -24 (95% CI 18 to 30) MD -13 (95% CI 5 to 22; p=0.002).

Calculated in RevMan: I: -37.0 (SD 26.9616), n=80 C: -24.0 (SD 26.9616), n=80 MD 13.00 (95% CI -4.64 to 21.36) Not included in plot, as change scores and difference scale (0-100) were used

Patient satisfaction Not reported |

|

|

Kukkonen, 2014 / Kukkonen, 2015 a en b / Kukkonen 2019

NCT01116518 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: three hospitals in Finland (Turku University Hospital, Kuopio University Hospital and Hatanpää Hospital) between October 2007 and December 2012; Finland

Funding and conflicts of interest: Not mentioned explicitly; “No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.”

|

Group 1 (surgery + physiotherapy) and group 3 (physiotherapy) were included in the current literature summary.

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 60 Control: 60

Important prognostic factors2: Female (n, %) I: 26/55 (47%) C: 31/55 (56%)

Mean (SD) age (yrs) I: 65y (SD 6.0) C: 65y (SD 5.8)

Groups comparable at baseline.

|

Repair: surgical rotator cuff repair + acromioplasty + immobilization in a sling for 3 weeks + physiotherapy

(group 3 in article) |

Physiotherapy:

instructions + home exercises + 10 sessions of physiotherapy

(group 1 in article) |

Length of follow-up: 60 months / 5 years (mean follow-up period of 6.2 years)

Loss-to-follow-up & incomplete outcome data: Intervention (group 3) Baseline data: n=59 shoulders Intervention: n=55 12m FU: 55 24m FU: 54 60m FU: 49

Control (group 1) Baseline data: n=58 shoulders Intervention: n=60 12m FU: 55 24m FU: 55 60m FU: 51

|

Complications “No treatment-related complications occurred in any group.”

PROMS: function, strength, pain combined Constant score (range from 0 to 100 points: worst and best shoulder function) FU 1 year I: 78.1 (SD 12.1), n=55 C: 74.2 (SD 14.3), n=55 FU 2 years I: 80.2 (SD 13.0), n=54 C: 76 (SD 11.9), n=55 Calculated in RevMan: MD 4.20 (95% CI -0.48 to 8.88) Mean change score baseline to 24 M (95% CI) I: 22.6 points (18.4 to 26.8 points) C: 18.4 points (14.2 to 22.6 points) FU 5 years Mean (SD) score (95% CI) I: 78.7 (74.4- 83.0) C: 75.6 (71.5- 79.8) Calculated in RevMan: I: 78.7 (SD 14.9704), n=49 C: 75.6 (SD 14.5775), n=51 MD 3.10 (95% CI -2.69 to 8.89) Mean change (95% CI) I: 20.0 (15.0-24.9) C: 18.5 (13.6-23.4)

Pain VAS pain scale 0-10; mean (SD) FU 1 year I: 0.9 (SD 2.1), N=55 C: 1.2 (SD 1.9), N=55 Calculated in RevMan: MD -0.30 (95% CI -1.05 to 0.45) FU 2 years I: 0.6 (SD 1.6), N=54 C: 1.4 (SD 2.1), N=55 Calculated in RevMan: MD -0.80 (95% CI -1.50 to -0.10) VAS change score for pain I: -2.0 C: -1.3 FU 5 years VAS pain scale; mean (95% CI) I: 0.62 (0.16-1.08) C: 1.43 (0.98-1.88) Calculated in RevMan I: 0.62 (SD 1.6015), n=49 C: 1.43 (SD 1.6), n=51 MD -0.81 (95% CI -1.44 to -0.18) Mean change in VAS pain score (95% CI)* I: -1.85 (-2.66 to -1.04) C: -1.55 (-2.35 to -0.75)

Patient satisfaction At the control visits patients were asked if they were satisfied or dissatisfied with the treatment outcome FU 1 year I: 95% C: 87% FU 2 years I: 94% C: 89% FU 5 years I: 91.8% C: 88.2% |

|

|

Lambers Heerspink, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: January 2009 and December 2012

Funding and conflicts of interest: “This study received a grant from Anna Fonds. There was no involvement in data collection, data analysis, the preparation, or editing of the manuscript by Anna Fonds. The authors, their immediate families, and any research foundations with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.” |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 25 Control: 31

Important prognostic factors2: Age, SD: I: 60.8, 7.2 C: 60.5, 7.0 Sex: I: 60% M C: 64.5% M

Groups comparable at baseline.

|

Repair: Surgical treatment

Surgery was scheduled within 6 weeks of inclusion and was done with the patient under general anaesthesia, supplemented with an interscalene brachial plexus block. The operation was performed in beach chair position using an anterolateral miniopen approach. The coraco-acromial ligament was detached from its insertion, and the subacromial bursa was excised. The anteroinferior part of the acromion was removed. The footprint of the rotator cuff on the greater tuberosity was debrided, and a bleeding bony bed was created. Side-to-side repair and repair augmented with bone anchors were performed depending on the shape of the rupture. A side-to-side repair was performed in 6 patients. The deltoid muscle was reattached to the acromion by transosseous refixation.

The repair in 14 patients was augmented using bone anchors. The tear in 2 patients could not be repaired, and no rotator cuff rupture was found in 2 patients despite an MRI-supported diagnosis. These 4 patients were excluded for primary per-protocol analysis but were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. After surgery, the patient wore a sling for 6 weeks. Patients were referred for physical therapy and treatment was commenced according to a standardized protocol.21 In the first 6 weeks, only passive movements were allowed. Passive GH movement was performed to prevent loss of mobility. The mobility of elbow and wrist was passively maintained. Circumduction exercises were allowed. After 6 weeks, active guided treatment was started and was expanded to active treatment. Strength development was started 3 months postoperatively. |

Conservative treatment: Subacromial steroid infiltration, physiotherapy, and analgesic medication; further options: analgesic medication with NSAIDs, paracetamol, or tramadol)

Treatment in the conservative group consisted of subacromial steroid infiltration, physiotherapy, and analgesic medication. After inclusion, patients were given an infiltration in the subacromial space by a posterior approach. If the first infiltration gave no pain relief, a second infiltration was performed under radiologic or ultrasound guidance. The number of subacromial infiltrations was limited to a maximum of 3. Further conservative treatment options consisted of analgesic medication with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), paracetamol, or tramadol. Patients were referred to a physio-therapist. The Department of Physical Therapy of Martini Hospital, Groningen, The Netherlands, developed a standardized physical therapy protocol for the conservative treatment of rotator cuff tears.21 In addition to explaining the cause of the symptoms and the rehabilitation protocol, the physiotherapist advised about activities of daily living (ADL). Passive GH and scapulothoracic movements were performed, and static and dynamic exercises were started. The aim of these exercises was to improve GH and scapulothoracic musculature. Poor posture was corrected. In weeks 4 to 6, exercises were gradually increased, and deltoid training was started. In weeks 6 to 12, rehabilitation was aimed at further optimization of mobility and strength regeneration of the remaining cuff and deltoid. Physical therapy was continued until patients reached an optimum range of motion and an improvement in strength was achieved. Three patients were dissatisfied with the result of conservative treatment and a decision was made to perform rotator cuff repair (discontinued intervention). In 2 of these patients, data were available until 3 months after treatment and in the other patient until 6 months after treatment. |

Length of follow-up: 12m

Loss-to-follow-up & incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 20/25 analysed (1 moved, 4 excluded due to failed surgery) Control: 25/31 analysed (3 discontinued intervention, 1 death, 1 moved)

|

Complications Not reported

PROMS: function, strength, pain combined CMS, mean (SD) FU 1 year I: 81.9 (15.6); n=20 C: 73.7 (18.4), n=25 Calculated in RevMan: MD: 8.20 (95% CI -1.74 to 18.14) DSST FU 1 year I: 11.0 (2.8); n=20 C: 9.7 (3.6), n=25 Calculated in RevMan: MD 1.30 (95% CI -1.35 to 3.95)

Pain VAS pain score, 0-10; 0 represents no pain and restriction, and 10 the most likely pain and disability FU 1 year I: 2.2 (1.9), n=20 C: 3.2 (2.1), n=25 Calculated in RevMan: MD -1.00 (95% CI -2.17 to 0.17)

Patient satisfaction Not reported; “Three patients were dissatisfied with the result of conservative treatment and a decision was made to perform rotator cuff repair (discontinued intervention). In 2 of these patients, data were available until 3 months after treatment and in the other patient until 6 months after treatment.”

|

|

|

Moosmayer, 2010 / Moosmayer, 2014 / Moosmayer, 2019 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: Single-centre; Norway

Funding and conflicts of interest: “One or more of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of an aspect of this work. None of the authors, or their institution(s), have had any financial relation-ship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with any entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. Also, no author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article”

Source of Funding “In support of the research for this manuscript, outside funding was given by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. Funds were used to pay for salaries. The source of funding did not play a role in the investigation.” |

Inclusion criteria:

Traumatic and atraumatic tears were included.

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 52 Control: 51

Important prognostic factors2: age (range): I: 59 (44 to 75) C: 61 (46 to 75) Sex: I: 37/52, 71% M C:36/51, 71 % M

Groups comparable at baseline

|

Repair: Surgical treatment of cuff repair (through a deltoid splitting approach, anteroinferior acromioplasty was performed) |

Physiotherapy: physiotherapy and exercises |

Length of follow-up: 10 years

Loss-to-follow-up & incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 12m FU: 51 24m FU: 51 5y FU: 51 10y: 48

Control: 12m FU: 51 24m FU: 50 5y FU: 55 10y: 43

|

Complications Relevant complications according to guideline development group

Index shoulder, need for additional physiotherapy I: 1 (within 2 years) C: 3 (after 5 years)

Index shoulder, need for: I: reoperation with acromioplasty and biceps tenotomy (n = 1) C: Physiotherapy (n = 1)

C: Glenohumeral arthrosis, conservatively treated (n = 1)

PROMS: function, strength, pain combined Constant score, mean ± SD FU 1 year I: 77.7 ± 13.4, n=52 C: 70.3 ± 19.1, n=51 Calculated in RevMan: MD 7.40 [1.00, 13.80] FU 2 years I: 79.3 ± 13.6 C: 77.7 ± 14.9 Calculated in RevMan: MD 1.60 [-3.97, 7.17] FU 5 years I: 79.8 ± 15.0 C: 74.2 ± 20.3 Calculated in RevMan: MD 5.60 [-1.16, 12.36] FU 10 years I: 80.5 ± 9.8 C: 71.8 ± 17.8 Calculated in RevMan: MD 8.70 [2.70, 14.70]

ASES score - self-report section of the ASES score; 0-100; higher score indicating better functioning; mean ± SD FU 1 year I: 93.6 ± 12.5 C: 83.6 ± 18.3 Calculated in RevMan: MD 10.00 [3.92, 16.08] FU 2 years I: 93.1 ± 13.9 C: 88.0 ± 14.9 Calculated in RevMan: MD 5.10 [-0.52, 10.72] FU 5 years I: 92.8 ± 13.3 C: 85.4 ± 21.0 Calculated in RevMan: MD 7.40 [0.76, 14.04] FU 10 years I: 94.0 ± 9.5 C: 80.0 ± 20.2 Calculated in RevMan: MD 14.00 [7.39, 20.61]

Pain VAS pain (cm); mean ± SD FU 1 year I: 0.5 ± 1.2 C: 1.6 ± 1.6 Calculated in RevMan: MD -1.10 [-1.65, -0.55] FU 2 years I: 0.7 ± 1.5 C: 1.4 ± 1.4 Calculated in RevMan: MD -0.70 [-1.27, -0.13] FU 5 years I: 0.6 ± 1.4 C: 1.6 ± 1.6 Calculated in RevMan: MD -1.00 [-1.57, -0.43] FU 10 years I: 0.6 ± 1.3 C: 2.3 ± 2.4 Calculated in RevMan: MD -1.70 [-2.51, -0.89]

Patient satisfaction VAS – scale: After 1, 5, and 10 years, patients had to answer the question “How satisfied are you with the treatment result of your shoulder?” on a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (very unsatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). FU 1 year I: 9.0 (1.0 to 10.0) C: 7.2 (0.0 to 10.0) FU 2 years I: C: FU 5 years I: 9.2 cm C: 8.3 cm MD 1.0 cm [95% CI, 0.1 to 1.8 cm]; p = 0.03) FU 10 years I: 9.2 cm C: 8.2 cm MD 0.97 cm [95% CI, 0.13 to 1.82 cm]; p = 0.03) |

|

Risk of bias table

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Cederqvist, 2021 |

Probably yes

Reason: “A research assistant not involved in the study prepared a computer-generated, block randomisation list and sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes for patient randomisation.” |

Probably yes

Reason: Reason: no information about allocation concealment

|

Definitely no

Reason: surgery vs. no surgery cannot be blinded; “The information regarding the treatment group was open to patients, the treating physicians and the study physiotherapists.” |

Definitely no

Reason: missing outcome data comparable between groups but ranged from 16-20 % in 1-year and 2-year follow-up data. |

Probably no

Reason: Brindisino (2021): “RoB in measuring the outcomes showed high risk” and “selection of reported outcomes showed some concern” |

…

Reason: Trial registered |

High risk of bias

|

|

Kukkonen, 2014 / Kukkonen, 2015 a en b / Kukkonen 2019

NCT01116518 |

Probably yes

Reason: method for randomization not described

|

Probably yes

Reason: no information about allocation concealment “… using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. The randomization was stratified according to participating hospital into 3 blocks.” |

Probably no

Reason: surgery vs. no surgery cannot be blinded; “After randomization, the patient and the treating physician were openly informed of the treatment group. The radiologists were blinded to clinical patient data.”

|

Probably yes

Reason: “One strength of our study is a good follow-up rate of 83%. The cases of dropout partly comprised deceased patients, and some patients were not available because of migration to another district” |

Definitely yes

Reason: outcomes defined and reported steadily over the years of FU. |

Probably yes

Reason: Trial registered, outcomes and population the same over the FU years |

Some concerns (all outcomes) |

|

Lambers Heerspink, 2015

Netherlands Trial Registry (NTR TC 2343) |

Probably yes

Reason: “Randomization was done by hand using 100 prefilled opaque sealed envelopes (50 for each treatment arm).” |

Probably yes

Reason: no information about allocation concealment

|

Probably no

Reason: surgery vs. no surgery cannot be blinded; “Because we were dealing with a surgical vs conservative therapy setup, patients and outcome assessors could not be blinded for the type of treatment” |

Probably yes

Reason: 25/31 and 20/25 included in follow-up |

Probably yes

Reason: outcomes defined and reported steadily over the years of FU. Brindisino (2021): “RoB in measuring the outcomes showed high risk” and “selection of reported outcomes showed some concern” |

Probably yes

Reason: Trial registered, outcomes and population the same over the FU years “As described in the discussion, the inclusion of patients for this trial was difficult. We eventually had to terminate the inclusion prematurely, resulting in an unequal number of participants in the conservative and surgical groups.” |

Some concerns (all outcomes) |

|

Moosmayer, 2010 / Moosmayer, 2014 / Moosmayer, 2019

NCT00852657 |

Probably yes

Reason: “A computer-generated randomisation list (block length 20, ratio 1:1) was drawn up by our statistician. Sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes were used to assign treatment according to the participants’ study number, given at baseline assessment. The randomisation sequence was concealed from the study’s collaborators until treatment was assigned. Only the outcome assessor (TH) remained blinded throughout the study.” |

Definitely yes

Reason: “Sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes were used to assign treatment according to the participants’ study number, given at baseline assessment. The randomisation sequence was concealed from the study’s collaborators until treatment was assigned.” |

Probably no

Reason: surgery vs. no surgery cannot be blinded “Only the outcome assessor (TH) remained blinded throughout the study.” |

Probably yes

Reason: 48/52 and 43/51 included in 10-year follow-up |

Definitely yes

Reason: outcomes defined and reported steadily over the years of FU. |

Probably yes

Reason: Trial registered, outcomes and population the same over the FU years |

Some concerns (all outcomes) |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abdul-Wahab TA, Betancourt JP, Hassan F, Thani SA, Choueiri H, Jain NB, Malanga GA, Murrell WD, Prasad A, Verborgt O. Initial treatment of complete rotator cuff tear and transition to surgical treatment: systematic review of the evidence. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2016 May 19;6(1):35-47. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2016.6.1.035. PMID: 27331030; PMCID: PMC4915460. |

Wrong outcome and more recent review available |

|

Arce G, Bak K, Bain G, Calvo E, Ejnisman B, Di Giacomo G, Gutierrez V, Guttmann D, Itoi E, Ben Kibler W, Ludvigsen T, Mazzocca A, de Castro Pochini A, Savoie F 3rd, Sugaya H, Uribe J, Vergara F, Willems J, Yoo YS, McNeil JW 2nd, Provencher MT. Management of disorders of the rotator cuff: proceedings of the ISAKOS upper extremity committee consensus meeting. Arthroscopy. 2013 Nov;29(11):1840-50. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.07.265. Epub 2013 Sep 13. PMID: 24041864. |

Wrong study design |

|

Brindisino F, Salomon M, Giagio S, Pastore C, Innocenti T. Rotator cuff repair vs. nonoperative treatment: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021 Nov;30(11):2648-2659. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.04.040. Epub 2021 May 19. PMID: 34020002. |

Relevant studies included individually |

|

Candela V, Longo UG, Di Naro C, Facchinetti G, Marchetti A, Sciotti G, Santamaria G, Piergentili I, De Marinis MG, Nazarian A, Denaro V. A Historical Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials in Rotator Cuff Tears. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 20;17(18):6863. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186863. PMID: 32962199; PMCID: PMC7558823. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Cederqvist S, Flinkkilä T, Ylinen J, Kautiainen H, Tuominen A, Kiviranta I, Paloneva J; Surgery for rotator cuff disease Finland (SURFIN) Investigators. Response to: 'Correspondence on 'Non-surgical and surgical treatments for rotator cuff disease: a pragmatic randomised clinical trial with 2-year follow-up after initial rehabilitation'' by Randelli et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Feb 3:annrheumdis-2020-219782. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219782. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33536163. |

wrong publication type |

|

Erratum regarding previously published articles (Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma (2020) 11(S1) (S86–S92), (S0976566219303029), (10.1016/j.jcot.2019.09.014)) |

wrong population |

|

Erratum regarding previously published articles (Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma (2021) 20, (S0976566221003404), (10.1016/j.jcot.2021.06.003)) |

wrong publication type |

|

Fahy K, Galvin R, Lewis J, Mc Creesh K. Exercise as effective as surgery in improving quality of life, disability, and pain for large to massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2022 Oct;61:102597. doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2022.102597. Epub 2022 Jun 10. PMID: 35724568. |

wrong population |

|

Franco ESB, Puga MEDS, Imoto AM, Almeida J, Mata VD, Peccin S. What do Cochrane Systematic Reviews say about conservative and surgical therapeutic interventions for treating rotator cuff disease? Synthesis of evidence. Sao Paulo Med J. 2019 Nov-Dec;137(6):543-549. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2019.0275160919. PMID: 32159641; PMCID: PMC9754280. |

wrong publication type |

|

Garibaldi R, Altomare D, Sconza C, Kon E, Castagna A, Marcacci M, Monina E, Di Matteo B. Conservative management vs. surgical repair in degenerative rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021 Jan;25(2):609-619. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202101_24619. PMID: 33577014. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Hopewell S, Keene DJ, Marian IR, Dritsaki M, Heine P, Cureton L, Dutton SJ, Dakin H, Carr A, Hamilton W, Hansen Z, Jaggi A, Littlewood C, Barker KL, Gray A, Lamb SE; GRASP Trial Group. Progressive exercise compared with best practice advice, with or without corticosteroid injection, for the treatment of patients with rotator cuff disorders (GRASP): a multicentre, pragmatic, 2 × 2 factorial, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Jul 31;398(10298):416-428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00846-1. Epub 2021 Jul 12. PMID: 34265255; PMCID: PMC8343092. |

wrong comparison |

|

Huang DG, Wu YL, Chen PF, Xia CL, Lin ZJ, Song JQ. Surgical or nonsurgical treatment for nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: Study protocol clinical trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 May;99(18):e20027. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020027. PMID: 32358381; PMCID: PMC7440173. |

wrong publication type |

|

Jain NB, Ayers GD, Fan R, Kuhn JE, Warner JJP, Baumgarten KM, Matzkin E, Higgins LD. Comparative Effectiveness of Operative Versus Nonoperative Treatment for Rotator Cuff Tears: A Propensity Score Analysis From the ROW Cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Nov;47(13):3065-3072. doi: 10.1177/0363546519873840. Epub 2019 Sep 13. PMID: 31518155; PMCID: PMC7325686. |

wrong study design |

|

Jain NB, Ayers GD, Koudelková H, Archer KR, Dickinson R, Richardson B, Derryberry M, Kuhn JE; ARC Trial Group. Operative vs Nonoperative Treatment for Atraumatic Rotator Cuff Tears: A Trial Protocol for the Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Pragmatic Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019 Aug 2;2(8):e199050. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.9050. PMID: 31397866; PMCID: PMC6692688. |

wrong publication type |

|

Kahlenberg CA, Dare DM, Dines JS. Further Research Is Needed to Define the Benefits of Non-operative Rotator Cuff Treatment. HSS J. 2016 Oct;12(3):291-294. doi: 10.1007/s11420-016-9495-7. Epub 2016 Feb 29. PMID: 27703426; PMCID: PMC5026654. |

wrong publication type |

|

Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Heikkinen J, Johnston RV, Page CM, Buchbinder R. Surgery for rotator cuff tears. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Dec 9;12(12):CD013502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013502. PMID: 31813166; PMCID: PMC6900168. |

wrong population |

|

Kim S, Hwang J, Kim MJ, Lim JY, Lee WH, Choi JE. Systematic review with network meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of rotator cuff tear treatment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018;34(1):78-86. doi: 10.1017/S0266462317004500. Epub 2018 Feb 22. PMID: 29467045. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Lavoie-Gagne O, Farah G, Lu Y, Mehta N, Parvaresh KC, Forsythe B. Physical Therapy Combined With Subacromial Cortisone Injection Is a First-Line Treatment Whereas Acromioplasty With Physical Therapy Is Best if Nonoperative Interventions Fail for the Management of Subacromial Impingement: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Arthroscopy. 2022 Aug;38(8):2511-2524. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2022.02.008. Epub 2022 Feb 19. PMID: 35189304. |

wrong population |

|

Littlewood C, Wade J, Butler-Walley S, Lewis M, Beard D, Rangan A, Bhabra G, Kalogrianitis S, Kelly C, Mehta S, Singh HP, Smith M, Tambe A, Tyler J, Foster NE. Protocol for a multi-site pilot and feasibility randomised controlled trial: Surgery versus PhysiothErapist-leD exercise for traumatic tears of the rotator cuff (the SPeEDy study). Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2021 Jan 7;7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00714-x. PMID: 33413664; PMCID: PMC7788278. |

wrong publication type |

|

Longo UG, Risi Ambrogioni L, Candela V, Berton A, Carnevale A, Schena E, Denaro V. Conservative versus surgical management for patients with rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and META-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021 Jan 8;22(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03872-4. Erratum in: BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021 Sep 2;22(1):752. PMID: 33419401; PMCID: PMC7796609. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Longo UG, Risi Ambrogioni L, Candela V, Berton A, Carnevale A, Schena E, Denaro V. Conservative versus surgical management for patients with rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and META-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021 Jan 8;22(1):50. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03872-4. Erratum in: BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021 Sep 2;22(1):752. PMID: 33419401; PMCID: PMC7796609. |

correction for review that was not included in this summary |

|

Naimark M, Trinh T, Robbins C, Rodoni B, Carpenter J, Bedi A, Miller B. Effect of Muscle Quality on Operative and Nonoperative Treatment of Rotator Cuff Tears. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019 Aug 5;7(8):2325967119863010. doi: 10.1177/2325967119863010. PMID: 31428659; PMCID: PMC6683312. |

wrong outcome |

|

Narvani AA, Imam MA, Godenèche A, Calvo E, Corbett S, Wallace AL, Itoi E. Degenerative rotator cuff tear, repair or not repair? A review of current evidence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2020 Apr;102(4):248-255. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2019.0173. Epub 2020 Jan 3. PMID: 31896272; PMCID: PMC7099167. |

wrong publication type |

|

Nazari G, MacDermid JC, Bryant D, Athwal GS. The effectiveness of surgical vs conservative interventions on pain and function in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019 May 29;14(5):e0216961. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216961. PMID: 31141546; PMCID: PMC6541263. |

wrong population |

|

Piper CC, Hughes AJ, Ma Y, Wang H, Neviaser AS. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Mar;27(3):572-576. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.09.032. Epub 2017 Nov 21. PMID: 29169957. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Randelli P, Coletto LA, Menon A, Caporali R. Correspondence on 'Non-surgical and surgical treatments for rotator cuff disease: a pragmatic randomised clinical trial with 2-year follow-up after initial rehabilitation'. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Feb 3:annrheumdis-2020-219751. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219751. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33536162. |

wrong publication type |

|

Ranebo MC, Björnsson Hallgren HC, Holmgren T, Adolfsson LE. Surgery and physiotherapy were both successful in the treatment of small, acute, traumatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective randomized trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020 Mar;29(3):459-470. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.10.013. Epub 2020 Jan 7. PMID: 31924516.

|

|

|

Ryösä A, Kukkonen J, Björnsson Hallgren HC, Moosmayer S, Holmgren T, Ranebo M, Bøe B, Äärimaa V; ACCURATE study group. Acute Cuff Tear Repair Trial (ACCURATE): protocol for a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial on the efficacy of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. BMJ Open. 2019 May 19;9(5):e025022. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025022. PMID: 31110087; PMCID: PMC6530362. |

wrong publication type |

|

Ryösä A, Laimi K, Äärimaa V, Lehtimäki K, Kukkonen J, Saltychev M. Surgery or conservative treatment for rotator cuff tear: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017 Jul;39(14):1357-1363. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2016.1198431. Epub 2016 Jul 6. PMID: 27385156. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Schemitsch C, Chahal J, Vicente M, Nowak L, Flurin PH, Lambers Heerspink F, Henry P, Nauth A. Surgical repair versus conservative treatment and subacromial decompression for the treatment of rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Bone Joint J. 2019 Sep;101-B(9):1100-1106. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B9.BJJ-2018-1591.R1. PMID: 31474132. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Schmucker C, Titscher V, Braun C, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Gartlehner G, Meerpohl J. Surgical and Non-Surgical Interventions in Complete Rotator Cuff Tears. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 Sep 18;117(38):633-640. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0633. PMID: 33263527; PMCID: PMC7817785. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Tashjian RZ. Is there evidence in favor of surgical interventions for the subacromial impingement syndrome? Clin J Sport Med. 2013 Sep;23(5):406-7. doi: 10.1097/01.jsm.0000433152.74183.53. PMID: 23989383. |

wrong population |

|

Zadro JR, O'Keeffe M, Ferreira GE, Traeger AC, Gamble AR, Page R, Herbert RD, Harris IA, Maher CG. Diagnostic labels and advice for rotator cuff disease influence perceived need for shoulder surgery: an online randomised experiment. J Physiother. 2022 Oct;68(4):269-276. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2022.09.005. Epub 2022 Oct 17. PMID: 36257876. |

wrong population, intervention, outcome |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 03-02-2025

Laatst geautoriseerd : 03-02-2025

Geplande herbeoordeling : 03-02-2028

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het herzien van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met Subacromiaal Pijnsyndroom van de Schouder (SAPS).

Werkgroep

dr. J.J.A.M (Jos) van Raaij, orthopedisch chirurg Martiniziekenhuis Groningen, NOV (voorzitter)

dr. C.P.J. (Cornelis) Visser, orthopedisch chirurg Alrijne en Eisenhower Kliniek, NOV

dr. F.O. (Okke) Lambers Heerspink, orthopedisch chirurg VieCuri Medisch Centrum, NOV

dr. E.J.D. (Bart Jan) Veen, orthopedisch chirurg Medisch Spectrum Twente, NOV

dr. O. (Oscar) Dorrestijn, orthopedisch Chirurg Sint Maartenskliniek, NOV

dr. M.J.C. Maarten Leijs, orthopedisch chirurg Reinier Haga Orthopedisch Centrum , NOV

dr. D. (Dennis) van Poppel, manueel therapeut, sportfysiotherapeut PECE Zorg, Fontys Paramedisch, KNGF

drs. P.A. (Peter) Stroomberg, radioloog, Isala, NVvR

dr. R.P.G. (Ramon) Ottenheijm, huisarts, vakgroep huisartsgeneeskunde, Universiteit Maastricht, NHG

dr. J.W. (Jan Willem) Kallewaard, anesthesioloog Rijnstate, NVA

drs. T.J.W. (Tjerk) de Ruiter, revalidatiearts De Ruiter Revalidatie, VRA

dr. H.A. (Henk) Martens, reumatoloog Sint Maartenskliniek, NVR

Klankbordgroep

drs. R.J. (René) Naber, Bedrijfsarts arbodienst Amsterdam UMC, NVAB