Diagnostische testen voor SAPS

Uitgangsvraag

Welke fysisch diagnostische tests zijn het meest geschikt voor het diagnosticeren van SAPS?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik na anamnese het lichamelijk onderzoek om de diagnose SAPS of rotator cuff ruptuur te stellen, om te bepalen of en welk vervolgonderzoek nodig is en/of om te bepalen of fysieke klachten te beïnvloeden zijn.

Gebruik bij patiënten met schouderpijn een enkele test voor het aantonen dan wel uitsluiten van SAPS of een rotator cuff ruptuur.

- Een enkele test is voldoende bij verdenking op SAPS. Bijvoorbeeld de empty can test (insluiten indien positief).

- Gebruik bij verdenking op een (posterieure) rotator cuff ruptuur bij voorkeur de lateral rotation lag sign (insluiten indien positief).

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de diagnostische accuratesse van het gebruik van een enkele fysiek diagnostische test vergeleken met een combinatie van meerdere fysiek diagnostische testen voor het diagnosticeren van SAPS (met uitzondering van pathologie aan de subscapularispees). Er zijn twee studies geïncludeerd die enkele testen vergeleken hebben met een combinatie van testen; echter wel in twee verschillende subcategorieën van SAPS.

Beide studies rapporteerden de sensitiviteit en specificiteit (cruciale uitkomstmaten). De bewijskracht voor beide uitkomstmaten was echter laag, waardoor er weinig vertrouwen is in deze gerapporteerde maten. De reden hiervoor zijn de brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen rondom de gerapporteerde puntschatters. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten is laag. De vooraf gedefinieerde belangrijke uitkomstmaten pijn, functionaliteit en terugkeer naar werk en vrije tijdsbesteding werden niet gerapporteerd in beide studies en kunnen daarom ook geen verdere richting geven. Hier bestaat een kennisvraag. Derhalve is het hele diagnostische proces van belang, waarbij naast het lichamelijk onderzoek ook anamnese en aanvullend onderzoek worden verricht. Fysische testen gericht op andere pathologie in en om het schouder gewricht zijn nodig om verder richting te geven.

Diagnostisch traject van de patiënt

Patiënten met non-traumatische schouderpijn die zich presenteren bij een zorgverlener zullen na een uitvoerige anamnese onderzocht worden. Om al richting te geven aan de mogelijke diagnose is het belang van deze anamnese groot. Voor inspectie en beoordeling van de bewegelijkheid zijn er meerdere fysieke tests beschikbaar om SAPS meer of minder aannemelijk te maken. Hierbij is het belangrijk om eerst andere oorzaken van schouderpijn uit te sluiten, zoals intra-articulaire pathologie, AC artrose, en totaal rupturen, maar ook oncologische en neurologische aandoeningen. Hierbij kan een röntgenfoto of een echo meer duidelijkheid geven. Het onderzoek van de cervicale wervelkolom en psychosociale factoren vallen buiten de afbakening van deze module.

SAPS is een beschrijving van een typisch pijnpatroon van de schouder. De oorzaak is echter niet altijd duidelijk. De besproken testen compromitteren de subacromiale ruimte of er wordt getracht de rotator cuff aan te spannen. Compromittering van de subacromiale ruimte kan zowel intrinsiek als extrinsiek ontstaan. Intrinsieke compromittering kan ontstaan door degeneratieve veranderingen in de cuff al dan niet gepaard gaande met een subacromiale bursitis, en extrinsieke compromittering kan ontstaan door mechanische oorzaken op basis van houdingsproblematiek of anatomische veranderingen (Consigliere, 2018). Door toepassing van de besproken testen wordt hypothetisch gezien de pijn geprovoceerd en kan gedetecteerd worden of de rotator cuff intact is of samen met de bursa geprikkeld is.

Daarnaast kan uitvoeren van anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek meerdere doelstellingen hebben. De keuze van in te zetten methodiek (testen) zal bepaald worden door deze doelstelling. De eerder beschreven literatuur in deze module heeft betrekking op het stellen van de diagnose SAPS. Lichamelijk onderzoek kan bijvoorbeeld echter ook als doel hebben om te bepalen of fysieke klachten positief te beïnvloeden zijn. In dit kader zouden ook symptom modification testen ingezet kunnen worden (Riley 2020, Lewis 2016).

Reflectie op de literatuur

Beide aangehaalde studies (Michener, 2009; Somerville, 2014) zijn meer dan tien jaar oud. Dit geeft impliciet aan dat dit niet een makkelijk onderwerp is. De moeilijkheid ligt in het juist diagnosticeren en vervolgens de verschillende testen uitvoeren.

De studie van Michener (2009) beschrijft SAPS patiënten met een intacte rotator cuff, terwijl Somerville (2014) juist de SAPS patiënt met (partiele) cuff rupturen heeft onderzocht. Daarnaast is er een verschil in gehanteerde fysische testen. In beide studies worden patiënten op basis van een arthroscopie en MRI gediagnosticeerd. Degeneratieve afwijkingen in de schouder hoeven echter niet altijd symptomatisch te zijn (Girish, 2011), zoals de opstroping van de subacromiale bursa (Daghir, 2011) of artrose van het AC gewricht (Veen, 2018).

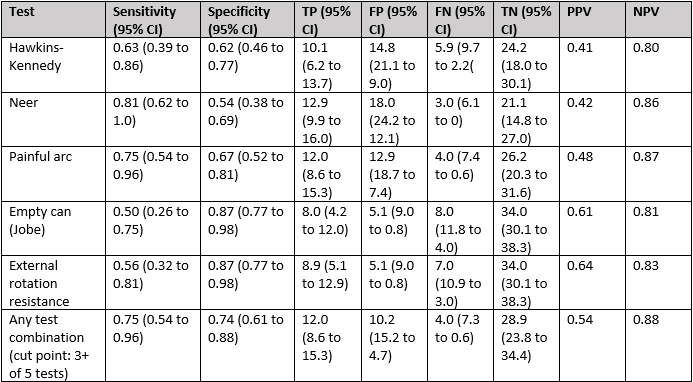

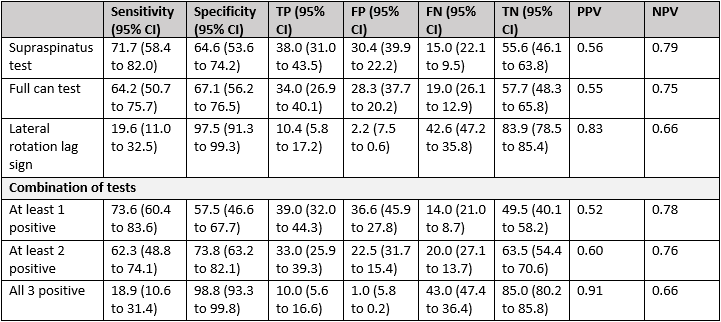

De positief voorspellende waarde (positive predictive value, PPV) is het deel van de onderzochte personen met een positieve testuitslag die de eigenschappen ook daadwerkelijk heeft. Hierop scoren de empty can test (PPV 0,61) en de external rotation resistance test (PPV 0,64) het hoogst in de studie van Michener (2009). Desondanks is het goed om te beseffen dat een patiënt mogelijk fout positief gediagnosticeerd wordt, waarbij het uitvoeren van meerdere testen de kans hierop minimaal verlaagd (PPV 0,54). Terwijl in de studie van Somerville (2014) de PPV (0,91) sterk verhoogd werd bij drie positieve testen.

De negatief voorspellende waarde (negative predictive value, NPV) daarentegen is het deel van de onderzochte personen met een negatieve testuitslag die de eigenschappen inderdaad niet heeft. In de studie van Michener (2009) varieert de NPV tussen de 0,80 en 0,88 voor afzonderlijke of gezamenlijke testen. In de studie Somerville (2014) liggen de waarden tussen 0,66 en 0,79 voor full thickness cuff rupturen en tussen 0,55 en 0,67 voor partial tickness rupturen.

Mocht een patiënt een fout-negatieve diagnose krijgen, dan zou dit ook consequenties hebben. Bijvoorbeeld een goed te behandelen schouderpijn, zoals bij omartrose, krijgt dan de verkeerde therapie en daarmee aanhoudende klachten, hoewel de kans dat het gemist wordt klein is in het hele diagnostische proces in de tweede lijn waarbij ook een röntgenfoto wordt gemaakt.

Daarnaast bestaan er meer fysische testen rondom de rotator cuff die buiten de studie vallen maar van meerwaarde kunnen zijn, zoals de yocum test en countertest with elevation with lateral rotation (Ferenczi, 2018). Tevens is het lastig dat er in de literatuur geen eenduidige terminologie is voor beschreven testen. De suspraspinatus test wordt ook beschreven als empty can test en jobe’s test (Gismervik, 2017).

Toekomstig onderzoek

Ondanks dat SAPS een zeer veel voorkomende aandoening is, blijft de betrouwbaarheid van het lichamelijk onderzoek c.q. diagnostische accuratesse van de beschreven testen beperkt. Een vervolgonderzoek naar de individuele onderzoeken zou wenselijk zijn, waarbij een flowchart opgesteld kan worden waarin de kansen toe- of afnemen per positieve of negatieve test. De controle zou kunnen plaatsvinden op basis van echografie, waarbij een controlegroep lastig is aangezien een pijnsyndroom niet te diagnosticeren is. Veel voorkomende echografische afwijkingen worden ook gevonden bij asymptomatische schouders. Andersom geredeneerd is het belangrijk om andere aandoeningen uit te sluiten. Vooral een cuff ruptuur waarbij de testen ook positief kunnen zijn, maar welke mogelijk in aanmerking komt voor een chirurgische behandeling. Het is de kunst om als zorgprofessional de verschillende uitkomsten op waarde te schatten en af te wegen bij elke individuele patiënt.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De testen die beschreven worden in de studies zijn pijnprovocatie- en functietesten. Hierboven kan het uitvoeren van de testen in meer of mindere mate pijnklachten tijdelijk doen toenemen. De fysieke testen kunnen snel uitgevoerd worden. Het toepassen van nadere diagnostiek kost relatief meer tijd.

Voor de patiënt is het belangrijk om duidelijkheid te krijgen over de diagnose en het te volgen behandelbeleid. Is er inderdaad sprake van SAPS klachten en dient er conservatief beleid te volgen in eerste lijn middels oefen-/fysiotherapie, dienen andere disciplines betrokken te worden (bijv. ergotherapie) of is er een indicatie voor vervolgonderzoek omdat er klinisch vermoeden is dat er een mogelijke indicatie is voor operatieve behandeling van rotator cuff?

Zowel bij een conservatief als operatieve interventie zal met patiënt besproken moeten worden welke verwachtingen er zijn met betrekking tot pijn en functie en hoe het revalidatietraject er grofweg uit zal zien op het gebied van tijd en functionaliteit. Hierdoor kan de patiënt een weloverwogen keuze maken of en wanneer het gekozen beleid ingezet wordt. Dit kan ondersteund worden door pijnmedicatie en/of een subacromiale injectie met steroïden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Het kost niet veel meer tijd om multipele testen uit te voeren en daarmee worden er geen aanvullende kosten verwacht.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De verschillende testen zijn in geoefende handen in een kort tijdsbestek uit te voeren tijdens het lichamelijk onderzoek. Daarmee vormt het geen belemmering. Daarnaast heeft het systematisch beoordelen van een patiënt het voordeel dat er geen elementen worden overgeslagen en gedocumenteerd kunnen worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de diagnostische procedure

De werkgroep heeft onderzocht dat meerdere fysische diagnostische testen afnemen niet bijdraagt aan het stellen van de diagnose SAPS ten opzichte van een enkele test. De werkgroep benadrukt dat de bewijskracht laag is en dat de onderzoeken zijn uitgevoerd met gebruik van een ‘gouden standaard’. Dit was op basis van echografie, MRI of arthroscopische bevindingen. Dit blijft echter een lastig gegeven waarbij dergelijke afwijkingen ook bij asymptomatische schouders worden gevonden. Van alle onderzochte testen om SAPS en/of rotator cuff ruptuur vast te stellen, heeft de lateral rotation lag sign de hoogste positief voorspellende waarde. Het uitvoeren van lichamelijk onderzoek kan helpen rom ichting te geven voor verder aanvullend onderzoek.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Patients presenting with non-traumatic shoulder pain are often seen by care givers in different settings. After anamnesis a thorough physical examination is needed to make a proper differential diagnosis including subacromial pain syndrome. This is done by inspecting the joint and taking note of range of motion. Specific tests are available to provoke pain and influence the subacromial structures. Previous studies suggest the use of a combination of tests (Somerville, 2014; Michener, 2009).

Conclusies

Diagnostic accuracy measures – sensitivity and specificity (crucial)

|

Low GRADE |

There is little confidence in the reported sensitivity and specificity values for a combination of tests compared to solitary tests for the diagnosis of subacromial pain syndrome and for the diagnosis of a supraspinatus tendon tear (full-thickness and full-thickness plus partial-thickness).

Source: Michener, 2009; Somerville, 2014. |

Pain, functionality, and return to work or leisure (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of a combination of tests on pain, functionality, and return to work or leisure when compared with a solitary test for the diagnosis of subacromial pain syndrome and for the diagnosis of a supraspinatus tendon tear (full-thickness and full-thickness plus partial-thickness).

|

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Michener (2009) conducted a prospective study to investigate the reliability and diagnostic accuracy of individual tests and a combination of multiple tests for subacromial impingement syndrome (SAIS). A total of 55 patients were included who presented with shoulder pain (for at least one week) to an orthopedic surgeon’s office. A total of 47 were men and 8 were women, and the mean age was 40.6 years (SD 15.1). The prevalence of shoulder impingement syndrome (SAIS) was 29%; 16 out of 55 patients were confirmed with surgical findings (gold standard) to have SAIS in isolation or in combination with another glenohumeral joint diagnosis. The intraoperative reference standard criteria for SAIS were the presence of any of the following: visually enlarged bursa, fibrotic appearing bursa, or degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon at the superficial aspect. Patients with additional shoulder pathologies such as partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tears, labral tears, or fraying and instability were not excluded. The 39 patients without a confirmed diagnosis of SAIS were diagnosed with glenohumeral instability, glenoid labral tear, rotator cuff tear, acromion-clavicular joint arthritis, and adhesive capsulitis. Patients were examined with five physical examination tests: the Neer, Hawkins-Kennedy, Painful arc, empty can (Jobe), and the external rotation resistance test. Surgical reference was the reference standard. Sensitivity and specificity were reported.

Somerville (2014) conducted a cohort study to determine the diagnostic validity of physical examination manoeuvres for rotator cuff lesions (defined as full-thickness tears, partial-thickness tears, and tendinosis of any of the three rotator cuff tendons: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis). Patients were recruited between May 2007 and November 2008 from two tertiary care orthopaedic centres. All participants were seen in the clinic for complaints about their shoulder (for the first time). Patients referred for shoulder replacement surgery were excluded. A total of 139 patients were included in the study, of which 101 were male and 38 were women, with a mean age of 46.0 years (SD 16.0). Physical examination tests were identified through a systematic review and consisted of the two supraspinatus tests (Jobe/empty can and full can), lift-off test, belly press test, internal rotation lag sign, lateral rotation lag sign, painful arc, Hawkins-Kennedy, and Neer test. The main reference standards were arthroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging with arthrogram (MRIa). The sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios were calculated to investigate whether combinations of the top tests provided stronger predictions of the presence or absence of disease.

Results

Two studies were included that reported on the combination of multiple physical examination tests for diagnosing SAPS.

Diagnostic outcome measures - sensitivity and specificity (crucial)

Michener (2009) reported the sensitivity and specificity for subacromial impingement syndrome (SAIS). The prevalence of SAIS was 29%: 16 out of 55 patients were confirmed via the golden standard of surgical findings with SAIS in isolation or in combination with another glenohumeral joint diagnosis. The 39 subjects who did not have a confirmed diagnosis of SAIS were diagnosed via surgical findings with (in order of frequency) glenohumeral instability, glenoid labral tear, rotator cuff tear, acromion-clavicular joint arthritis, and adhesive capsulitis. Table 1 depicts the diagnostic test accuracy results for individual tests as well as any test combination with a cut point of at least 3 out of 5 tests positive. The false-positive, false-negative, true-positive, and true-negative values with 95% CI and the NPV and PPV were manually calculated, using the sensitivity and specificity values and incidence numbers reported in the study, and added to the table.

Table 1. Diagnostic accuracy measures for impingement shoulder tests and any test combination.

N=55 subjects. Note: 3+ of 5 tests is the cut point for the discrimination of the presence or absence of SAIS using the 5 impingement tests. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; TP, true-positives; FP, false-positives; FN, false-negatives; TN, true-negatives; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Somerville (2014) reported the sensitivity and specificity for individual physical examination tests and a combination of tests for rotator cuff tears and tendinosis. However, to make a comparison between individual tests and a combination of multiple tests, these values must be reported. This was only the case for tests for the supraspinatus tendon, specifically for a full-thickness (FT) tear and FT and partial-thickness (PT) tear. Hence, only these results were subtracted from Somerville (2014).

Table 2 and 3 depict the diagnostic test accuracy results for the three individual tests as well as a combination of tests for the supraspinatus tendon. The study reported 53 patients with a FT tear, 14 patients with a PT tear, 16 patients with tendinosis and 56 patients without a RC lesion of the supraspinatus tear. The false-positive, false-negative, true-positive, and true-negative values with 95% CI and the NPV and PPV were manually calculated, using the sensitivity and specificity values and incidence numbers reported in the study, and added to the tables.

Note that for calculating the TP, FP, FN, TN, PPV and NPV values for the full-thickness and partial-thickness tears taken together, we assumed that the incidence numbers of the number of patients with a FT and PT tear could be added up (n=53 plus n=14)(Table 3).

Table 2. Sensitivity and specificity for three physical examination tests and a combination of these tests for the diagnosis of a full-thickness tear in the supraspinatus tendon

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; TP, true-positives; FP, false-positives; FN, false-negatives; TN, true-negatives; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Table 3. Sensitivity and specificity for three physical examination tests and a combination of these tests for the diagnosis of full-thickness and partial-thickness tears taken together in the supraspinatus tendon

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; TP, true-positives; FP, false-positives; FN, false-negatives; TN, true-negatives; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Pain (important)

No study reported pain.

Functionality (important)

No study reported functionality.

Return to work or leisure (important)

No study reported return to work or leisure.

Level of evidence of the literature

Diagnostic accuracy – sensitivity and specificity (crucial)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures sensitivity and specificity was downgraded by two levels to low because of wide confidence intervals around the point estimate (-2, imprecision).

Pain (important)

The level of evidence for pain could not be established, since none of the included studies reported this outcome.

Functionality (important)

The level of evidence for functionality could not be established, since none of the included studies reported this outcome.

Return to work or leisure (important)

The level of evidence for return to work or leisure could not be established, since none of the included studies reported this outcome.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the diagnostic accuracy for using a combination of multiple tests compared to a single test in diagnosing or ruling out of SAPS?

|

Patients |

patients with (suspected) SAPS, with exception of a subscapularis rupture |

|

Index test |

combination of multiple tests (for example empty can/neer/painful arc/exorotation againts resistance /Yocum/Hawkins) |

|

Comparator test |

solitary test (for example Hawkins) |

|

Reference standard |

imaging (ultrasound or MRI) or arthroscopy |

|

Outcomes |

pain, functionality, return to work or leisure, diagnostic test accuracy measures (sensitivity, specificity) |

|

Timing and setting |

outpatient orthopedic consultation |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered diagnostic test accuracy measures as critical outcome measure for decision making; and pain, functionality, and return to work or leisure as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the guideline development group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Due to the diagnostic nature of this question, no minimal clinically (patient) important difference was specified.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 2008 until February 21th, 2023.The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 629 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Patients with suspected SAPS

- A combination of diagnostic tests for SAPS compared to a single test for the diagnosis of SAPS

- Imaging tests (ultrasound or MRI) or arthroscopy as reference standard

- Pain, functionality, sensitivity and specificity as outcome measures

- Case-control studies were not included

Fifteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, thirteen studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Consigliere P, Haddo O, Levy O, Sforza G. Subacromial impingement syndrome: management challenges. Orthop Res Rev. 2018 Oct 23;10:83-91. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S157864. PMID: 30774463.

- Daghir AA, Sookur PA, Shah S, Watson M. Dynamic ultrasound of the subacromial-subdeltoid bursa in patients with shoulder impingement: a comparison with normal volunteers. Skeletal Radiol. 2012 Sep;41(9):1047-53. doi: 10.1007/s00256-011-1295-z. Epub 2011 Oct 14. PMID: 21997670.

- Ferenczi A, Ostertag A, Lasbleiz S, Petrover D, Yelnik A, Richette P, Bardin T, Orcel P, Beaudreuil J. Reproducibility of sub-acromial impingement tests, including a new clinical manoeuver. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2018 May;61(3):151-155. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2018.01.005. Epub 2018 Feb 13. PMID: 29452331.

- Girish G, Lobo LG, Jacobson JA, Morag Y, Miller B, Jamadar DA. Ultrasound of the shoulder: asymptomatic findings in men. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Oct;197(4):W713-9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.6971. PMID: 21940544.

- Gismervik SØ, Drogset JO, Granviken F, Rø M, Leivseth G. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test performance. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 Jan 25;18(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1400-0. PMID: 28122541 Free PMC article. Review.

- Jeremy S Lewis, Karen McCreesh, Eva Barratt, Eric J Hegedus, Julius Sim. Inter-rater reliability of the Shoulder Symptom Modification Procedure in people with shoulder pain. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016 Nov 11;2(1):e000181. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000181. eCollection 2016. PMID: 27900200 PMCID: PMC5125418 DOI: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000181

- Lee CK, Itoi E, Kim SJ, Lee SC, Suh KT. Comparison of muscle activity in the empty-can and full-can testing positions using 18 F-FDG PET/CT. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014 Oct 1;9:85. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0085-4. PMID: 25269645; PMCID: PMC4189674.

- Michener, L. A. and Walsworth, M. K. and Doukas, W. C. and Murphy, K. P. Reliability and Diagnostic Accuracy of 5 Physical Examination Tests and Combination of Tests for Subacromial Impingement. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2009; 90 (11) :1898-1903.

- Sean P Riley, Jason K Grimes, Adri T Apeldoorn, Riekie de Vet. Agreement and reliability of a symptom modification test cluster for patients with subacromial pain syndrome. Physiother Res Int. 2020 Jul;25(3):e1842. doi: 10.1002/pri.1842. Epub 2020 Apr 13. PMID: 32282115 DOI: 10.1002/pri.1842.

- Somerville, L. E. and Willits, K. and Johnson, A. M. and Litchfield, R. and LeBel, M. E. and Moro, J. and Bryant, D. Clinical Assessment of Physical Examination Maneuvers for Rotator Cuff Lesions. The American journal of sports medicine. 2014; 42 (8) :1911-1919.

- Veen EJD, Donders CM, Westerbeek RE, Derks RPH, Landman EBM, Koorevaar CT. Predictive findings on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with symptomatic acromioclavicular osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018 Aug;27(8):e252-e258. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.01.001. Epub 2018 Feb 28. PMID: 29501222.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for diagnostic test accuracy studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics

|

Index test (test of interest) |

Reference test

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Michener, 2009 |

Type of study: Diagnostic test accuracy study (prospective, blinded study design)

Setting and country: Orthopedic surgeon shoulder clinic

Funding and conflicts of interest: No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit on the authors or on any organization with which the authors are associated. |

Inclusion criteria: - Consecutive patients presenting with shoulder pain to an orthopedic surgeon’s office - patients had to report shoulder pain for at least 1 week, and shoulder pain had to be their primary complaint.

Exclusion criteria: Not reported.

Characteristics N=55 patients

Age,mean ± SD (range): 40.6 ± 15.1 years (range 18–83y)

Sex: 47 M/8 F

Average symptom duration 33.8 ± 48.9 months (range 2-230 months)

|

5 shoulder tests were compared to each other: Neer, Hawkins-Kennedy, painful arc, empty can (Jobe), and external rotation resistance test.

Neer test: the Neer test was performed with the examiner stabilizing the scapula with a downward force while fully flexing the humerus overhead maximally while applying overpressure. A positive test was reproduction of pain of the superior shoulder.

Hawkins-Kennedy test: performed by the examiner flexing the humerus and elbow to 90° and then maximally internally rotating the shoulder and applying overpressure. A positive test was reproduction of pain of the superior shoulder.

Painful arc: performed by asking the patient to actively abduct his/her shoulder and report any pain during abduction. If pain of the superior shoulder was noted between 60° and 120° of abduction, the test was considered positive.

Empty can test (Jobe test): performed by the examiner elevating the shoulder to 90° in the scapular plane (30°– 40° anterior to the coronal plane) and then placing the shoulder in internal rotation by asking the patient to rotate the shoulder so that his/her thumb was pointing toward the floor. The examiner then applied a downward directed forced at the wrist while the patient attempted to resist. A positive test was considered if weakness was detected of the involved shoulder as compared bilaterally.

External rotation resistance test: performed by placing the arm at the patient’s side and flexing their elbow to 90°. A medially directed force was exerted on the distal forearm to resist shoulder external rotation. A positive test was considered if weakness was detected of the involved shoulder as compared bilaterally.

Cut-off point(s): An ROC curve analysis for each physical examination test was used to calculate the AUC, which represents the probability that the test can discriminate between healthy and disease states. The AUC values range from 0 to 1, with an AUC of 1 indicating 100% probability that a given test can discriminate between healthy and SAIS.

The cut point for discrimination was 3 positive tests out of 5.

|

The operative findings were used as the reference standard, and the patients were classified as positive or negative for SAIS based on the surgical findings.

Description: The reference standard was determined via operative findings reported by an operative surgeon blinded to the clinical examination findings.

The intraoperative reference standard criteria for SAIS were the presence of any of the following: visually enlarged bursa, fibrotic appearing bursa, or degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon at the superficial aspect. Patients with additional shoulder pathologies such as partial or full-thickness rotator cuff tears, labral tears, or fraying and instability were not excluded.

|

After completion of the history and physical examination, the patients underwent an arthroscopic examination within an average of 2.6 months (+-2.7mo, range: 1d–8mo) after the clinical examination.

There were no missing values. |

Outcome measures and effect size

ROC curve analysis:

The cut point to discriminate between patients with and without SAIS was 3 positive tests out of 5 (AUC=0.79, 95% CI 0.66–0.92; P=0.001).

Diagnostic accuracy for any test combination (≥ 3 out of 5 positive):

Sens: 0.75 (95% CI 0.54-0.96) Spec: 0.74 (95% CI 0.61-0.88) LR+: 2.93 (95% CI 1.60-5.36) LR-: 0.34 (95% CI 0.14-0.80)

Posttest probabilities:

≥ 3 out of 5 positive: LR+= 54.4% < 3 out of 5 positive: LR- = 12.1%

|

Author’s conclusion:

The single tests of painful arc, external rotation resistance test, and empty can provide the best diagnostic utility and reliability. The Neer test has clinical utility to screen for SAIS but has only fair reliability. Also of diagnostic utility is the use of the cut point of 3+/5 tests, with 3 or more tests positive of 5 useful in confirming SAIS, whereas less than 3 positive of the 5 tests is helpful in decreasing the likelihood of SAIS. |

|

Somerville, 2014 |

Type of study: Diagnostic test accuracy study

Setting and country: Two tertiary orthopaedic clinics

Funding and conflicts of interest: One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: This study received funding through an internal source that paid for research assistant time to collect data. |

Inclusion criteria: Participants who came to the clinic for their first consultation for complaints about their shoulder

Exclusion criteria: Patients who were referred for shoulder replacement surgery.

Characteristics N= 139

Mean age ± SD: 46.0 ± 16.0 years

Sex: 101 M / 38 F

The average supraspinatus tendon tear size was 2.4 ± 1.4 cm from anterior to posterior (range, 0.5-6 cm). |

We included the following physical examination tests: (1) supraspinatus test (Jobe test) and full can test (supraspinatus tears); (2) lift-off test, belly press test, and internal rotation lag sign (subscapularis tears); (3) lateral rotation lag sign (infraspinatus tears); and (4) painful arc, Hawkins-Kennedy sign, and Neer impingement sign (tendinosis).

Patients for whom the physician faced uncertainty in the diagnosis (ie, clinician rated as above the testing but below the treatment threshold) remained as part of the study group for that diagnosis, and the physical examination maneuvers specific to that diagnosis were then performed.

Cut-off point(s): |

Although most patients went on to have surgery, some were not referred for surgery or opted out. These patients underwent a standardized MRIa as the reference standard. All MRIs had an intra-articular injection of gadolinium done under fluoroscopy. The strength of the MRI magnet was 1.5 tesla, and the MRI sequences were all protocoled to provide optimal imaging of the lesions being investigated (axial T1-weighted and T1-weighted fat saturated [fat sat], coronal T1-weighted and T1-weighted fat sat, proton density fat sat, T2-weighted fat sat, and sagittal proton density fat sat sequences). All MRIs were done at a university center by radiologists with substantial expertise in musculoskeletal imaging. Images were interpreted by a fellowship-trained radiologist who was blinded to the physical examination results. |

Time between the index test en reference test: Not specified. Incomplete outcome data |

Outcome measures and effect size

Diagnostic validity of the combination of physical examination manaeuvers:

Supraspinatus tears (includes supraspinatus test, full can test, and lateral rotation lag sign) Full thickness tears At least one positive Sens: 73.6 (95% CI 60.4-83.6) Spec: 57.5 (95% CI 46.6-67.7) +LR: 1.73 -LR: 0.46

At least two positive Sens: 62.3 (95% CI 48.8-74.1) Spec: 73.8 (95% CI 63.2-82.1) +LR: 2.37 -LR: 0.51

All three positive Sens: 18.9 (95% CI 10.6-31.4) Spec: 98.8 (95% CI 93.3-99.8) +LR: 15.09 -LR: 0.82

All tears At least one positive Sens: 67.2 (95% CI 55.3-77.2) Spec: 57.6 (95% CI 45.6-68.8) +LR: 1.58 -LR: 0.57

At least two positive Sens: 55.2 (95% CI 43.4-66.5) Spec: 74.2 (95% CI 62.6-83.3) +LR: 2.14 -LR: 0.60

All three positive Sens: 14.9 - 8.3-25.3) Spec: 98.5 (95% CI 91.9-99.7) +LR: 9.85 -LR: 0.86

Supraspinatus tears with the lateral rotation lag sign removed Full thickness tears At least one positive Sens: 73.6 (95% CI 60.4-83.6) Spec: 57.5 (95% CI 46.6-67.7) +LR: 1.73 -LR: 0.46

Two positive Sens: 62.3 (95% CI 48.8-74.1) Spec: 75.8 (95% CI 64.1-83.0) +LR: 2.46 -LR: 0.51

All tears At least one positive Sens: 67.2 (95% CI 55.3-77.2) Spec: 57.6 (95% CI 45.6-68.8) +LR: 1.58 -LR: 0.57

Two positive Sens: 55.2 (95% CI 43.4-66.5) Spec: 75.8 (95% CI 64.2-84.5) +LR: 2.28 -LR: 0.59

Tendinosis (includes painful arc, Neer test, and Hawkins-Kennedy test) Tendinosis At least one positive Sens: 75.0 (95% CI 50.5-89.8) Spec: 21.7 (95% CI 15.2-29.9) +LR: 0.96 -LR: 1.15

At least two positive Sens: 62.5 (95% CI38.6-81.5) Spec: 38.3 (95% CI 30.1-47.3) +LR: 1.01 -LR: 0.98

All three positive Sens: 31.3 (95% CI 14.2-55.6) Spec: 62.5 (95% CI 53.6-70.7) +LR: 0.83 -LR: 1.10

All disease At least one positive Sens: 80.5 (95% CI 70.6-87.6) Spec: 25.9 (95% CI 16.1-38.9) +LR: 1.09 -LR: 0.75

At least two positive Sens: 68.3 (95% CI 57.6-77.4) Spec: 48.2 (95% CI 35.4-61.2) +LR: 1.32 -LR: 0.66

All three positive Sens: 45.1 (95% CI 34.8-55.9) Spec: 75.9 (95% CI 63.1-85.4) +LR: 1.87 -LR: 0.72

Full thickness tears At least one positive Sens: 88.5 (95% CI 77.0-94.6) Spec: 28.6 (95% CI 20.0-39.0) +LR: 1.24 -LR: 0.40

At least two positive Sens: 73.1 (95% CI 59.8-83.2) Spec: 45.2 (95% CI 35.0-55.9) +LR: 1.33 -LR: 0.60

All three positive Sens: 51.9 (95% CI 38.7-64.9) Spec: 72.6 (95% CI 62.3-81.0) +LR: 1.90 -LR: 0.66

|

Authors’ conclusion: No test in isolation is sufficient to diagnose a patient with rotator cuff damage. A combination of tests improves the ability to diagnose damage to the rotator cuff. It is recommended that the internal rotation and lateral rotation lag signs be removed from the gamut of physical examination tests for supraspinatus and subscapularis tears. |

Risk of bias assessment for diagnostic accuracy studies (QUADAS II, 2011)

|

Study reference |

Patient selection

|

Index test |

Reference standard |

Flow and timing |

Comments with respect to applicability |

|

Michener, 2009 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes, but 3 patients refused to participate, and 7 did not undergo the reference standard.

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? 7 patients refused to undergo the reference standard, these were excluded.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes (Each clinician independently performed a standardized history and physical examination and was blinded to each other’s findings and without knowledge of any imaging studies.)

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes (The reference standard was determined via operative findings reported by an operative surgeon blinded to the clinical examination findings.)

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Yes

Did all patients receive a reference standard? All patients who were included received the refence standard

Did patients receive the same reference standard? Yes

Were all patients included in the analysis? Yes

|

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

||

|

Somerville, 2014 |

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled? Yes, but 15 patients refused to undergo one of the reference standard tests or canceled their test.

Was a case-control design avoided? Yes

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions? 15 patients refused to undergo the reference standard, these were excluded.

|

Were the index test results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard? Yes (We ensured that the physician performing the physical examination tests did not review any available imaging studies or reports before evaluating the patient.)

If a threshold was used, was it pre-specified? Yes

|

Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition? Yes (There is good evidence to suggest that MRIa is a comparable reference standard to arthroscopy, and MRIa has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific for detecting both rotator cuff and labral injuries)

Were the reference standard results interpreted without knowledge of the results of the index test? Yes (The surgeon performed a systematic diagnostic arthroscopy, taking care to visualize and evaluate the integrity of all pertinent anatomy, and was required to complete a standardized checklist documenting any findings for each structure (Appendix 2, available online). We developed this to minimize differences between surgeons due to variations in methods of examination and to minimize any detection bias should the clinician recall the physical examination or imaging at the time of interpreting the surgical examination. Images were interpreted by a fellowship-trained radiologist who was blinded tow the physical examination results.)

|

Was there an appropriate interval between index test(s) and reference standard? Unclear

Did all patients receive a reference standard? All patients who were included received the refence standard

Did patients receive the same reference standard? No, but: “There is good evidence to suggest that MRIa is a comparable reference standard to arthroscopy, and MRIa has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific for detecting both rotator cuff and labral injuries.”

Were all patients included in the analysis? Unclear |

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question? No

Are there concerns that the index test, its conduct, or interpretation differ from the review question? No

Are there concerns that the target condition as defined by the reference standard does not match the review question? No

|

|

|

CONCLUSION: Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION: Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW

|

CONCLUSION: Could the reference standard, its conduct, or its interpretation have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

CONCLUSION Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

RISK: LOW |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Cotter, E. J. and Hannon, C. P. and Christian, D. and Frank, R. M. and Bach, B. R. Comprehensive Examination of the Athlete's Shoulder. Sports health. 2018; 10 (4) :366-375 |

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests) |

|

Beaudreuil, J. and Nizard, R. and Thomas, T. and Peyre, M. and Liotard, J. P. and Boileau, P. and Marc, T. and Dromard, C. and Steyer, E. and Bardin, T. and Orcel, P. and Walch, G. Contribution of clinical tests to the diagnosis of rotator cuff disease: A systematic literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2009; 76 (1) :15-19 |

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests) |

|

Alqunaee, M. and Galvin, R. and Fahey, T. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for subacromial impingement syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012; 93 (2) :229-236 |

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests) |

|

Dakkak, A. and Krill, M. K. and Krill, M. L. and Nwachukwu, B. and McCormick, F. Evidence-Based Physical Examination for the Diagnosis of Subscapularis Tears: A Systematic Review. Sports health. 2021; 13 (1) :78-84 |

Wrong P (subscapularis tears) |

|

Hanchard NC, Lenza M, Handoll HH, Takwoingi Y. Physical tests for shoulder impingements and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;2013(4):CD007427. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007427.pub2. PMID: 23633343; PMCID: PMC6464770. |

Wrong study design (study protocol) |

|

Rigsby, Ruel and Sitler, Michael and Kelly, John D. Subscapularis tendon integrity: an examination of shoulder index tests. Journal of athletic training. 2010; 45 (4) :404-6 |

Wrong study design (commentary) |

|

Jain, N. B. and Luz, J. and Higgins, L. D. and Dong, Y. and Warner, J. J. and Matzkin, E. and Katz, J. N. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Special Tests for Rotator Cuff Tear: The ROW Cohort Study. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2017; 96 (3) :176-183

|

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests)

|

|

Kappe, T. and Sgroi, M. and Reichel, H. and Daexle, M. Diagnostic performance of clinical tests for subscapularis tendon tears. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2018; 26 (1) :176-181

|

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests)

|

|

Verry, Christian and Fernando, Sheran Rotator Cuff Disease: Diagnostic Tests. American family physician. 2016; 94 (11) :925-926 |

Wrong study design (question and answer)

|

|

Yazigi Junior, J. A. and Anauate Nicolao, F. and Matsunaga, F. T. and Archetti Netto, N. and Belloti, J. C. and Sugawara Tamaoki, M. J. Supraspinatus tears: predictability of magnetic resonance imaging findings based on clinical examination. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2021; 30 (8) :1834-1843 |

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests)

|

|

Phillips, Nick Tests for diagnosing subacromial impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease. Shoulder & elbow. 2014; 6 (3) :215-21

|

Wrong study design (narrative review)

|

|

Lädermann, A. and Meynard, T. and Denard, P. J. and Ibrahim, M. and Saffarini, M. and Collin, P. Reliable diagnosis of posterosuperior rotator cuff tears requires a combination of clinical tests. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2021; 29 (7) :2118-2133

|

Wrong comparison (not multiple tests, just single tests)

|

|

Hegedus, E. J. and Goode, A. P. and Cook, C. E. and Michener, L. and Myer, C. A. and Myer, D. M. and Wright, A. A. Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. British journal of sports medicine. 2012; 46 (14) :964-978

|

Review comparing multiple combinations of factors and tests from individual studies (see table 4). However, these were all not the right tests/factors/pathologies or the individual study was already included. |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 03-02-2025

Laatst geautoriseerd : 03-02-2025

Geplande herbeoordeling : 03-02-2028

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het herzien van de richtlijnmodules is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met Subacromiaal Pijnsyndroom van de Schouder (SAPS).

Werkgroep

dr. J.J.A.M (Jos) van Raaij, orthopedisch chirurg Martiniziekenhuis Groningen, NOV (voorzitter)

dr. C.P.J. (Cornelis) Visser, orthopedisch chirurg Alrijne en Eisenhower Kliniek, NOV

dr. F.O. (Okke) Lambers Heerspink, orthopedisch chirurg VieCuri Medisch Centrum, NOV

dr. E.J.D. (Bart Jan) Veen, orthopedisch chirurg Medisch Spectrum Twente, NOV

dr. O. (Oscar) Dorrestijn, orthopedisch Chirurg Sint Maartenskliniek, NOV

dr. M.J.C. Maarten Leijs, orthopedisch chirurg Reinier Haga Orthopedisch Centrum , NOV

dr. D. (Dennis) van Poppel, manueel therapeut, sportfysiotherapeut PECE Zorg, Fontys Paramedisch, KNGF

drs. P.A. (Peter) Stroomberg, radioloog, Isala, NVvR

dr. R.P.G. (Ramon) Ottenheijm, huisarts, vakgroep huisartsgeneeskunde, Universiteit Maastricht, NHG

dr. J.W. (Jan Willem) Kallewaard, anesthesioloog Rijnstate, NVA

drs. T.J.W. (Tjerk) de Ruiter, revalidatiearts De Ruiter Revalidatie, VRA

dr. H.A. (Henk) Martens, reumatoloog Sint Maartenskliniek, NVR

Klankbordgroep

drs. R.J. (René) Naber, Bedrijfsarts arbodienst Amsterdam UMC, NVAB

drs. Y.B. (Yvonne) Suijkerbuijk, Arts-onderzoeker Amsterdam UMC en verzekeringsarts UWV, NVVG

Met ondersteuning van

dr. J.G.M. (Jacqueline) Jennen, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (oktober 2023 tot mei 2024)

drs. T. (Tessa) Geltink, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot mei 2024)

drs. F.M. (Femke) Janssen, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (tot oktober 2023, vanaf mei 2024)

dr. M.S. (Matthijs) Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (vanaf mei 2024)

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Werkgroep

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Van Raaij (voorzitter) |

Voorzitter werkgroep |

Orthopedisch chirurg, wetenschappelijk medewerker (stichting orthoresearch noord) Martiniziekenhuis Groningen (onbezoldigd). Bestuurslid werkgroep schouder/elleboog NOV (onbezoldigd) Lid registratie adviesraad (RAR) LROI (Landelijke Registratie Orthopedische Implantaten) (onbezoldigd). Lid LEARN, (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) (onderzoek naar opleiding/onderwijs) (onbezoldigd). Cursusleider vaardigheidstraining voor aios orthopedie (Techmed Centre, University of Twente) (onbezoldigd). Voorzitter werkgroep herziening richtlijn SAPS (FMS, kennisinstituut).

Lid werkgroep richtlijn chronische instabiliteit schouder (FMS, kennisinstituut)

Voorzitter cluster richtlijnen bovenste extremiteit (FMS,kennisinstituut)

Lid werkgroep ontwikkeling richtlijn schouderklachten, KNGF (fysiotherapie)

|

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Visser

|

Orthopedisch chirurg Alrijne |

Orthopedisch chirurg Eisenhowerkliniek; Lid wetenschappelijke adviesraad (WAR) LROI (Landelijke Registratie Orthopedische Implantaten) (onbezoldigd); Lid kascommissie van de NOV (onbezoldigd) |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

|

Orthopedisch chirurg VieCuri Medisch Centrum

|

Commissie van onderzoek VieCuri (onbetaald) ] Lid wetenschapscommissie VieCuri (onbetaald) Voorzitter BELG (Bovenste Extremiteit Limburgs genootschap) (onbetaald)

|

Presentatie orthopedische firma (Arthrex) betreffende proximale humerusfracuur (betaald)

Extern gefinancieerd onderzoek (Financier, (inhoud)): Arthrex en Fons Wetenschap Innovatie Viecuri (optimale positionering glenoid bij revers schouderprothese), Fons wetenschap innovatie Viecuri (Nabehandeling schouderprothese middels app), Fonds Wetenschap Innovatie Viecuri (Voorkomen van cristallopathie bij patienten met een degeneratieve rotator cuff ruptuur). |

Geen restricties, onderwerp van extern gefinancierd onderzoek valt buiten het bestek van de richtlijn

|

|

Veen

|

Orthopedisch chirurg, Medisch Spectrum Twente |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Dorrestijn

|

Orthopedisch chirurg |

Dienstverband Sint Maartenskliniek - echter geen direct financieel voordeel |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Leijs

|

Clubarts Excelsior en orthopedisch chirurg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Van Poppel

|

Manueel therapeut, sportfysiotherapeut, bewegingswetenschapper, docent, onderzoeker bij PECE Zorg, Schouder Expertise Centrum en Fontys Hogescholen. |

Zelfstandig docent, auteur, onderzoeker, betaald.

Docent Master Opleiding Sportfysiotherapie Hogeschool Rotterdam, betaald.

Lid werkgroep ontwikkeling richtlijn schouderklachten, KNGF (fysiotherapie).

Auditeur Health Care Auditing, betaald.

Lid Regionaal Tuchtcollege Gezondheidszorg, betaald. |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Deelname vanaf 09-10-2023 |

Tot 31-10-2024: Fellow Radioloog, Rijnstate Ziekenhuis

Vanaf 01-11-2024: Radioloog Isala

|

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Koen

Deelname t/m 09-10-2023 |

Radioloog bij het Meander Medisch Centrum, Screeningsradioloog bevolkingsonderzoek borstkanker. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Ottenheijm

|

Universitair docent; Vakgroep Huisartsgeneeskunde, Universiteit Maastricht; Kaderhuisartsbewegingsapparaat: werkzaam als ZZPer voor MCC Omnes, Pluspunt MC en ZBC Optimus Orthopedie |

Voorzitter Stichting Optimus Klinieken (ZBC) (onbetaald) Medisch Directeur van Optimus Orthopedie BV (onbetaald) Bestuurder van de NHG-expertgroep Het Beweegkader (vereniging van kaderhuisartsen bewegingsapparaat) t/m juni 2022.

|

Werkzaam als ZZP kaderhuisarts op 1,5 lijnspoli's en in een ZBC orthopedie, waar zorg voor schouderpatienten wordt geleverd. Mede-aandeelhouder Optimus Orthopedie BV

Mede-aanvrager van een door ZonMW gefinanceerd doelmatigheidsonderzoek schouderklachten in de huisartspraktijk (Hoofdaanvrager werkzaam bij Erasmus MC) |

Geen restricties

|

|

Kallewaard

|

Anesthesioloog, Rijnstate Ziekenhuis |

Betrokken bij andere richtlijnen: bbc nva sectie pijn nva hoofd clusterpijn deelnemer |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek (Financier, inhoud): Boston Scientific (Neuromodulatie en endometriose), Saluda (neuromodulatie psps2), Dtm (neuromodulatie virgin back). |

Geen restricties, onderwerp van extern gefinancierd onderzoek valt buiten het bestek van de richtlijn

|

|

De Ruiter

|

Revalidatiearts bij De Ruiter Revalidatie |

Rotterdam Knowledge Ambassador, Onbetaald.

Adviseur Stichting Mobiliteit voor Gehandicapten, Onbetaald.

Oprichter Perpetual Prosthetics, Onbetaald.

Lid Membership Committee, International Society on Prosthetics and Orthotics, onbetaald. |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Martens

|

Reumatoloog bij de Sint Maartenskliniek |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

Klankbordgroep

|

Klankbordgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Naber |

Bedrijfsarts AUMC

|

Secretaris NVAB werkgroep Bedrijfsartsen in de Zorg (onbetaald)

|

Geen |

Geen restricties

|

|

Suijkerbuijk |

Arts-onderzoeker (promovenda) Kenniscentrum Verzekeringsgeneeskunde, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC (betaald)

|

-Lid commissie wetenschap NVVG: beoordelen en deelname aan ontwikkeling van richtlijnen. Momenteel deelname aan ontwikkeling multidisciplinaire richtlijn Depressie (Trimbos) (onbetaald)

|

promotieonderzoek gefinancierd door UWV

|

Geen restricties

|

Met ondersteuning van

|

Janssen |

Junior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen acties |

|

Ruiter |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen acties |

|

Geltink |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen acties |

|

Jennen |

Adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen acties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference (knelpuntenanalyse). Het verslag hiervan is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd om te beoordelen of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Diagnostische testen voor SAPS (herzien/aanvulling op module) |

Geen substantiële financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn, volgt ook uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van het zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 3.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met SAPS. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door de IGJ, NFU, NHG, NVZ, PF NL, STZ, V&VN, NAPA, ZiNL, ZKN, ZN, VIG, NOV, KNGF, NVvR, NHG, NVA, PFNL, VRA, NVR, NVAB, en Verzekeringsgeneeskundigen, via een knelpuntenanalyse (invitational conference). Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een [random-effects model]. [Review Manager 5.4] werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zou de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.