Verlaging valrisico bij thuiswonende ouderen

Uitgangsvraag

Welke valrisico verlagende interventies zijn effectief bij thuiswonenden?

Aanbeveling

Verricht een multifactoriële interventie bij thuiswonende vallers gericht op geidentificeerde valrisicofactoren. Gezien de sterke bewijskracht ten aanzien van bewegingsinterventies dient een multifactoriële val preventieve interventie ten minste één beweegcomponent te bevatten.

Beperken tot een enkelvoudige interventie kan overwogen worden bij eenmalige vallers zonder bijkomende factoren die zich niet met een acute val presenteren. Indien gekozen wordt voor een enkelvoudige interventie, dient dit een beweeginterventie te zijn, tenzij een specifieke andere valrisicofactor is vastgesteld.

Vraag uitdrukkelijk na wat de wensen zijn van de patiënt zijn en bespreek de mogelijkheden. Beslis samen met de patiënt wat de meest geschikte interventie is in zijn/haar situatie. Dit verhoogt de therapietrouw.

Verwerk in de multifactoriële interventie voor thuiswonende vallers de positief gescoorde valrisicofactoren en overweeg minimaal de volgende items:

|

Categorie |

Interventie |

|

Beweging |

Kies voor de interventie betreffende beweeginterventies een op (fysio- of oefentherapeutische) assessment gebaseerde vorm, bij voorkeur één met meerdere categorieën (individueel dan wel in groepsverband). Tai Chi kan overwogen worden. |

|

Cardiovasculaire aandoeningen (incl. orthostatische hypotensie) |

Overweeg orthostase adviezen (zie ook de module ‘Valpreventie bij orthostatische hypotensie’) en andere cardiovasculaire interventies conform ESC-guidelines. |

|

Kennisoverdracht |

Overweeg kennisoverdracht aan patiënten ten aanzien van valpreventie (waaronder beweeg- en alcoholadviezen) (zie ook de module ‘Compliantie van ouderen aan valpreventie’) |

|

Medicatieafbouw (cardiovasculaire medicatie) |

Overweeg (begeleid) afbouwen van cardiovasculaire medicatie, neem hierbij de indicatie en patiënt preferente wensen (behandeldoelen) in ogenschouw en betrek de hoofdbehandelaar (zie ook de richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij ouderen). |

|

Medicatieafbouw (psychofarmaca) |

Bouw psychofarmaca af om het valrisico te verlagen. Betrek hierbij de hoofdbehandelaar. |

|

Omgeving |

Voer als onderdeel van de multifactoriële interventie een persoonsomgevingsinterventie uit, of verwijs hiervoor naar de ergotherapeut voor een evidence based aanpak. |

|

Onderliggende ziektes/aandoeningen |

Voer specifieke interventies uit |

|

Operatief (cataract OK, pacemakerimplantatie bij cardioinhibitoire sinus caroticus overgevoeligheid) |

Adviseer cataractoperatie (van het eerste oog) bij vallers met cataract Adviseer pacemakerimplantatie bij cardioinhibitoire sinus caroticus overgevoeligheid |

|

Psychologische interventies |

Voer specifieke interventies uit |

|

Schoeisel/Voetproblemen |

Adviseer gebruik van veilig schoeisel, overweeg inschakelen van podiatrie |

|

Vertebril |

Adviseer gebruik van aparte vertebril (in plaats van multifocaal bril) voor buitenactiviteiten bij vallers die regelmatig zelfstandig buiten komen |

|

Vitamine D-suppletie |

Geef vitamine D-suppletie (800IE per dag) indien het vitamine D verlaagd is. Laad bij een ernstige deficiëntie (vitamine D < 30nmol/L) zo nodig op tot de normaalwaarde is bereikt. |

|

Vloeistof of voedingstherapie |

Behandel ondervoeding en dehydratie |

Overwegingen

Een val is een symptoom van onderliggende aandoeningen en/of ziekten met over het algemeen meerdere onderliggende risicofactoren tegelijkertijd. Zodoende dient een valrisicobeoordeling en bijbehorende interventie over het algemeen multifactorieel van aard te zijn. Belangrijke behandelbare valrisicofactoren zijn gestoorde mobiliteit, gebruik van valrisico verhogende medicatie, valangst, vitamine D te kort, omgevingsfactoren, onveilig schoeisel en slechtziendheid. Voor interventies gericht op cognitie of stemming, slechthorendheid en urine-incontinentie, is voor thuiswonenden geen bewijsvoering ten aanzien van effectiviteit als individuele interventie. Als component van de multifactoriële interventie kan het wel degelijk zinvol zijn om deze mee te nemen.

In het algemeen kan voor de multifactoriële interventie aangehouden worden dat gevonden afwijkingen worden behandeld. Gezien de sterke bewijskracht ten aanzien van bewegingsinterventies dient een multifactoriële valpreventieve interventie ten minste één beweegcomponent te bevatten (Sherrington, 2008). Daarnaast dienen de volgende interventies in ieder geval overwogen te worden: aanvullende beweeginterventies, verminderen van valangst, omgevingsinterventies, optimaliseren van de visus (cataract OK, aparte vertebril buiten), vitamine D (indien deficiënt), afbouwen van valrisico verhogende medicatie, patiënteducatie waaronder gebruik veilig schoeisel en orthostase adviezen. Ondanks dat algemene adviezen over beweging (beweeg dagelijks minaal 30 minuten laag intensief) en alcoholgebruik (beperk alcoholgebruik, bij voorkeur volledig staken) niet uit de evidence apart naar voren komen, gelden deze adviezen ook thuiswonenden met een verhoogd valrisico.

Patiënteducatie is voor het slagen van de multifactoriële interventie essentieel. Het doel is om inzicht te geven in de relatie tussen de risicofactoren en vallen om zodoende de compliantie te verbeteren. Wees ervan bewust dat autonomie en onafhankelijkheid van patiënten van grote waarde is. Soms is dit zwaarwegender dan het valrisico aan te pakken. Nederlandse trials hebben laten zien dat juist de (beperkte) compliantie de effectiviteit van de multifactoriële interventie in de weg lijkt te staan. Om compliantie te optimaliseren, is het belangrijk om in een gefaseerde aanpak van achtereenvolgens bewustwording van het valrisico, kennis ten aanzien van valrisicofactoren en toepassing van valpreventieve maatregelen aan de orde te laten komen. Hierbij is het belangrijk dat de voordelen van een interventie duidelijk zijn voor de patiënt en zijn/haar naasten. En eventueel aanwezige valangst en schaamte dienen te worden geïdentificeerd. Dit zorgt ervoor dat ouderen gemotiveerd zijn en daadwerkelijk maatregelen gaan nemen. Meestal vraagt dit om meerdere vervolgconsulten (zie ook de module ‘Compliantie van ouderen aan valpreventie’).

Ten aanzien van beweegprogramma’s blijkt uit de literatuur dat beweegprogramma’s die zich richten op balans, spierkracht en mobiliteit het meest effectief zijn om valrisico te verkleinen. Dit geldt zowel voor groepslessen als voor thuisprogramma’s. Over het algemeen is bij groepslessen aanpak van valangst een geïntegreerd onderdeel van het programma. Belangrijke onderdelen zijn daarnaast conditie, veilig loophulpmiddelgebruik en veilige transfers. Zowel individuele als groepsprogramma’s zijn effectief. Bij voorkeur wordt in overleg met een fysiotherapeut of een oefentherapeut een geïndividualiseerd beweegadvies gegeven onder andere omdat een beweeginterventie vooral effectief is als de oefeningen voldoende uitdagingen bieden. Ook hier dient zorgvuldig gezocht te worden naar iets waarbij een hoge therapietrouw te verwachten is. Het is hierbij belangrijk om aan te sluiten bij individuele doelen en motiverende/belemmerende factoren.

Ten aanzien van omgevingsinterventies blijkt uit het onderzoek van Pighills (2011) dat een persoon-omgevingsinterventie uitgevoerd door ergotherapeuten effectiever is dan dezelfde interventie uitgevoerd door hiertoe getrainde thuiszorgmedewerkers. Een ergotherapeutisch valpreventief consult bestaat uit het in kaart brengen van het motorisch en cognitief handelen binnen de context van de eigen omgeving door ergotherapeut (hiervoor wordt naar de richtlijn Valpreventie van de Ergotherapeuten verwezen) Minimaal wordt een checklist voor beoordeling thuis door de patiënt geadviseerd.

Ten aanzien van afbouw van valrisicoverhogende medicatie dient in ieder geval afbouw van psychotrope medicatie (sedativa) worden overwogen. Ten aanzien van cardiovasculaire medicatie is bewijsvoering beperkter, maar er zijn aanwijzingen dat een geïndividualiseerde afbouw effectief en veilig is (zie ook de module ‘Effect medicijnen op valrisico ouderen’). Een recente Nederlandse studie naar effectiviteit van medicatie afbouw liet geen effect van deze individuele interventie zien, opvallend hierbij was dat aan het einde van de studie het gebruikte aantal valrisico verhogende medicijnen gemiddeld hoger was als bij start. Dit benadrukt het belang van samenwerken in de keten bij valpreventieve interventies, zoals ook ondersteund wordt door de opzet van een bewezen effectieve medicatie afbouw studie onder leiding van apothekers, waar samenwerking met voorschrijvers goed was georganiseerd. De negatieve Nederlandse studie onderstreept eveneens het belang van goede patiënteducatie en betrokkenheid om compliantie te maximaliseren (zie ook de modules ‘Compliantie van ouderen aan valpreventie’ en ‘Organisatie van zorg bij valpreventie ouderen’). Bij medicatie afbouw wordt gekeken naar veilige opties voor verminderen of staken van valrisico verhogende medicatie. Indien aanwezig wordt deze zo mogelijk gestaakt, of vervangen door een veiliger middel. Ook kan dosisverlaging of wijziging van moment van inname leiden tot verlaging van het valrisico.

Voor vitamine D geldt dat een sufficiënte status een bijdrage heeft aan een betere botkwaliteit en daarnaast heeft het een gunstig effect op spierkracht en balans. Aanvullend gebruik met een streefwaarde van >60 nmol/l in het bloed leidt tot een verlaging van het valrisico. Over het algemeen is 800 IE per dag hiervoor afdoende, tenzij er sprake is van een ernstige vitamine D-deficiëntie (<30 nmol/l), dan is opladen wenselijk om de beoogde streefspiegel sneller te behalen. Dit kan bijvoorbeeld door het te kort te berekenen met behulp van de volgende formule: 40 x (75-gemeten vitamine D-spiegel) x lichaamsgewicht (Kg) en dit toe te dienen in porties van 25.000 IE per week oraal. Van belang is om niet te hoog te doseren, aangezien dit juist het valrisico weer kan verhogen evenals een verhoging van het cardiovasculair risico (van Dijk, 2015).

Bij laagrisicopatiënten kan een enkelvoudige interventie overwogen worden, dit betreft over het algemeen een mobiliteitsinterventie.

Al met al: bij de verschillende interventies is het belangrijk om bij de persoon zelf aandacht te hebben voor: zijn/haar autonomie, zoveel mogelijk aansluiten bij de wensen en behoefte van de cliënt, een goede uitleg over het belang van valpreventie en zorg te dragen voor een goede motivatie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Valpreventieve interventies bij thuiswonenden kunnen onderverdeeld worden in enkelvoudige, multipele en multifactoriële interventies. Omdat bij vallen over het algemeen meerdere factoren tegelijkertijd een rol spelen, heeft een multifactorieel preventieprogramma de meeste kans van slagen. Veel studies tonen aan dat het valrisico, dat wil zeggen het aantal valincidenten, bij ouderen effectief gereduceerd kan worden, met circa 40% (Gillespie, 2012; Karlsson, 2013). Uit onderzoek blijkt dat ten aanzien van valpreventie de meeste maatregelen alleen effectief zijn als ze in combinatie met andere maatregelen worden uitgevoerd. Enkelvoudige interventies worden wel toegepast en zijn over het algemeen gericht op optimalisering van de mobiliteit. Enkelvoudige interventies en worden bij voorkeur alleen uitgevoerd bij laagrisicopatiënten. Bij onbegrepen of recidiverend vallen wordt veelal een multifactoriële interventie verricht. Er is nog geen zekerheid ten aanzien van de optimale inhoud van de multifactoriële interventie, deze is verschillend in de verschillende studies. Dit vindt zijn vertaalslag in de praktijk, waarbij er regionale verschillen zijn, vaak afhankelijk van de omgeving waar de interventie wordt aangeboden (1e versus 2e lijn). Een belangrijke belemmering voor effectiviteit van de (multifactoriële) interventie is compliantie.

Conclusies

1. Lichamelijke oefeningen versus controle

Aantal vallers

|

Laag GRADE |

Groepsverband: Meerdere categorieën lichamelijke oefeningen Lichamelijke oefeningen in groepsverband bestaande uit meerdere categorieën verlagen het aantal vallers onder thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Gianoudis, 2014; Kim, 2014; Patil, 2015) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Individueel: Meerdere categorieën lichamelijke oefeningen Individueel afgestemde lichamelijke oefeningen bestaande uit meerdere categorieën verlagen het aantal vallers onder thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Gleeson, 2015; Suttanon, 2013) |

|

Laag GRADE |

Tai Chi (groepsverband) Tai Chi oefeningen in groepsverband verlagen het aantal vallers onder thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012) |

Valfrequentie

|

Matig GRADE |

Groepsverband: Meerdere categorieën lichamelijke oefeningen Lichamelijke oefeningen in groepsverband bestaande uit meerdere categorieën verlaagt de valfrequentie bij thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Freiburger, 2012; Gianoudis, 2014; Llife, 2014; Patil, 2015) |

|

Matig GRADE |

Individueel: Meerdere categorieën lichamelijke oefeningen Individuele lichamelijke oefeningen bestaande uit meerdere categorieën verlaagt de valfrequentie bij thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Gleeson, 2015; Llife, 2014; Suttanon, 2013) |

|

Matig GRADE |

Tai Chi (groepsverband) Tai Chi oefeningen in groepsverband verlaagt de valfrequentie bij thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012) |

Botbreuken

|

Matig GRADE |

Lichamelijke oefeningen verlagen het risico op een botbreuk bij thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Gianoudis, 2014; Gleeson, 2015; Kim, 2014; Patil, 2015) |

2. Lichamelijke oefeningen versus lichamelijke oefeningen

|

- GRADE |

Vanwege het lage aantal trials per vergelijking is het niet mogelijk om een conclusie te formuleren over het effect van lichamelijke oefeningen vergeleken met andere lichamelijke oefeningen op het aantal vallers, valfrequentie of botbreuken.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; day, 2015; Taylor, 2012; Yamada, 2013) |

3. Vitmine D supplementen versus geen vitamine D supplementen of calcium

Aantal vallers

|

Matig GRADE |

Vitamine D suppletie met of zonder calcium heeft geen effect op het aantal vallers vergeleken met controle, placebo of calcium bij thuiswonenden.

Bronnen (Subgroep – deelnemers met laag niveau) |

|

Matig GRADE |

Vitamine D suppletie met of zonder calcium verlaagt aantal vallers vergeleken met controle, placebo of calcium bij thuiswonenden met een laag vitamine D niveau.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012) |

Valfrequentie

|

Matig GRADE |

Vitamine D suppletie met of zonder calcium heeft geen effect op de valfrequentie vergeleken met controle, placebo of calcium bij thuiswonenden.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Uusi-Rasi, 2015) |

|

Matig GRADE |

Subgroep – deelnemers met laag vitamine D Vitamine D suppletie met of zonder calcium verlaagt de valfrequentie vergeleken met controle, placebo of calcium bij thuiswonenden met een laag vitamine D niveau.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Uusi-Rasi, 2015) |

Botbreuken

|

Hoog GRADE |

Vitamine D suppletie met of zonder calcium heeft geen effect op het risico op een botbreuk vergeleken met controle, placebo of calcium bij thuiswonenden.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012) |

4. Vloeistof of voedingstherapie versus controle

Geen conclusies

5. Omgeving interventies versus reguliere zorg

Aantal vallers

|

Hoog GRADE |

Persoon-omgeving interventies verlagen het aantal vallers onder thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Kamei, 2015) |

Valfrequentie

|

Matig GRADE |

De valfrequentie onder thuiswonenden wordt door omgeving interventies verlaagd vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Kamei, 2015) |

Botbreuken

|

Zeer laag GRADE |

Het is onduidelijk of een omgeving interventie het risico op botbreuken verlaagt vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012) |

6. Multifactoriële interventies versus controle

Aantal vallers

|

Matig GRADE |

Multifactoriële interventies hebben geen effect op het aantal vallers onder thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Lee, 2013; Fairhall, 2014; Moller, 2014; Palvanen, 2014) |

Valfrequentie

|

Laag GRADE |

De valfrequentie onder thuiswonenden is verlaagd bij multifactoriele interventies vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Perula, 2012; Lee, 2013; Fairhall, 2014; Palvanen, 2014) |

Botbreuken

|

Laag GRADE |

Het risico op een botbreuk is mogelijk verlaagd door multifactoriele interventies bij thuiswonenden vergeleken met controle.

Bronnen (Gillespie, 2012; Fairhall, 2014; Palvanen, 2014) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Beschrijving studies

Gillespie, 2012 heeft een systematische zoekactie gedaan naar de effecten van interventies om de incidentie van vallen in thuiswonende ouderen te verlagen. De zoekactie was in februari 2012 uitgevoerd. Uiteindelijk waren 159 trials met in totaal 79.193 deelnemers geïncludeerd. De meeste trials vergeleken een interventie voor valpreventie met geen interventie of met een interventie zonder verwacht effect op vallen. Oefeningen als een enkele interventie als ook multifactoriële programma’s waren de meest voorkomende onderzochte interventies. De volgende categorieën van interventie (met vergelijkende groep) ter preventie van vallen waren beschreven in het Cochrane review:

- beweeginterventie versus controle of andere lichamelijke oefeningen;

- vitamine D supplementen versus geen vitamine D supplementen of calcium;

- andere medicamenten versus controle;

- stoppen met medicatie versus controle;

- operatie versus controle;

- vloeistof of voedingstherapie versus controle;

- psychologische interventies versus controle;

- omgeving interventies versus reguliere zorg;

- kennisoverdracht interventies versus controle;

- meerdere interventies;

- multifactoriële interventies versus controle.

Beschrijving nieuwe studies

Uit de update van de Cochrane review werden 20 nieuwe trials met in totaal 7392 patiënten geïncludeerd. De geïncludeerde trials leverde additionele gegevens voor de volgende vergelijkingen:

- lichamelijke oefeningen versus controle of andere lichamelijke oefeningen;

- vitamine D supplementen versus geen vitamine D supplementen of calcium;

- vloeistof of voedingstherapie versus controle;

- omgeving interventies versus reguliere zorg;

- multifactoriële interventies versus controle.

Een overzicht van deze trials wordt in de onderstaande tabel gegeven.

|

|

|

|

Uitkomstmaten |

||

|

Auteur, jaar |

Interventie; Controle |

N |

Aantal vallers |

Val frequentie |

Botbreuken |

|

Day, 2015 |

Tai chi |

250 |

ü |

ü |

- |

|

|

Flexibiliteit en strekprogramma |

253 |

|

|

|

|

Gleeson, 2015 |

Alexander Technique lesson |

60 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Reguliere zorg door een geleidehond |

60 |

|

|

|

|

Patil, 2015 |

Lichamelijke oefeningen |

205 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Huidige fysieke activiteit |

204 |

|

|

|

|

Gianoudis, 2014 |

Lichamelijke oefeningen, osteoporose kennisoverdracht en gedragsverandering |

81 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Reguliere zorg |

81 |

|

|

|

|

Kim, 2014 |

Lichamelijke oefeningen |

52 |

ü |

- |

ü |

|

|

Kennisoverdracht |

53 |

|

|

|

|

Lliffe, 2014 |

1 Home-based Otago Exercise Programma (OEP) 2 Community-based group exercise programma |

1: 411 2: 387 |

- |

ü |

- |

|

|

Reguliere zorg |

458 |

|

|

|

|

Suttanon, 2013 |

Lichamelijke oefeningen – balans en spierversterkende oefeningen |

19 |

ü |

ü |

-

|

|

|

Kennisoverdracht |

21 |

|

|

|

|

Yamada, 2013 |

Stapprogramma en lichamelijke oefeningen |

132 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Wandelprogramma en lichamelijke oefeningen |

132 |

|

|

|

|

Clemson, 2012 |

|

1: 107 2: 105 |

ü |

ü |

-

|

|

|

Lichte lichamelijke oefeningen, gericht op flexibiliteit |

105 |

|

|

|

|

Taylor, 2012 |

|

1: 233 2: 220 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Lichte lichamelijke oefeningen |

231 |

|

|

|

|

Suominen, 2015 |

Afgestemd voeding begeleiding met huisbezoeken |

50 |

- |

ü |

- |

|

|

Geschreven informatie over voedsel |

44 |

|

|

|

|

Uusi-Rasi, 2015 |

Vitamine D3 (800 IU per dag) |

102 |

- |

ü |

- |

|

|

Placebo |

102 |

|

|

|

|

Kamei, 2015 |

Kennisoverdracht en programma gericht op gevaren in huis. |

67 |

ü |

ü |

- |

|

|

Controle – kennisoverdracht veroudering en gezondheid |

63 |

|

|

|

|

Tchalla, 2013 |

Huis gebaseerd technologie met assistentie service tezamen met een valrisico verlagend programma |

49 |

ü |

ü |

-

|

|

|

Een valrisico verlagend programma |

47 |

|

|

|

|

Fairhall, 2014 |

Multifactorieel – individueel afgestemd lichamelijke oefeningen bovenop reguliere zorg |

120 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Reguliere zorg |

121 |

|

|

|

|

Moller, 2014 |

Multifactorieel – casemanagement, algemene informatie over onder andere lichamelijke oefeningen en voeding, individueel afgestemde informatie en veiligheid |

80 |

ü |

- |

- |

|

|

Controle |

73 |

|

|

|

|

Palvanen, 2014 |

Multifactorieel – individueel afgestemd valreductieprogramma met lichamelijke oefeningen, medicatie beoordeling, voeding en beoordeling van gevaren in huis |

661 |

ü |

ü |

ü |

|

|

Controle bestaande uit een algemene brochure over het voorkomen van letsel |

653 |

|

|

|

|

Lee, 2013 |

Multifactorieel – lichamelijke oefeningen, kennisoverdracht gezondheid en beoordeling van gevaren in huis |

313 |

ü |

ü |

-

|

|

|

Controle – brochures, medicatie beoordeling |

303 |

|

|

|

|

Perula, 2012 |

Multifactorieel – individueel afgestemd advies, informatie brochure, lichamelijke oefeningen en huisbezoeken |

133 |

- |

ü |

- |

|

|

Controle – reguliere zorg met een brochure |

271 |

|

|

|

Vanwege de grootte van de Cochrane review zullen nu alleen de vergelijkingen worden beschreven waarvoor additionele data beschikbaar is. Voor de overige vergelijkingen wordt naar de Cochrane review verwezen.

Interventies ter preventie van vallen

1. Lichamelijke oefeningen versus controle

De Cochrane review van Gillespie (2012) kon met 11 trials worden geüpdatet. Vanwege de hoeveelheid aan studies is ervoor gekozen om geen korte beschrijving te geven, maar wordt verwezen naar de tabel met geïncludeerde studies.

Resultaten

I. Vallen

I.I Het aantal vallers

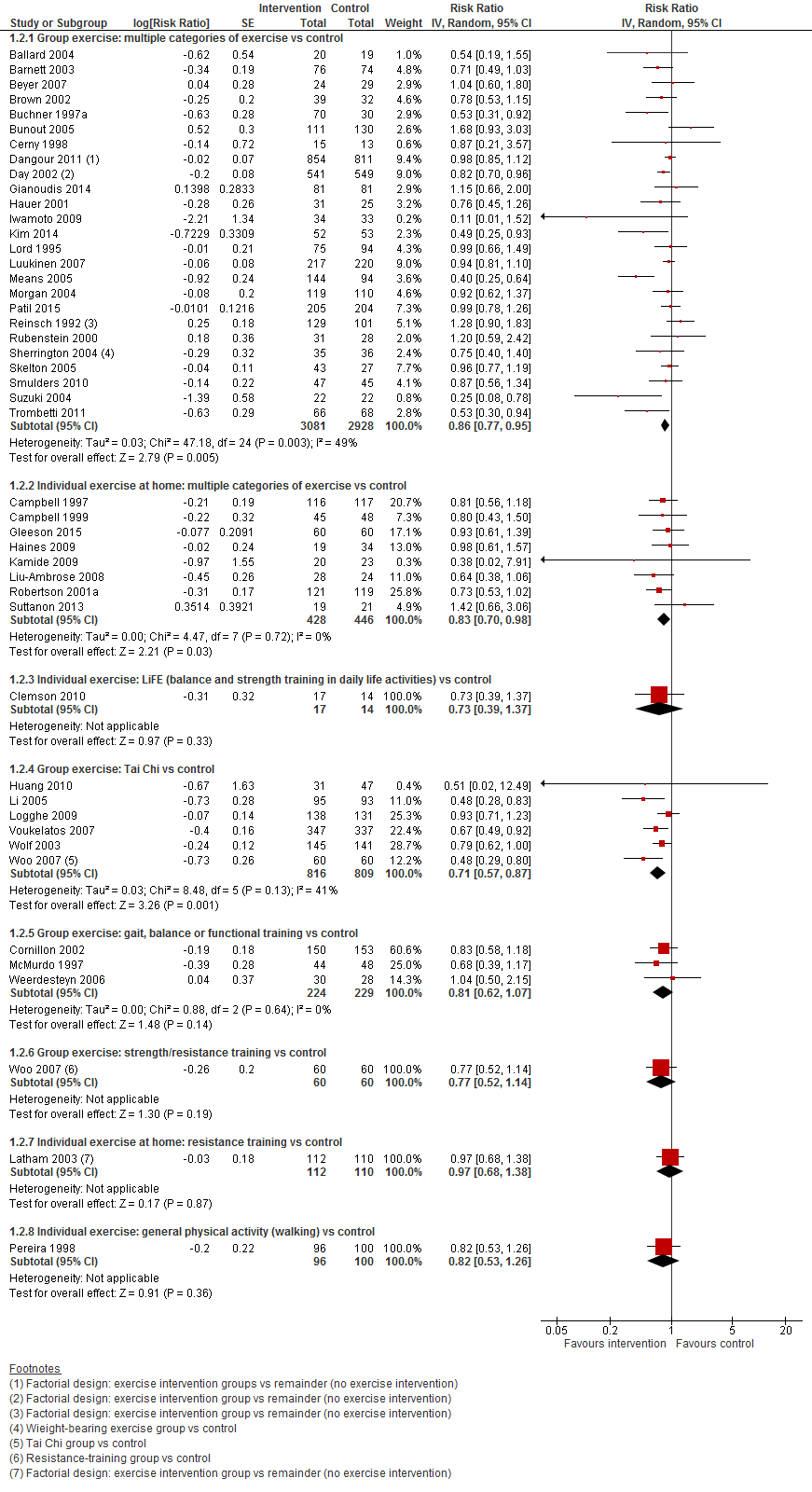

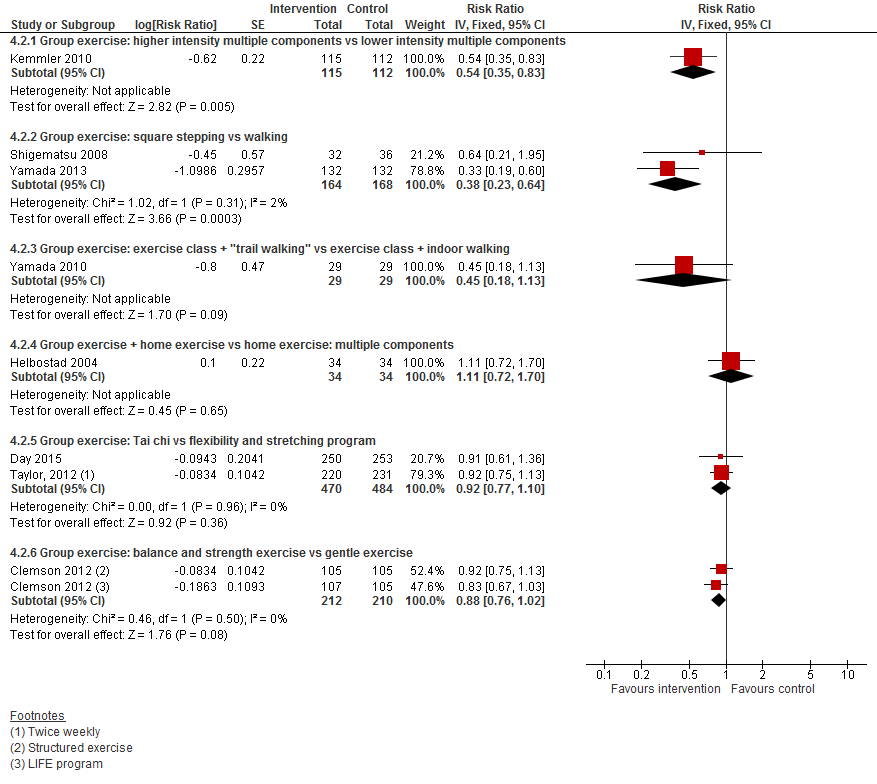

In figuur 1 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst het aantal vallers weergegeven. Hierbij zijn de resultaten per type interventie apart weergegeven. Zonder te focussen op een type van interventie is te zien dat alle interventies met lichamelijke oefeningen in ieder geval het risico om te vallen niet vergroten vergeleken met controle.

Bij een lichamelijke oefening bestaande uit meerdere categorieën in groepsverband is het risico om te vallen verlaagd. Het aantal thuiswonenden die dit type interventie kregen en vielen was met 14% verlaagd vergeleken met de controlegroep (RR 0,86 95%BI: 0,77 tot 0,95). Ook bij oefeningen die thuis gegeven waren, was het aantal vallers verlaagd (RR 0,83 95%BI: 0,70 tot 0,98). Het aantal vallers was ook verlaagd bij Tai Chi oefeningen gegeven in groepsverband. Het aantal vallers nam met 29% af vergeleken met controle (RR 0,71 95%BI: 0,57 tot 0,87).

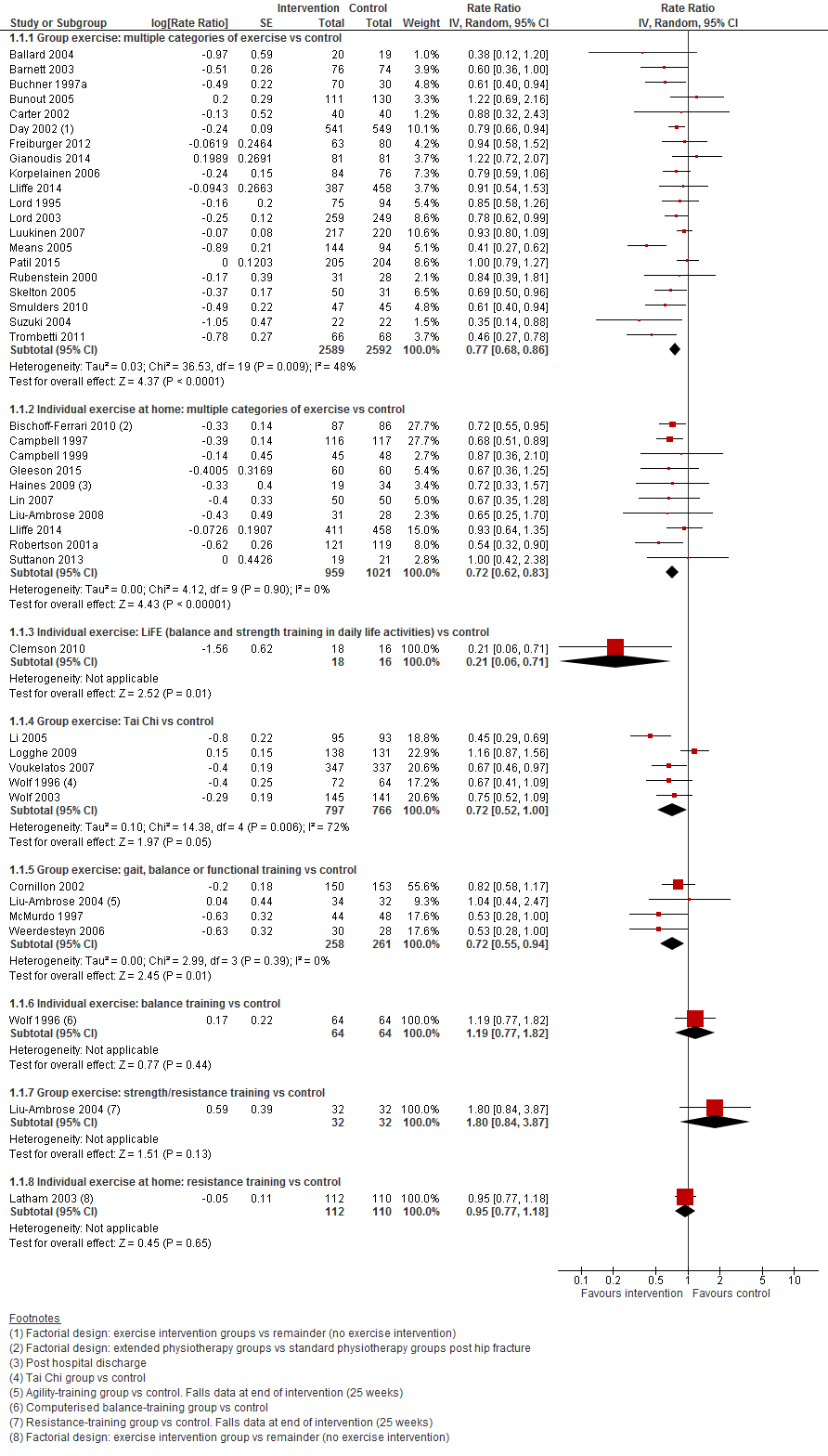

I.II Valfrequentie

In figuur 2 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst valfrequentie weergegeven. Hierbij zijn de resultaten per type interventie apart weergegeven. Over het algemeen verlagen de interventie de valfrequentie. Vergelijkbare resultaten als het aantal vallers werd gevonden. Bij een lichamelijke oefening bestaande uit meerdere categorieën in groepsverband was de valfrequentie met 33% afgenomen (RR 0,77 95%BI: 0,68 tot 0,86). Ook individueel gegeven lichamelijke oefeningen verlaagde de valfrequentie (RR 0,72 95%BI: 0,62 tot 0,83). Een vergelijkbaar effect werd waargenomen bij Tai Chi oefeningen al met een breder betrouwbaarheidsinterval (RR 0,72 95%BI: 0,52 tot 1,00).

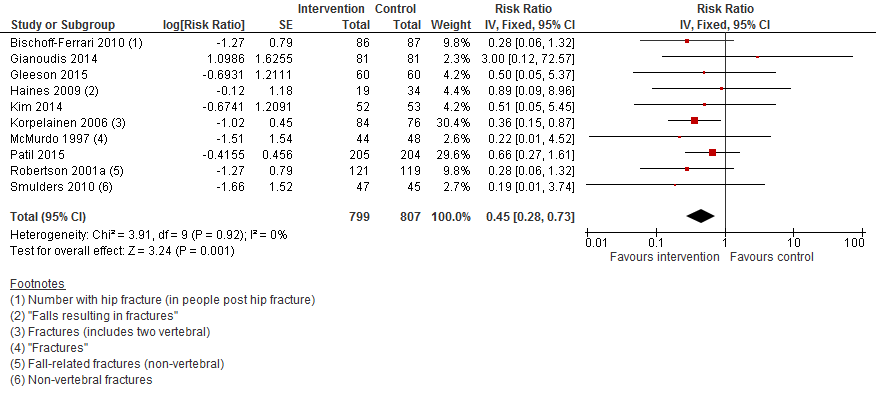

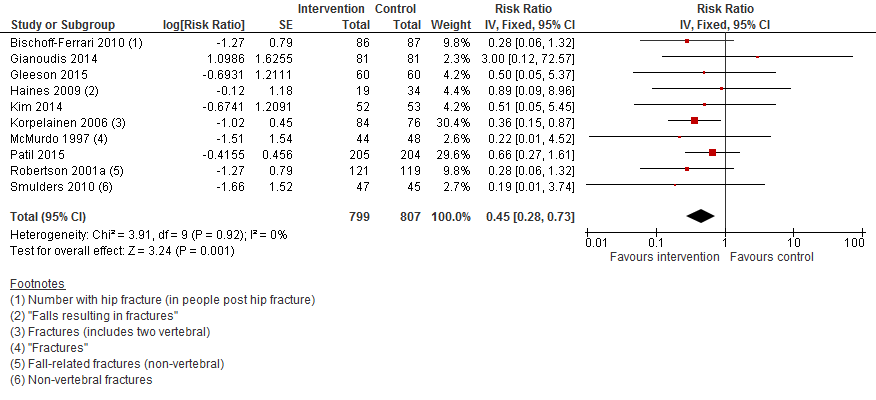

I.III Botbreuken

In figuur 3 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst botbreuken weergegeven. Vanwege het lage aantal trials heeft de Cochrane review deze niet per type interventie gestratificeerd. Ongeacht welke lichamelijke oefeningen worden gevonden en of dit individueel of in groepsverband werd gegeven, was het risico op een botbreuk met 55% verlaagd vergeleken met controle (RR 0,45 95%BI: 0,28 tot 0,73).

Figuur 1 Meta-analyse: lichamelijke oefeningen en uitkomst het aantal vallers

Figuur 2 Meta-analyse: lichamelijke oefeningen en uitkomst valfrequentie

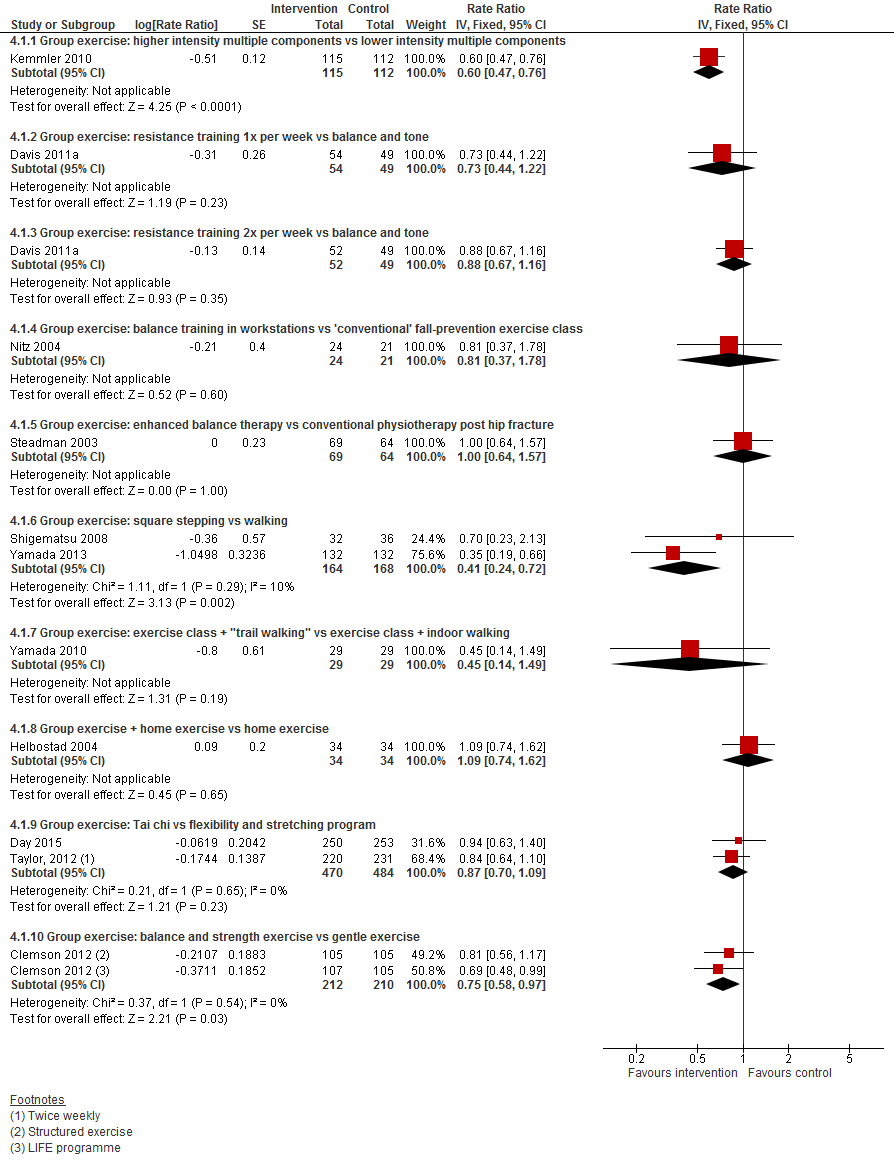

Figuur 3 Meta-analyse: lichamelijke oefeningen en uitkomst botbreuken

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

Aantal vallers: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat het aantal vallers is met twee niveaus verlaagd gezien beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (gebrek aan blindering van toewijzers en deelnemers) en tegenstrijdige resultaten (inconsistentie) of het geringe aantal patiënten (imprecisie).

Valfrequentie: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat valfrequentie is met één niveau verlaagd gezien beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (gebrek aan blindering van toewijzers en deelnemers). Voor interventie Tai Chi is een extra niveau verlaagd vanwege imprecisie (breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval).

Botbreuken: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat botbreuken is met één niveau verlaagd gezien beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (gebrek aan blindering van toewijzers en deelnemers).

2. Lichamelijke oefeningen versus lichamelijke oefeningen

De Cochrane review van Gillespie, 2012 kon met 11 trials worden geüpdatet. Vanwege de hoeveelheid aan studies is ervoor gekozen om geen korte beschrijving te geven, maar wordt verwezen naar de tabel met geïncludeerde studies.

Resultaten

I. Vallen

I.I Het aantal vallers

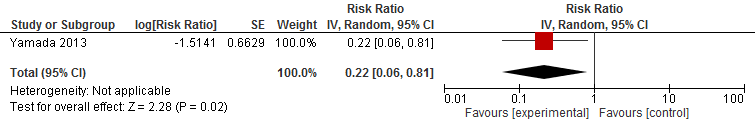

In figuur 4 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst het aantal vallers weergegeven. Per type interventie was één of twee trials beschikbaar, waardoor het niet mogelijk was een conclusie te trekken.

I.II Valfrequentie

In figuur 5 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst valfrequentie weergegeven. Ook bij deze uitkomst waren er per type één of twee trials beschikbaar en daardoor was het moeilijk om een conclusie te formuleren.

I.III Botbreuken

In figuur 6 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst botbreuken weergegeven. Echter, één trial had het effect van lichamelijke oefeningen vergeleken met andere lichamelijk oefeningen op botbreuken gerapporteerd.

Figuur 4 Lichamelijke oefeningen en uitkomst het aantal vallers

Figuur 5 Lichamelijke oefeningen en uitkomst valfrequentie

Figuur 6 Lichamelijke oefeningen en uitkomst botbreuken

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

Vanwege het lage aantal trials per vergelijking is het niet mogelijk om de bewijskracht te graderen of een conclusie te formuleren.

3. Vitmine D supplementen versus geen vitamine D supplementen of calcium

De Cochrane review van Gillespie (2011) kon met een additionele trial worden geüpdatet. In het kort, Uusi-Rasi (2015) vergeleek suppletie met vitamine D3 (800 IU per dag voor 24 maanden) met placebo bij vrouwen in de leeftijd tussen 70 en 80 jaar.

Resultaten

I. Vallen

I.I Het aantal vallers

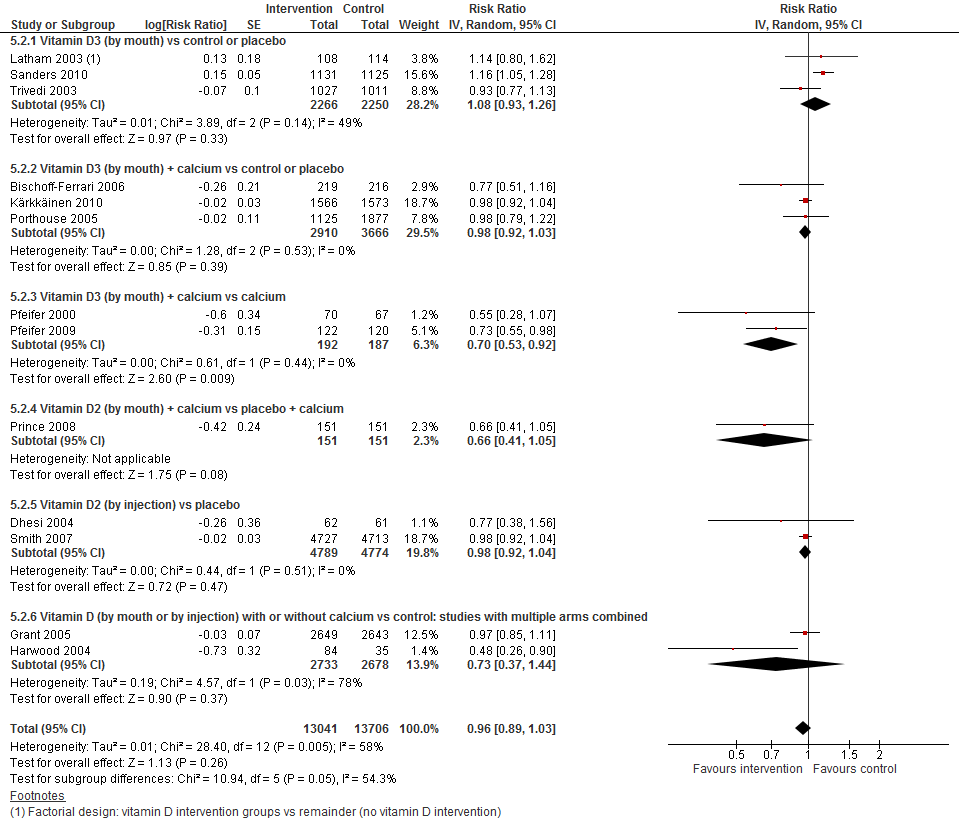

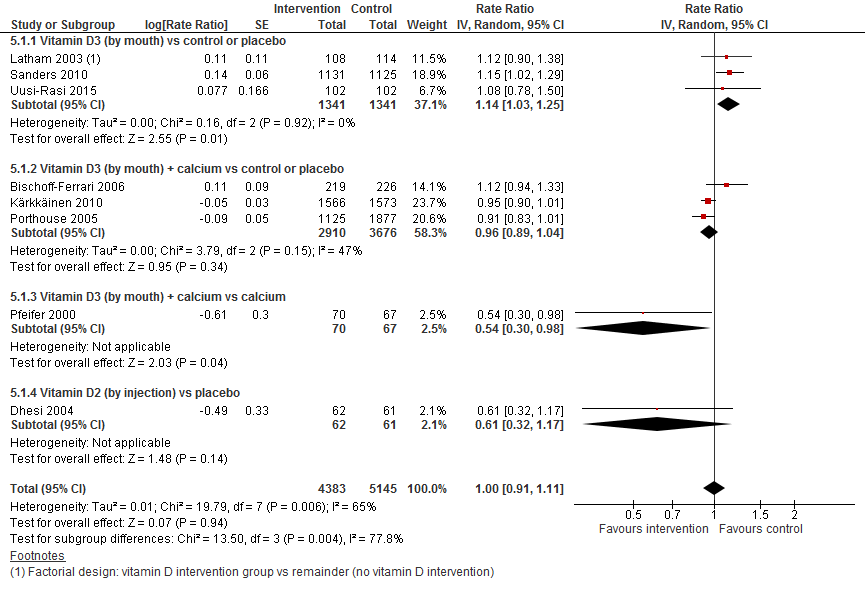

In figuur 7 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst het aantal vallers weergegeven. Per type interventie en vergelijking waren tussen de een en drie trials beschikbaar. Ongeacht de interventie en controlegroep heeft vitamine D suppletie geen effect op het aantal vallers (RR 0,96 95%BI: 0,89 tot 1,03). De meta-analyse lijkt te suggereren dat bij bepaalde interventies ook een potentieel verlagend effect hebben op het aantal vallers. Vanwege het lage aantal trials per vergelijking is het echter niet mogelijk om een conclusie te formuleren bij welke interventies thuiswonenden baat zouden hebben.

Figuur 7 Vitamine D suppletie en uitkomst aantal vallers

I.II Valfrequentie

In figuur 8 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst valfrequentie weergegeven. Per type interventie en vergelijking waren tussen de een en drie trials beschikbaar. Ongeacht de interventie en controlegroep heeft vitamine D suppletie geen effect op de valfrequentie (RR 1,00 95%BI: 0,91 tot 1,11). Dit overal effect wordt bevestigd door de resultaten van de subgroepen vitamine D suppletie versus controle of vitamine D tezamen met calcium versus controle.

Figuur 8 Vitamine D suppletie en uitkomst valfrequentie

I.III Botbreuken

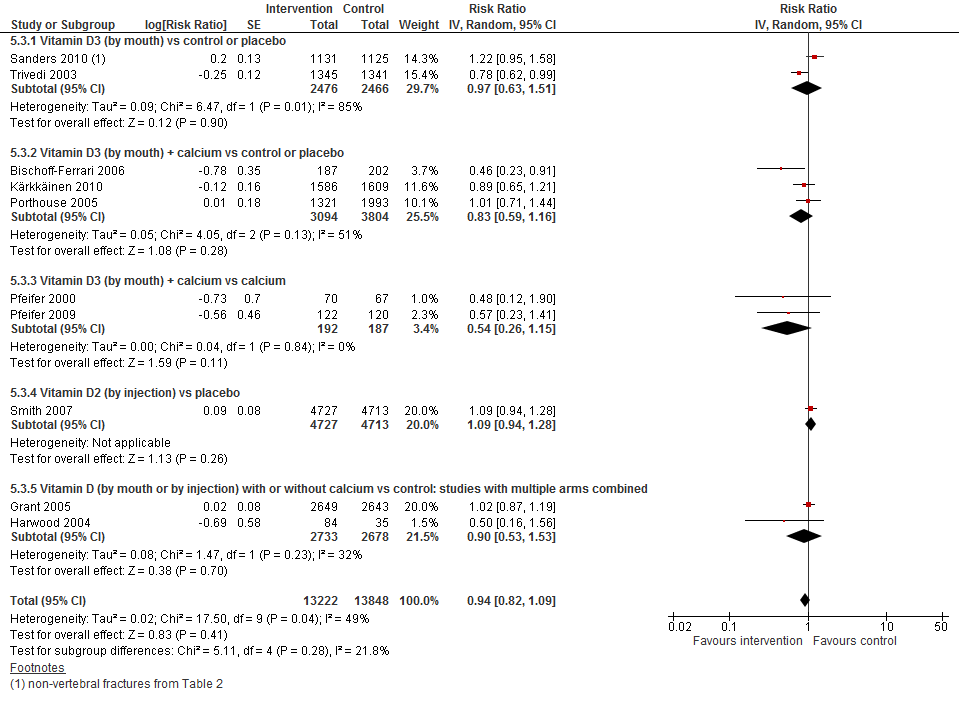

In figuur 9 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst botbreuken weergegeven. Vitamine D suppletie verlaagt niet het risico op een botbreuk bij thuiswonenden (RR 0,94 95%BI: 0,82 tot 1,09). Ook de gegevens uit de verschillende interventies laten hetzelfde effect zien. Alleen vitamine D tezamen met calcium vergeleken met alleen calcium suggereert een potentieel verlaagd effect.

Figuur 9 Vitamine D suppletie en uitkomst botbreuken

Subgroep analyse

Gillespie (2011) voerde een subgroep analyse uit met trials die alleen deelnemers met een laag vitamine D niveau includeerden. Het aantal vallers en de valfrequentie was lager bij gebruik van vitamine D suppletie door deelnemers met laag vitamine D versus controle (RR 0,70 95%BI: 0,56 tot 0,87 en RR 0,57 95%BI: 0,37 tot 0,89, respectievelijk). Voor de meta-analyses verwijzen we naar de Cochrane review van Gillespie (2011).

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

Aantal vallers: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat het aantal vallers is met een niveau verlaagd gezien tegenstrijdige resultaten (inconsistentie). Subgroep met laag vitamine D: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat het aantal vallers is met twee niveaus verlaagd gezien imprecisie (lage aantal deelnemers).

Valfrequentie: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat valfrequentie is met één niveau verlaagd gezien beperkingen in de onderzoeksopzet (gebrek aan blindering en follow-up). Subgroep met laag vitamine D: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat valfrequentie is met een niveau verlaagd gezien imprecisie (lage aantal deelnemers).

4. Vloeistof of voedingstherapie versus controle

De update van de Cochrane review leverde een trial (Suominen, 2015) op die individueel afgestemde voedingsbegeleiding vergeleek met een brochure over voeding. Suominen (2015) rapporteerde alleen het effect op de valfrequentie. Dit resultaat werd gecorrigeerd voor leeftijd, geslacht en MMSE. Tevens werd het effect berekend als controle versus interventie in plaats van de gebruikelijk vergelijking interventie versus controle. Om deze reden wordt dit resultaat niet meegenomen. Met andere woorden, gegevens van Suominen (2015) konden niet worden toegevoegd aan de beschikbare data uit de Cochrane review. Voor de resultaten op het aantal vallers wordt naar de review verwezen.

5. Omgeving interventies versus reguliere zorg

Twee additionele trials (Kamei, 2015; Tchalla, 2013) konden worden toegevoegd aan de reeds beschikbare data uit de review van Gillespie (2011). Kamei (2015) evalueerde een uitgebreid programma gericht op gevaren in huis, waarbij de interventie uitleg en oefeningen kregen gericht op gevaren en de controlegroep kregen informatie over ouder worden en gezondheid. In de trial van Tchalla (2013) deden alle deelnemers mee aan een programma om het vallen te verminderen en kreeg de interventiegroep additioneel een nachtlampje om vallen thuis te voorkomen. Tchalla (2013) rapporteerde geadjusteerde odds ratios en cumulatieve incidentie waardoor het niet mogelijk was om de data te poolen met de reeds beschikbare meta-analyse van Gillespie (2011).

Resultaten

I. Vallen

I.I Het aantal vallers

In figuur 10 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst het aantal vallers weergegeven. Een omgevingsgerichte interventies verlaagt het aantal vallers met 13% (RR 0,87 95%BI: 0,80 tot 0,95).

Figuur 10 Omgeving interventies en uitkomst het aantal vallers

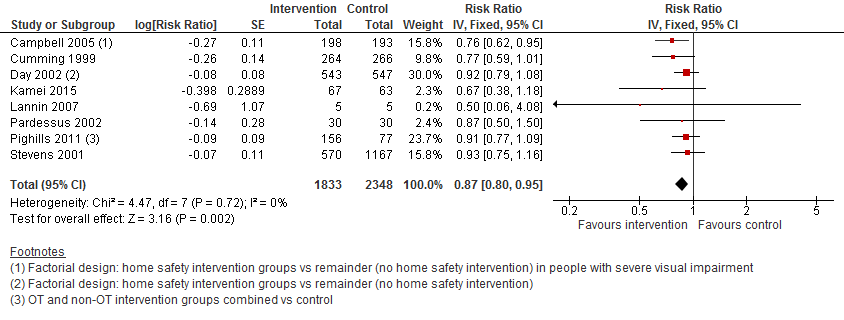

I.II Valfrequentie

In figuur 11 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst valfrequentie weergegeven. Een omgeving interventie verlaagt de valfrequentie met 20% vergeleken met controle (RR 0,80 95%BI: 0,67 tot 0,95).

Figuur 11 Omgeving interventies en uitkomst valfrequentie

Uit het onderzoek van Pighills (2011) blijkt dat een persoon-omgevingsinterventie uitgevoerd door ergotherapeuten effectiever is dan dezelfde interventie uitgevoerd door hiertoe getrainde thuiszorgmedewerkers. Het gaat hier om interventies waarin zowel de omgeving aangepast wordt als geoefend wordt in die omgeving, dit zijn niet enkel omgevingsinterventies.

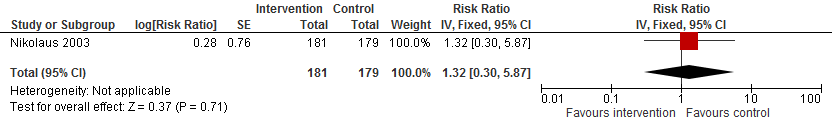

I.III Botbreuken

In figuur 12 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst botbreuken weergegeven. Alleen Nikolaus (2013) rapporteert het effect van een omgeving interventie op het risico op een botbreuk. Het risico is potentieel met 32% verhoogd (RR 1,32 95%BI: 0,30 tot 5,87).

Figuur 12 Omgeving interventies en uitkomst botbreuken

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

Valfrequentie: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat valfrequentie is met één niveau verlaagd gezien tegenstrijdige resultaten (inconsistentie).

Botbreuk: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat botbreuken is met drie niveaus verlaagd gezien beperkingen in studieopzet (risk of bias; outcome assessors waren niet geblindeerd) en imprecisie (laag aantal events en breed betrouwbaarheidsinterval).

6. Multifactoriële interventies versus controle

De zoekactie leverde vijf additionele trials op die multifactoriële interventies onderzocht. Vanwege het verschil in interventies wordt naar het overzicht met geïncludeerde trials verwezen voor een beschrijving van de interventie.

Resultaten

I. Vallen

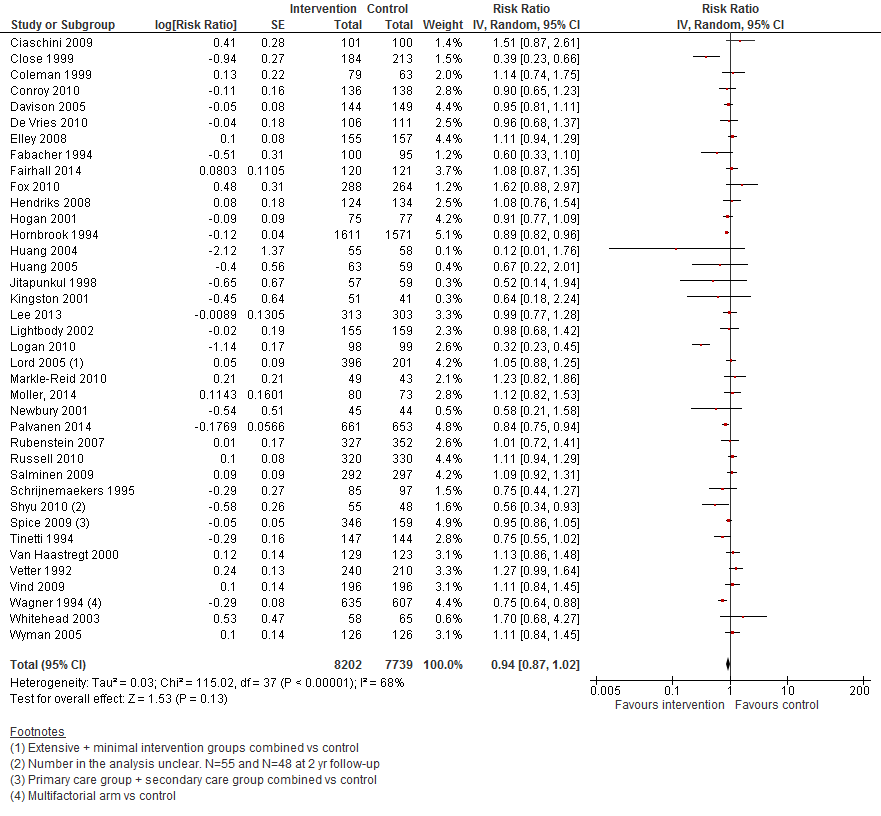

I.I Het aantal vallers

In figuur 13 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst het aantal vallers weergegeven. Multifactoriële interventies hebben geen effect op het aantal vallers vergeleken met controle (RR 0,94 95%BI: 0,87 tot 1,02).

Figuur 13 Multifactoriële interventies en uitkomst het aantal vallers

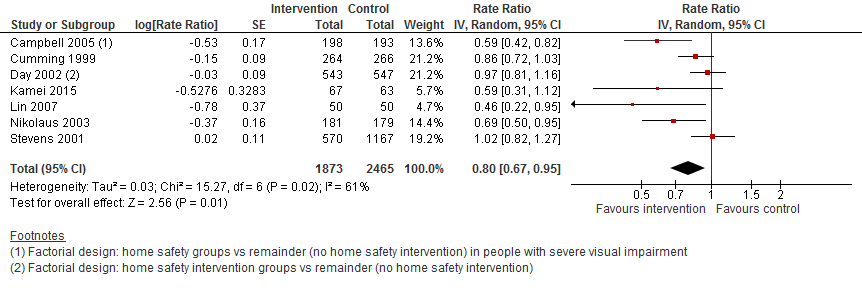

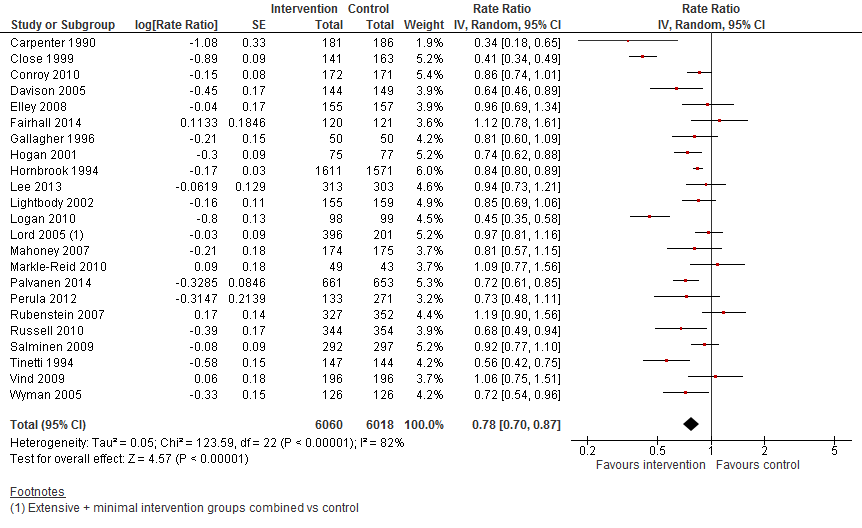

I.II Valfrequentie

In figuur 14 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst valfrequentie weergegeven. Multifactoriële interventies verlagen de valfrequentie onder thuiswonenden met 22% (RR 0,78 95%BI: 0,70 tot 0,87).

Figuur 14 Multifactoriele interventies en uitkomst valfrequentie

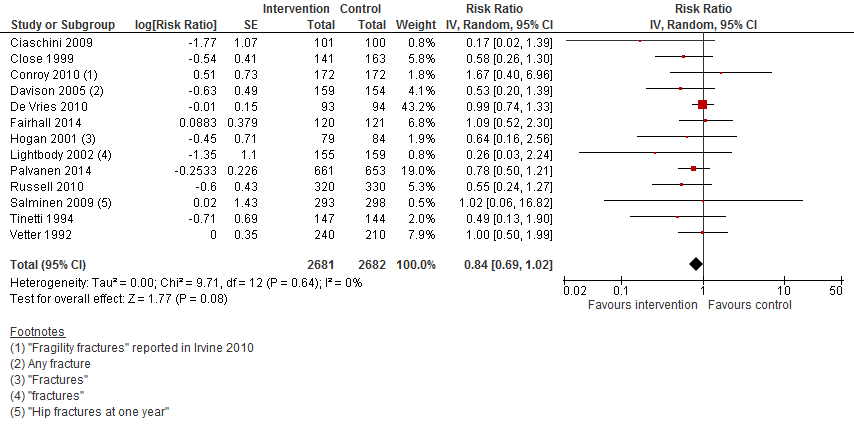

I.III Botbreuken

In figuur 15 staan de resultaten op de uitkomst botbreuken weergegeven. Multifactoriële interventies verlagen het risico op een botbreuk met 16% (RR 0,84 95%BI: 0,69 tot 1,02).

Figuur 15 Multifactoriële interventies en uitkomst botbreuken

Bewijskracht van de literatuur

Aantal vallers: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat aantal vallers is met één niveau verlaagd gezien beperkingen in studieopzet (risk of bias).

Valfrequentie: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat valfrequentie is met twee niveaus verlaagd gezien beperkingen in studieopzet (risk of bias) en tegenstrijdige resultaten (inconsistentie).

Botbreuk: De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaat botbreuken is met twee niveaus verlaagd gezien beperkingen in studieopzet (risk of bias) en tegenstrijdige resultaten (inconsistentie).

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende wetenschappelijke vraagstelling(en):

Wat is de effectiviteit en veiligheid van valrisico verlagende interventie vergeleken met geen interventie bij thuiswonende ouder patiënten met een valrisico?

P thuiswonende oudere patiënten met valrisico;

I interventies gericht op het verlagen van het valrisico;

C geen / andere interventies die geen effect hebben op vallen;

O valrisico (aantal vallers en valfrequentie) / botbreuken.

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte vallen een voor de besluitvorming kritieke uitkomstmaat; en botbreuken een voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaat.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities.

Per uitkomstmaat: de werkgroep definieerde het verlagen van het aantal valincidenten evenals het voorkomen van valincidenten als een klinisch relevant verschil.

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

Voor de uitwerking van deze vraag wordt een bestaande Cochrane review geüpdatet. Gillespie, 2012 ondernamen een systematische literatuur zoekactie naar interventies om de incidentie van vallen in thuiswonende ouderen te verlagen. De Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group Specialised register, CENTRAL, Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL en online trial registers waren met relevante zoektermen doorzocht. Dezelfde zoekstrategie is gebruikt om de Cochrane review up te daten.

De zoekverantwoording is weergegeven onder het tabblad Verantwoording. De literatuurzoekactie leverde 2.923 treffers op. Studies werden geselecteerd op grond van de volgende selectiecriteria: gerandomiseerde trials met interventies ter preventie van vallen in thuiswonende ouderen. Op basis van titel en abstract werden in eerste instantie 211 studies voorgeselecteerd. Na raadpleging van de volledige tekst, werden vervolgens 191 studies geëxcludeerd (zie exclusietabel), en 20 studies definitief geselecteerd.

Resultaten

Twintig onderzoeken zijn opgenomen in de literatuuranalyse. De belangrijkste studiekarakteristieken en resultaten zijn opgenomen in de evidence-tabellen. De evidence-tabellen en beoordeling van individuele studiekwaliteit zijn opgenomen onder het tabblad Onderbouwing.

Referenties

- Clemson L, Fiatarone Singh MA, Bundy A, et al. Integration of balance and strength training into daily life activity to reduce rate of falls in older people (the LiFE study): randomised parallel trial. BMJ. 2012;345:e4547.

- Day L, Hill KD, Stathakis VZ, et al. Impact of tai-chi on falls among preclinically disabled older people. A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2015;16(5):420-6.

- Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Lord SR, et al. Effect of a multifactorial, interdisciplinary intervention on risk factors for falls and fall rate in frail older people: a randomised controlled trial. Age & Ageing. 2014;43(5):616-22.

- Gianoudis J, Bailey CA, Ebeling PR, et al. Effects of a targeted multimodal exercise program incorporating high-speed power training on falls and fracture risk factors in older adults: a community-based randomized controlled trial. Journal of Bone & Mineral Research. 2014;29(1):182-91.

- Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. Review. PubMed PMID: 22972103.

- Gleeson M, Sherrington C, Lo S, et al. Can the Alexander Technique improve balance and mobility in older adults with visual impairments? A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2015;29(3):244-60.

- Iliffe S, Kendrick D, Morris R, et al. Multicentre cluster randomised trial comparing a community group exercise programme and home-based exercise with usual care for people aged 65 years and over in primary care. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England). 2014;18(49):vii-xxvii, 1-105.

- Kamei T, Kajii F, Yamamoto Y, et al. Effectiveness of a home hazard modification program for reducing falls in urban community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Japan Journal of Nursing Science: JJNS. 2015;12(3):184-97.

- Karlsson, MK, Vonschewelov T, Karlsson, C, et al. Prevention of falls in the elderly: A review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2013;41:442-54.

- Kim H, Yoshida H, Suzuki T. Falls and fractures in participants and excluded non-participants of a fall prevention exercise program for elderly women with a history of falls: 1-year follow-up study. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2014;14(2):285-92.

- Lee HC, Chang KC, Tsauo JY, et al. Effects of a multifactorial fall prevention program on fall incidence and physical function in community-dwelling older adults with risk of falls. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2013;94(4):606-15, 15.e1.

- Moller UO, Kristensson J, Midlov P, et al. Effects of a one-year home-based case management intervention on falls in older people: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Aging & Physical Activity. 2014;22(4):457-64.

- Palvanen M, Kannus P, Piirtola M, et al. Effectiveness of the Chaos Falls Clinic in preventing falls and injuries of home-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. Injury. 2014;45(1):265-71.

- Patil R, Uusi-Rasi K, Tokola K, et al. Effects of a Multimodal Exercise Program on Physical Function, Falls, and Injuries in Older Women: A 2-Year Community-Based, Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015;63(7):1306-13.

- Perula LA, Varas-Fabra F, Rodriguez V, et al. Effectiveness of a multifactorial intervention program to reduce falls incidence among community-living older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2012;93(10):1677-84.

- Pighills AC, Torgerson DJ, Sheldon TA, et al. Environmental assessment and modification to prevent falls in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):26-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03221.x. Erratum in: J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(4):776. PubMed PMID: 21226674.

- Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, et al. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2234-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02014.x. Review. PubMed PMID: 19093923.

- Suominen MH, Puranen TM, Jyväkorpi SK, et al. Nutritional guidance improves nutrient intake and quality of life, and may prevent falls in aged persons with Alzheimer disease living with a spouse (NuAD Trial). Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging. 2015.

- Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, et al. Feasibility, safety and preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of a home-based exercise programme for older people with Alzheimer's disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2013;27(5):427-38.

- Taylor D, Hale L, Schluter P, et al. Effectiveness of tai chi as a community-based falls prevention intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60(5):841-8.

- Tchalla AE, Lachal F, Cardinaud N, et al. Preventing and managing indoor falls with home-based technologies in mild and moderate Alzheimer's disease patients: pilot study in a community dwelling. Dementia & Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2013;36(3-4):251-61.

- Uusi-Rasi K, Patil R, Karinkanta S, et al. Exercise and vitamin D in fall prevention among older women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2015;175(5):703-11.

- van Dijk SC, Sohl E, Oudshoorn C, et al. Non-linear associations between serum 25-OH vitamin D and indices of arterial stiffness and arteriosclerosis in an older population. Age Ageing. 2015;44(1):136-42. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu095. PubMed PMID: 25038832.

- Yamada M, Higuchi T, Nishiguchi S, et al. Multitarget stepping program in combination with a standardized multicomponent exercise program can prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(10):1669-75.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3 |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Exercises |

|||||||

|

Day, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Disabled community-dwelling people

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 250 Control:253

Important prognostic factors2: Described for analysed population

Age category, n (%) I: 70-74 years: 69 (34) 75-79 years: 62 (30) 80-84 years: 50 (25) ≥85 years: 23 (11) C: 70-74 years: 64 (31) 75-79 years: 64 (31) 80-84 years: 56 (27) ≥85 years: 21 (10)

Sex: I: 30% M C: 30% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Modified Sun style tai-chi and covered agility, mobility, balance, strength, breathing, and relaxation

Classes of 12-16 participants were held twice weekly for 60 minutes per class, for up to 24 weeks. |

Flexibility and stretching program, conducted primarily in the seated position

Classes of 12-16 participants were held twice weekly for 60 minutes per class, for up to 24 weeks. |

Length of follow-up: 24 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 46 (18%) Reasons: refused fall calendars

Control: N = 48 (19%) Reasons: refused fall calendars

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 46 (18%) Reasons: refused fall calendars

Control: N = 48 (19%) Reasons: refused fall calendars |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 100 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 38 (out of 204) C: 42 (out of 205) RR 0.91 (95%CI 0.61-1.35)

Rate of falls, rate ratio I: 56.7 (46.7-66.7) C: 60.6 (50.8-70.4) RR 0.94 (95%CI 0.63-1.38)

2. Fractures Not reported |

Not only community dwellers included, but also residents from retirement villages.

Follow-up lasted till 48 weeks; however, as not all participants could participate till 48 weeks due to budget limitations, only data from 24 weeks was considered. |

|

Gleeson, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Participants’ homes

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 60 Control: 60 Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 74 (11) C: 74 (11)

Sex: I: 28% M C: 30% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Alexander Technique lesson for 12 weeks in addition to usual care.

Lessons were typically 30 minutes in length. A lesson protocol was developed using everyday activities such as movements between sitting and standing, getting to and from the floor, and walking, climbing stairs and carrying everyday articles. |

Usual care provided by Guide Dog (see comment) |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 5 (7%) Reasons: 1 refusal, 4 withdrawals

Control: N = 4 (7%) Reasons: 2 deaths and 2 withdrawals

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 5 (7%) Reasons: 1 refusal, 4 withdrawals

Control: N = 4 (7%) Reasons: 2 deaths and 2 withdrawals |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 25 (42) C: 27 (45) RR 0.93 (95%CI 0.61-1.39)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I1: 1.01 C: 1.49 RR 0.67 (95%CI 0.36-1.26)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 1 (2) C: 2 (2) |

“Participants were recruited from the client database of a community organisation providing support for people with visual impairments in Sydney, Australia (Guide Dogs).”

Falls were collected through calendars over 12 months. Authors stated that the study was not powered to detect an effect on fall rates. |

|

Patil, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Finland

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 205 Control: 204

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 74 (3) C: 74 (3)

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Exercise – Exercises classes twice a week for 12 months and once a week for the subsequent 12 months and home exercises |

Control – Current physical activity |

Length of follow-up: 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 18 (9%) Reasons: 5 lost interest; 13 due to health reasons

Control: N = 21 (10%) Reasons; 6 lost interest; 10 due to health reasons; 4 died; 1 spouse unwell

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 18 (9%) Reasons: 5 lost interest; 13 due to health reasons

Control: N = 21 (10%) Reasons; 6 lost interest; 10 due to health reasons; 4 died; 1 spouse unwell |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 100 person years

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 140 (68) C: 141 (69) RR 0.99 (95%CI 0.78-1.25)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I1: 233.8 C: 250.3 RR 1.00 (95%CI 0.79-1.26)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 8 (4) C: 12 (6) RR 0.66 (95%CI 0.27-1.61) |

Data on falls was collected through monthly fall diaries. |

|

Gianoudis, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 81 Control: 81

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 67 (7) C: 67 (6)

Sex: I: 26% M C: 27% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Osteo-cise: Strong Bones for Life multimodal exercise, osteoporosis education/awareness and behavioural change program |

Standard care self-management control group |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 5 (6%) Reasons: 1 death, 1 illness, 2 no time, 1 overseas

Control: N = 7 (9%) Reasons: 1 death; 1 illness, 5 lack of interest/other

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 5 (6%) Reasons: 1 death, 1 illness, 2 no time, 1 overseas

Control: N = 7 (9%) Reasons: 1 death; 1 illness, 5 lack of interest/other

|

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 29 (36) C: 25 (31) RR 1.15 (95%CI 0.66-1.99)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I: 0.57 C: 0.42 RR 1.22 (95%CI 0.72-2.04)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 1 (1) C: 0 (0) |

All participants were provided with and advised to take one vitamin D supplement and two calcium supplements each day throughout the study.

Data on falls were collected via monthly falls calendar. |

|

Kim, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Japan

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 52 Control: 53

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 77 (4) C: 77 (4)

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Exercise – Group-based 60-min exercise class focusing on muscle strength and balance training twice a week for 3 months for a total of 24 sessions |

Education – 60-min class once a month for three months for a total of three times. The classes focused on undernutrition, cognitive function and oral hygiene. |

Length of follow-up: 1 year

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 1 (2%) Reasons: 1 hip fracture

Control: N = 1 (2%) Reasons: 1 withdrew due to hospitalization

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 1 (2%) Reasons: 1 hip fracture

Control: N = 1 (2%) Reasons: 1 withdrew due to hospitalization |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%)

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 10 (20) C: 21 (41) RR 0.49 (95%CI 0.25-0.93)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 1 (2) C: 2 (4) |

Of all women aged 70 years or older, only 17% were included.

Fall were collected through diaries at the end of the one year follow-up. |

|

Lliffe, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: General practices

Country: United Kingdom

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention1: 411 Intervention2: 387 Control: 458

Important prognostic factors2: Only reported for the entire population together

Age (range): 73 (65-94)

Sex: 38% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Cannot be judged. |

1) Home-based Otago Exercise Programme (OEP) – 30 minutes of leg muscle strengthening and balance retraining exercises at home at least three times per week, and a walking plan for up to 30 minutes at a moderate pace two times per week for 24 weeks. 2) Community-based group exercise programme- 1-hour-long postural stability instructor-delivered group exercise class and two 30-minute home exercise sessions per week for 24 weeks. |

Usual care – participants were free to participate in any other non-trial-related exercise |

Length of follow-up: 18 months (6 month intervention and 12 follow-up)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention1: N = 158 (38%) Reasons: 27 at allocation; 13 GP excluded; 3 died; 43 through illness; 15 research burden; 17 other; 40 not known

Intervention2: N = 147 (38%) Reasons: 33 at allocation; 32 GP excluded; 3 died; 29 through illness; 12 research burden; 20 other; 18 not known

Control: N = 188 (41%) Reasons: 38 at allocation; 24 GP excluded; 4 died; 26 through illness; 30 research burden; 10 other; 56 not known

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention1: N = 158 (38%) Reasons: 27 at allocation; 13 GP excluded; 3 died; 43 through illness; 15 research burden; 17 other; 40 not known

Intervention2: N = 147 (38%) Reasons: 33 at allocation; 32 GP excluded; 3 died; 29 through illness; 12 research burden; 20 other; 18 not known

Control: N = 188 (41%) Reasons: 38 at allocation; 24 GP excluded; 4 died; 26 through illness; 30 research burden; 10 other; 56 not known |

1. Falls Measured as the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio During intervention I1: 0.80 I2: 0.81 C: 0.87 I1 vs C: RR 0.93 (95%CI 0.64-1.37) I2 vs C: RR 0.91 (95%CI 0.54-1.52) Post intervention I1: 0.54 I2: 0.57 C: 0.71 I1 vs C: RR 0.76 (95%CI 0.53-1.09) I2 vs C: RR 0.74 (95%CI 0.55-0.99)

2. Fractures Not reported

|

Randomisation took place at the general practices level.

Statistical analyses were adjusted for effects of size, size of practice, deprivation of practice, and clustering due to practice |

|

Suttanon, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 19 Control: 21

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 83 (5) C: 80 (6)

Sex: I: 32% M C: 43% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Exercise programme – standing balance and strengthening exercises and a graduated walking programme.

Participants and caregivers were encouraged to regular exercise (five days/week).

Participants in both groups continued with usual care and other activities while participating in their allocated programme. |

Control programme – education and information sessions on the topic of dementia and ageing.

Designed to provide the same number of home visits and phone calls as the exercise programme. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 8 (42%) Reasons: 3 refused to continue; 3 moved to care facility; 1 hospitalisation; 1 passed away

Control: N = 3 (14%) Reasons: 2 refused to continue; 1 moved to care facility

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 8 (42%) Reasons: 3 refused to continue; 3 moved to care facility; 1 hospitalisation; 1 passed away

Control: N = 3 (14%) Reasons: 2 refused to continue; 1 moved to care facility |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 1000 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 9 (47) C: 7 (33) RR 1.42 (95%CI: 0.66-3.06)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I: 3.10 C: 2.46 RR 1.00 (95%CI 0.42-2.39), adjusted for baseline measurements

2. Fractures Not reported |

Falls were reported by participants or caregivers at each of the home visits and follow-up phone calls. |

|

Yamada, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Japan

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 132 Control: 132

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 76 (9) C: 77 (8)

Sex: I: 40% M C: 45% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Multitarget stepping task combined twice a week for 24 weeks

30-minute physical exercise program (aerobic exercise, mild strength training and flexibility and balance exercises) |

Control – indoor walking program twice a week for 24 weeks

30-minute physical exercise program (aerobic exercise, mild strength training and flexibility and balance exercises) |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 20 (15%) Reasons: not stated

Control: N = 14 (11%) Reasons: not stated

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 20 (15%) Reasons: not stated

Control: N = 14 (11%) Reasons: not stated |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 13 (12) C: 39 (33) RR 0.33 (95%CI: 0.19-0.60)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I: Not reported C: Not reported RR 0.35 (95%CI 0.19-0.66)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 3 (3) C: 13 (11) RR 0.22 (95%CI: 0.06-0.80) |

No participant in either group received any specific instructions regarding activities undertaken outside the program or during the follow-up year.

Data on falls were collected through monthly diaries.

Fractures were ascertained through radiological evidence of fracture. |

|

Clemson, 2012 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel] Setting: Residents in metropolitan area

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention1: 107 Intervention2: 105 Control: 105

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I1: 82 (4) I2: 84 (4) C: 83 (4)

Sex: I1: 45% M I2: 46% M C: 45% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

1: LIFE programme Movements specifically prescribed to improve balance or increase strength embedded within everyday activities

2: Structured exercise Seven exercises for balance and six for lower limb strength using ankle cuff weights; three times a week

Both interventions programs were taught over five sessions with two booster sessions and two follow-up phone calls over a six month period. |

Control (gentle exercise) 12 gentle and flexibility exercises while seated, lying down, or standing while holding on.

Exercises were taught over two sessions with one booster sessions and six follow-up phone calls. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention1: N = 8 (7%) Reasons: 1 deceased; 1 too ill; 1 terminal illness; 2 injury or pain attributed to exercise; 2 partner need; 1 declined.

Intervention2: N = 9 (9%) Reasons: 3 deceased; 2 too ill; 1 terminal illness; 2 injury or pain attributed to exercise; 1 declined

Control: N = 14 (13%) Reasons: 3 deceased; 5 too ill; 2 terminal illness; 1 partner need; 3 declined

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention1: N = 8 (7%) Reasons: 1 deceased; 1 too ill; 1 terminal illness; 2 injury or pain attributed to exercise; 2 partner need; 1 declined.

Intervention2: N = 9 (9%) Reasons: 3 deceased; 2 too ill; 1 terminal illness; 2 injury or pain attributed to exercise; 1 declined

Control: N = 14 (13%) Reasons: 3 deceased; 5 too ill; 2 terminal illness; 1 partner need; 3 declined |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I1: 60 I2: 65 C: 71 I1 vs C: RR 0.83 (95%CI 0.67-1.03) I2 vs C: RR 0.92 (95%CI 0.75-1.12)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I1: 1.66 I2: 1.90 C: 2.28 I1 vs C: RR 0.69 (95%CI 0.48-0.99) I2 vs C: RR 0.81 (95%CI 0.56-1.17)

2. Fractures Not reported |

Potential limitations discussed by authors: The control group received less contact time than both interventions, which could have caused a bias, but we saw no difference in the return rates of fall surveillance diaries, so this is unlikely.

The control group had an intervention that could have diluted the effect of the outcomes. Since the control exercises were gentle, flexible, mostly non-weightbearing, and not upgraded by the therapists, their effect on fall reduction or balance would have been marginal, although we did observe some minimal strength improvements. |

|

Freiberger, 2012 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Germany

Source of funding: Commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention1: 63 Intervention2: 64 Intervention3: 73 Control: 80

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I1: 76 (4) I2: 75 (4) I3: 75 (4) C: 76 (4)

Sex: I1: 52% M I2: 64% M I3: 56% M C: 54% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

1) Strength and balance 2) Fitness (endurance training) 3) Multifaceted (fall risk education)

All lasting 16 weeks and including two 1-hour sessions per week. All interventions included strength and balance exercises. |

No intervention |

Length of follow-up: 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention1: N = 14 (22%) Reasons: Not stated Intervention2: N = 16 (25%) Reasons: Not stated Intervention3: N= 15 (18%) Reasons: Not stated

Control: N = 28 (35%) Reasons: Not stated

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention1: N = 14 (22%) Reasons: Not stated Intervention2: N = 16 (25%) Reasons: Not stated Intervention3: N= 15 (18%) Reasons: Not stated

Control: N = 28 (35%) Reasons: Not stated |

1. Falls Measured as the number of falls

Number of falls, rate ratio I1: 74 I2: 51 I3: 90 C: 82 I1 vs C: RR 0.97 (95%CI 0.58-1.62) I2 vs C: RR 0.68 (95%CI 0.40-1.16) I3 vs C: RR 0.94 (95%CI: 0.58-1.53)

2. Fractures Not reported |

Participants were recruited from a health insurance company membership database, which includes approximately 25% of the population.

Data on falls were collected monthly via fall calendars. |

|

Taylor, 2012 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: New Zealand

Source of funding: Commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention1: 233 Intervention2: 220 Control: 231

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I1: 75 (7) I2: 74 (6) C: 73 (6)

Sex: I1: 31% M I2: 25% M C: 24% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

1) Tai chi once a week 2) Tai chi twice a week for 20 weeks in a group setting |

Low-level exercise program for 20 weeks |

Length of follow-up: intervention for 20 weeks followed by 12 months follow-up

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention1: N = 53 (23%) Reasons: 42 partially returned, 11 no returns of the calendars

Intervention2: N = 46 (21%) Reasons: 36 partially returned, 10 no returns of the calendars

Control: N = 57 (25%) Reasons: 40 partially returned, 17 no returns of the calendars

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I1: 132 (60) I2: 111 (53) C: 140 (65) I1 vs C: RR 0.83 (95%CI 0.67-1.03) I2 vs C: RR 0.92 (95%CI 0.75-1.12)

Number of falls per person years, rate ratio I1: 1.55 (1.23-1.97) I2: 1.16 (0.92-1.48) C: 1.38 (1.24-1.53) I1 vs C: RR 1.13 (95%CI 0.87-1.45) I2 vs C: RR 0.84 (95%CI 0.64-1.11)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 1 (1) C: 0 (0) |

Falls were collected through monthly falls calendars. |

|

Fluid or nutrition therapy |

|||||||

|

Suominen, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Persons with Alzheimer disease living with a spouse

Country: Finland

Source of funding: Commercial and industry |

Inclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 50 Control: 44

Important prognostic factors2: Reported for analysed population (I: 40 and C: 38 participants) Age ± SD: I: 78 (6) C: 76 (6)

Sex: I: 53% M C: 47% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Tailored nutritional guidance with home visits during one year |

Written guide about nutrition in older adults and all community-provided normal care |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 10 (20%) Reasons: 1 moved to another city; 3 long-term care; 3 died; 3 food records not received

Control: N = 11 (22%) Reasons: 4 refusals; 1 long-term care; 1 died; 5 food records not received

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 10 (20%) Reasons: 1 moved to another city; 3 long-term care; 3 died; 3 food records not received

Control: N = 11 (22%) Reasons: 4 refusals; 1 long-term care; 1 died; 5 food records not received |

1. Falls Measured as the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of falls per person year, rate ratio I: 0.55 (95%CI: 0.34-0.83) C: 1.39 (95%CI: 1.04-1.82) RR 3.74 (95%CI 2.16-6.46)*, adjusted for age, sex and MMSE

2. Fractures Not reported |

*Calculated with the intervention group as reference. This results could because of adjustment for age, sex and MMSE not be included in the meta-analysis.

Authors did not stated how data on falls was collected. |

|

Vitamin D |

|||||||

|

Uusi-Rasi, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: home-dwelling women

Country: Finland

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 102 Control: 102

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 74 (3) C: 74 (3)

Sex: I: 0% M C: 0% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Vitamin D3 (800 IU/d) for 24 months |

Placebo |

Length of follow-up: 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 14 (14%) Reasons: 4 lost interest; 7 health reasons; 1 spouse illness; 2 died

Control: N = 7 (7%) Reasons: 2 lost interest; 3 health reasons; 2 died

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 14 (14%) Reasons: 4 lost interest; 7 health reasons; 1 spouse illness; 2 died

Control: N = 7 (7%) Reasons: 2 lost interest; 3 health reasons; 2 died |

1. Falls Measured as the rate of falls per 100 person-years

Number of falls per 100 person-years, rate ratio I: 132.1 C: 118.2 RR 1.08 (95%CI: 0.78-1.52)

2. Fractures Not reported |

NB: same population as Patil, 2015

The number of falls was obtained from prospective fall diaries returned monthly via mail, and details of each registered fall were ascertained by a telephone call. |

|

Environment/ assistive technology |

|||||||

|

Kamei, 2015 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Japan

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 67 Control: 63

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 75 (7) C: 75 (6)

Sex: I: 16% M C: 14% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Home Hazard modification education program (HHMP) (weekly for 2 hours for a total of four weeks)

Week 1: Education: elder’s fall and safety + exercise program Week 2: Education: food and nutrition + exercise program Week 3: Education and practice home hazard self-modification program (HHMP) using mock up and equipment + exercise program Week 4: Education and practices: foot self-care + exercise program |

Control program (weekly for 2 hours for a total of four weeks)

Week 1: Education: elder’s fall and safety + exercise program Week 2: Education: food and nutrition + exercise program Week 3: Education: aging and health + exercise program Week 4: Education and practices: foot self-care + exercise program |

Length of follow-up: 52 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 11 (16%) Reasons: Not stated

Control: N = 9 (14%) Reasons: Not stated

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 11 (16%) Reasons: Not stated

Control: N = 9 (14%) Reasons: Not stated |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 15 (22) C: 21 (33) RR 0.67 (95%CI: 0.38-1.18)

Number of falls per person years, hazard ratio I: Not reported C: Not reported RR 0.59 (95%CI: 0.31-1.15)

2. Fractures Only reported for indoor falls |

Falls were monitored prospectively using a daily falls calendar and self-report. Moreover, participants were interviewed twice: once at the 12 week follow-up as a midterm evaluation and then again at 52 weeks for the 1 year evaluation. |

|

Tchalla, 2013 |

Type of study: Minimized trial [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: France

Source of funding: Not stated |

Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 49 Control: 47

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 87 (7) C: 85 (6)

Sex: I: 23% M C: 23% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Home-based technologies coupled with teleassistance service (a nightlight path for preventing falls at home)

All participants undertook a fall reduction program following the initial Comprehensive Gerontological Assessment |

All participants undertook a fall reduction program following the initial Comprehensive Gerontological Assessment |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 4 (8%) Reasons: 2 died; 2 admissions to institution

Control: N = 4 (9%) Reasons: 1 died; 3 admissions to institution

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 4 (8%) Reasons: 2 died; 2 admissions to institution

Control: N = 4 (9%) Reasons: 1 died; 3 admissions to institution |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, odds ratio I: 15 (22) C: 21 (33) OR 0.37(95%CI: 0.15-0.88) adjusted for six variables (unclear which)

Cumulative incidence of falls I: 32.7% (95%CI: 21.2-46.6) C: 63.8% (95%CI: 49.5-76.0)

2. Fractures Not stated |

Because of the calculated OR and cumulative incidence these results could not be pooled with the data from the other trials.

Falls were collected by GPs and caregivers. |

|

Multifactorial interventions |

|||||||

|

Fairhall, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Australia

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 120 Control: 121

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 83 (6) C: 83 (6)

Sex: I: 33% M C: 32% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Multifactorial, interdisciplinary intervention – Targeting frailty characteristics with an individualised home exercise programme prescribed in 10 home visits from a physiotherapist and interdisciplinary management of medical, psychological and social problems.

Participants also received usual care. |

Control – Usual care available to older residents from community services and their general practitioner |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 13 (11%) Reasons: 12 died; 1 withdrew

Control: N = 12 (10%) Reasons: 10 died; 2 withdrew

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 13 (11%) Reasons: 12 died; 1 withdrew

Control: N = 12 (10%) Reasons: 10 died; 2 withdrew |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 365 patient days

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 72 (60) C: 67 (55) RR 1.08 (95%CI 0.87-1.35)

Number of falls per person, rate ratio I: 1.54 C: 1.50 RR 1.12 (95%CI 0.78-1.63)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 13 (11) C: 12 (10) RR 1.09 (95%CI: 0.52-2.30) |

Authors of the paper were employee at an insurance company.

Data on falls were collected through monthly calendars and follow-up telephone calls. |

|

Moller, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Urban and rural

Country: Sweden

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 80 Control: 73

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 81 (6) C: 81 (7)

Sex: I: 35% M C: 31% M

Groups comparable at baseline? No, less participants fell in the last 3 months |

1 Case management 2 General information (e.g. exercise, nutrition, social activities, healthy system and other) 3 Specific information (participant’s individual needs, medication, and more) 4 Safety and continuity

At least one home visit per month for twelve months |

Control |

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 24 (30%) Reasons: unclear

Control: N = 21 (29%) Reasons: unclear

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 24 (30%) Reasons: unclear

Control: N = 21 (29%) Reasons: unclear |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%)

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 43 (54) C: 35 (48) RR 1.12 (95%CI 0.82-1.53)

2. Fractures Not reported |

After the pilot study, the intervention was expanded in 2008 by also employing two physiotherapists. 61 of 80 participants from the intervention group also received visitors from physiotherapists.

Data on falls was collected every three months. |

|

Palvanen, 2014 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Fall prevention clinics

Country: Finland

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

At least one of the following risk factors for falls and injuries:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 661 Control: 653

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 77 (6) C: 77 (6)

Sex: I: 14% M C: 14% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Multifactorial, individualized 12-month falls prevention program concentrating on strength and balance training, medical review and referrals, medication review, proper nutrition (calcium, vitamin D), and home hazard assessment and modification. Individually tailored preventive measures judged necessary at the baseline assessment. |

Control group – a general injury prevention brochure

|

Length of follow-up: 12 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N = 72 (11%) Reasons: 35 illness/sickness; 31 refusal to continue; 3 died; 3 other reason

Control: N = 97 (15%) Reasons: 54 illness/sickness; 29 refusal to continue; 8 died; 4 moved; 2 other reason

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N = 72 (11%) Reasons: 35 illness/sickness; 31 refusal to continue; 3 died; 3 other reason

Control: N = 97 (15%) Reasons: 54 illness/sickness; 29 refusal to continue; 8 died; 4 moved; 2 other reason |

1. Falls Measured as the number of fallers, n (%) and the rate of falls per 100 person years

Number of fallers, risk ratio I: 296 (45) C: 349 (53) RR 0.84 (95%CI 0.75-0.94)

Number of falls per 100 person years, rate ratio I: 95 C: 131 RR 0.72 (95%CI 0.61-0.86)

2. Fractures Measured as the number of participants with a fracture related to a fall, n (%)

I: 33 (5) C: 42 (6) RR 0.78 (95%CI: 0.50-1.21) |

The Chaos Clinic professionals (who were not blinded to group allocation, as noted above) recorded the number of falls and fall-related injuries in three month intervals, by phone interview at 3 and 9 months, and at the follow-up visit at the Clinic at 6 and 12 months. |

|

Lee, 2013 |

Type of study: RCT [parallel]

Setting: Community

Country: Taiwan

Source of funding: Non-commercial |

Inclusion criteria:

Fulfilled 1 of the following criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

N total at baseline: Intervention: 313 Control: 303

Important prognostic factors2: Age ± SD: I: 75 (7) C: 76 (7)

Sex: I: 53% M C: 56% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |