Behandeling met lasercoagulatie versus anti-VEGF

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van intravitreale injectie met bevacizumab of ranibizumab bij ROP behandeling?

Aanbeveling

Behandel type 1 ROP/A-ROP in Zone I bij voorkeur primair met anti-VEGF.

Overweeg behandeling met anti-VEGF, in plaats van laser, bij type 1 ROP in posterieure Zone II, met name wanneer er sprake is van A-ROP, ROP die zeer vroeg ontwikkelt (<35 weken PMA) of wanneer de conditie van de patiënt een laserbehandeling onder narcose niet toelaat.

Behandel met laser wanneer er sprake is van type 1 ROP in Zone II.

Gebruik voor behandeling met anti-VEGF een voor de doelgroep geregistreerd middel en gebruik de daarvoor ontwikkelde toedieningsmethodiek.

Behandel niet met een intra-oculaire injectie als er sprake is van een ooginfectie.

Controleer na laserbehandeling binnen 7-10 dagen, daarna afhankelijk van respons iedere 1-3 weken tot ROP in remissie is. Plan 6 maanden na de laatste ROP screening een oogheelkundige controle (zie Stroomschema).

Controleer na anti-VEGF behandeling binnen 24-48 uur op tekenen van endophthalmitis, binnen 3-5 dagen het effect op ROP stadium en daarna wekelijks in de eerste maand en, in afbouwende frequentie, elke 2-12 weken gedurende 2 jaar of tot laserbehandeling verricht is, of tot volledige vascularisatie van de retina over 360˚ gerealiseerd is (zie Stroomschema).

Laat behandeling met laser of anti-VEGF uitvoeren in een centrum met oogheelkundige, neonatologische en anesthesiologische ervaring bij prematuur geborenen en prematurenretinopathie.

Stuur kinderen met een indicatie voor vitrectomie (stadium 4 of 5) en kinderen die progressie van ROP laten zien ondanks primaire behandeling door naar een centrum dat ervaring heeft met vitrectomie bij prematuur geborenen.

Zie ook het Stroomschema.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat regressie is er met redelijke zekerheid te concluderen dat er geen verschil is tussen intravitreale injecties en behandeling met laser. Voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat netvliesloslating is er met lage zekerheid te concluderen dat intravitreale injecties in het voordeel zijn ten opzichte van laserbehandeling. Ten opzichte van laserbehandeling is de kans dat er herbehandeling nodig is groter na intravitreale injectie vanwege onvoldoende reactie of reactivatie. De bewijskracht hiervoor is redelijk. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten is laag, dit komt vooral omdat er studies zijn gedaan met lage patiëntaantallen en met een risico op bias.

Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat cataract lijkt er geen verschil te zijn tussen de twee behandelmodaliteiten. De bewijskracht hiervoor is laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaat myopie lijken intravitreale injecties in het voordeel te zijn, de bewijskracht hiervoor is laag. Voor de belangrijke uitkomstmaten maculaplooi- of tractie, endophthalmitis en visus de bewijskracht te laag om richting te geven aan de conclusie.

Normale uitgroei van retinale vaten start in de 16e week van de zwangerschap. Hierbij spelen twee processen een rol: vasculogenese en angiogenese. Tijdens vasculogenese worden de vier retinale vaatarcades gevormd. Dit proces vindt plaats in de oppervlakkige lagen van de retina en is onafhankelijk van VEGF productie. Tijdens de angiogenese groeien arteriën en venen vanuit de, tijdens vasculogenese aangelegde, grote vaten naar de ora serrata en richting de macula. Dit proces vindt plaats vanuit de oppervlakkige plexus naar de diepere lagen van de retina, is voltooid rond de à terme datum en wordt geactiveerd door de aanwezigheid van onder andere VEGF. De vaten gevormd door vasculogenese bevinden zich met name in Zone I. Het feit dat met laser de productie van VEGF geremd wordt door uitschakelen van perifere avasculaire retina zou vanuit pathofysiologisch oogpunt kunnen verklaren waarom ROP in Zone I minder goed reageert op behandeling met laser.

Als behandelcriterium wordt de ETROP-classificatie gehanteerd. Dit betekent dat Type 1 ROP een behandelindicatie is en Type 2 ROP nauwkeurig en frequent gecontroleerd moet worden. Ook agressieve (A)-ROP is een behandelindicatie. A-ROP kan in elke zone voorkomen en kenmerkt zich door snelle progressie, ernstige plus disease die niet in verhouding is met de perifere veranderingen en arterioveneuze shunts of circulair verlopende vaten. Binnen de groep van kinderen met ROP met een behandelindicatie is het zinvol onderscheid te maken tussen ROP dat het behandelstadium bereikt in zone I versus zone II.

Bij de subgroep analyse, in de bekeken RCT’s, van ogen met zone I ROP wordt zowel bij behandeling met intravitreale injecties als bij laser een duidelijk grotere kans op herbehandeling geconstateerd (ongeveer 30%) in vergelijking met ogen die behandelstadium in zone II bereiken.

Uit subgroep analyse, in de bekeken RCT’s, van ogen met zone II ROP kan geconcludeerd worden dat de kans op herbehandeling na primaire laser laag is (ongeveer 5%), ten opzichte van anti-VEGF behandeling (ongeveer 15%). Dit is in overeenstemming met de ervaring van de werkgroep dat een laser bij ROP in zone II in grote meerderheid der gevallen een definitieve behandeling betreft, waarbij regressie van ROP binnen 2-3 weken gezien wordt, het resultaat afdoende en blijvend is en er daardoor geen noodzaak bestaat tot zeer lange en frequente follow-up van deze patiënten, hetgeen wel het geval zou zijn bij anti-VEGF therapie in deze groep.

Intra-oculaire behandeling met anti-VEGF leidt tot systemische absorptie waardoor verlaagde waarden voor VEGF in serum gevonden kunnen worden. VEGF is een belangrijke factor voor angiogenese en ontwikkeling van verschillende organen. In Europa is voor de indicatie ROP bevacizumab off-label gebruik, ranibizumab sinds 2020 geregistreerd (met bijbehorend doseringsapparaat voor neonatale dosis) en aflibercept naar verwachting geregistreerd in 2023 (met bijbehorend doseringsapparaat voor neonatale dosis) (Furuncuoglu, 2022; Huang, 2017; Stahl, 2022). Studies laten zien dat systemische suppressie in het geval van ranibizumab niet of kort (1-2 weken) meetbaar is (Stahl, 2019), in het geval van bevacizumab en aflibercept (Stahl, 2022) is de suppressie tot minstens 8 weken meetbaar (Furuncuoglu, 2022; Huang, 2018).

Over de langere termijn gevolgen van het toedienen van intra-oculair anti-VEGF op de overige ontwikkeling van een kind is nog te weinig bekend om conclusies te trekken of een risicoschatting te maken. De resultaten van studies variëren sterk en de follow up is relatief kort (meeste studies <2 jaar, langste follow up 5 jaar) om effecten op neurologische ontwikkeling te meten. (Fan 2019). De onbekendheid hiervan is vooralsnog een argument ten nadele van anti-VEGF behandeling.

Overwegingen over behandelrespons en herbehandeling

Een goede reactie op behandeling betekent dat neovascularisaties, tekenen van plus disease en ROP stadium (op overgang gevasculariseerd naar ongevasculariseerd gebied) afnemen. De eerste effecten van behandeling, afname van plus disease, zijn na laser meestal binnen 10 dagen zichtbaar. Na behandeling met anti-VEGF is dit effect sneller zichtbaar, in de meerderheid van de gevallen binnen 5 dagen na toediening. (Stahl 2019, Mintz-Hittner, 2016, Lepore 2018).

Na een primaire laserhandeling, die onvoldoende effect heeft is er doorgaans sprake van zogenaamde ‘skipped areas’ – gebieden waar geen of onvoldoende effect bereikt is. Hier zal, na identificeren van deze skip laesies (met ophthalmoscopie met indentatie of digitale beeldvorming), aanvullende behandeling met laser de eerste keus zijn. Zeer zelden wordt secundair anti-VEGF behandeling toegepast. Toediening binnen 4 weken na laser wordt sterk afgeraden omdat enerzijds laser de bloed-retina barrière doorbreekt hetgeen leidt tot hogere systemische VEGF concentraties, en anderzijds een fibrotische reactie in het oog in gang kan zetten die na de toediening van anti-VEGF kan leiden tot het ‘crunch’ syndroom, een progressieve ablatio retinae die binnen 3 dagen tot een stadium 5 leidt (Yonekawa 2018).

Indien na primaire behandeling met anti-VEGF geen duidelijke afname van plus tekenen binnen 5 dagen gezien wordt, moet gedacht worden aan een probleem met de toediening of onder-dosering van de anti-VEGF en in deze situatie kan gekozen worden voor een tweede behandeling met anti-VEGF. Indien geen twijfel bestaat over toediening en dosering, kan voor een ‘rescue’ laserbehandeling gekozen worden.

Meerdere studies hebben aangetoond dat een lange termijn consequentie van behandeling met anti-VEGF is dat de vaatuitgroei in grote gebieden van de perifere retina onvoldoende is, met name bij ROP in Zone I (Lepore, 2018; Mintz-Hittner, 2011; Moran, 2014). Achterblijvende angiogenese door het inhiberende effect van anti-VEGF leidt tot onvolledige vascularisatie van de perifere retina en onderontwikkelde capillairen. Vier jaar na behandeling vond Lepore uitgebreide avasculaire gebieden met afwezigheid van capillair vaatbed na behandeling met bevacizumab bij 91.6%, ranibizumab bij 75% en laser bij 10.5%. Lekkage bij de overgang van gevasculariseerde naar ongevasculariseerde retina werd gezien bij 65% van de ogen die behandeld waren met bevacizumab, terwijl de met laser behandelde ogen chorioretinale atrofie toonden (Chow, 2022).

Bij behandeling van ROP met anti-VEGF bestaat dus een grote kans op re-activatie en noodzaak tot herbehandeling. Deze re-activatie van ROP treedt later op, meestal 6-14 weken na de primaire behandeling, maar is ook nog beschreven 2 jaar na behandeling (Stahl 2019, Mintz-Hittner 2016, Lepore 2018). Dit betekent dat kinderen die primaire anti-VEGF behandeling krijgen langdurige, frequente, belastende controle nodig hebben en dat de ouders een lange periode in onzekerheid verkeren over de afloop.

Om die reden is, in geval van reactivatie van ROP na succesvolle primaire behandeling met anti-VEGF, laser de eerste keus voor herbehandeling. Daarnaast lijkt na primaire behandeling met anti-VEGF ook bij voldoende reactie en geen duidelijke reactivatie van ROP (stadium- of plus ziekte), maar persisterende perifere avasculariteit, laserbehandeling van de perifere retina in tweede instantie (zgn. ‘deferred laser’) een goede optie om lange termijn effecten van blijvende ischaemie en zeer late recidiefkans weg te nemen.

Vooralsnog wordt de behandelstrategie van ‘deferred laser’ vooral op grond van expert opinion en op kleinere case series in de literatuur gebaseerd (Moshfeghi 2019). Het optimale moment van de secundaire laser hangt van verschillende factoren af, namelijk de omvang van de nog avasculaire zone of onderontwikkeling van capillaire vaatbed (alleen aan te tonen met FAG) en de halfwaardetijd van het gegeven medicijn.

Samenvattend kan gesteld worden dat er niet één perfecte behandeling voor ROP bestaat, maar dat vele factoren een rol spelen bij de uiteindelijke keuze. In deze nieuwe richtlijn wordt meer vormgegeven aan de plaats van anti-VEGF bij de behandeling van ROP. Reden om argumenten voor en tegen behandeling met anti-VEGF in Zone I op een rij te zetten:

Argumenten voor anti-VEGF behandeling

- De behandeling is korter en minder complex dan laserbehandeling waardoor narcose niet noodzakelijk is;

- Kinderen met ROP in zone 1 hebben een grote avasculaire zone waardoor hoge concentraties VEGF kunnen leiden tot snel progressieve ROP. Voordeel van anti-VEGF in deze situatie is dat de behandelrespons van anti-VEGF sneller is (<5 dagen) t.o.v. laserbehandeling (<10 dagen);

- Op pathofysiologische gronden is ROP in zone I mogelijk minder responsief op laserbehandeling;

Argumenten tegen anti-VEGF behandeling

- Het betreft een intra-oculaire behandeling met bijkomend infectierisico en een actieve oog- of ooglidinfectie is hierom een contraindicatie voor deze behandeling;

- Er is nog veel niet bekend over dosering, timing en lange termijn systemische effecten van behandeling. In Nederland is de ervaring beperkt;

- Vergevorderde ROP met fibrotische veranderingen van de retina ter plaatse van de wal zijn een contra-indicatie voor behandeling met anti-VEGF vanwege de kans op snel ontwikkelende tractie ablatio;

- Persisterende avasculaire retina na primaire anti-VEGF behandeling geeft grote kans reactivatie, in tegenstelling tot een correct uitgevoerde laserbehandeling. Deze reactivatie treedt vooral op in de eerste 14 weken na behandeling, maar kan voorkomen tot 2 jaar na behandeling. Dit vergt langdurig, frequente controle, hetgeen niet nodig is na laserbehandeling;

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De belangrijkste doelen voor interventie bij ROP voor de patiënt en ouder(s)/verzorger(s) is voorkomen van slechte uitkomsten (netvliesloslating) en ernstige slechtziendheid of blindheid (natuurlijk beloop van ernstige ROP) en tegelijkertijd een zo minimaal mogelijke belasting voor de neonaat (aantallen controles, behandelingen en narcose/sedatie).

De noodzaak tot veel controles gedurende een lange periode (belasting neonaat en ouders), langdurige onzekerheid over de uitkomst (belasting ouders) en de hogere kans op herbehandeling is een nadeel van anti-VEGF behandeling en dient meegewogen te worden bij het besluit om primair met anti-VEGF te behandelen. Omdat kinderen in de subgroep met Zone I ROP een groot, te behandelen, avasculair gebied en meer en ernstiger co-morbiditeit hebben, weegt het risico van een langere narcose (belasting neonaat) relatief zwaarder. Omdat ook de effectiviteit van laser bij behandeling in Zone I mogelijk minder is, moet dit meegewogen worden bij het maken van een keuze voor primaire behandeling in Zone I. In de overweging kan de optie om eerst met anti-VEGF en in tweede instantie aanvullend met laser te behandelen meegenomen worden. Alle voor- en nadelen die voor de ouders van belang zijn om een goede afweging te maken, dienen duidelijk met hen besproken te worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Een laserbehandeling brengt aanvankelijk hoge kosten met zich mee, vanwege de noodzaak voor narcose, beschikbaarheid van laserapparatuur, eventueel transport naar een behandelcentrum, de langere behandelduur en NICU bed voor nabeademing (Trzcionkowska, 2022). De kosten van anti-VEGF behandeling worden primair bepaald door de kosten van het geneesmiddel. Op het moment van verschijnen van deze richtlijn zijn ranibizumab en aflibercept geregistreerd voor de behandeling van ROP en is bevacizumab alleen off-label beschikbaar., Ondanks de hogere kosten is de werkgroep van mening dat het, bij deze kwetsbare groep, de voorkeur heeft te behandelen met geregistreerde middelen. Daarnaast is vastgesteld dat de systemische resorptie van ranibizumab korter is dan van bevacizumab. De meer frequente controles over een lange periode en de noodzaak tot herbehandeling bij de anti-VEGF behandeling zullen op de lange termijn leiden tot hogere kosten.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Wanneer een groter deel van de ROP patiënten behandeld gaat worden met anti-VEGF zal dit naar verwachting leiden tot een hogere belasting van het zorgsysteem (meer screeningen) vanwege de hoge controle frequentie over een lange periode en het aantal herbehandelingen. In de studie van Trzcionkowska (2021) wordt een toename van ROP behandelingen in Nederland geconstateerd. Een onderzoek naar de impact op de zorg en de haalbaarheid in de toekomst is nog niet verricht.

De onbekendheid van lange termijn oogheelkundige en systemische bijwerkingen in het geval van anti-VEGF behandeling is een vaak aangehaald argument van collega’s en ook ouders van de patiënt. Daarom is altijd een zorgvuldige afweging nodig en kan gezamenlijke besluitvorming na goede voorlichting helpen.

In Nederland is toegankelijkheid voor zorg (waaronder ook ROP zorg), wanneer de patiënt nog is opgenomen op de neonatale units (intensive care, medium care) en kinderafdelingen, in het algemeen goed. Bij langdurige follow-up na de periode van opname kan toegang tot deze zorg in sommige bevolkingslagen moeizamer zijn door bijvoorbeeld reisafstand, vervoerkosten, zorgverzekering en/of taalbarrière. Dit vormt een risico bij anti-VEGF behandeling vanwege het grote belang van frequente controles over een lange periode, tot ver na de klinische opname van de patiënt. Indien er een groot risico voor reactivatie van ROP en uit controle raken van patiënt wordt ingeschat, kan nog sterker overwogen worden secundaire laser na primair anti-VEGF op een gepland moment te verrichten en niet op reactivatie te wachten.

Belemmeringen voor laser

- Beschikbaarheid en ervaring behandelaar met laser (opleiding/training/routine);

- Beschikbaarheid laserapparatuur;

- Noodzakelijkheid narcose, kinderanesthesioloog;

- OK duur.

Belemmeringen voor anti-VEGF

- Beschikbaarheid medicatie;

- Toedieningsmateriaal;

- Intraoculaire behandeling met bijkomend infectierisico;

- Ervaring oogarts met besluitvorming rond indicatie (timing, dosering);

- Ervaring oogarts intravitreale injectie bij prematuur (technische handeling).

Beschikbaarheid van OK-tijd op korte termijn (<1 week, spoed) en aanwezigheid van een kinderanesthesioloog is een voorwaarde bij laserbehandeling wat in veel ziekenhuizen niet altijd realiseerbaar is. Beschikbaar maken van medicatie in dosering en toedieningsmechanisme voor het premature oog is in de meeste ziekenhuizen in Nederland haalbaar. Beschikbaarheid van een behandelaar met ervaring met laserbehandeling bij prematurenretinopathie is een beperkende voorwaarde voor de laserbehandeling; in Nederland zijn slechts een aantal centra met voldoende ervaring voor deze behandeling. In theorie zou (mits getraind voor toediening bij prematuren) iedere oogarts de technische handeling uit kunnen voeren om een intravitreale injectie bij de neonaat toe te dienen. Vanwege de complexe indicatiestelling en timing van anti-VEGF behandeling bij ROP, is in Nederland sinds 2020 in een beperkt aantal behandelcentra ervaring opgedaan hiermee. Wanneer in de toekomst nieuwe centra anti-VEGF injecties toe gaan dienen, dan is een vereiste dat een camera aanwezig is om 1) indicatie af te stemmen met een ander centrum met ervaring in indicatiestelling en 2) een goede follow up te kunnen doen en de resultaten te evalueren. Een FAG modaliteit bij de camera kan ondersteuning bieden bij het bepalen van de vascularisatie van de perifere retina. Deze module is kostbaar en het aantal kinderen waarvoor dit toegevoegde waarde zou hebben klein.

Overwegingen omtrent diode versus argon laser

In de meeste landen en centra wordt laserbehandeling bij ROP succesvol uitgevoerd met een diode laser (810 nm). De laatste jaren wordt ook veel behandeld met groene argon laser (532 nm). Er bestaat geen gerandomiseerd vergelijkend onderzoek tussen deze twee laser modaliteiten bij ROP. Vanwege diepere weefselpenetratie/verbranding bij de diode laser t.o.v. de argon laser is er meer intraoculaire inflammatie, met name bij een groot aantal laserspots. Dat diode laser meer inflammatie in choroideaweefsel veroorzaakt werd bevestigd in diermodellen (Benner, 1992). Deze inflammatie (in combinatie met andere mechanismen waaronder verbreken bloed-retina barrière, veneuze stase en vasoactieve reactie) kan op korte termijn na de laserbehandeling de kans op een exsudatieve ablatio verhogen. De meeste gevallen van exsudatieve ablatio na laserbehandeling bij ROP in de literatuur zijn geassocieerd met diodelaser (Dikci, 2020). Daarnaast kan in de fase na inflammatie fibrose ontstaan, hetgeen op langere termijn (theoretisch) de kans op tractie ablatio en temporaal verplaatsing van de macula verhogen.

Behandeling met de diode laser t.o.v. de argonlaser wordt gezien als technisch moeilijker vanwege wisselend effect van coagulaten, waardoor het risico op onder- (skip area’s) of overbehandeling groter wordt. In de beschikbare literatuur werd geen verschil gevonden in het risico op voorsegment complicaties na laser, te weten cataract, voorsegmentischaemie, hyphaem en cornea/iris verbranding tussen diodelaser en argonlaser (Dikci, 2020).

De werkgroep beveelt aan om de laserbehandeling bij ROP bij voorkeur met een groene argonlaser (532nm) te verrichten vanwege de theoretische en in retrospectief onderzoek onderbouwde verhoogde kans op achtersegment complicaties bij gebruik van de diodelaser.

Overwegingen omtrent centralisatie van behandeling

In Nederland zijn een beperkt aantal centra met voldoende ervaring en beschikbaarheid van apparatuur om ROP behandeling te kunnen verrichten. Vanwege de kleine groep patiënten die op jaarbasis in aanmerking komt voor behandeling, de complexiteit van behandeling en grote consequenties van suboptimale behandeling (Spandau, 2014; Holmström, 2016) is de werkgroep van mening dat het belangrijk is deze zorg te concentreren in de bestaande centra, om voldoende ingrepen per behandelaar (afhankelijk van ervaring) te waarborgen. Concentratie van deze zorg zal leiden tot overplaatsingen van meestal kwetsbare/hoog-risico patiënten tussen ziekenhuizen, maar in de meerderheid der gevallen weegt dit risico op tegen het garanderen van de kwaliteit van de ROP behandeling. In de zeldzame gevallen dat overplaatsingsrisico te groot wordt geacht binnen een acceptabele behandeltermijn, is een goede oplossing een behandelaar (inclusief apparatuur) naar de patiënt te detacheren.

Verder is de werkgroep van mening dat opleiding door een ervaren oogarts in ROP behandelingen in een centrum met voldoende behandelindicaties noodzakelijk is om op verantwoorde wijze te kunnen starten met deze behandelingen. Belangrijk is ook dat een behandelcentrum beschikbaarheid van een behandelaar zo veel mogelijk waarborgt.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Studies naar de resultaten van laser- en anti-VEGF behandeling laten zien dat anti-VEGF de primaire behandeling van eerste keus is bij de behandeling van ROP in Zone I. Voor de behandeling van ROP in zone II heeft laserbehandeling de voorkeur. Over de primaire keuze van behandeling bij type 1 ROP in posterieure zone II is geen sluitend bewijs. De kans op herbehandeling bij patiënten met ROP in zone II (merendeel van ROP patiënten in Nederland) is kleiner na laser- dan na anti-VEGF behandeling. Na anti-VEGF behandeling is frequente follow-up, zelfs tot 2 jaar na injectie, noodzakelijk vanwege de kans op recidief waardoor langdurig onzekerheid over het eindresultaat van de behandeling blijft bestaan, tenzij een laserbehandeling van de nog niet gevasculariseerde retina alsnog verricht wordt op een later moment ten tijde van reactivatie of (in geval van geen reactivatie) op een gepland moment. Dit weegt zwaar bij de aanbevelingen die de werkgroep formuleert over de voorkeuren voor behandeling. Bij de keuze weegt verder mee dat de andere twee cruciale uitkomstmaten regressiekans en netvliesloslating en het risico op complicaties (endophthalmitis, cataract, maculaplooi) geen klinisch relevant verschil laten zien bij de twee behandelmodaliteiten. De kans op hoge myopie is groter na laserbehandeling, maar dit effect lijkt het grootst te zijn bij de subgroep van zeer jonge (<35 weken) en zone I ROP patiënten, bij wie primair anti-VEGF eerste keus is. Zie ook het Stroomschema.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het merendeel van de ROP-patiënten die aan de behandelcriteria (Type 1) van de Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity (ETROP) studie voldoen, wordt in Nederland de laatste jaren behandeld met lasercoagulatie. Met deze behandeling wordt een netvliesloslating in meer dan 90% der gevallen voorkomen (Trzcionkowska, 2021). Deze hoge succeskans kan verklaard worden door relatief vroege behandeling, namelijk het includeren van ROP 2 in zone II met progressieve plus tekenen als indicatie voor behandeling. Dit behandelcriterium is in sommige landen omstreden en ook in enkele grotere studies wordt pas bij ROP 3 in zone II behandeld. In internationale studies worden succespercentages na één laserbehandeling rond de 85% beschreven (Popovic, 2021).

Lasercoagulatie betreft meestal een eenmalige behandeling en het beloop na de behandeling is redelijk voorspelbaar. Er zijn bekende korte- of lange-termijn effecten van laserbehandeling bij ROP, zoals myopie, netvliesafwijkingen zoals temporaal verplaatsen van de macula of netvlies plooien, cataract en voorsegment ischemie. Tractie, bijvoorbeeld door een retinaplooi, kan leiden tot (partiële) ablatio retinae. De behandeling met laser is complex in uitvoering en resultaten zijn bewezen slechter in geval van minder ervaring bij de behandelaar (Spandau, 2020, Holmström 2016). Resultaten van laser in het algemeen zijn minder voorspelbaar en minder succesvol bij zeer jonge ROP-patiënten (<35 weken op moment van behandeling), zeer posterieur gelokaliseerde ROP (zone I) en Agressieve (A)-ROP. Bovendien is narcose noodzakelijk om laser te kunnen uitvoeren, met bijkomende risico’s.

Anti-VEGF bij ROP-patiënten heeft mogelijk een voordeel omdat er geen narcose noodzakelijk is, de duur van behandeling kort is en er doorgaans snel een afname van ROP activiteit optreedt. Daarnaast heeft anti-VEGF behandeling een ander (maar nog onvolledig bekend) lange termijn bijwerkingen profiel dan laser. Een wel al bekend, belangrijke lange termijn consequentie van anti-VEGF behandeling is blijvende ischemie van de perifere retina door onvolledige uitgroei van retinale vaten en onvoldoende ontwikkeling van het capillaire vaatbed. Daarbij is de werkingsduur van toegediende anti-VEGF beperkt. Dit kan aanleiding zijn voor re-activatie van ROP meestal binnen 3 maanden maar ook beschreven tot 2 jaar na primaire behandeling (Mintz-Hittner 2016, Lepore 2018). Daardoor zal de termijn van follow up, in vergelijking met laserbehandeling, langer zijn en de kans op herbehandeling groter.

Conclusies

Regression (critical)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Intravitreal injection likely results in little to no difference in regression rate when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Popovic, 2021: Karkhaneh, 2016; Mintz-Hittner, 2011 (BEAT-ROP study); Roohipor, 2019; Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) and Zhang, 2017 |

Retinal detachment (critical)

|

Low GRADE |

Intravitreal injection may reduce retinal detachments when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Popovic, 2021 (Harder, 2013; Hwang, 2015; Kabatas, 2017; Lepore, 2018; Lolas, 2017; Mintz-Hittner, 2011; Mueller, 2017; Stahl, 2019 and Gunay, 2017), Barry, 2019; Ling, 2020 and Murakami, 2021 |

Additional treatment (critical)

|

Moderate GRADE |

Intravitreal injection likely increases the likelihood of additional treatment when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Popovic, 2021 (Karkhaneh, 2016; Moran, 2014; Roohipor, 2019; Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) and Zhang, 2017) |

Retinal dragging / retinal fold (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an intravitreal injection on retinal dragging / retinal folds when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Adams, 2019; Mueller, 2017; Roohipoor, 2019 and Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) |

Cataract (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Intravitreal injections may not reduce or increase cataract when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Mintz-Hittner, 2011; Roohipor, 2019 and Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) |

Endophthalmitis (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an intravitral injection on endophthalmitis in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) |

Myopia (important)

|

Low GRADE |

Intravitreal injection may reduce development of myopia when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Popovic 2021 (Geloneck, 2014) and Lepore, 2020 |

Visual acuity (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of an intravitreal injection on visual acuity when compared with laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity.

Sources: Lepore, 2020 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Systematic reviews

Popovic (2021) is a systematic review, including risk of bias assessment and meta-analysis in which any prospective or retrospective comparative study reporting on the efficacy and/or safety of ophthalmologic data following intravitreal injections and laser photocoagulation in patients with retinopathy of prematurity was included. Articles without relevant efficacy and/or safety data for both intravitreal injection and laser photocoagulation study arms were excluded. A systematic search was performed from January 2005 to December 2019. This systematic review included eight RCTs (Geloneck, 2014; Karkhaneh, 2016; Lepore, 2018; Mintz-Hittner, 2011 (BEAT-ROP study); Moran, 2014; Roohipor, 2019; Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study); Zhang, 2017) and 5 observational studies (Adams, 2018; Gunay, 2017; Hwang, 2015; Kabatas, 2017; Lolas, 2017;) that reported outcome measures relevant for this analysis. All RCTs randomized participants to the intervention or control group, except for Lepore (2018) and Moran (2014) in which one eye received anti-VEGF and the fellow eye underwent laser treatment. Included participants were diagnosed with Type I ROP, except for Gunay (2017) which included patients diagnosed with aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity (APROP) and Mintz-Hittner (2011), which included Threshold ROP. Participants were born between 24- and 29-weeks postmenstrual age. Intra-vitreal injections included bevacizumab with a minimum dosage of 0.25 mg (Lepore, 2018) to a maximum dosage of 1.25mg (Moran, 2014) or ranibizumab with a minimum of 0.1 mg (Stahl, 2019) to a maximum of 0.3 mg (Zhang, 2019). The control groups underwent laser photocoagulation (see Evidence table). The relevant outcome measures for this analysis were: regression rate, retinal detachment, likelihood of additional treatment, retinal fold, cataract, (description of) endophthalmitis, myopia (spherical equivalent) and uncorrected visual acuity. Follow-up period was at least 4.5 month, up to 2.5 years. Authors of the review reported conflicts of interest (see Evidence table). There was no funding source for this study.

Wang (2020) is a systematic review which included RCTs and retrospective studies that compared intravitreal injections monotherapy of ranibizumab or bevacizumab with laser therapy in retinopathy of prematurity. Studies whose patients were diagnosed as neither type-1 ROP nor APROP were excluded. A systematic search was performed from 1980 to December 7, 2018. The review included four observational studies additional to Popovic (2021): Harder (2013), Kuo (2015), Mueller (2017) and Spandau (2013) that reported outcome measures relevant for this analysis. Anti-VEGF included bevacizumab 0.375 mg or 0.625 mg and the control groups underwent laser photocoagulation (see Evidence table). The relevant outcome measures for this analysis were: retinal detachment, additional treatment, myopia (spherical equivalent) and general complication rate. Retinal fold, cataract, (description of) endophthalmitis were extracted from the individual studies. Risk of bias assessment was performed. Publication bias was investigated by a funnel plot which showed no publication bias. Authors of the review reported no conflicts of interest. There was no funding source for this study.

RCT

Lepore (2020) described the same RCT as Lepore (2018), which is included in Popovic (2021), but reported different outcome measures. The efficacy of intravitreal injections compared to photocoagulation laser treatment in patients with retinopathy of prematurity was investigated. One eye was randomized to receive an intravitreal injection of 0.5 mg bevacizumab; the fellow eye underwent conventional laser photoablation. Eighteen patients of the initial 21 patients were evaluated at 4-year follow-up. Relevant outcome measures were visual acuity and myopia. The study did not report on masking of outcome assessors. Conflicts of interests were reported for the author.

Marlow (2021) presents the 2-year follow-up results of the RAINBOW study (Stahl, 2019). See for details Stahl (2019). Of the initial randomized participants 66, 71, 64 in the ranizumab 0.2mg, ranizumab 0.1 mg or laser treatment, respectively, 15%, 25% and 31% declined or did not finish the 2 year follow up due to different reasons (see evidence table). A limitation to the study is that the funding source had full access to and were involved in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and was involved in the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit. Refraction outcomes (proportion of >-5 diopters) and visual acuity for a subgroup were relevant outcome measures.

Observational studies

Barry (2019) was a retrospective study in which the effect of intravitreal bevacizumab injections compared to panretinal photocoagulation laser treatment on retinal detachment was evaluated in children with retinopathy of prematurity. Patients that underwent treatment between September 2010 and September 2018 were included. Data of children with type I retinopathy of prematurity with a postmenstrual age of <36 weeks and ≥36 weeks were presented separately. For our analysis, only data of postmenstrual age of <36 weeks were included as laser treatment was the main treatment in children with a postmenstrual age ≥36 weeks. Thirty-four eyes received an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab and 56 eyes received laser treatment. The dose of bevacizumab varied from 0.375 to 0.625 mg per eye. The relevant outcome for this analysis was retinal detachment after 8 weeks follow-up.

Murakami (2021) was a retrospective study in which intravitreal bevacizumab injections were compared to panretinal photocoagulation laser treatment in children with retinopathy of prematurity type I. Patients that underwent treatment between October 2007 and October 2014 were included. Parents of patients were offered the choice of laser or IVB after the pros and cons of each treatment had been fully explained. Twenty-four eyes received an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab and 28 eyes received laser treatment. The dose of bevacizumab was 0.625 mg per eye. The relevant outcome for this analysis was retinal detachment after 5 years follow-up.

Ling (2020) was a retrospective study in which intravitreal bevacizumab injections were compared to panretinal photocoagulation laser treatment in children with retinopathy of prematurity type I. Patients that underwent treatment between March 2010 and February 2017 were included. Of the 340 eyes included, 61 eyes received laser treatment, 231 eyes received intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (0.625 mg), and 48 eyes received intravitreal injection of ranibizumab (0.25 mg). The relevant outcome for this analysis was retinal detachment after 75 weeks postmenstrual age.

Results

Regression rate

The critical outcome measure regression rate was reported in five RCTs (Karkhaneh, 2016; Mintz-Hittner, 2011 (BEAT-ROP study); Roohipor, 2019; Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) and Zhang, 2017). Results were reported at 1 month (Mintz-Hittner, 2011), 24 weeks (Stahl, 2019), 6 months (Zhang, 2017), and 90 weeks (Karkhaneh, 2016 and Roohipoor, 2019) follow-up.

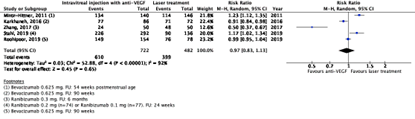

In the anti-VEGF group, 610/722 (84.5%) had regression compared to 399/482 (82.7%) in the laser treatment group. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 0.97 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.83 to 1.13), favouring anti-VEGF injections (Figure 1), which is not clinically relevant.

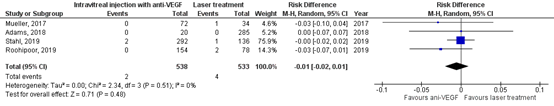

Figure 1. Results from RCTs on the outcome regression rate

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Retinal detachment

The critical outcome measure retinal detachment was reported in three RCTs and nine observational studies (Barry, 2019; Harder, 2013; Hwang, 2015; Kabatas, 2017; Lepore, 2018; Ling, 2020; Lolas, 2017; Mintz-Hittner, 2011; Mueller, 2017; Murakami, 2021; Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) and Gunay, 2017). The study of Barry (2019) was not taken into account in these analyses, because of (inexplicable) outlying results.

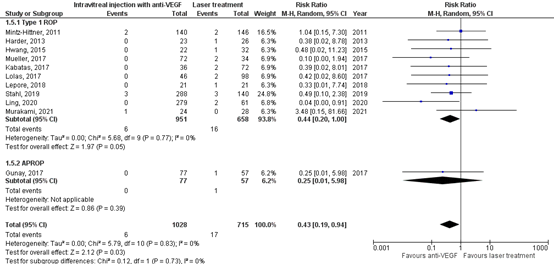

In the anti-VEGF group 6/1028 (0.6%) patients had retinal detachment, and in the control group 17/715 (2.4%) patients had retinal detachment. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.19 to 0.94), favouring anti-VEGF injections (Figure 2), which is clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Results from RCTs and observational studies on the outcome retinal detachment

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect; APROP: aggressive posterior retinopathy of prematurity.

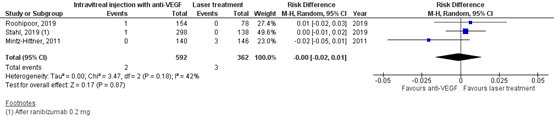

Additional treatment

The critical outcome additional treatment was reported in six RCTs (Karkhaneh, 2016; Moran, 2014; Mintz-Hittner, 2011; Roohipor, 2019; Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study) and Zhang, 2017).

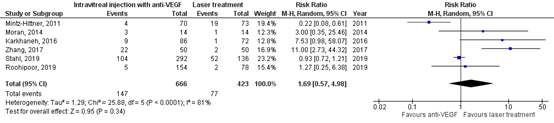

In the anti-VEGF group 143/666 (22%) patients had additional treatment, and in the laser treatment group 77/423 (18%) had additional treatment. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 1.69 (95% CI: 0.57 to 4.98), favouring laser treatment (Figure 3a), which is clinically relevant.

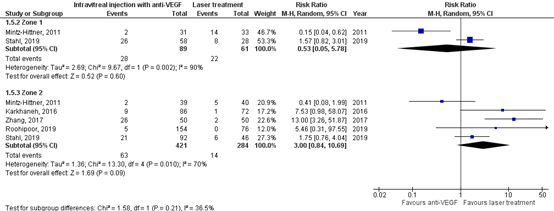

For the subgroup with patients with zone I, 28/89 (31%) had additional treatment in the anti-VEGF group, and 22/61 (36%) had additional treatment in the laser group. The pooled RR was 0.53 (95% CI: 0.05 to 5.78), favouring anti-VEGF, which is clinically relevant.

For the subgroup with patients with zone II, 63/421 (15%) had additional treatment in the anti-VEGF group, and 14/284 (5%) had additional treatment in the laser group (Figure 3b). The pooled RR waws 3.00 (95% CI: 0.84 to 10.69), favouring laser treatment, which is clinically relevant.

Figure 3a. Results from RCTs on the outcome additional treatment, total group

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Figure 3b. Results from RCTs on the outcome additional treatment, with subgroups of patients with zone I and II

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Retinal fold / retinal dragging

The important outcome measure retinal fold/retinal dragging was reported in two RCTs and two observational studies (Adams, 2019; Mueller, 2017; Roohipoor, 2019 and Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study)).

In the anti-VEGF group 2/538 (0.4%) had retinal fold/retinal dragging, and in the laser treatment group 4/533 (0.8%) had retinal fold/retinal dragging.

The pooled risk difference was -0.01 (95% CI: -0.02 to 0.01), favouring anti-VEGF injection (Figure 4), which is not clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Results from RCTs and observational studies on the outcome retinal fold/retinal dragging

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Cataract

The important outcome measure cataract was reported in three RCTs (Mintz-Hittner, 2011 (BEAT-ROP study); Roohipor, 2019 and Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study)).

In the anti-VEGF group 2/592 (0.3%) patients had cataract, and in the laser treatment group 3/362 (0.8%) patients had cataract. The pooled risk difference (RD) was 0.00 (95%CI: -0.02 to 0.01), favouring neither anti-VEGF nor laser treatment (Figure 5), which is not clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Results from RCTs on the outcome cataract

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Endophthalmitis

The important outcome measure endophthalmitis was reported in one RCT (Stahl, 2019 (RAINBOW study)).

In the anti-VEGF group 1/298 (0.3%) patients had endophthalmitis, and in the laser treatment group 0/138 (0%) patients had endophthalmitis. The risk difference was 0.00 (95% CI: -0.01 to 0.02, favouring neither anti-VEGF nor laser treatment, which is not clinically relevant.

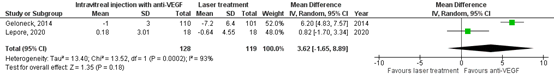

Myopia

The important outcome measure myopia (spherical equivalent) was reported in three RCTs (Geloneck, 2014; Marlow, 2021 (RAINBOW study); Lepore, 2020). Geloneck (2014) evaluated myopia at 2.5 years follow-up and Lepore (2020) at 4 years follow-up. The pooled mean difference in spherical equivalent between anti-VEGF injections and laser treatment was -3.62 diopters (95% CI: -1.65 to 8.99), favouring anti-VEGF injections, which is

a clinically relevant difference (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Results from RCTs on the outcome myopia (spherical equivalent)

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect.

Marlow (2021) reported the 2-year follow-up results of the RAINBOW study (Stahl, 2019). The spherical equivalent was not reported. High myopia (-5 diopters or worse) was present in 5/110 eyes (5%), 8/98 eyes (8%), 16/82 (20%), in the ranibizumab 0.2 mg, ranibizumab 0.1 mg and laser treatment group, respectively. After correcting for within individual correlation the prevalence of high myopia was lower in the 0.2 mg ranibizumab than in the laser therapy group (OR: 0.19, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.69, p=0.012) but did not differ between 0.1 mg ranibizumab and laser treatment (OR: 0.44, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.32, p=0.14).

Visual acuity

The important outcome measure uncorrected visual acuity was reported in one RCT (Lepore, 2020). The mean uncorrected visual acuity at 4-year follow-up after anti-VEGF injections was 0.61 (sd 0.36) and 0.71 (sd 0.43) after laser treatment. The mean difference was -0.10 (95% CI: -0.36 to 0.16), favouring laser treatment, which is a not clinically relevant. Marlow (2021) described the 2-year follow-up results of the RAINBOW study (Stahl, 2019). Formal visual acuity was reported for 67 children, without differences between the three groups.

Level of evidence of the literature

Regression (critical)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘regression’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias). The level of evidence was therefore graded as moderate.

Retinal detachment (critical)

The certainty of the evidence started low, as evidence originated from RCTs and observational studies. The level of evidence for the outcome ‘retinal detachment’ was not downgraded. The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Additional treatment (critical)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘additional treatment’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias). The level of evidence was therefore graded as moderate.

Retinal dragging/retinal fold (important)

The certainty of the evidence started low, as evidence originated from RCTs and observational studies. The level of evidence for the outcome ‘retinal dragging/retinal fold’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias), one level because of the small number of cases and the 95% confidence interval crossed the limits of decision making (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Cataract (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence for the outcome ‘cataract’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias), and by one level because of the small number of cases (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Endophthalmitis (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence for the outcome ‘endophthalmitis’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias), and two level because of the small number of cases and events and the 95% confidence interval crossed the limits of decision making (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Myopia (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence for the outcome ‘myopia’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias), and by one level because of the 95% confidence interval crossed the limits of clinically relevance (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore graded as low.

Visual acuity (important)

The certainty of the evidence started high, as evidence originated from RCTs. The level of evidence for the outcome ‘visual acuity’ was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias), and by two levels because of the small number of cases and the 95% confidence interval crossed the limits of clinically relevance (imprecision). The level of evidence was therefore graded as very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

|

P (patients) |

Patients with Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP) |

|

I (intervention) |

Intravitreal injection with anti-VEGF: bevacizumab (Avastin), ranibizumab (Lucentis) or aflibercept (Eylea) |

|

C (control) |

Laser treatment |

|

O (outcome) |

Regression, retinal detachment, additional treatment, retinal fold/retinal dragging, cataract, endophthalmitis, myopia and visual acuity |

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered regression, retinal detachment and additional treatment as critical outcome measures for decision making; and retinal fold/retinal dragging, cataract, endophthalmitis, myopia and visual acuity as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in most studies.

The guideline development group used the GRADE standard limits of 25% for dichotomous outcome measures as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference. Risk ratios were described where possible. If case studies reported no events in one of the groups, risk differences were used. A risk difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant.

The following limits were used for minimal clinically (patient) important differences per outcome:

- Regression, retinal detachment, additional treatment, retinal fold retinal dragging: GRADE standard limits of 25% for dichotomous outcome measures (RR <0.80 or RR >1.25)

- Cataract and endophthalmitis: risk difference of 10%

- Visual acuity: 1 line

- Spherical equivalent: 1 diopter

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until April 29th, 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 408 hits for systematic reviews and RCTs. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials and/or observational studies or randomized controlled trials in patients with retinopathy of prematurity, comparing anti-VEGF with laser treatment, in which reported at least one outcome of interest. Eighteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. An additional search was performed for observational studies from 2019 until April 29th, 2021. The additional systematic literature search resulted in 201 hits for observational studies. Observational studies published before 2019 were selected from the included systematic reviews (Popovic, 2021 and Wang, 2020). After reading the full text, 25 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), one study was added through snowballing and 6 studies were included.

Results

Two systematic reviews and two RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Three observational studies were additionally included for the outcome measures with low case numbers per study: retinal detachment, and retinal fold/retinal dragging. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Barry GP, Tauber KA, Fisher M, Greenberg S, Zobal-Ratner J, Binenbaum G. Short-term retinal detachment risk after treatment of type 1 retinopathy of prematurity with laser photocoagulation versus intravitreal bevacizumab. J AAPOS. 2019 Oct;23(5):260.e1-260.e4.

- Benner, J. D. (1992, January). Photocoagulation with the laser indirect ophthalmoscope for retinopathy of prematurity. In Seminars in ophthalmology (Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 177-181). Taylor & Francis.

- Chow, S. C., Lam, P. Y., Lam, W. C., & Fung, N. S. K. (2022). The role of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor in treatment of retinopathy of prematuritya current review. Eye, 1-14.

- Dikci, S., Demirel, S., F?rat, P. G., Y?lmaz, T., Ceylan, O. M., & Ba?, H. G. G. (2020). Comparison of Nd: YAG laser (532 nm green) vs diode laser (810 nm) photocoagulation in the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: an evaluation in terms of complications. Lasers in medical science, 35(6), 1323-1328.

- Furuncuoglu U, Vural A, Kural A, Onur IU, Yigit FU. Serum vascular endothelial growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1 and aflibercept levels in retinopathy of prematurity. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2022 Mar;66(2):151-158. doi: 10.1007/s10384-021-00895-9. Epub 2022 Jan 29. PMID: 35091863.

- Geloneck MM, Chuang AZ, Clark WL, Hunt MG, Norman AA, Packwood EA, Tawansy KA, Mintz-Hittner HA; BEAT-ROP Cooperative Group. Refractive outcomes following bevacizumab monotherapy compared with conventional laser treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014 Nov;132(11):1327-33.

- Huang CY, Lien R, Wang NK, Chao AN, Chen KJ, Chen TL, Hwang YS, Lai CC, Wu WC. Changes in systemic vascular endothelial growth factor levels after intravitreal injection of aflibercept in infants with retinopathy of prematurity. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018 Mar;256(3):479-487. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3878-4. Epub 2017 Dec 30. PMID: 29290015.

- Karkhaneh R, Khodabande A, Riazi-Eafahani M, Roohipoor R, Ghassemi F, Imani M, Dastjani Farahani A, Ebrahimi Adib N, Torabi H. Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab for zone-II retinopathy of prematurity. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016 Sep;94(6):e417-20.

- Lepore D, Quinn GE, Molle F, Orazi L, Baldascino A, Ji MH, Sammartino M, Sbaraglia F, Ricci D, Mercuri E. Follow-up to Age 4 Years of Treatment of Type 1 Retinopathy of Prematurity Intravitreal Bevacizumab Injection versus Laser: Fluorescein Angiographic Findings. Ophthalmology. 2018 Feb;125(2):218-226.

- Lepore D, Ji MH, Quinn GE, Amorelli GM, Orazi L, Ricci D, Mercuri E. Functional and Morphologic Findings at Four Years After Intravitreal Bevacizumab or Laser for Type 1 ROP. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2020 Mar 1;51(3):180-186.

- Ling, K. P., Liao, P. J., Wang, N. K., Chao, A. N., Chen, K. J., Chen, T. L., ... & Wu, W. C. (2020). Rates and risk factors for recurrence of retinopathy of prematurity after laser or intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor monotherapy. Retina, 40(9), 1793-1803.

- Marlow N, Stahl A, Lepore D, Fielder A, Reynolds JD, Zhu Q, Weisberger A, Stiehl DP, Fleck B; RAINBOW investigators group. 2-year outcomes of ranibizumab versus laser therapy for the treatment of very low birthweight infants with retinopathy of prematurity (RAINBOW extension study): prospective follow-up of an open label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021 Oct;5(10):698-707.

- Moran S, O'Keefe M, Hartnett C, Lanigan B, Murphy J, Donoghue V. Bevacizumab versus diode laser in stage 3 posterior retinopathy of prematurity. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014 Sep;92(6):e496-7.

- Mintz-Hittner, H. A., Kennedy, K. A., & Chuang, A. Z. (2011). Efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab for stage 3+ retinopathy of prematurity. New England Journal of Medicine, 364(7), 603-615.

- Murakami T, Sugiura Y, Okamoto F, Okamoto Y, Kato A, Hoshi S, Nagafuji M, Miyazono Y, Oshika T. Comparison of 5-year safety and efficacy of laser photocoagulation and intravitreal bevacizumab injection in retinopathy of prematurity. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021 Sep;259(9):2849-2855.

- Popovic MM, Nichani P, Muni RH, Mireskandari K, Tehrani NN, Kertes PJ. Intravitreal antivascular endothelial growth factor injection versus laser photocoagulation for retinopathy of prematurity: A meta-analysis of 3,701 eyes. Surv Ophthalmol. 2021 Jul-Aug;66(4):572-584.

- Roohipoor R, Torabi H, Karkhaneh R, Riazi-Eafahani M. Comparison of intravitreal bevacizumab injection and laser photocoagulation for type 1 zone II retinopathy of prematurity. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2018 Nov 9;31(1):61-65.

- Stahl A, Lepore D, Fielder A, Fleck B, Reynolds JD, Chiang MF, Li J, Liew M, Maier R, Zhu Q, Marlow N. Ranibizumab versus laser therapy for the treatment of very low birthweight infants with retinopathy of prematurity (RAINBOW): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 Oct 26;394(10208):1551-1559.

- Stahl A, Sukgen EA, Wu WC, Lepore D, Nakanishi H, Mazela J, Moshfeghi DM, Vitti R, Athanikar A, Chu K, Iveli P, Zhao F, Schmelter T, Leal S, Köfüncü E, Azuma N; FIREFLEYE Study Group. Effect of Intravitreal Aflibercept vs Laser Photocoagulation on Treatment Success of Retinopathy of Prematurity: The FIREFLEYE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2022 Jul 26;328(4):348-359. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.10564. PMID: 35881122; PMCID: PMC9327573.

- Spandau, U., Larsson, E., & Holmström, G. (2020). Inadequate laser coagulation is an important cause of treatment failure in type 1 retinopathy of prematurity. Acta Ophthalmologica, 98(8), 795-799.

- Trzcionkowska, K., Vehmeijer, W. B., Kerkhoff, F. T., Bauer, N. J., Bennebroek, C. A., Dijk, P. H., ... & Schalij?Delfos, N. E. (2021). Increase in treatment of retinopathy of prematurity in the Netherlands from 2010 to 2017. Acta ophthalmologica, 99(1), 97-103.

- Trzcionkowska, K., Schalij?Delfos, N. E., & van den Akker?van Marle, E. M. (2022). Cost reduction in screening for retinopathy of prematurity in the Netherlands by comparing different screening strategies. Acta Ophthalmologica.

- Yonekawa, Y., Wu, W. C., Nitulescu, C. E., Chan, R. P., Thanos, A., Thomas, B. J., ... & Capone Jr, A. (2018). Progressive retinal detachment in infants with retinopathy of prematurity treated with intravitreal bevacizumab or ranibizumab. Retina, 38(6), 1079-1083.

- Zhang, G., Yang, M., Zeng, J., Vakros, G., Su, K., Chen, M., ... & Zhuang, R. (2017). Comparison of intravitreal injection of ranibizumab versus laser therapy for zone II treatment-requiring retinopathy of prematurity. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.), 37(4), 710.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

Risk of bias tables

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1 |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2 |

Description of included and excluded studies?3 |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4 |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5 |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6 |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7 |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8 |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9 |

|

First author, year |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear |

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Popovic, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, for the inclusion, no exclusion table |

Yes (only no follow-up per study reported) |

Unclear

It was described in methods section but no information in results |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Wang, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, for the inclusion, no exclusion table. |

No, relevant information is missing |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?b |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measureg |

|

|

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Definitely yes Probably no Probably no Definitely no |

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Lepore, 2020 |

Probably yes

Reason: Eyes were randomized, minimizing patient differences, however anti-VEGF may leak into the system |

Probably yes

|

Definitely no

Reason: No masking of collectors. Patients (baby’s) were ‘masked’. |

Probably no

Reason: small loss to FU and comparable in both groups. Data were not imputed (probably best method for small sample size) |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes

Reason: Potential conflict of interest |

Some concerns |

|

Marlow, 2021 |

Probably yes |

Probably yes

|

Definitely no

Reason: No masking of collectors. Patients (baby’s) were ‘masked’. |

Definitely yes

High loss to follow up and > in laser group. |

Probably no

VA was reported for a subgroup |

Probably no

Reason: Potential conflict of interest

|

HIGH |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (observational: non-randomized clinical trials, cohort and case-control studies)

|

Study reference |

Bias due to a non-representative or ill-defined sample of patients?1 |

Bias due to insufficiently long, or incomplete follow-up, or differences in follow-up between treatment groups?2 |

Bias due to ill-defined or inadequately measured outcome ?3 |

Bias due to inadequate adjustment for all important prognostic factors?4 |

|

(first author, year of publication) |

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Barry, 2019 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

|

Ling, 2020 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

|

Murakami, 2021 |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

- Failure to develop and apply appropriate eligibility criteria: a) case-control study: under- or over-matching in case-control studies; b) cohort study: selection of exposed and unexposed from different populations.

- 2 Bias is likely if: the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large; or differs between treatment groups; or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups; or length of follow-up differs between treatment groups or is too short. The risk of bias is unclear if: the number of patients lost to follow-up; or the reasons why, are not reported.

- Flawed measurement, or differences in measurement of outcome in treatment and control group; bias may also result from a lack of blinding of those assessing outcomes (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Failure to adequately measure all known prognostic factors and/or failure to adequately adjust for these factors in multivariate statistical analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Anand, 2019 |

Different comparison |

|

Barry, 2020 |

Different research aim, different outcomes |

|

Chmielarz-Czarnocińska, 2021 |

Different comparison |

|

Chen, 2020 |

Different research aim, different outcomes |

|

Demir, 2019 |

Patients received multiple treatments and small cohort |

|

Ekinci, 2020 |

Patients received multiple treatments and different outcomes |

|

Geloneck, 2014 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2021 |

|

Kang, 2019 |

Different research aim, different outcomes |

|

Karkhaneh, 2016 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2021 |

|

Kennedy, 2018 |

Only non-ophthalmological outcome measures reported (secondary analysis op BEAT-ROP) study |

|

Lepore, 2014 |

Same population as Lepore, 2018 and no additional outcomes |

|

Lepore, 2018 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2021 |

|

Li, 2018 |

Same studies as Popovic, 2021 or Wang, 2020 or not matching to PICO |

|

Martínez-Castellanos, 2020 |

No comparison |

|

Mintz-Hittner, 2011 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2020 |

|

Moran, 2014 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2020 |

|

O’Keeffe, 2016 |

Small RCT, patients were randomized but received multiple treatments, data selectively reported. |

|

Pertl, 2015 |

Same studies as Popovic, 2021 or Wang, 2020 or not matching to PICO |

|

Rohipoor, 2019 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2020 |

|

Stahl, 2019 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2020 |

|

VanderVeen, 2017 |

All studies that match the PICO are also included in Popovic, 2021 or Wang, 2020. Other studies (Anti-VEGF + laser or subgroup (patients <1500g). |

|

Xiong, 2021 |

Fulltext not available |

|

Zayek, 2020 |

Different comparison |

|

Zhang, 2017 |

Not included as individual study but as part of the systematic review of Popovic, 2020 |

|

Zhang, 2020 |

Different inclusion criteria |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 13-11-2023

Laatst geautoriseerd : 13-11-2023

Geplande herbeoordeling :

Algemene gegevens

De herziening van deze richtlijn werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met prematurenretinopathie (ROP).

Samenstelling van de werkgroep

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. N.E. (Nicoline) Schalij-Delfos, hoogleraar oogheelkunde, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden (NOG)

- Dr. A.J. (Arlette) van Sorge, oogarts, Koninklijke Visio, Amsterdam (NOG)

- Drs. I.L.A. (Irene) van Liempt, oogarts, Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda (NOG)

- Dr. F.T. (Frank) Kerkhoff, oogarts, Máxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven (NOG)

- Drs. S.J.R. (Stefan) de Geus, oogarts, Máxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven (NOG)

- Drs. K. (Kasia) Trzcionkowska, oogarts in opleiding, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden (NOG)

- Drs. E. (Elke) Kraal-Biezen, oogarts, Amsterdam Universitair Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam (NOG)

- Dr. J.U.M. (Jacqueline) Termote, neonatoloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht, Utrecht (NVK)

- Drs. J.L.A.M. (Jacqueline) van Hillegersberg-Schilder, kinderarts-neonatoloog, Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein (NVK)

- Dr. G.J. (Gert Jan) van Steenbrugge, patiëntvertegenwoordiger (Care4Neo)

Klankbordgroep

- Drs. I. (Irma) Endeman, neonatologie verpleegkundige, Alrijne Zorggroep, Leiden (V&VN)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. A. (Anja) van der Hout, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. B.L. (Babette) Gal-de Geest, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Schalij-Delfos |

Oogarts LUMC |

Geen |

Data Monitoring Committee Rainbouwstucie (gebruik ranibizumab bij ROP). Geen betrokkenheid bij publicaties, geen actieve deelname met patiënten aan studie. Alleen data safety monitoring. Vergoeding naar afdeling Oogheelkunde, niet naar mij persoonlijk |

Geen restricties |

|

Trzcionkowska |

AIOS Oogheelkunde/Promovenda LUMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Kraal-Biezen |

Oogarts, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Termote |

Neonatoloog, UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Sorge |

- Oogarts Koninklijke Visio (3 dagen/week) - Kinderoogarts (1 dag/week) Amsterdam UMC, locatie AMC Amsterdam |

Wetenschappelijke nul-aanstelling (onbetaald) bij het AmsterdamUMC tot 01-01-2021

Richtlijn visusstoornissen (vacatiegelden)

Stuurgroeplid cluster Oog van het NOG (vacatiegelden).

Voorzitter van de Vereniging voor Revalidatie bij Slechtziendheid (VRS) (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Hillegersberg |

Kinderarts-neonatoloog st. Antonius Ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Steenbrugge |

Ervaringsdeskundige, ouder van twee ex-couveusekinderen. Voormalig directeur bij de patiënten-ouderorganisatie, Ver. van Ouders van Couveusekinderen, thans Care4Neo. Gepensioneerd en op vrijwillige basis betrokken bij Care4Neo als belangenbehartiger onderzoek en medische issues.

|

Lid cliëntenraad Erasmus MC (vrijwillig met vacatie vergoeding) Bestuurslid Hoormij-NVVS, de organisatie voor mensen met een auditieve beperking (november 2020 aftredend). Onbetaald. Vertegenwoordiger Care4Neo in de EFCNI (European Foundation tor the Care of Newborn lnfants). Onbetaald. |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Van Liempt |

- Oogarts Amphia Ziekenhuis Breda - Oogarts (consulent) Koninklijke VISIO (1dag/3wk) |

Voorzitter beroepsbelangen commissie van wetenschappelijke vereniging NOG (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Kerkhoff |

Werkzaamheden als oogarts in MMC per 31-1-2023 gestopt, werkzaam als oogarts en medisch directeur bij FYEO en loop van het jaar voor de ROP werkzaam in UMC Radboud. |

Medisch Directeur FYEO Medical |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

De Geus |

Oogarts, Maxima Medisch Centrum (MMC) |

Geen |

PI namens MMC bij "Firefleye" onderzoek (Eylea bij ROP). Onderzoek wordt gefinancierd door Bayer (Financiële vergoeding naar MMC). |

Geen restricties, betrokkenheid bij het Firefleye onderzoek betreft slechts de inclusie van een proefpersoon. |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitnodigen van de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, de Oogvereniging, en Care4Neo voor de schriftelijke knelpuntenanalyse, een afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging in de werkgroep en klankbordgroep en een enquête uitgezet door Care4Neo. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis en de Oogvereniging en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Inclusiecriteria screening |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Screeningsschema ROP |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Logistiek rondom ROP screening |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Behandelcriteria en -opties ROP |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Invloed van zuurstof op progressie ROP |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Invloed van Hb op het beloop van ROP |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Overplaatsing en verwijzing bij ROP |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

|

Module Het informeren van ouders over ROP |

Geen financiële gevolgen |