Huiddesinfectie

Uitgangsvraag

What is the effect of different preoperative skin antiseptic solutions and concentrations on the risk of surgical site infections in surgical patients?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik voorafgaand aan alle chirurgische interventies chloorhexidine 2.0-2.5% alcohol 70% voor het desinfecteren van de huid van de patiënt, ter preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties.

- Voor schone chirurgische interventies kan geen specifieke concentratie chloorhexidine-alcohol worden aanbevolen.

Deze aanbeveling is alleen van toepassing voor desinfectie van de huid. Voor desinfectie van de slijmvliezen en het peri-oculaire gebied verwijzen wij naar de SRI-richtlijn ‘Desinfectie huid- en slijmvliezen & Puncties.’

Overwegingen

Summary of the evidence

There is a benefit of the use of either 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol or 1.5% olanexidine (evidence from only one RCT) in the reduction of SSI compared with aqueous iodine in any type of surgery. The results of 0.5% CHG-alcohol and 4.0% CHG-alcohol also suggests a beneficial effect but remain non-significant with a wide confidence interval. This may be due to limited evidence for 0.5% CHG-alcohol and 4.0% CHG-alcohol. Aqueous CHG and iodine-alcohol showed comparable effects compared to aqueous iodine. Olanexidine, a new antiseptic solution, was found to be most effective, but, due to its novelty, investigated in only one RCT.

Incidence SSI

An overall SSI rate of 12,1% was found, which is high compared to recent literature on SSI rate across all surgery. This can be explained by the 20% SSI rate reported by the largest included RCT undertaken in seven low-income and middle-income countries. NIHR 2021 et al. reported 1163 (20,1%) SSI in 5788 patients undergoing abdominal surgery (CDC wound classification II, III or IV) with a skin incision of five centimeter or greater. Without this RCT, all other included studies report a total number of 981 SSI in 11,947 patients (8,2%).

The overall level of evidence for the outcome SSI was graded as moderate (downgraded because of imprecision) and in one comparison high.

Adverse events

The potential adverse effects were also investigated. Only ten of the 33 included studies reported adverse skin reactions, with five of the studies reporting actual events. These individual studies found no substantial difference in the incidence of adverse events between the different antiseptic solutions. Although there is evidence suggesting a high concentration (4.0%) of CHG-alcohol should be avoided since it is known to be irritant in high concentrations, the evidence was too scarce to analyse this properly.

Subgroup: clean surgery

For the surgical wound classification, the CDC classification was used to grade the degree of intraoperative microbial contamination. Clean surgery is defined as “an uninfected operative wound in which no inflammation is encountered and the respiratory, alimentary, genital, or uninfected urinary tract is not entered.” (Mangram 1999)

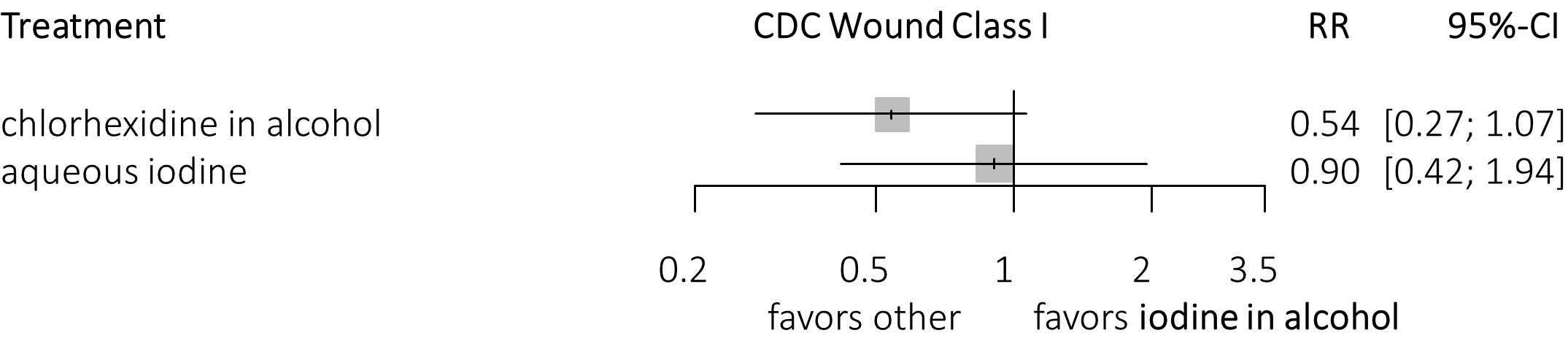

In clean surgery only, a potential benefit of the different concentrations CHG-alcohol over aqueous iodine is found. These effects were not significant due to a wide confidence interval, possibly because of the low incidence of SSI and a relatively small number of patients. The incidence of SSI in clean surgery only studies was 4.8 % (158 SSI in 3301 patients), whereas after excluding these studies, the incidence of SSI was 13.1% (2044 SSI in 15,562 patients) for non-clean surgery. When clustering the different concentrations of CHG-alcohol into one group CHG-alcohol is significantly more effective than aqueous iodine. Compared to iodine-alcohol, clustering CHG-alcohol shows a benefit, however this remains non-significant (figure 3a and figure 3b).

It could be assumed that skin antisepsis would be equally effective in clean and non-clean surgery when SSI only originates from the skin. However, in non-clean surgery, spillage from contaminated surgical areas to the wound surface, wound edges and surrounding skin also plays a role. Antiseptics are toxic to bacteria and therefore aid their mechanical removal. Alcohol-based antiseptic solutions have durable effects more than six hours after skin preparation with broader spectrum antimicrobial activity after surgical spillage.

International guidelines

In contrast to previous international recommendations, 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol was found to be superior to other concentrations of CHG-alcohol. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Berrios-Torres 2017) advises alcohol-based solutions, whereas the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2019) and World Health Organisation guidelines (WHO 2018) recommend explicitly CHG in alcohol as antiseptic for reduction of SSI. Since publication of these guidelines, many new RCTs have been conducted investigating various types of antiseptic solutions. In this guideline, seven additional studies were added compared to the NICE guideline, all published since 2019; and eleven additional studies compared to the WHO guideline since 2016.

Here, we focus on skin preparation, however, one should understand that it is not the only preventative measure for SSI. Other measures, such as timing and dosing of surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis, normovolemia, irrigation of operative wound, etc., are of equal importance. Most of the included studies adhere to best practice guidelines, but not all studies included in the literature mentioned this, and heterogeneity of other preventative measures are inevitable.

Patient preferences

None of the described preparation methods showed increased risk of skin irritation or other harmful effects on patient-related outcomes. However, individual experience with alcohol, aqueous, iodine or chlorhexidine solutions with the skin/skin disorders might result in a preference of the patient.

Resource use

There are no cost-effective studies available. However, SSI is a costly complication and therefore, the prevention of SSI contributes more to cost reduction than the difference in costs between individual antiseptic solutions.

Sustainability, feasibility, and implementation

There are no issues regarding to the feasibility of the different skin preparation solutions for implementation in clinical practice.

Rationale of the recommendation

There is a benefit of all different CHG-alcohol concentrations over iodine in the prevention of SSI, in adult patients undergoing surgical procedures, in particular 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol. However, no difference of effectiveness is found between different concentrations of CHG-alcohol for clean surgery. Although, when clustering the different concentrations into one group a benefit is seen over aqueous iodine. Olanexidine 1.5% also shows a potential benefit over iodine in the prevention of SSI in clean-contaminated surgery, though this is based on one single randomised trial and further investigation is needed.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Surgical site infections (SSI) are the most common postoperative complications and substantially increase morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. The efficacy of preoperative skin antiseptics in the prevention of SSIs is well established, but there remains uncertainty about which antiseptic solution and concentration is most effective and international guidelines show discrepancy.

Conclusies

Surgical site infections (SSI)

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 4.0%

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with CHG-alcohol 4.0% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0%

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with aqueous CHG 4.0% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. aqueous iodine

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with aqueous iodine in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. iodine-alcohol

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with iodine-alcohol in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. olanexidine 1.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

Olanexidine 1.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with CHG-alcohol 0.5% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 4.0%

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 2% likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with CHG-alcohol 4.0% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0%

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 2% likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with aqueous CHG 4.0% in surgical patients, but the evidence is very uncertain. |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. aqueous iodine

|

High GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% results in a reduction of SSI when compared with aqueous iodine in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. iodine-alcohol

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with iodine-alcohol in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. olanexidine 1.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

Olanexidine 1.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0%

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% likely reduces SSI when compared with aqueous CHG 4.0% in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. aqueous iodine

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% likely reduces SSI when compared with aqueous iodine in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. iodine-alcohol

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG 4.0% likely reduces SSI when compared with iodine-alcohol in surgical patients. |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. olanexidine 1.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

Olanexidine 1.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with CHG-alcohol 4.0% in surgical patients. |

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. aqueous iodine

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG 4.0% likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with aqueous iodine in surgical patients. |

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. iodine-alcohol

|

Moderate GRADE |

CHG 4.0% likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with iodine-alcohol in surgical patients. |

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. olanexidine 1.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

Olanexidine 1.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with aqueous CHG 4.0% in surgical patients. |

Aqueous iodine vs. iodine-alcohol

|

Moderate GRADE |

Aqueous iodine likely results in little to no difference on SSI when compared with iodine-alcohol in surgical patients. |

Aqueous iodine vs. olanexidine 1.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

Olanexidine 1.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with aqueous iodine in surgical patients. |

Iodine-alcohol vs. olanexidine 1.5%

|

Moderate GRADE |

Olanexidine 1.5% likely reduces SSI when compared with iodine-alcohol in surgical patients. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Thirty-three studies were included in the analysis of the literature, of which 27 RCTs with 17,735 patients were included in the network meta-analysis (NMA). In total, 37 comparisons of treatments were included in the systematic review.

One RCT compared 0.5% CHG-alcohol and 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol (Casey, 2015). Three studies compared 0.5% CHG-alcohol with aqueous iodine (Srinivas, 2015; Abreu, 2014; Brown, 1984). Four RCTs compared 0.5% CHG-alcohol and iodine alcohol (Shadid, 2019; Perek, 2013; Cheng, 2009; Veiga, 2008). Eleven studies compared 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol and aqueous iodine (NIHR, 2021; Luwang, 2021; Danasekaran, 2017; Springel, 2017; Xu, 2017; Bibi, 2015; Kunkle, 2015; Yeung, 2013; Darouiche, 2010; Sistla, 2010; Saltzman, 2009). Seven RCTs compared 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol and iodine alcohol (Ritter, 2020; Broach, 2017; Xu, 2017; Tuuli, 2016; Ngai, 2015; Savage, 2012; Saltzman, 2009). Three RCTs compared 4.0% CHG-alcohol and aqueous iodine (Gezer, 2020; Paocharoen, 2009; Bibbo, 2005). One RCT compared aqueous CHG and aqueous iodine (Park, 2017). Six RCTs compared aqueous iodine and iodine-alcohol (Dior, 2020; Xu, 2017; Saltzman, 2009; Segal, 2002; Howard, 1991; Gilliam, 1990) and one RCT compared aqueous iodine and olanexidine 1.5% (Obara, 2020).

Twenty-seven different solutions were used as skin antiseptics. For the analysis, RCTs using 2.0% and 2.5% CHG in 70% isopropyl alcohol (IPA), alcohol or ethanol were grouped as 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol. CHG 0.5% in 70% IPA, alcohol or ethanol were pooled into 0.5% CHG-alcohol. The group 4.0% CHG-alcohol consisted of studies using 4.0% CHG in 70% IPA or alcohol. All formulations of aqueous iodine, aqueous povidone iodine or aqueous iodophor were combined into one group, also for iodine-alcohol, povidone iodine-alcohol and iodophor in alcohol.

1. Surgical site infections (SSI)

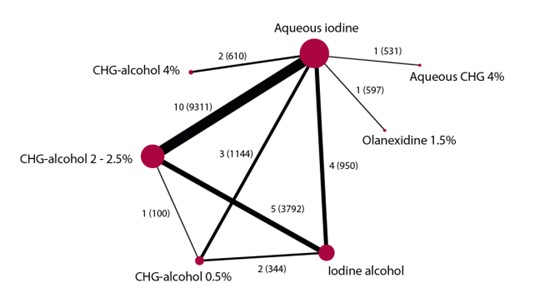

A network meta-analysis was carried out to investigate the effect of the different treatment modalities on SSI. In total, 27 RCTs contributed to the overall NMA. A network graph, including all studies is presented in figure 1. Results from the NMA are presented in the forest plots (figure 2).

Figure 1. Network graph of all studies in network meta-analysis (Jalalzadeh, 2022)

1.1 Aqueous iodine versus 0.5% CHG-alcohol

In total, three studies (n=1144) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of aqueous iodine versus 0.5% CHG-alcohol on SSI (Srinivas, 2015; Abreu, 2014; Brown, 1984). The overall network RR was 0.69 (95% CI 0.47, 1.02), a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring 0.5% CHG-alcohol.

1.2 Aqueous iodine versus 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol

In total, ten studies (n=9311) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of aqueous iodine versus 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol on SSI (NIHR 2021, 2021; Luwang, 2021; Danasekaran, 2017; Springel, 2017; Xu, 2017; Bibi, 2015; Kunkle, 2015; Yeung, 2013; Darouiche, 2010; Sistla, 2010). One study (Saltzman, 2009) reported no SSI in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA. The overall network RR was 0.75 (95% CI 0.61, 0.92), a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring 2.0-2.5% CHG-alcohol.

1.3 Aqueous iodine versus 4.0% CHG-alcohol

In total, two studies (n=610) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of aqueous iodine versus 4.0% CHG-alcohol on SSI (Gezer, 2020; Paocharoen, 2009). One study (Bibbo, 2005) reported no SSI in both arms and was thus excluded from the NMA. The overall network RR was 0.67 (95% CI 0.32, 1.40), a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring 4.0% CHG-alcohol.

1.4 Aqueous iodine versus aqueous CHG

One study (n=581) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of aqueous iodine versus aqueous CHG on SSI (Park, 2017). The overall network RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.43, 2.01), this difference was not significant nor clinically relevant.

1.5 Aqueous iodine versus iodine-alcohol

In total, four studies (n=950) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of aqueous iodine versus iodine-alcohol on SSI (Dior, 2020; Xu, 2017; Segal, 2002; Howard, 1991). Two studies (Saltzman, 2009; Gilliam, 1990) reported no SSI in both arms and were thus excluded from the NMA. The overall network RR was 0.97 (95% CI 0.73, 1.29), this difference was not significant nor clinically relevant.

1.6 Aqueous iodine versus olanexidine 1.5%

One study (n=597) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of aqueous iodine versus olanexidine 1.5% on SSI (Obara, 2020). The overall network RR was 0.49 (95% CI 0.26, 0.92), a significant and clinically relevant difference favoring olanexidine 1.5%.

1.7 CHG-alcohol 0.5% versus CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5%

One study (n=100) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of CHG-alcohol 0.5% versus CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% on SSI (Casey, 2015). The overall network RR was 0.93 (95% CI 0.60, 1,43), a non-significant nor clinically relevant difference.

1.8 CHG-alcohol 0.5% versus Iodine-alcohol

In total, two studies (n=344) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of CHG-alcohol 0.5% versus iodine-alcohol on SSI (Perek, 2013; Veiga, 2008). Two studies (Shadid, 2019; Cheng, 2009) reported no SSI in both arms and were thus excluded from the NMA. The overall network RR was 0.71 (95% CI 0.45, 1.14), a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring CHG-alcohol 0.5%.

1.9 CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% versus Iodine-alcohol

Five studies (n=3792) contributed with a direct comparison to the NMA investigating the effect of CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% versus Iodine-alcohol on SSI (Ritter, 2020; Broach, 2017; Xu, 2017; Tuuli, 2016; Ngai, 2015). Two studies (Savage, 2012; Saltzman, 2009) reported no SSI in both arms and were thus excluded from the NMA. The overall network RR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.60, 1.00), a non-significant but clinically relevant difference favoring CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5%.

1.10 Results NMA

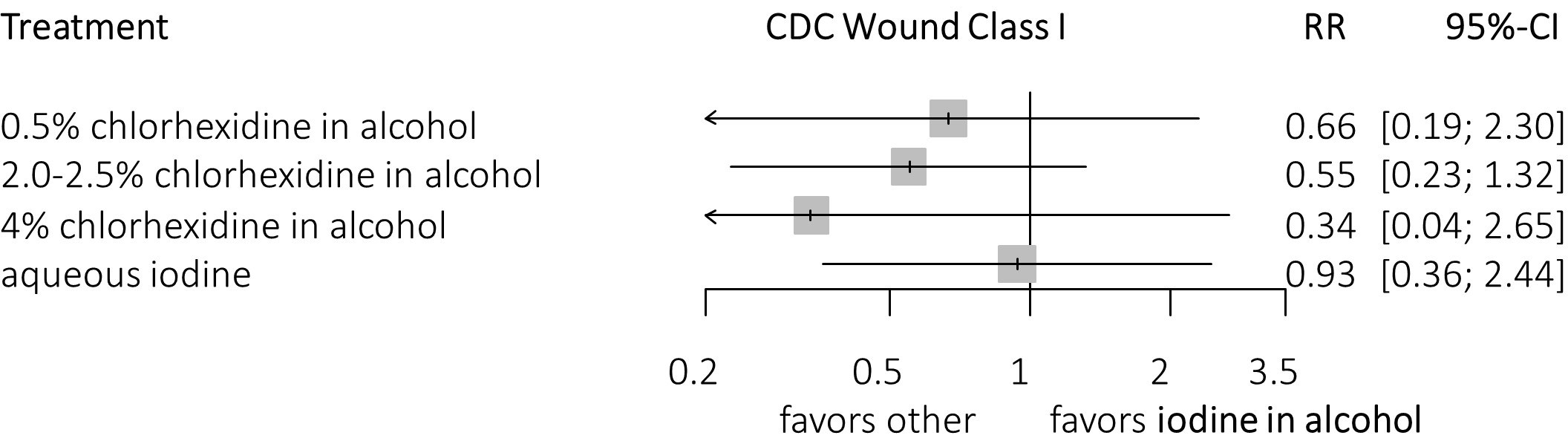

Results from the NMA are presented in de forest plots shown in Figure 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Forest plots

The forest plots show the efficacy of different skin preparation solutions and concentrations in the prevention of SSIs compared with aqueous iodine. Data are RR with corresponding 95% CI. (A) Efficacy for any type of surgery. (B) Efficacy for clean surgery. (C) Efficacy for clean surgery, clustering of chlorhexidine in alcohol. (D) Efficacy for non-clean surgery, excluding studies looking only at clean surgical procedures (i.e., only wound class 1).

Figure3. Forest plots

3a. Compared with iodine in alcohol (clean surgery).

3b. Compared with iodine in alcohol (clean surgery), clustering of CHG-alcohol.

2. Adverse events

Since the number of events does not meet the optimal information size, we did not grade the body of evidence for the outcome adverse events. However, since it may hold important clinical information, the type of adverse skin events is presented across the different interventions in table 1. Adverse events of the skin related to the skin preparation solutions were mentioned in 10 RCTs (NIHR, 2021; Obara, 2020; Broach, 2017; Park, 2017; Tuuli, 2016; Bibi, 2015; Srinivas, 2015; Yeung, 2013; Darouiche, 2010; Paocharoen, 2009). Five studies (NIHR, 2021; Broach, 2017; Park, 2017; Srinivas, 2015; Yeung, 2013) reported no adverse events, the other five studies reported a total of 59 mild adverse events, mainly erythema, pruritus, dermatitis, skin irritation or mild allergic symptoms. None of the RCTs found a significant difference in adverse events in the groups. The results are depicted in table 1.

Table 1. Number of adverse skins events related to study medication

|

Study |

Comparison |

Adverse skin events related to study medication |

|

NIHR 2020 |

CHG-alcohol 2.0% |

No events |

|

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

No events |

|

|

Obara 2020 |

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

5 patients with erythema, pruritus or dermatitis |

|

Olanexidine 1.5% |

5 patients with erythema, pruritus or dermatitis |

|

|

Broach 2017 |

CHG-alcohol 2.0% |

No events |

|

Iodine-alcohol 0.7% AI |

No events |

|

|

Park 2017 |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

No events |

|

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

No events |

|

|

Tuuli 2016 |

CHG-alcohol 2.0% |

17 patients with adverse skin reactions with erythema at operative site, allergic skin reaction or skin irritation or allergic skin reaction |

|

Iodine-alcohol 0.7% AI |

19 patients with erythema at operative site, skin irritation, allergic skin reaction or skin irritation or allergic skin reaction |

|

|

Bibi 2015 |

CHG-alcohol 2.0% |

No events |

|

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

2 patients with mild allergic symptoms |

|

|

Srinivas 2015 |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% |

No events |

|

Aqueous iodine 0.5% AI |

No events |

|

|

Yeung 2013 |

CHG-alcohol 2.0% |

No events |

|

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

No events |

|

|

Darouiche 2010 |

CHG-alcohol 2.0% |

3 patients with pruritus, erythema, or both around the surgical wound |

|

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

3 patients with pruritus, erythema, or both around the surgical wound |

|

|

Paocharoen 2009 |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

No events |

|

Aqueous iodine 1% AI |

2 patients with skin irritation |

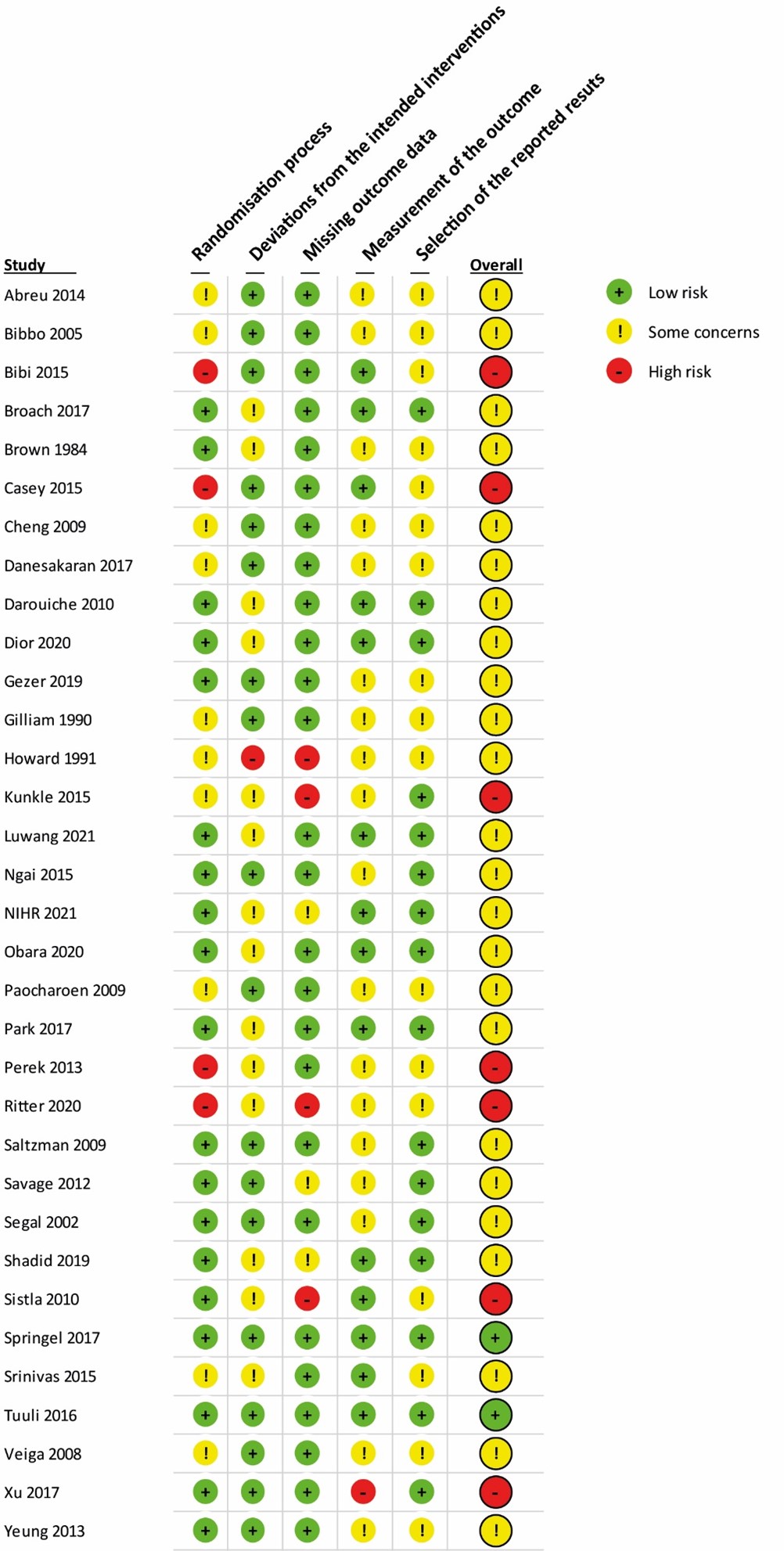

Level of evidence of the literature

The GRADE approach for rating the certainty of estimates of treatment effects was used. Since all included studies are randomized controlled trials, the rating for the GRADE starts high for all comparisons. Each comparison can be downgraded due to one of the following reasons:

- Risk of bias: Of the 27 studies included in the network meta-analysis, six had an overall “High risk of bias”. Due to the network meta-analysis, this may influence all the network estimates of all comparison. We performed a (network) sensitivity meta-analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias. The results were comparable with the overall analysis, and downgrading for risk of bias was not needed. *

- Inconsistency: When comparing the effect estimates of the direct and indirect results after netsplitting, we see consistency over all comparisons (Appendix 6)

- Imprecision: For relative risks that cross the null-effect threshold (RR 1) we downgraded with one. If the threshold is not crossed, we did not downgrade. The only exception to this is the comparison Olanexidine 1.5% versus aqueous iodine. We see a large effect that does not cross the threshold. However, the optimal information size is not met (based on one RCT),47 which results in -1 downgrade for imprecision.

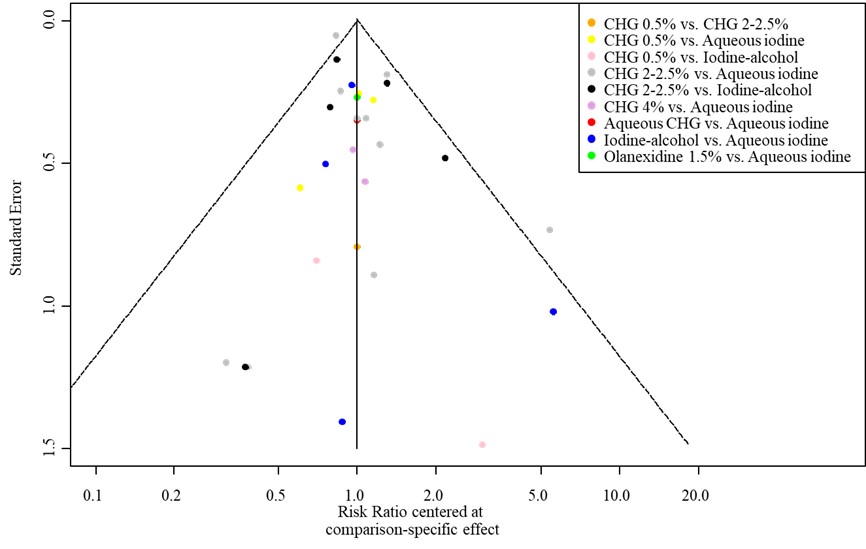

- Publication bias: The comparison-adjusted funnel plot showed no sign of small-study effects (see funnel plot).

* Of the 27 studies included in the NMA, six had an overall “High risk of bias”. Due to the nature of a NMA, this may influence all the network estimates of all comparisons. In a sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias the results were comparable with the main analysis, thus downgrading for risk of bias was not needed. In addition, some comparisons were also downgraded because of imprecision. Overall, the certainty of the treatments effects was deemed moderate, except for one comparison, which was deemed high (CHG 2.0-2.5% vs aqueous iodine).

Table 2. Level of evidence per comparison for the outcome surgical site infections

|

Comparison |

Reasons for downgrading |

||

|

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Network meta-analysis |

|

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% |

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

- |

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. aqueous iodine |

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. iodine-alcohol |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. aqueous iodine |

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. iodine-alcohol |

No downgrade

|

-1 imprecision |

No downgrade |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

-

|

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs aqueous CHG 4.0% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. aqueous iodine |

-1 imprecision

|

- |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. iodine-alcohol |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. aqueous iodine |

-1 imprecision

|

- |

-1 imprecision |

|

Aqueous 4.0% vs. iodine-alcohol |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

Aqueous 4.0% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

Aqueous iodine vs. iodine-alcohol |

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision |

-1 imprecision |

|

Aqueous iodine vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

-1 imprecision

|

- |

-1 imprecision |

|

Iodine-alcohol vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

-1 imprecision

|

-1 imprecision |

If only direct or indirect evidence is available for a given comparison, the network quality rating will be based on that estimate. When, for a particular comparison, both direct and indirect evidence are available, we used the highest of the two quality ratings as the quality rating for the NMA estimate. The quality of the network estimate can be upgraded if precision is greater than direct or indirect estimates.

Table 3. GRADE table

|

Comparison |

Direct evidence |

Indirect evidence |

Network meta-analysis |

|||

|

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

Relative Risk (95%CI) |

Certainty of evidence |

|

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% |

3.00 (0.61 - 14.74) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.83 (0.54 - 1.29) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.93 (0.60 - 1.43) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

- |

- |

1.04 (0.45 - 2.39) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.04 (0.45 - 2.39) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0% |

- |

- |

0.74 (0.31 - 1.79) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.74 (0.31 - 1.79) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. aqueous iodine |

0.68 (0.45 - 1.03) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.78 (0.26 - 2.38) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.69 (0.47 - 1.02) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. iodine-alcohol |

0.33 (0.08 - 1.44) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.78 (0.47 - 1.29) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.71 (0.45 - 1.14) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 0.5% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

- |

1.43 (0.68 - 3.01) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.43 (0.68 - 3.01) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

- |

- |

1.12 (0.52 - 2.41) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.12 (0.52 - 2.41) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0% |

- |

- |

0.81 (0.36 - 1.79) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.81 (0.36 - 1.79) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. aqueous iodine |

0.77 (0.62 - 0.97) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

0.62 (0.36 - 1.06) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.75 (0.61 - 0.92) |

ÅÅÅÅ high |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. iodine-alcohol |

0.76 (0.57 - 1.03) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.78 (0.46 - 1.34) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.77 (0.60 - 1.00) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

- |

1.54 (0.79 - 3.00) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.54 (0.79 - 3.00) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. aqueous CHG 4.0% |

- |

- |

0.71 (0.25 - 2.08) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.71 (0.25 - 2.08) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. aqueous iodine |

0.77 (0.32 - 1.41) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

- |

- |

0.77 (0.32 - 1.41) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. iodine-alcohol |

- |

- |

0.69 (0.31 - 1.53) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.69 (0.31 - 1.53) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

- |

1.38 (0.52 - 3.65) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.38 (0.52 - 3.65) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. aqueous iodine |

0.93 (0.43 - 2.01) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

- |

- |

0.93 (0.43 - 2.01) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. iodine-alcohol |

- |

- |

0.96 (0.42 - 2.19) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.96 (0.42 - 2.19) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

Aqueous CHG 4.0% vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

- |

- |

1.91 0.70 - 5.20) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.91 0.70 - 5.20) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

Iodine-alcohol vs. aqueous iodine |

0.86 (0.53 - 1.39) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

1.04 (0.71 - 1.52) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

0.97 (0.72 - 1.30) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

Olanexidine 1.5% vs. aqueous iodine |

0.49 (0.26 - 0.92) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

- |

- |

0.49 (0.26 - 0.92) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

|

Iodine-alcohol vs. olanexidine 1.5% |

. |

- |

2.00 (0.99 - 4.00) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

2.00 (0.99 - 4.00) |

ÅÅÅO moderate |

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

P: Adults undergoing any surgical procedure

I: Antiseptic skin preparation agents (CHG, iodine or olanexidine) or concentrations

in aqueous and alcohol-based solutions.

C: Other antiseptic skin preparation agents (CHG, iodine or olanexidine) or

concentrations in aqueous and alcohol-based solutions.

O: Surgical site infections (SSI) (superficial, deep, and organ SSI); adverse events of the intervention (e.g., allergic reactions).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered occurrence of surgical site infections as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and adverse events (e.g., allergic reactions) as an important outcome measure for clinical decision making.

The working group defined a threshold of 10% for continuous outcomes and a relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes of <0.80 and >1.25 as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases [Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com)] were searched with relevant search terms until 23-11-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 2631 hits.

RCTs were included when comparing two or more antiseptic skin preparation agents (CHG, iodine or olanexidine) or concentrations in aqueous and alcohol-based solutions in adults undergoing surgical procedures in the operating theatre that reported SSI rates.

Sixty-eight studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 35 studies were excluded (see the exclusion table with reasons for exclusion), and 33 studies were included.

Results

Thirty-three studies were included in the final analysis. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Abreu D, Campos E, Seija V, Arroyo C, Suarez R, Rotemberg P, Guillama F, Carvalhal G, Campolo H, Machado M, Decia R. Surgical site infection in surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparison of two skin antiseptics and risk factors. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014 Dec;15(6):763-7. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.174. PMID: 25372452.

- Berrios-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, Leas B, Stone EC, Kelz RR, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784-91.

- Bibbo C, Patel DV, Gehrmann RM, Lin SS. Chlorhexidine provides superior skin decontamination in foot and ankle surgery: a prospective randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:204-8.

- Bibi S, Shah SA, Qureshi S, Siddiqui TR, Soomro IA, Ahmed W, et al. Is chlorhexidine-gluconate superior than Povidone-Iodine in preventing surgical site infections? A multicenter study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(11):1197-201.

- Brown TR, Ehrlich CE, Stehman FB, Golichowski AM, Madura JA, Eitzen HE. A clinical evaluation of chlorhexidine gluconate spray as compared with iodophor scrub for preoperative skin preparation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984 Apr;158(4):363-6. PMID: 6710300.

- Broach RB, Paulson EC, Scott C, Mahmoud NN. Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Alcohol-based Preparations for Surgical Site Antisepsis in Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;266(6):946-51.

- Casey A, Itrakjy A, Birkett C, Clethro A, Bonser R, Graham T, Mascaro J, Pagano D, Rooney S, Wilson I, Nightingale P, Crosby C, Elliott T. A comparison of the efficacy of 70% v/v isopropyl alcohol with either 0.5% w/v or 2% w/v chlorhexidine gluconate for skin preparation before harvest of the long saphenous vein used in coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Infect Control. 2015 Aug;43(8):816-20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.034. Epub 2015 May 13. Erratum in: Am J Infect Control. 2018 Mar 21;: PMID: 25979197.

- Cheng K, Robertson H, St Mart JP, Leanord A, McLeod I. Quantitative analysis of bacteria in forefoot surgery: a comparison of skin preparation techniques. Foot Ankle Int. 2009 Oct;30(10):992-7. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0992. PMID: 19796594.

- Danasekaran G, Rasu S, Palani M. A study of comparative evaluation of preoperative skin preparation with chlorhexidine alcohol versus povidone iodine in prevention of surgical site infections. J Evid Based Med Healthcare. 2017;4:41.

- Darouiche RO, Wall MJ, Jr., Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, Carrick MM, et al. Chlorhexidine-Alcohol versus Povidone-Iodine for Surgical-Site Antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18-26.

- Dior UP, Kathurusinghe S, Cheng C, Reddington C, Daley AJ, Ang C, et al. Effect of Surgical Skin Antisepsis on Surgical Site Infections in Patients Undergoing Gynecological Laparoscopic Surgery: A Double-Blind Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(9):807-15

- Gezer S, Yalvac HM, Gungor K, Yucesoy I. Povidone-iodine vs chlorhexidine alcohol for skin preparation in malignant and premalignant gynaecologic diseases: A randomized controlled study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;244:45-50.

- Gilliam DL, Nelson CL. Comparison of a one-step iodophor skin preparation versus traditional preparation in total joint surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990(250):258-60.

- Howard R. Comparison of a 10-minute aqueous iodophor and 2-minute water-insoluble iodophor in alcohol preoperative skin preparation. Compl Orthop. 1991;19:134-6.

- Kunkle CM, Marchan J, Safadi S, Whitman S, Chmait RH. Chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine at cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(5):573-7.

- Luwang AL, Saha PK, Rohilla M, Sikka P, Saha L, Gautam V. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine as preoperative skin antisepsis for prevention of surgical site infection in cesarean delivery-a pilot randomized control trial. Trials. 2021 Aug 17;22(1):540. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05490-4. PMID: 34404473; PMCID: PMC8369632.

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(2):97-96. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(99)70088-X. PMID: 10196487.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2019 exceptional surveillance of surgical site infections: prevention and treatment (NICE guideline NG125)

- NIHR Global Research Health Unit on Global Surgery. Reducing surgical site infections in low-income and middle-income countries (FALCON): a pragmatic, multicentre, stratified, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021 Nov 6;398(10312):1687-1699. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01548-8. Epub 2021 Oct 25. PMID: 34710362; PMCID: PMC8586736.

- Obara H, Takeuchi M, Kawakubo H, Shinoda M, Okabayashi K, Hayashi K, et al. Aqueous olanexidine versus aqueous povidone-iodine for surgical skin antisepsis on the incidence of surgical site infections after clean-contaminated surgery: a multicentre, prospective, blinded-endpoint, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(11):1281-9.

- Paocharoen V, Mingmalairak C, Apisarnthanarak A. Comparison of surgical wound infection after preoperative skin preparation with 4.0% chlorhexidine [correction of chlohexidine] and povidone iodine: a prospective randomized trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(7):898-902.

- Park HM, Han SS, Lee EC, Lee SD, Yoon HM, Eom BW, et al. Randomized clinical trial of preoperative skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine. Br J Surg. 2017;104(2):e145-e50.

- Perek, Bartłomiej & Lipski, Adam & Stefaniak, Sebastian & Jemielity, Marek. (2013). Comparative analysis of the antiseptic effectiveness of two commercially available skin disinfectants in cardiac surgery-a preliminary report. Kardiochirurgia i Torakochirurgia Polska. 10. 177-181. 10.5114/kitp.2013.36145. Shadid MB, Speth MJGM, Voorn GP, Wolterbeek N. Chlorhexidine 0.5%/70% Alcohol and Iodine 1%/70% Alcohol Both Reduce Bacterial Load in Clean Foot Surgery: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019 Mar;58(2):278-281. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2018.08.042. Epub 2019 Jan 3. PMID: 30612875.

- Ritter B, Herlyn PKE, Mittlmeier T, Herlyn A. Preoperative skin antisepsis using chlorhexidine may reduce surgical wound infections in lower limb trauma surgery when compared to povidone-iodine - a prospective randomized trial. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48(2):167-72.

- Saltzman MD, Nuber GW, Gryzlo SM, Marecek GS, Koh JL. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1949-53.

- Savage JW, Weatherford BM, Sugrue PA, Nolden MT, Liu JC, Song JK, et al. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in lumbar spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):490-4.

- Segal CG, Anderson JJ. Preoperative skin preparation of cardiac patients. AORN J. 2002;76(5):821-8.

- Shadid MB, Speth M, Voorn GP, Wolterbeek N. Chlorhexidine 0.5%/70% Alcohol and Iodine 1%/70% Alcohol Both Reduce Bacterial Load in Clean Foot Surgery: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;58(2):278-81.

- Sistla SC, Prabhu G, Sistla S, Sadasivan J. Minimizing wound contamination in a 'clean' surgery: comparison of chlorhexidine-ethanol and povidone-iodine. Chemotherapy. 2010;56(4):261-7.

- Springel EH, Wang XY, Sarfoh VM, Stetzer BP, Weight SA, Mercer BM. A randomized open-label controlled trial of chlorhexidine-alcohol vs povidone-iodine for cesarean antisepsis: the CAPICA trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(4):463 e1- e8.

- Srinivas A, Kaman L, Raj P, Gautam V, Dahiya D, Singh G, Singh R, Medhi B. Comparison of the efficacy of chlorhexidine gluconate versus povidone iodine as preoperative skin preparation for the prevention of surgical site infections in clean-contaminated upper abdominal surgeries. Surg Today. 2015 Nov;45(11):1378-84. doi: 10.1007/s00595-014-1078-y. Epub 2014 Nov 9. PMID: 25381486.

- Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, Martin S, Cahill AG, Odibo AO, et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing Skin Antiseptic Agents at Cesarean Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(7):647-55.

- Veiga DF, Damasceno CAV, Veiga-Filho J, Figueiras RG, Vieira RB, Florenzano FH, et al. Povidone iodine versus chlorhexidine in skin antisepsis before elective plastic surgery.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Xu PZ, Fowler JR, Goitz RJ. Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing the Efficacy of Surgical Preparation Solutions in Hand Surgery. Hand (N Y). 2017;12(3):258-64.

- Yeung LL, Grewal S, Bullock A, Lai HH, Brandes SB. A comparison of chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for eliminating skin flora before genitourinary prosthetic surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Urol. 2013;189(1):136-40.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

|

Study |

SSI / N total |

Treatment 1 |

Treatment 2 |

Type of surgery |

Wound class § |

ROB |

SSI definition |

|

Chlorhexidine-alcohol 0.5% vs Chlorhexidine-alcohol 2.0 - 2.5% (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.60 - 1.43) |

|||||||

|

Casey 2015 |

8 / 100 |

0.5% CHG in 70% IPA |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

Vascular surgery |

1 |

High |

CDC |

|

Chlorhexidine-alcohol 0.5% vs Aqueous iodine (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.47 - 1.02) |

|||||||

|

Srinivas 2015 |

50 / 351 |

0.5% CHG in 70% IPA |

5% PI (= 0.5% AI) |

Upper abdominal surgery |

2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Abreu 2014 |

10 / 56 ‡ |

0.5% CHG in alcohol |

0.5% PI (= 0.05% AI) |

Urological surgery |

1, 2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Brown 1984 |

58 / 737 ‡ |

0.5% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.75% AI |

General/mixed surgery |

1, 2, 3 |

Some concerns |

¶a |

|

Chlorhexidine-alcohol 0.5% vs Iodine-alcohol (RR 0.71; 95% CI 0.45 - 1.38) |

|||||||

|

Shadid 2019 |

0 / 59 |

0.5% CHG in 70% alcohol |

1% iodine in 70% alcohol |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Perek 2013 |

6 / 94 |

0.5% CHG in 70% ethanol |

PI in 50% propyl alcohol |

Cardiac surgery |

1 |

High |

CDC |

|

Cheng 2009 |

0 / 50 |

0.5% CHG with 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) in 23% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Veiga 2008 |

4 / 250 |

0.5% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) in alcohol |

Plastic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Chlorhexidine-alcohol 2.0 - 2.5% vs. Aqueous iodine (RR 0.75; 95% CI 0.61 - 0.92) |

|||||||

|

NIHR 2021 |

1163 / 5788 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

Abdominal surgery |

2, 3, 4 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Luwang 2020 |

21 / 311 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

Caesarean section |

1, 2 |

Some concerns |

¶b |

|

Danasekaran 2017 |

16 / 120 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

5% PI (= 0.5% AI) |

General surgery |

1, 2 |

Some concerns |

¶c |

|

Springel 2017 |

62 / 932 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.75% AI scrub + 10% PI paint (= 1% AI) |

Caesarean section |

1, 2 |

Low |

CDC |

|

Xu 2017-a* |

3 / 159 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

High |

¶d |

|

Bibi 2015 |

34 / 388 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

General surgery |

1, 2 |

High |

CDC |

|

Kunkle 2015 |

3 / 60 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

Caesarean section |

1, 2 |

High |

¶e |

|

Yeung 2013 |

5 / 100 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

7.5% iodine scrub + 10% PI paint (= 1% AI) |

Urological implant surgery |

2 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Darouiche 2010 |

110 / 897 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

General surgery |

2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Sistla 2010 |

33 / 556 |

2.5% CHG with 70% ethanol |

10% PI (= 1% AI) |

Inguinal hernia repair |

1 |

High |

CDC |

|

Saltzman 2009-a* |

0 / 100 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.75% iodine scrub + 10% PI paint (= 1% AI) |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Chlorhexidine-alcohol 2.0 - 2.5% vs. Iodine-alcohol (RR 0.77; 95% CI 0.60 - 1.00) |

|||||||

|

Ritter 2020 |

26 / 279 ‡ |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

1% PI (= 0.1% AI) in 70% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

High |

¶f |

|

Broach 2017 |

172 / 802 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.7% AI in 74.0% IPA |

Colorectal surgery |

2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Xu 2017-b* |

3 / 160 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.7% AI in 74.0% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

High |

¶d |

|

Tuuli 2016 |

84 / 1147 |

2% CHG with 70% IPA |

8.3% PI (= 0.83% AI) in 72.5% IPA |

Caesarean section |

1, 2 |

Low |

CDC |

|

Ngai 2015 |

60 / 1404 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.83% AI in 72.5% IPA |

Caesarean section |

2 |

Some concerns |

¶g |

|

Savage 2012 |

0 / 100 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.7% AI in 74.0% IPA |

Neurosurgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Saltzman 2009-b* |

0 / 100 |

2% CHG in 70% IPA |

0.7% iodophor in 74.0% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Chlorhexidine-alcohol 4.0% vs. Aqueous iodine (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.32- 1.41) |

|||||||

|

Gezer 2019 |

17 / 110 |

4.0% CHG with alcohol |

10% PI (=1% AI) |

Gynaecological surgery |

1, 2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Paocharoen 2009 |

13 / 500 |

4.0% CHG in 70% IPA |

10% PI (=1% AI) |

Not reported |

1, 2, 3 |

Some concerns |

¶h |

|

Bibbo 2005 |

0 / 127 |

4.0% CHG scrub + 70% IPA paint |

7.5% PI scrub + 10% PI paint (=1% AI) |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Aqueous chlorhexidine 4.0% vs. Aqueous iodine (RR 0.93; 95% CI 0.43 - 2.01) |

|||||||

|

Park 2017 |

31 / 534 |

4.0% soap + 2% paint CHG |

7.5% PI soap + 10% paint PI (=1% AI) |

Abdominal surgery |

2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Aqueous iodine vs Iodine-alcohol (RR 1.03; 95% CI 0.77 - 1.38) |

|||||||

|

Dior 2020 |

66 / 441 |

10% PI (=1% AI) |

1% iodine in 70% ethanol |

Gynaecological surgery |

1, 2 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Xu 2017-c* |

2 / 161 |

10% PI (=1% AI) |

0.7% iodine in 74.0% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

High |

¶d |

|

Saltzman 2009-c* |

0 / 100 |

0.75% iodine scrub + 1% iodine paint |

0.7% iodophor in 74.0% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

No definition |

|

Segal 2002 |

15 / 108 |

1% iodine |

0.7% AI in 74.0% IPA |

Cardiovascular surgery |

1 |

Some concerns |

CDC |

|

Howard 1991 |

15 / 240 |

iodophor scrub + solution |

iodophor in 70% IPA |

General surgery |

1, 2 |

Some concerns |

¶i |

|

Gilliam 1990 |

0 / 60 |

iodophor scrub + paint |

0.7% AI in 74.0% IPA |

Orthopaedic surgery |

1 |

Come concerns |

No definition |

|

Aqueous iodine vs Olanexidine 1.5% (RR 0.49; 95% CI 0.26 - 0.92) |

|||||||

|

Obara 2020 |

58 / 597 |

10% PI (=1% AI) |

1.5% aqueous olanexidine |

Gastro-intestinal surgery |

2 |

Come concerns |

CDC |

|

* Studies compare three skin preparation solutions ‡ Not all randomized patients, only per protocol numbers were available ¤ SSI secondary outcome, thus not adequately powered to detect SSI § 1: Clean, 2: Clean-contaminated, 3: Contaminated, 4: Dirty

SSI definitions, other than CDC: a: a minor wound infection was defined as an infected wound with superficial separation (less than 1 centimeter) involving less than one-third of the incision or induration of the wound edge believed by the surgeon to be secondary to infection; a major wound infection was defined. as an infected wound with separation of the wound edges greater than one-third of the length of the incision or frank wound infection with evidence of purulent exudate or abscess. b: purulent discharge from the incision site, wound dehiscence, localized pain or tenderness, localized swelling, and erythema or heat within 30 days following caesarean section c: for example; purulent/serous discharge from the wound, redness of the surrounding area, pain associated with discharge, increased local temperature, within 10 days of surgery d: need for antibiotics or surgical intervention, within 6 weeks of surgery e: presence of purulent drainage, cellulitis, or the need for incision and drainage, or treatment with antibiotics for a clinical diagnosis of infection, within two weeks of surgery f: wound healing disorders: when CDC criteria were met; SSI are diagnosed when CDC criteria plus one of the following criteria were met: 1) necessity of antibiotic therapy, 2) necessity of surgical intervention, 3) positive microbiological culture of swabs taken intraoperatively g: the patient reporting the requirement of antibiotic use for a wound infection or documented wound infection in the medical record at the outpatient visit within 30 days of discharge (according to Horan et al., and the CDC criteria) h: a surgical wound drained purulent material or if the surgeon judges it to be infected and opens it (incisional), within 1 month of surgery i: they drained pus, they developed significant, erythema at the margins of the wound (erythema around a suture "stitch abscess"-was not considered to be a wound infection), the wound drained serous fluid and was opened by the surgeon, or the wound was felt by the operating surgeon to be infected, within 30 days of surgery

IPA: isopropyl alcohol PI: povidone iodine AI: available iodine RR: Relative risk 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

PVP-I solutions used for disinfection of the skin or wounds have a 1% iodine68 |

|||||||

Risk of bias assessment

League tables and netranking

In the lower triangle of the league tables the network relative risks (RR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown. The upper triangle shows the relative risks of only the direct comparisons (comparable with a regular pairwise meta-analysis). For instance, in Appendix 4.a, the first column (in the lower triangle) shows the network RR with corresponding 95% CI of olanexidine 1.5% compared with the other skin antiseptics. The last column (upper triangle) shows the direct RR with corresponding 95% CI of aqueous iodine compared with the other skin antiseptics.

A. All wound classifications / any type of surgery

League table

|

Olanexidine 1.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.49 (0.26 - 0.92) |

|

0.73 (0.27 - 1.92) |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

|

|

|

|

0.67 (0.32 - 1.40) |

|

0.70 (0.33 - 1.48) |

0.97 (0.42 - 2.23) |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% |

3.00 (0.61 - 14.74) |

|

0.33 (0.08 - 1.44) |

0.68 (0.45 - 1.03) |

|

0.65 (0.33 - 1.27) |

0.90 (0.42 - 1.93) |

0.93 (0.60 - 1.43) |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% |

|

0.76 (0.57 - 1.03) |

0.77 (0.62 - 0.97) |

|

0.52 (0.15 - 1.42) |

0.72 (-.25 - 2.10) |

0.75 (0.31 - 1.78) |

0.80 (-.36 - 1.79) |

Aqueous CHG 4.0% |

|

0.93 (0.42 - 2.01) |

|

0.50 (0.25 - 1.01) |

0.69 (0.31 - 1.53) |

0.71 (0.45 - 1.14) |

0.77 (0.60 - 1.00) |

0.96 (0.42 - 2.19) |

Iodine-alcohol |

0.87 (0.54 - 1.40) |

|

0.49 (0.26 - 0.92) |

0.67 (0.32 - 1.40) |

0.69 (0.47 - 1.02) |

0.75 (0.61 - 0.92) |

0.93 (0.43 - 2.01) |

0.97 (0.73 - 1.29) |

Aqueous iodine |

Netranking P-score

Olanexidine 0.8866

CHG-alcohol 0.5% 0.6517

CHG-alcohol 4.0% 0.6345

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% 0.5891

Aqueous CHG 4.0% 0.3406

Iodine-alcohol 0.2257

Aqueous iodine 0.1719

B. Only wound classification I / clean surgery

League table

|

CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

|

|

|

0.36 (0.06 - 2.24) |

|

0.51 (0.05 - 5.04) |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% |

3.00 (0.51 - 17.53) |

0.32 (0.07 - 1.56) |

|

|

0.62 (0.09 - 4.38) |

1.21 (0.34 - 4.34) |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% |

0.51 (0.16 - 1.57) |

0.77 (0.36 - 1.68) |

|

0.34 (0.04 - 2.65) |

0.66 (0.19 - 2.30) |

0.55 (0.12 - 1.32) |

Iodine-alcohol |

0.51 (0.13 - 1.96) |

|

0.36 (0.06 - 2.24) |

0.71 (0.18 - 2.86) |

0.59 (0.29 - 1.20) |

1.07 (0.41 - 2.80) |

Aqueous iodine |

Netranking P-score

CHG-alcohol 4.0% 0.7787

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% 0.6928

CHG-alcohol 0.5% 0.5222

Iodine-alcohol 0.2705

Aqueous iodine 0.2355

C. Only wound classification I / clean surgery - clustering of CHG-alcohol

League table

|

CHG-alcohol |

0.42 (0.19 - 0.90) |

0.70 (0.41 - 1.18) |

|

0.54 (0.27 - 1.07) |

Iodine-alcohol |

3.00 (0.51 - 17.53) |

|

0.60 (0.36 - 0.99) |

1.11 (0.52 - 3.39) |

Aqueous iodine |

Netranking P-score

CHG-alcohol 0.9698

Iodine-alcohol 0.3138

Aqueous iodine 0.2164

D. Excluding studies investigating exclusively clean surgery

League table

|

Olanexidine 1.5% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.49 (0.27 - 0.88) |

|

0.73 (0.29 - 1.84) |

CHG-alcohol 4.0% |

|

|

|

|

0.67 (0.33 - 1.37) |

|

0.72 (0.35 - 1.46) |

0.99 (0.44 - 2.25) |

CHG-alcohol 0.5% |

|

|

|

0.68 (0.46 - 1.00) |

|

0.62 (0.33 - 1.15) |

0.85 (0.40 - 1.79) |

0.86 (0.56 - 1.33) |

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% |

|

0.81 (0.62 - 1.07) |

0.79 (0.64 - 0.97) |

|

0.52 (0.20 - 1.35) |

0.72 (0.26 - 2.02) |

0.73 (0.32 - 1.68) |

0.85 (0.40 - 1.81) |

Aqueous CHG 4.0% |

|

0.93 (0.44 - 1.94) |

|

0.50 (0.26 - 0.97) |

0.70 (0.32 - 1.50) |

0.70 (0.43 - 1.13) |

0.72 (0.64 - 1.04) |

0.96 (0.44 - 2.12) |

Iodine-alcohol |

0.95 (0.60 - 1.51) |

|

0.49 (0.27 - 0.88) |

0.67 (0.33 - 1.37) |

0.68 (0.46 - 1.00) |

0.79 (0.65 - 0.95) |

0.93 (0.44 - 1.94) |

0.97 (0.73 - 1.27) |

Aqueous iodine |

Netranking P-score

Olanexidine 0.8977

CHG-alcohol 0.5% 0.6825

CHG-alcohol 4.0% 0.6402

CHG-alcohol 2.0-2.5% 0.5434

Aqueous CHG 4.0% 0.3389

Iodine-alcohol 0.2322

Aqueous iodine 0.1615

Funnel plots

The comparison-adjusted funnel plot shows the effect estimate of a study (relative risks) versus its precision (standard error) for SSI. The funnel plot shows symmetry indicating that there are no differences between small and large studies in regards to the effect of the treatment (small-study effect). Comparison-adjusted funnel plot asymmetry can be caused by publication bias. Since we find no asymmetry (no small-study effect), publication bias is less likely.

Table of excluded studies

|

|

Author, Year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

1. |

Dorestan 20211 |

Outcome not of interest |

|

2. |

NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Gobal Surgery 20212 |

Study protocol |

|

3. |

Widmer 20213 |

Conference abstract |

|

4. |

Boisson 20194 |

Study protocol |

|

5. |

Charehbili 20195 |

No RCT |

|

6. |

Kesani 20196 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

7. |

Peel 20197 |

Quasi randomization (per day) |

|

8. |

Saha 20198 |

Conference abstract |

|

9. |

Takeuchi 20199 |

Study protocol |

|

10. |

Boisson 201910 |

Study protocol |

|

11. |

Dior 201811 |

Conference abstract |

|

12. |

Kesani 201812 |

Conference abstract |

|

13. |

Charles 201713 |

Setting outside of operating theatre |

|

14. |

Fahmi 201714 |

Conference abstract |

|

15. |

Springel 201715 |

Conference abstract |

|

16. |

Salama 201616 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

17 |

Stout 201617 |

Conference abstract |

|

18. |

Tuuli 201618 |

Conference abstract |

|

19. |

Ngai 201519 |

Conference abstract |

|

20. |

Peel 201420 |

Quasi randomization (per day) |

|

21. |

Rodrigues 201321 |

Quasi randomization (order of operation) |

|

22. |

Grewal 201222 |

Conference abstract |

|

23. |

Murray 201223 |

Conference abstract |

|

24. |

Nurs Stand. 2010 Mar 3;24(26):19 (No authors listed)24 |

Comment |

|

25. |

Moon 201025 |

Comment |

|

26. |

Ellenhorn 200626 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

27. |

Ostrander 200527 |

Quasi randomization (fixed order of treatments) |

|

28. |

Hort 200228 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

29. |

Meier 200129 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

30. |

Roberts 199530 |

Not retrievable |

|

31. |

Sharihatti 199331 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

32. |

Loukota 199132 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

33. |

Alexander 198533 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

34. |

Berry 198234 |

No standard intravenous surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis |

|

35. |

Polk 196735 |

Comparison not of interest |

|

||

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-12-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 01-12-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-12-2026

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules 2 tot 16 is in 2020 op initiatief van de NVvH een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor preventie van postoperatieve wondinfecties. Daarnaast is in 2022 op initiatief van het Samenwerkingsverband Richtlijnen Infectiepreventie (SRI) een separate multidisciplinaire werkgroep samengesteld voor de herziening van de WIP-richtlijn over postoperatieve wondinfecties: module 17-22. De ontwikkelde modules van beide werkgroepen zijn in deze richtlijn samengevoegd.

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoek financiering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Mevr. prof. dr. M.A. Boermeester |

Chirurg |

* Medisch Ethische Commissie, Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC * Antibiotica Commissie, Amsterdam UMC |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Hieronder staan de beroepsmatige relaties met bedrijfsleven vermeld waarbij eventuele financiële belangen via de AMC Research B.V. lopen, dus institutionele en geen persoonlijke gelden zijn: Skillslab instructeur en/of spreker (consultant) voor KCI/3M, Smith&Nephew, Johnson&Johnson, Gore, BD/Bard, TELABio, GDM, Medtronic, Molnlycke.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Institutionele grants van KCI/3M, Johnson&Johnson en New Compliance.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Ik maak me sterk voor een 100% evidence-based benadering van maken van aanbevelingen, volledig transparant en reproduceerbaar. Dat is mijn enige belang in deze, geen persoonlijk gewin.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Extra kritische commentaarronde. |

|

Dhr. dr. M.J. van der Laan |

Vaatchirurg |

Vice voorzitter Consortium Kwaliteit van Zorg NFU, onbetaald

|

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen.

|

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. W.C. van der Zwet |

Arts-microbioloog |

Lid Regionaal Coördinatie Team, Limburgs infectiepreventie & ABR Zorgnetwerk (onbetaald) |

||

|

Dhr. dr. D.R. Buis |

Neurochirurg |

Lid Hoofdredactieraad Tijdschrift voor Neurologie & Neurochirurgie - onbetaald |

||

|

Dhr. dr. J.H.M. Goosen |

Orthopaedisch Chirurg |

Inhoudelijke presentaties voor Smith&Nephew en Zimmer Biomet. Deze worden vergoed per uur. |

||

|

Mw. drs. H. Jalalzadeh |

Arts-onderzoeker |

Geen. |

Persoonlijke financiële belangen Geen.

Persoonlijke relaties Geen.

Extern gefinancierd onderzoek Geen.

Intellectuele belangen en reputatie Geen.

Overige belangen Geen. |

Geen.

|

|

Dhr. dr. N. Wolfhagen |

AIOS chirurgie |

|||

|

Mw. drs. H. Groenen |

Arts-onderzoeker |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. F.F.A. Ijpma |

Traumachirurg |

|||

|

Dhr. dr. P. Segers |

Cardiothoracaal chirurg |

|||

|

Mw. Y.E.M. Dreissen |

AIOS neurochirurgie |

|||

|

Dhr. R.R. Schaad |

Anesthesioloog |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland voor de invitational conference. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodules zijn tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt. Voor de modules 17-22 was de patiëntfederatie vertegenwoordigd in de werkgroep.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn.

Voor module 8 (Negatieve druktherapie) geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000 - 40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Voor de overige modules en aanbevelingen geldt dat uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten). Tevens volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet en het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Ook wordt geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners verwacht of een wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

Zie voor de implementatie het implementatieplan in het tabblad 'Bijlagen'.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroepen de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten die chirurgie ondergaan. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door middel van een invitational conference. De verslagen hiervan zijn opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Adaptatie

Een aantal modules van deze richtlijn betreft een adaptatie van modules van de World Health Organization (WHO)-richtlijn ‘Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection’ (WHO, 2018), te weten:

- Module Normothermie

- Module Immunosuppressive middelen

- Module Glykemische controle

- Module Antimicrobiële afdichtingsmiddelen

- Module Wondbeschermers bij laparotomie

- Module Preoperatief douchen

- Module Preoperatief verwijderen van haar

- Module Chirurgische handschoenen: Vervangen en type handschoenen

- Module Afdekmaterialen en operatiejassen

Methode

- Uitgangsvragen zijn opgesteld in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- De inleiding van iedere module betreft een korte uiteenzetting van het knelpunt, waarbij eventuele onduidelijkheid en praktijkvariatie voor de Nederlandse setting wordt beschreven.

- Het literatuuronderzoek is overgenomen uit de WHO-richtlijn. Afhankelijk van de beoordeling van de actualiteit van de richtlijn is een update van het literatuuronderzoek uitgevoerd.

- De samenvatting van de literatuur is overgenomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij door de werkgroep onderscheid is gemaakt tussen ‘cruciale’ en ‘belangrijke’ uitkomsten. Daarnaast zijn door de werkgroep grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming gedefinieerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten, en is de interpretatie van de bevindingen primair gebaseerd op klinische relevantie van het gevonden effect, niet op statistische significantie. In de meta-analyses zijn naast odds-ratio’s ook relatief risico’s en risicoverschillen gerapporteerd.

- De beoordeling van de mate van bewijskracht is overgnomen van de WHO-richtlijn, waarbij de beoordeling is gecontroleerd op consistentie met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (GRADE-methode; http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). Eventueel door de WHO gerapporteerde bewijskracht voor observationele studies is niet overgenomen indien ook gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies beschikbaar waren.

- De conclusies van de literatuuranalyse zijn geformuleerd in overeenstemming met de standaardprocedures van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

- In de overwegingen heeft de werkgroep voor iedere aanbeveling het bewijs waarop de aanbeveling is gebaseerd en de aanvaardbaarheid en toepasbaarheid van de aanbeveling voor de Nederlandse klinische praktijk beoordeeld. Op basis van deze beoordeling is door de werkgroep besloten welke aanbevelingen ongewijzigd zijn overgenomen, welke aanbevelingen niet zijn overgenomen, en welke aanbevelingen (mits in overeenstemming met het bewijs) zijn aangepast naar de Nederlandse context. ‘De novo’ aanbevelingen zijn gedaan in situaties waarin de werkgroep van mening was dat een aanbeveling nodig was, maar deze niet als zodanig in de WHO-richtlijn was opgenomen. Voor elke aanbeveling is vermeld hoe deze tot stand is gekomen, te weten: ‘WHO’, ‘aangepast van WHO’ of ‘de novo’.

Voor een verdere toelichting op de procedure van adapteren wordt verwezen naar de Bijlage Adapteren.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.