Niet-medicamenteuze interventies

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de plaats van niet-medicamenteuze interventies bij patiënten die een chirurgische procedure ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het gebruik van niet-medicamenteuze interventies ter aanvulling op de postoperatieve pijnbehandeling, ter vermindering van angst en vergroting van comfort en de patiënttevredenheid.

Overweeg binnen de lokale instelling een aantal aanvullende, niet-invasieve technieken te faciliteren als niet-medicamenteuze opties voor de behandeling van postoperatieve pijn.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar de effectiviteit van niet-medicamenteuze interventies op postoperatieve pijn. Hierbij is gekeken naar interventies in drie categorieën, namelijk: 1) massage en relaxatie, 2) communicatie en therapeutische suggestie en 3) virtual reality.

Postoperatieve pijn was de cruciale uitkomstmaat, welke is onderzocht voor de drie categorieën. Voor de categorie ‘massage en relaxatie’ werden er drie systematische reviews, die 4, 5 en 8 studies beschreven, en 13 individuele gerandomiseerde gecontroleerde studies (RCTs) geïncludeerd. Voor de categorie ‘communicatie en therapeutische suggestie’ werden er vier individuele studies geïdentificeerd. Voor de categorie ‘virtual reality’ werden er 1 systematische review die 8 studies beschreef en 1 individuele RCT geïncludeerd.

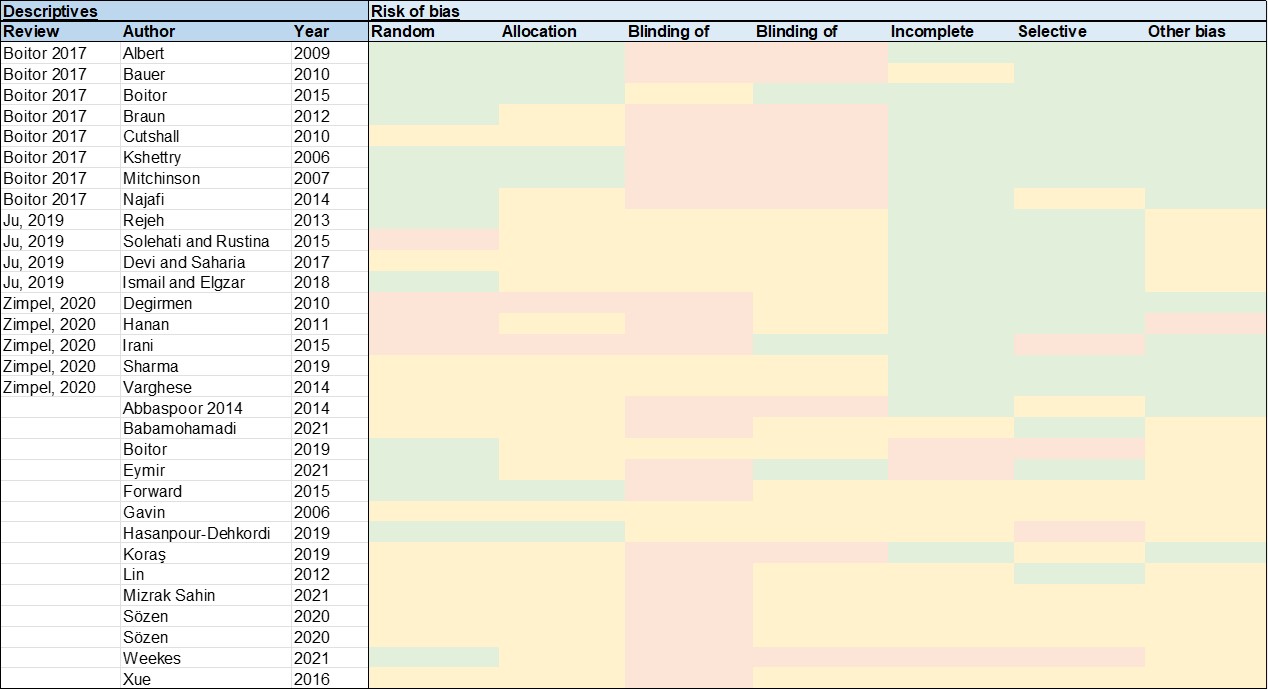

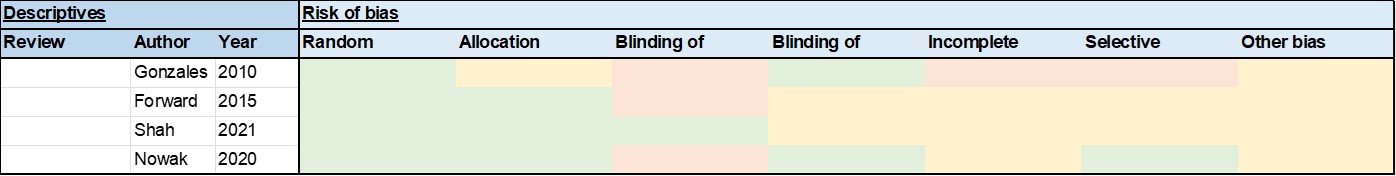

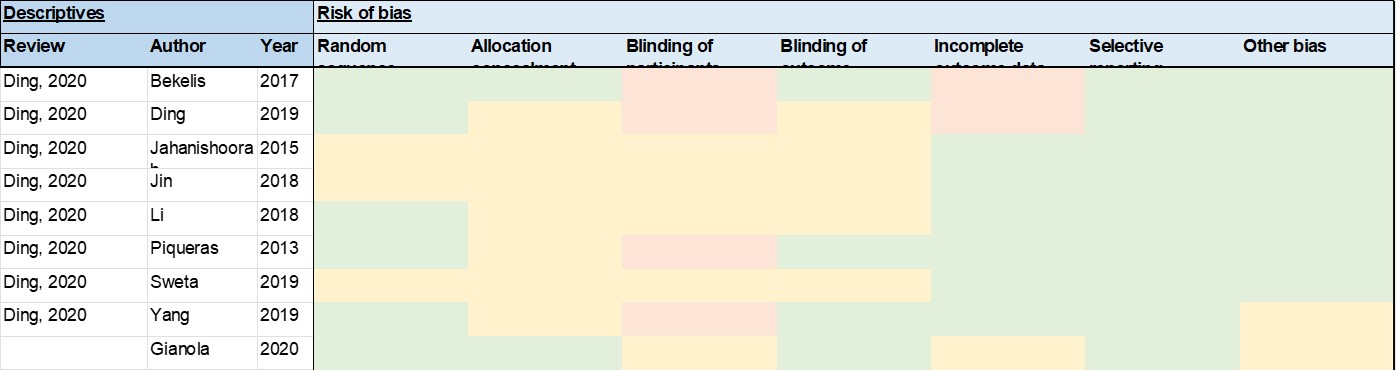

De studies waren heterogeen in studiepopulatie, type chirurgie, interventie en follow-up (zie tabel 1). De studies waren vaak niet adequaat gerandomiseerd, de maskering van randomisatie was niet adequaat of niet beschreven, de blindering was vaak beperkt, dataverwerking, de analyses en ontbrekende data waren niet goed beschreven en veel trials waren niet geregistreerd. Hierom is bij alle drie de categorieën afgewaardeerd voor methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias, -1). Aanvullend werd afgewaardeerd voor het overschrijven van de grenzen van klinische relevantie (imprecisie, -1) of inclusie van in totaal relatief weinig patiënten (imprecisie, -1). De bewijskracht van de literatuur voor alle drie de categorieën was laag (low GRADE). Hiermee is de overall bewijskracht laag.

De resultaten van de studies in alle drie de categorieën lieten kleine positieve effecten zien. Voor de categorie massage en relaxatie bereikte het verschil de grens van klinische relevantie. Hierdoor kan, met een lage bewijskracht, gezegd worden dat dit type interventie mogelijk de postoperatieve pijn vermindert.

Interventies in de categorieën communicatie en therapeutische suggestie en ook virtual reality lieten kleine positieve effecten zien, maar deze bereikten de grens van klinische relevantie (-1 punt/10 punten) niet.

Op basis van de resultaten met lage bewijskracht kan er richting gegeven worden aan de besluitvorming.

Niet-medicamenteuze interventies kunnen toegevoegd worden aan bestaande medicamenteuze interventies. De werking van niet-medicamenteuze interventies op pijn is niet altijd duidelijk. Indien interventies een positief effect hebben op bijvoorbeeld angst en spanning, zal dit ook de ervaren pijn positief beïnvloeden.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van het gebruik van niet-medicamenteuze interventies is allereerst de vermindering van postoperatieve pijn. Daarnaast kunnen deze interventies bijdragen aan de ontspanning en afleiding van de patiënt alsmede het verminderen van angst en vergroten van de patiënttevredenheid. Voor het gebruik van ontspannende massage en positief taalgebruik geldt dat er geen bijwerkingen worden ervaren. De virtual reality bril kan wel voor enige desoriëntatie of misselijkheid zorgen.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Ontspannende massages worden in sommige ziekenhuizen reeds aangeboden met behulp van vrijwilligers en brengen derhalve geen grote kosten met zich mee. Het scholen van medewerkers in positief taalgebruik vergt wel een investering, evenals de aanschaf van een virtual reality bril en software.

Er is weinig bekend over de kosteneffectiviteit van deze interventies. De interventies lijken over het algemeen eenvoudig uitvoerbaar en de kosten lijken beperkt. Daardoor zou het een relatief goedkope manier zijn om de patiëntbeleving positief te beïnvloeden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De keuze van de interventie is zeer sterk afhankelijk van de voorkeur van de patiënt. Niet iedereen staat bijvoorbeeld open voor massage of het gebruik van positieve taal. Wat voor de één ontspannend werkt, werkt bij een ander wellicht helemaal niet. Er lijkt vanuit de literatuur wel een positief effect te komen voor het gebruik van deze interventies ten aanzien van pijn en patiënttevredenheid. Derhalve is het een overweging om een scala aan niet-medicamenteuze technieken te kunnen aanbieden binnen de instelling naar de lokale voorkeuren en mogelijkheden. Een belangrijke voorwaarde voor het gebruik van de interventies is dat de zorgprofessionals op de hoogte zijn van de mogelijkheden en dat allen betrokken bij de zorg op dezelfde wijze communiceren en de positieve invloed van deze interventies uitdragen (bijv. bij positief taalgebruik, maar niet alleen hierbij).

Het op juiste wijze uitvoeren van de interventies vraagt om training, waarvan voor sommige interventies mogelijk in de praktijk te oefenen zijn. Voor andere interventies, zoals hypnose, is uitgebreide scholing nodig.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De werkgroep ziet potentiële voordelen in het gebruik van niet-medicamenteuze interventies als aanvulling op medicamenteuze therapie ten behoeve van de bestrijding van postoperatieve pijn. Er zijn echter vele niet-medicamenteuze methoden beschikbaar ter afleiding, ontspanning of pijnbestrijding, welke niet allemaal in deze richtlijn zijn onderzocht (bijv. muziek, medische hypnose). Velen van deze methoden zijn relatief makkelijk in te zetten en geven weinig tot geen bijwerkingen. Het gebruik van deze technieken hangt af van de pijndiagnostiek, voorkeur van de patiënt, de lokale beschikbaarheid van noodzakelijke materialen en eventueel (scholing van) personeel.

Het is echter belangrijk dat deze methoden gezien het beperkte effect op pijn (met lage bewijskracht) alleen als aanvullend in combinatie met medicamenteuze interventies ingezet kunnen worden.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De huidige situatie is dat er bij het behandelen van postoperatieve pijn veelal medicamenteuze interventies worden toegepast, die systemische bijwerkingen kunnen hebben. Niet-medicamenteuze interventies kunnen de nociceptieve processen in het perifere en centrale zenuwstelsel op verschillende manieren beïnvloeden. Zij dienen ingezet te worden op basis van de bevindingen bij pijndiagnostiek. Zo kan bij zwelling een lidmaat hoog worden gelegd of koude worden toegepast (‘basis’ niet-medicamenteuze interventies).

Wat vaak voorkomt, is een verhoogde arousal in het centrale zenuwstelsel door angst of negatieve verwachtingen, waardoor nociceptie versterkt wordt waargenomen en de pijnbeleving negatief beïnvloed. Het hebben van vertrouwen, comfort en positieve gedachten kan een gunstig effect hebben. Niet-medicamenteuze technieken, gebaseerd op ontspanning, afleiding en het toevoegen van comfort kunnen een belangrijke interventie zijn met weinig extra kosten en/of bijwerkingen.

Er zijn vele niet-medicamenteuze methoden beschikbaar ter afleiding, ontspanning en het aanbrengen van meer comfort. In het kader van deze richtlijn ligt de focus op ontspannende massage, positief taalgebruik en het gebruik van virtual reality.

Er bestaat echter ook literatuur ten aanzien van het gebruik van muziek, medische hypnose en verschillende afleidingstechnieken (welke bijvoorbeeld ook gebruikt worden door de zorgverleners binnen de kindergeneeskunde). Voor het gebruik van muziek verwijzen wij naar de modules ‘muziek in de operatiekamer’. Muziek kan worden ingezet om pijn en angst bij de patiënt te verminderen. Muziek kan in overleg met de patiënt worden aangeboden tijdens de operatie, op de verkoeverkamer en tijdens het postoperatieve verblijft. Hierbij worden de kenmerken van de muziek (frequentie, duur, genre en volume) afgestemd op de voorkeuren van de patiënt. (Muziek rondom de operatie - Richtlijn - Richtlijnendatabase)

Er is ook toenemend bewijs voor het positieve effect van hypnose op postoperatieve pijn (Kekecs, 2014). Daarbij moet nadrukkelijk vermeld worden dat niet iedereen hypnose kan uitvoeren en dat er scholing nodig is voor adequate behandeling van patiënten met hypnose.

Conclusies

|

Low GRADE |

Massage and relaxation interventions may result in less postoperative pain when compared to standard of care or sham procedure in adult surgical patients.

Source: Boitor, 2017, Ju, 2019; Abbaspoor, 2014; Babamohamadi, 2021; Boitor, 2019; Eymir, 2021; Forward, 2015; Gavin, 2006; Hasanpour-Dehkordi, 2019; Koraş, 2019; Lin, 2012; Mizrak Sahin, 2021; Sözen, 2020; Weekes, 2021; Xue, 2016. |

|

Low GRADE |

Communication and therapeutic suggestion interventions may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain when compared to standard of care or sham procedure in adult surgical patients.

Source: Gonzales, 2010; Forward, 2015; Shah, 2021; Nowak, 2020. |

|

Low GRADE |

Virtual reality interventions may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain when compared to standard of care or sham procedure in adult surgical patients.

Source: Ding, 2020; Gianola, 2020. |

Samenvatting literatuur

A total of 43 studies (25 from systematic review and 18 single RCTs) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Description of studies

The main characteristics of the studies are provided in Table 1. Different controls were used and studies were conducted in different type of surgery settings. Additional information can be found in the ‘evidence tables’.

Three systematic reviews were included, describing 8, 4 and 5 studies that met the PICO respectively. In addition, 13 individual RCTs were included. The number of patients per arm varied from 15 to 202. In total, 1655 patients were included in the intervention group and 1541 patients in the control group.

Table 1. Study descriptions.

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

N intervention group |

N control group |

Surgery type |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Albert |

2009 |

126 |

126 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

Standard of care |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Bauer |

2010 |

62 |

51 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

standard care with quiet relaxation |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Boitor |

2015 |

21 |

19 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - hand |

sham massage |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Braun |

2012 |

75 |

71 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

standard care |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Cutshall |

2010 |

30 |

28 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

standard care with quiet time |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Kshettry |

2006 |

49 |

50 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - NS |

standard care with rest period |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Mitchinson |

2007 |

200 |

202 |

64% cardiac surgery requiring sternal incision & 36% abdominal surgery |

Massage - back |

attention control; Comparator 2: |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Najafi |

2014 |

35 |

35 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft |

Massage - body |

attention control |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Rejeh |

2013 |

62 |

62 |

NS |

Systematic relaxation |

NS |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Solehati and Rustina |

2015 |

30 |

30 |

Caesarean |

Benson's relaxation |

NS |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Devi and Saharia |

2017 |

20 |

20 |

Appendicectomy, cholecystectomy, hernioplasty, gastrectomy, gastro-jejunostomy |

Progressive muscle relaxation |

NS |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Ismail and Elgzar |

2018 |

40 |

40 |

Caesarean |

Progressive muscle relaxation |

NS |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Degirmen |

2010 |

50 |

25 |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand and or foot |

standard of care |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Hanan |

2011 |

75 |

75 |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

standard of care |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Irani |

2015 |

40 |

40 |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

standard of care |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Sharma |

2019 |

30 |

30 |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

standard of care |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Varghese |

2014 |

30 |

30 |

Caesarean |

Foot reflexology |

standard of care |

|

|

Abbaspoor |

2014 |

40 |

40 |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

attention |

|

|

Babamohamadi |

2021 |

30 |

30 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery |

rhythmic breathing |

Standard of care |

|

|

Boitor |

2019 |

20 |

20 |

Cardiac surgery patients |

Massage - hand |

Standard of care |

|

|

Eymir |

2021 |

55 |

51 |

total knee arthroplasty |

progressive muscle relaxation |

standard physiotherapy alone |

|

|

Forward |

2015 |

75 |

74 |

hip replacement or knee replacement |

M-technique (registered method of structured touch) |

Standard of care |

|

|

Gavin |

2006 |

31 |

27 |

lumbar and spinal surgery |

preoperative relaxation training |

standard preparation alone |

|

|

Hasanpour-Dehkordi |

2019 |

35 |

35 |

gastrointestinal tract surgery |

Progressive muscle relaxation |

standard preparation alone |

|

|

Koraş |

2019 |

85 |

82 |

laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery |

Massage - foot |

Standard of care |

|

|

Lin |

2012 |

45 |

48 |

joint replacement surgery |

breath relaxation and guided imagery tape |

Standard of care |

|

|

Mizrak Sahin |

2021 |

15 |

15 |

Gynecologic Surgery |

Massage - NS |

Standard of care |

|

|

Sözen |

2020 |

65 |

34 |

laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Massage - hand |

Standard of care |

|

|

Sözen |

2020 |

63 |

34 |

laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Massage - foot |

Standard of care |

|

|

Weekes |

2021 |

74 |

72 |

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair |

relaxation, breathing exercises |

Standard of care |

|

|

Xue |

2016 |

47 |

45 |

Caesarean delivery |

Massage - foot |

Standard of care |

This table presents the author and year, type of surgery, intervention and control regime and number of patients that were included in the study. NS: not specified;

Results

1. Postoperative pain

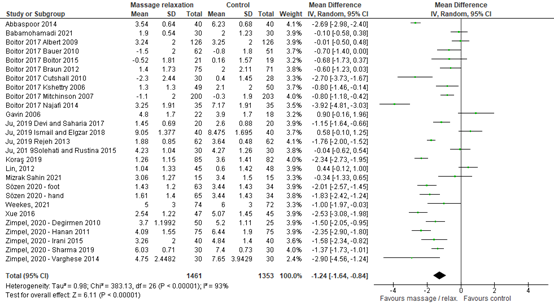

All of the 26 studies reported postoperative pain. As 24 studies reported the mean (SD) pain score, these studies were pooled in a meta-analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1: Pain scores ‘massage and relaxation’ studies.

This figure shows the individual study results of studies on the effect of massage and relaxation on postoperative pain. Study details can be found in Table 1 and in the evidence table.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

The pooled analysis shows a standardized mean difference of -1.24 (95% CI -1.64 to -0.84), in favour of the intervention group. This difference does reach the threshold for clinically relevant (-1 point).

Four studies did not report the mean (SD) result and are therefore reported separately.

- Boitor (2019) reported that the median (IQR) pain score was 0 (0 - 7) in the intervention group and 2 (0 - 4.5) in the control group. The median difference was 2, which is a clinically relevant difference in favour of the intervention group.

- Eymir (2021) reported that the median (IQR) pain score was 3.0 (IQR 2.0 - 4.0) in the intervention group and 3.0 (2.0 - 5.0) in the control group. This indicates no difference between groups.

- Forward (2015) reported a mean pain score of 2.6 for the intervention group and 3.6 for the control group. SDs were not provided. The mean difference of 1.0 could be interpreted as a clinically relevant difference, in favour of the intervention group. As the SD is missing, the imprecision of these results cannot be evaluated.

- Hasanpour-Dehkordi (2019) used a continuous scale to assess pain and reported pain severity in 4 categories. It is unclear which scores are included in which categories. In the intervention group, 77% of the patients reported a very low pain level and 23% a low pain level. In the control group, 65% of the patients reported a very low pain level and 35% reported a low pain level. None of the patients reported intermediate or severe pain. It cannot be assessed whether this difference between groups is clinically relevant as the definition of the categories is lacking.

Taken together, the results in this category vary from ‘no difference between groups’ to ‘a clinically relevant difference in favour of the intervention group’.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias -1) and crossing the threshold of clinical relevance (imprecision -1). The level of evidence is low (GRADE).

PICO 2: Communication and therapeutic suggestion

Summary of literature

Description of studies

Four individual RCTs were included. The number of patients per arm varied from 16 to 194. In total, 304 patients were included in the intervention group and 306 patients in the control group.

Table 2. Study descriptions.

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

N intervention group |

N control group |

Surgery type |

Intervention |

Control |

|

|

Gonzales |

2010 |

22 |

22 |

same-day surgical procedures |

Guided imagery |

no intervention |

|

|

Forward |

2015 |

75 |

74 |

hip replacement or knee replacement |

Guided imagery |

Standard of care |

|

|

Shah |

2021 |

16 |

16 |

vaginal hysterectomy with minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy |

therapeutic suggestion |

Standard of care |

|

|

Nowak |

2020 |

191 |

194 |

surgery for 1-3 hours under general anaesthesia |

audiotape of background music and positive suggestions |

blank tape |

This table presents the author and year, type of surgery, intervention and control regime and number of patients that were included in the study. NS: not specified;

Results

1. Postoperative pain

Four studies reported postoperative pain scores after a ‘communication and therapeutic suggestion’ intervention. The studies reported the mean (SD), mean without SD or median (IQR scores). Therefore, results were not pooled.

Gonzales (2010) reported that the mean (SD) score was 20.00 (28.92) in the intervention group and 34.72 (27.54) in the control group (scale 0-100). The MD was -14.72 (95% CI -31.41 to 1.97), in favour of the intervention group. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Forward (2015) reported that the mean pain score was 2.9 in the intervention group and 3.5 in the control group. No SDs were available. The MD was -0.6, which was not considered clinically relevant.

Shah (2021) reported that the median (IQR) pain score was 4 (3 – 5) in the intervention group and 4 (3 – 5) in the control group, indicating no difference between groups.

Nowask (2020) reported that the median (IQR) score was 4 (3 – 6) in the intervention group and 5 (4 – 7) in the control group. The median difference was -1, in favour of the intervention group. This indicates a clinically relevant difference between groups.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias -1) and number of included patients (imprecision -1). The level of evidence is low (GRADE).

PICO 3: Virtual reality

Summary of literature

Description of studies

One systematic review describing 8 studies that met the PICO was identified. In addition, one individual RCT was included. The number of patients per arm varied from 15 to 91. In total, 407 patients were included in the intervention group and 401 patients in the control group.

Table 3. Study descriptions.

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

N intervention group |

N control group |

Surgery type |

Intervention |

Control |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Bekelis |

2017 |

64 |

63 |

Craniotomy/spine surgery |

Virtual reality |

routine audiovisual descriptions of the operative experience |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Ding |

2019 |

91 |

91 |

Hemorrhoidectomy |

Virtual reality |

Standard pharmacological analgesic intervention |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Jahanishoorab |

2015 |

15 |

15 |

Episiotomy repair |

Virtual reality |

Pharmacological anesthesia |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Jin |

2018 |

33 |

33 |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Conventional rehabilitation protocol |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Li |

2018 |

39 |

39 |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Conventional rehabilitation protocol |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Piqueras |

2013 |

72 |

70 |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Standard clinical protocol of rehabilitation |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Sweta |

2019 |

25 |

25 |

Dental surgery |

Virtual reality |

Local anesthesia |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Yang |

2019 |

24 |

24 |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

standard preoperative information |

|

|

Gianola |

2020 |

44 |

41 |

total knee arthroplasty |

Virtual reality |

traditional rehabilitation |

This table presents the author and year, type of surgery, intervention and control regime and number of patients that were included in the study. NS: not specified;

Results

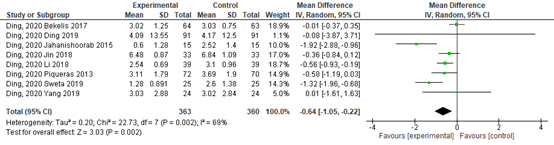

1. Postoperative pain

For eight studies, the mean (SD) pain score using a VAS scale (0 – 10 points; a higher score indicates more pain) was reported. Figure 2 shows the mean differences of the separate studies. The pooled mean difference was -0.64 (95% CI -1.05 to -0.22). This is not considered a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 2: Pain scores ‘virtual reality’ studies.

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

Gianola (2020) reported the mean VAS (0-100) difference before en after the intervention. The difference was -23.03 (95% CI -0.26 to -15.79) in the intervention group and -28.97 (95% CI -36.82 to -1.12) in the control group. The difference between these difference scores was -5.94, which is not considered clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain started as high, because the studies were RCTs. The level of evidence was downgraded by two levels because of study limitations (risk of bias -1) and number of included patients (imprecision -1). The level of evidence is low (GRADE).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of adding non-pharmacological interventions perioperatively to standard care in surgical patients on postoperative pain, adverse outcomes and rescue analgesic consumption?

Three PICOs were defined:

P patients: Surgical patients.

I intervention: non-pharmacological intervention + standard of care:

I-1: massage and relaxation

I-2: communication and therapeutic suggestion

I-3: virtual reality

C control: Standard of care (+ sham intervention).

O outcome measure: Postoperative pain.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered postoperative pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making. The working group defined the outcome measure as follows:

Validated pain scale (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) or Verbal Rating Scale (VRS)) at post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) arrival.

A priori, the working group did not define the other outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. The working group defined one point as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference on a 10-point pain score and 10 mm on a 100 mm pain scale.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 21-7-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1881 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review or randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

- Published ≥ 2000

- Patients ≥ 18 years

- Conform PICO

A total of 115 studies was initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 94 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and one study was additionally identified. Four reviews and 18 individuals RCTs were included, describing 43 studies in total.

Results will be provided separately for three categories:

PICO 1: massage and relaxation

PICO 2: communication and therapeutic suggestion

PICO 3: virtual reality

Referenties

- Abbaspoor Z, Akbari M, Najar S. Effect of foot and hand massage in post-cesarean section pain control: a randomized control trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014 Mar;15(1):132-6. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2012.07.008. Epub 2013 Jan 24. PMID: 23352729.

- Babamohamadi H, Karkeabadi M, Ebrahimian A. The Effect of Rhythmic Breathing on the Severity of Sternotomy Pain after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021 Jun 10;2021:9933876. doi: 10.1155/2021/9933876. PMID: 34221093; PMCID: PMC8213490.

- Boitor M, Martorella G, Maheu C, Laizner AM, Gélinas C. Does Hand Massage Have Sustained Effects on Pain Intensity and Pain-Related Interference in the Cardiac Surgery Critically Ill? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019 Dec;20(6):572-579. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2019.02.011. Epub 2019 May 15. PMID: 31103505.

- Boitor M, Gélinas C, Richard-Lalonde M, Thombs BD. The Effect of Massage on Acute Postoperative Pain in Critically and Acutely Ill Adults Post-thoracic Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Heart Lung. 2017 Sep-Oct;46(5):339-346. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.05.005. Epub 2017 Jun 12. PMID: 28619390.

- Ding L, Hua H, Zhu H, Zhu S, Lu J, Zhao K, Xu Q. Effects of virtual reality on relieving postoperative pain in surgical patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020 Oct;82:87-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.08.033. Epub 2020 Aug 31. PMID: 32882400.

- Eymir M, Unver B, Karatosun V. Relaxation exercise therapy improves pain, muscle strength, and kinesiophobia following total knee arthroplasty in the short term: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2022 Aug;30(8):2776-2785. doi: 10.1007/s00167-021-06657-x. Epub 2021 Jul 6. PMID: 34230983.

- Forward JB, Greuter NE, Crisall SJ, Lester HF. Effect of Structured Touch and Guided Imagery for Pain and Anxiety in Elective Joint Replacement Patients--A Randomized Controlled Trial: M-TIJRP. Perm J. 2015 Fall;19(4):18-28. doi: 10.7812/TPP/14-236. Epub 2015 Jul 24. PMID: 26222093; PMCID: PMC4625990.

- Gavin M, Litt M, Khan A, Onyiuke H, Kozol R. A prospective, randomized trial of cognitive intervention for postoperative pain. Am Surg. 2006 May;72(5):414-8. PMID: 16719196.

- Gianola S, Stucovitz E, Castellini G, Mascali M, Vanni F, Tramacere I, Banfi G, Tornese D. Effects of early virtual reality-based rehabilitation in patients with total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Feb;99(7):e19136. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019136. PMID: 32049833; PMCID: PMC7035049.

- Gonzales EA, Ledesma RJ, McAllister DJ, Perry SM, Dyer CA, Maye JP. Effects of guided imagery on postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing same-day surgical procedures: a randomized, single-blind study. AANA J. 2010 Jun;78(3):181-8. PMID: 20572403.

- Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Solati K, Tali SS, Dayani MA. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation with analgesic on anxiety status and pain in surgical patients. Br J Nurs. 2019 Feb 14;28(3):174-178. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2019.28.3.174. PMID: 30746976.

- Ju W, Ren L, Chen J, Du Y. Efficacy of relaxation therapy as an effective nursing intervention for post-operative pain relief in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2019 Oct;18(4):2909-2916. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7915. Epub 2019 Aug 19. PMID: 31555379; PMCID: PMC6755420.

- Kekecs Z, Nagy T, Varga K. The effectiveness of suggestive techniques in reducing postoperative side effects: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2014 Dec;119(6):1407-19. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000466. PMID: 25289661.

- Kora? K, Karabulut N. The Effect of Foot Massage on Postoperative Pain and Anxiety Levels in Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Experimental Study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2019 Jun;34(3):551-558. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.07.006. Epub 2018 Nov 20. PMID: 30470466.

- Lin PC. An evaluation of the effectiveness of relaxation therapy for patients receiving joint replacement surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2012 Mar;21(5-6):601-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03406.x. Epub 2011 Feb 9. PMID: 21306457.

- Mizrak Sahin B, Culha I, Gursoy E, Yalcin OT. Effect of Massage With Lavender Oil on Postoperative Pain Level of Patients Who Underwent Gynecologic Surgery: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2021 Jul-Aug 01;35(4):221-229. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000400. PMID: 32657903.

- Nowak H, Zech N, Asmussen S, Rahmel T, Tryba M, Oprea G, Grause L, Schork K, Moeller M, Loeser J, Gyarmati K, Mittler C, Saller T, Zagler A, Lutz K, Adamzik M, Hansen E. Effect of therapeutic suggestions during general anaesthesia on postoperative pain and opioid use: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2020 Dec 10;371:m4284. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4284. PMID: 33303476; PMCID: PMC7726311.

- Shah NM, Andriani LA, Mofidi JL, Ingraham CF, Tefera EA, Iglesia CB. Therapeutic Suggestion in Postoperative Pain Control: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021 Jul 1;27(7):409-414. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000906. PMID: 32541300.

- Sözen KK, Karabulut N. Efficacy of Hand and Foot Massage in Anxiety and Pain Management Following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: A Controlled Randomized Study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2020 Apr;30(2):111-116. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000738. PMID: 31855924.

- Weekes DG, Campbell RE, Wicks ED, Hadley CJ, Chaudhry ZS, Carter AH, Pepe MD, Tucker BS, Freedman KB, Tjoumakaris FP. Do Relaxation Exercises Decrease Pain After Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021 May 1;479(5):870-884. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001723. PMID: 33835103; PMCID: PMC8051979.

- Xue M, Fan L, Ge LN, Zhang Y, Ge JL, Gu J, Wang Y, Chen Y. Postoperative Foot Massage for Patients after Caesarean Delivery. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2016 Aug;220(4):173-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-104802. Epub 2016 Aug 10. PMID: 27509141.

- Zimpel SA, Torloni MR, Porfírio GJ, Flumignan RL, da Silva EM. Complementary and alternative therapies for post-caesarean pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020 Sep 1;9:CD011216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011216.pub2. PMID: 32871021.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

(per category; first study descriptives, then results)

Massage and relaxation

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

N INT |

N CNTL |

Age Sex |

Surgery |

Intervention |

Regime |

Control |

Regime |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Albert |

2009 |

126 |

126 |

65 (SD 12) Male: 73% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

Duration: 30 Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: 2 Protocol: specific (back, arms, legs) |

standard care |

Duration: - Frequency**: - Sessions: - |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Bauer |

2010 |

62 |

51 |

66 (SD 13) Male: 69% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

Duration: 20 min Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: 2 Protocol: specific (hands, feet, back, arms, legs, neck, shoulders, head, pt preference) |

standard care with quiet relaxation |

Duration: 20 min Frequency**: 1 Sessions: 2 |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Boitor |

2015 |

21 |

19 |

67 (SD 11) Male: 78% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - hand |

Duration: 15 min Frequency/day: 2e3 Sessions: 2e3 Protocol: specific (hands) |

sham massage |

Duration: 15 min Frequency**: 2-3 Sessions: 2-3 Type: sham massage |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Braun |

2012 |

75 |

71 |

67 (SD 12) Male: 75% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

Duration: 20 min Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: 2 Protocol: unclear (hands, feet, back, legs, neck, shoulders, head, pt preference) |

standard care |

Duration: 20 min |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Cutshall |

2010 |

30 |

28 |

66 (SD 16) Male: 75% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - body |

Duration: 20 min Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: 1 Protocol: unclear (back, arms, legs, neck, shoulders, head, pt preference) |

standard care with quiet time |

Duration: 20 min |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Kshettry |

2006 |

49 |

50 |

63 (SD 14) Male: 72% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft and/or valve replacement |

Massage - unclear |

Duration: 30 min Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: 1 Protocol: unclear |

standard care with rest period |

Duration: 20 min Frequency**: 1 Sessions: 1 Type: standard care with rest period |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Mitchinson |

2007 |

200 |

202 |

64 (SD 10) Male: 99% |

64% cardiac surgery requiring sternal incision & 36% abdominal surgery |

Massage - back |

Duration: 20 min Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: up to 5 Protocol: specific (back) |

standard of care |

Duration: 20 min Frequency**: 1 Sessions: up to 5 Type: attention control |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Najafi |

2014 |

35 |

35 |

60 (SD 7) Male: 54% |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft |

Massage - body |

Duration: 30 min Frequency/day: 1 Sessions: 1 Protocol: unclear (hands, feet, back, arms, legs, neck, shoulders, pt preference) |

attention control |

Duration: 30 min |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Rejeh |

2013 |

62 |

62 |

65-92y M: 32 |

NS |

Systematic relaxation |

Relaxation therapy repeated 3 times. Post-test measured after 15 min,6h and 12h recovery following ambulation. |

standard of care |

information about their surgery and the current ward protocols regarding ambulation afterwards |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Solehati and Rustina |

2015 |

30 |

30 |

NS F: 60 |

Caesarean |

Benson's relaxation |

Relaxation therapy performed 2 h after the operation, continued twice daily for 4 days. |

standard of care |

regular care as room procedure |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Devi and Saharia |

2017 |

20 |

20 |

20-40y M: 20 |

Appendicectomy, cholecystectomy, hernioplasty, gastrectomy, gastro-jejunostomy |

Progressive muscle relaxation |

For 3 post-operative days, relaxation therapy performed for 15 min. |

NS |

NS |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Ismail and Elgzar |

2018 |

40 |

40 |

20-35y F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Progressive muscle relaxation |

Relaxation therapy performed thrice daily for 30 min on post-operative days 0 and 1. |

NS |

NS |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Degirmen |

2010 |

50 |

25 |

27.3 ± 4.77 F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand and or foot |

20 minutes' massage include petrissage, kneading and friction; the foot massage group received 10 minutes' massage. The massage intervention was applied 2.5 ± 1.0 hours after the administration of analgesics in the intervention groups. |

standard of care |

NS |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Hanan |

2011 |

75 |

75 |

NS F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

foot and hand massage for 20 minutes, 5 minutes for each hand then 5 minutes for each foot. The massage was applied 3 times at 5:40, 11:40, 17:40 hour after delivery. |

standard of care |

NS |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Irani |

2015 |

40 |

40 |

29.25±4.78 and 29.35±4.88 F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

massage was performed for 20 minutes on participant’s extremities (5 minutes for each). The main specialised massage techniques included rotational friction movements, stretching, grasping and flexing on different parts of hands and feet from wrist to toes without focusing on a certain point. |

attention |

In the control group, in the other group, the researcher went to the participants’ bedside for 20 minutes, and had an informal chat with them. |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Sharma |

2019 |

30 |

30 |

age 21 to 35 years F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

NS |

|

|

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Varghese |

2014 |

30 |

30 |

NS F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Foot reflexology |

15-minute foot reflexology session at the same time each evening for five consecutive days. |

|

|

|

|

Abbaspoor 2014 |

2014 |

40 |

40 |

18–35 years; F: 100% |

Caesarean |

Massage - hand & foot |

Foot and hand massage included petrissage, kneading, and friction applied to the patients’ hands and feet. Massage initiated 1.5–2 h after spinal anaesthesia medication. Hand massage applied to each hand for 5 min. Foot massage followed |

attention |

Nurse talked to women for 20 min. Analgesics available for both groups |

|

|

Babamohamadi |

2021 |

30 |

30 |

61.58 ± 9.7 M: 51 |

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery |

rhythmic breathing |

Patients were asked to close their eyes in the supine position, inhale through the nose, then hold their breath, and exhale through the mouth, while counting from 1 to 3 in each step. All the patients in the intervention group were trained to focus only on air entry and exit while breathing, and they were asked to perform RB once every five minutes, lasting one minute each time, for 20 minutes (totally four times every 20 minutes) [32]. Supervised by researcher, RB was performed every 12 hours (9 a.m. and 9 p.m.) for 3 consecutive days. |

standard of care |

(opioids, such as morphine) with no additional interventions |

|

|

Boitor |

2019 |

20 |

20 |

NS |

cardiac surgery patients |

Massage - hand |

20-minute hand massage |

standard of care |

standard of care, no addition |

|

|

Eymir |

2021 |

55 |

51 |

I: 68.0 (60.5/ 73.0) M: 26 |

total knee arthroplasty |

progressive muscle relaxation |

The PMR therapy was administered according to the instruction of a PMR audiotape prepared by the Psychologists Association. Patients listened to the PMR audiotape using an audio player with headphones and performed the PMR exercise under the supervision of the physiotherapist to be familiarized with the intervention. POD 1 - 3 for 2 times a day |

standard physiotherapy alone |

During the inpatient period, standard PT was administered to all patients twice daily and lasted approximately 30 min. The same physiotherapist delivered the standard PT or PMR exercise+standard PT in patients’ rooms. After discharge, the same home exercise program was given to all patients to be performed twice daily. The standard post-operative PT and home exercise program were administered according to a standardized protocol |

|

|

Forward |

2015 |

75 |

74 |

38 to 90 years M: 33.9% |

hip replacement or knee replacement |

M-technique; The “M” Technique (M) is a registered method of structured touch; series of gentle, slow, stroking movements done in a set sequence that causes the person being touched (receiver) to experience a greater sense of relaxation; focus on repetitive sequences signals |

M was performed on the hands and the feet for 18 to 20 minutes, with touch equally distributed among available extremities, paralleling the length of the guided imagery audio program and the duration of massage shown to be most effective at anxiety and pain reduction in previously reported studies. The level of pressure rendered in M is always 3 on a scale in which the maximum pressure is 10 as perceived by the recipient |

standard of care |

NS |

|

|

Gavin |

2006 |

31 |

27 |

NS |

lumbar and spinal surgery |

preoperative relaxation training |

NS |

standard preparation alone |

NS |

|

|

Hasanpour-Dehkordi |

2019 |

35 |

35 |

NS M: 52% |

gastrointestinal tract surgery |

Progressive muscle relaxation |

training on the method of Benson's relaxation training. Intervention for 20 minutes, every 6 hours for 2 days, until 2 hours before the operation. |

standard preparation alone |

NS |

|

|

Koraş |

2019 |

85 |

82 |

NS Male: 50 female: 117 |

laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery |

Massage - foot |

1x40 (total 40 min, 20 min for each foot) |

standard of care |

standard of care, no addition |

|

|

Lin |

2012 |

45 |

48 |

71,0 (SD 11,1) y M: 33 (35.5%) |

joint replacement surgery |

breath relaxation and guided imagery tape |

listen to a breath relaxation and guided imagery tape for 20 minutes daily (2x 10 min tape) |

standard of care |

There were no interventions for patients in the control group and, instead, they were encouraged to rest in bed |

|

|

Mizrak Sahin |

2021 |

15 |

15 |

NS |

Gynecologic Surgery |

Massage - unclear |

massage with lavender oil |

standard of care |

standard of care, no addition |

|

|

Sözen |

2020 |

65 |

34 |

51y or older: 47% M: 32.7% |

laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Hand massage (1/2 treatment arms) |

20 minutes; 10 minutes per hand |

standard of care |

standard of care, no addition |

|

|

Sözen |

2020 |

63 |

34 |

51y or older: 47% M: 32.7% |

laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

Foot Massage (1/2 treatment arms) |

20 minutes; 10 minutes per foot |

standard of care |

standard of care, no addition |

|

|

Weekes |

2021 |

74 |

72 |

60±10 years M: 80/146 (55%) |

Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair |

relaxation, breathing exercises |

Patients in the relaxation group |

standard of care |

All patients in the control and relaxation groups received an ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve block with ropiva-caine preoperatively. The nerve block was per-formed in a similar fashion by board-certified anesthesiologists (nonauthors). General anesthesia was used in all patients. Local anesthesia was not used. The use of postoperative intravenous ketorolac was not standardized. Patients in both groups received 10-mg tablets of oxycodone, 12.5 mg of promethazine hydro-chloride, 100 mg of docusate sodium, and a cold therapy shoulder cuff. If oxycodone tablets could not be prescribed, 10-mg hydrocodone tablets were prescribed. Postoperative NSAID and acetaminophen use was not standardized. |

|

|

Xue |

2016 |

47 |

45 |

25.5±3.77y (range 20-35) F: 100% |

Caesarean delivery |

foot massage |

2.5 ± 1 h after administration of analgesics; 20 minutes foot massage |

standard of care |

standard of care, no addition |

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

follow up |

incomplete data |

outcome measure |

timing of result used in summary |

Result intervention group |

Result control group |

Mean difference [95% CI] (unless stated otherwise) |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Albert |

2009 |

NS |

NS |

VAS 0-10, mean diff score |

2 or 3 days since surgery at 1st administration |

3.24 ± 2 |

3.25 ± 2 |

-0.01 [-0.50, 0.48] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Bauer |

2010 |

NS |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

2 days since |

-1,5 ± 2 |

-0,8 ± 1.8 |

-0.70 [-1.40, 0.00] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Boitor |

2015 |

NS |

NS |

FPT 0-10 |

0 days since |

-0.52 ± 1.81 |

0.16 ± 1.57 |

-0.70 [-1.40, 0.00] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Braun |

2012 |

NS |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

3 or 4 days since |

1.4 ± 1.73 |

2 ± 2.11 |

-0.70 [-1.40, 0.00] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Cutshall |

2010 |

NS |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

2 - 5 days since |

-2.3 ± 2.44 |

-0.4 ± 1.45 |

-2.70 [-3.73, -1.67] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Kshettry |

2006 |

NS |

NS |

NRS 0-10 |

2 or 3 days since surgery at 1st administration |

1.3 ± 1.3 |

2.1 ± 2 |

-0.80 [-1.46, -0.14] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Mitchinson |

2007 |

NS |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

1 day since surgery at 1st administration |

-1.1 ± 2 |

-0.3 ± 1.9 |

-0.80 [-1.18, -0.42] |

|

Boitor 2017 |

Najafi |

2014 |

NS |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

3 days since surgery at 1st administration |

7.17±1.71 |

3.25±1.91 |

3.92 [3.07, 4.77] |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Rejeh |

2013 |

up to 12hours after intervention |

NS |

pain score, NS |

12 hours after intervention |

1.88 ± 0.85 |

3.64 ± 0.48 |

-1.76 [-2.00, -1.52] |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Solehati and Rustina |

2015 |

NS |

NS |

pain score, NS |

12 hours after intervention |

4.23 ± 1.04 |

4.27 ± 1.26 |

-0.04 [-0.62, 0.54] |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Devi and Saharia |

2017 |

3 postop days |

NS |

pain score, NS |

1 hour after intervention at postop day 3 |

1.45 ± 0.69 |

2.60 ± 0.88 |

-1.15 [-1.64, -0.66] |

|

Ju, 2019 |

Ismail and Elgzar |

2018 |

3 postop days |

NS |

pain score, VAS |

after 6 sessions, at postop day 3 |

9.050 ± 1.377 |

8.475 ± 1.695 |

0.58 [-0.10, 1.25] |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Degirmen |

2010 |

up to 90 minutes after intervention |

NS |

NRS 0-10 |

90 minutes after intervention |

3.7 ± 1.1992 |

5.2 ± 1.11 |

-1.27 [-1.79, -0.74] |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Hanan |

2011 |

18 hours after delivery |

NS |

NRS 0-10 |

6 hours after delivery |

4.09 ± 1.55 |

6.44 ± 1.90 |

-1.35 [-1.70, -0.99] |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Irani |

2015 |

up to 90 minutes after intervention |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

90 minutes after the massage |

32.60 ± 20 |

48.40 ± 14 |

-0.91 [-1.37, -0.45] |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Sharma |

2019 |

between 48 and 120 hours |

NS |

NS |

Up to 24 hours |

6.03 ± 0.71 |

7.4 ± 0.73 |

-1.88 [-2.49, -1.26] |

|

Zimpel, 2020 |

Varghese |

2014 |

NS |

NS |

NS |

More than 48 up to 120 hours |

4.75 ± 2.4482 |

7.65 ± 3.9429 |

-0.87 [-1.40, -0.34] |

|

|

Abbaspoor 2014 |

2014 |

intervention started 1.5-2 h after spinal medication; measurement 90 min after intervention |

NS |

NRS 0-10 |

90 minutes after intervention; intervention 1.5-2 h after spinal medication. |

3.54 ± 0.64 |

6.23 ± 0.68 |

-2.69 [-2.98, -2.40] |

|

|

Babamohamadi |

2021 |

third day after intervention |

in both groups 2 patients (2/32) were lost to FU during the 3 days intervention |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

second day after the intervention, 9 a.m. |

1.90 ± 0.54 |

2 ± 1.23 |

-0.10 [-0.58, 0.38] |

|

|

Boitor |

2019 |

24h |

substantial missing data |

NRS 0-10 |

second postoperative day |

median 0 [IQR 0-7] |

median 2 [IQR 0-4.5] |

median diff: -2 |

|

|

Eymir |

2021 |

postop third day |

I: 1 lost to FU |

pain score, NPRS Numeric Pain Rating |

Postop 2nd day |

median 3.0 (IQR 2.0 - 4.0) |

median 3.0 (IQR 2.0 - 5.0) |

median diff: 0 |

|

|

Forward |

2015 |

2 postop days |

none reported |

Numeric Visual Anxiety Scale (NVAS), Pain Numeric Rating Scale (PNRS) |

Postoperative day 1 |

2.6 (SD not provided) |

3.6 (SD not provided) |

-1.0 |

|

|

Gavin |

2006 |

2 postop days |

I: 5/27 |

verbal pain score (0-10) controlled for PACU narcotic use |

postop day 1 |

4.8 ± 1.7; Cl,1.5-8.1; N=22 |

3.9 ± 1.7; CI,0.6-7.2; N=18 |

0.90 [-0.16, 1.96] |

|

|

Hasanpour-Dehkordi |

2019 |

24 hours |

none reported |

Bayer numerical scale, pain; 0 – 10 presented in 4 categories of pain severity (unclear how categories were created) |

24 hours |

Very low 77% |

Very low 65% |

|

|

|

Koraş |

2019 |

120 min after intervention; |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

120 minutes after intervention |

1.26 ± 1.15 |

3.60 ± 1.41 |

-2.34 [-2.73, -1.95] |

|

|

Lin |

2012 |

postop third day |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10; |

Postop 2nd day |

1.04 ± 1.33 |

0.60 ± 1.42 |

0.44 [-0.12, 1.00] |

|

|

Mizrak Sahin |

2021 |

Massage application was performed 3 hours after analgesic application; measurement 30 min & 3h after massage |

NS |

VRS 0-10 |

3rd h after the massage |

3.06 ± 1.27 |

3.40 ± 1.50 |

-0.34 [-1.33, 0.65] |

|

|

Sözen (hand) |

2020 |

150 minutes after massage |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

150 minutes after massage |

1.61 ± 1.40 |

3.44 ± 1.43 |

-1.83 [-2.42, -1.24] |

|

|

Sözen (foot) |

2020 |

150 minutes after massage |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

150 minutes after massage |

1.43 ± 1.20 |

3.44 ± 1.43 |

-2.01 [-2.57, -1.45] |

|

|

Weekes |

2021 |

5 days postoperatively |

I: 15/74 not included in analysis |

pain at rest VAS score |

Postoperative day 1 |

5 ± 3 |

6 ± 3 |

-1.00 [-1.97, -0.03] |

|

|

Xue |

2016 |

60 minutes after massage |

NS |

NRS 0-10 |

60 minutes after massage |

2.54 ± 1.22 |

5.07 ± 1.45 |

-2.53 [-3.08, -1.98] |

Communication and therapeutic suggestion

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

N INT |

N CNTL |

Age Sex |

Surgery |

Intervention |

Regime |

Control |

Regime |

|

|

Gonzales |

2010 |

22 |

22 |

I: 35.91 ± 15.13

M: 13/22 |

same-day surgical procedures |

Guided imagery |

This CD led the patient through a progressive relaxation and guided imagery exercise. (.) This CD consisted of |

usual care |

NS |

|

|

Forward |

2015 |

75 |

74 |

aged 38 to 90 years

M: 33.9% |

hip replacement or knee replacement |

Guided imagery |

The guided imagery program selected was Guided Meditation for Procedures or Surgery, created by Diane Tusek. This selection was based on |

usual care |

NS |

|

|

Shah |

2021 |

16 |

16 |

median 57 (IQR 54-63) y F: 100% |

vaginal hysterectomy with minimally invasive sacrocolpopexy |

therapeutic suggestion |

therapeutic suggestions per protocol; |

usual care |

NS |

|

|

Nowak |

2020 |

191 |

194 |

Median (interquartile range) age (years)

Female I: 115/191 (60%) |

surgery for 1-3 hours under general anaesthesia |

audiotape of background music and positive suggestions |

played repeatedly for 20 minutes followed by 10 minutes of silence to patients through earphones during general anaesthesia |

blank tape |

same regime as intervention, but blank tape |

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

follow up |

incomplete data |

outcome measure |

timing of result used in summary |

Results intervention group |

Result control group |

Mean difference [95% CI] (unless stated otherwise) |

|

Posadzki, 2012 |

Gonzales |

2010 |

2-hour FU |

NS |

pain score; v(vertical)VAS 0-100 |

in ambulatory procedure unit (PACU length of stay on average for control group and intervention group 43 ± 20 and 34 ±10 minutes, and stay in APU 103 ±44 and 103 ±55 resp. |

20.00 ± 28.92 |

34.72 ± 27.54 |

-14.72 [-31.41, 1.97] |

|

|

Forward |

2015 |

2 postop days |

none reported |

Numeric Visual Anxiety Scale (NVAS), Pain Numeric Rating Scale (PNRS) |

postop day 1 |

2.9 (SD onbekend) |

3.5 (SD onbekend) |

MD 0.6; |

|

|

Shah 2021 |

2021 |

2 weeks |

NS |

VAS 0-10 |

24 h |

median 4 (3-5) |

median 4 (3-5) |

Median diff 0 |

|

|

Nowak |

2020 |

postoperative 24 hours |

NS |

NRS 0-10 |

24 hours (asked for maximum pain scores in 24h period) |

median 4 (IQR 3-6) |

median 5 (IQR 4-7) |

Median diff 1 |

Virtual reality

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

N INT |

N CNTL |

Age Sex |

Surgery |

Intervention |

Regime |

Control |

Regime |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Bekelis |

2017 |

64 |

63 |

55.3 ± 14.0 NS |

Craniotomy/ spine surgery |

Virtual reality |

Watching a 5-min video through the VR glasses which describes the operative experience; 5min (not available), Before the surgery |

Provided with routine audiovisual descriptions of the operative experience |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Ding |

2019 |

91 |

91 |

45.8 ± 12.6 NS |

Hemorrhoi-dectomy |

Virtual reality |

VR distraction through the VR glasses plus standard pharmacological analgesic intervention; 20–30min (1/d), After the surgery |

Standard pharmacological analgesic intervention |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Jahanishoorab |

2015 |

15 |

15 |

24.1 ± 4.1 NS |

Episiotomy repair |

Virtual reality |

VR distraction the VR glasses plus pharmacological anesthesia; 30min (1/d), during the surgery |

Pharmacological anesthesia |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Jin |

2018 |

33 |

33 |

I:66.45 ± 3.49 NS |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Receiving the rehabilitation in the immersive virtual environment through the VR glasses plus conventional; 30min (3/d), after the surgery |

Conventional rehabilitation protocol |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Li |

2018 |

39 |

39 |

71.82 ± 7.98 C: 72.97 ± 7.82 NS |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Receiving the rehabilitation in the immersive virtual environment through the VR glasses plus conventional rehabilitation protocol; 30min (3/d) After the surgery |

Conventional rehabilitation protocol |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Piqueras |

2013 |

72 |

70 |

73.3 ± 6.5 NS |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Receiving rehabilitation through an interactive virtual software platform which has a 3D avatar that shows the exercises to be undertaken; 60min (1/d) After the surgery |

Receiving the standard clinical protocol of rehabilitation |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Sweta |

2019 |

25 |

25 |

39.72 ± 15.93 NS |

Dental surgery |

Virtual reality |

VR distraction through the VR glasses plus local anesthesia; NS, During the surgery |

Local anesthesia |

NS |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Yang |

2019 |

24 |

24 |

I:32.5 (15.0–62.0) NS |

Knee surgery |

Virtual reality |

Watching a 3D model of their own MRIs through the VR glasses; 20–30min (1/d) Before the surgery |

Receiving standard preoperative information about their MRIs through a picturearchiving and communications system |

NS |

|

|

Gianola |

2020 |

44 |

41 |

68.6 (±8.8) y68.6 (±8.8) y F: 48/85 (56.5% |

total knee arthroplasty |

Virtual reality |

VR via the Virtual Reality Rehabilitation System (VRRS); passive knee motion on a Kinetec knee continuous passive motion system (Rimec, Chions, Italy) and functional exercises (stair negotiation and level walking) daily for 60 minutes on at least 5 days |

traditional rehabilitation, providing the same exercises without VR |

passive knee motion on a Kinetec knee continuous passive motion system (Rimec, Chions, Italy) and functional exercises (stair negotiation and level walking) daily for 60 minutes on at least 5 days |

|

Review (if applicable) |

Author |

Year |

follow up |

incomplete data |

outcome measure |

Results intervention group |

Result control group |

Mean difference [95% CI] (unless stated otherwise) |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Bekelis |

2017 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

3.02 ± 1.25 |

3.03 ± 0.75 |

-0.01 [-0.37. 0.35] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Ding |

2019 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

4.09 ± 13.55 |

4.17 ± 12.5 |

-0.08 [-3.87. 3.71] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Jahanishoorab |

2015 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; NRS 0-10 |

0.6 ± 1.28 |

2.52 ± 1.4 |

-1.92 [-2.88. -0.96] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Jin |

2018 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

6.48 ± 0.87 |

6.84 ± 1.09 |

-0.36 [-0.84. 0.12] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Li |

2018 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

2.54 ± 0.69 |

3.1 ± 0.96 |

-0.56 [-0.93. -0.19] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Piqueras |

2013 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

3.11 ± 1.79 |

3.69 ± 1.9 |

-0.58 [-1.19. 0.03] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Sweta |

2019 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

1.28 ± 0.891 |

2.6 ± 1.38 |

-1.32 [-1.96. -0.68] |

|

Ding, 2020 |

Yang |

2019 |

NS |

NS |

pain score; VAS 0-10 |

3.03 ± 2.88 |

3.02 ± 2.84 |

0.01 [-1.61. 1.63] |

|

|

Gianola |

2020 |

3-4 days after surgery |

NS |

VAS pain difference score (0-100) |

-23.03 (95% CI -0.26 to -15.79) |

-28.97 (95% CI -36.82 to -1.12) |

NS |

Risk of bias tables

The following 7 criteria were assessed: Random sequence generation (selection bias)

- Allocation concealment (selection bias)

- Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias): All outcomes

- Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): All outcomes

- Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias): All outcomes

- Selective reporting (reporting bias)

- Other bias

Risk of bias is indicated by colours: green: Low risk of bias; yellow: Unclear risk of bias; red: High risk of bias

Massage and relaxation

Communication and therapeutic suggestion

Virtual reality

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Gorsky K, Black ND, Niazi A, Saripella A, Englesakis M, Leroux T, Chung F, Niazi AU. Psychological interventions to reduce postoperative pain and opioid consumption: a narrative review of literature. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021 Oct;46(10):893-903. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2020-102434. Epub 2021 May 25. PMID: 34035150. |

Design |

|

Szeverenyi C, Kekecs Z, Johnson A, Elkins G, Csernatony Z, Varga K. The Use of Adjunct Psychosocial Interventions Can Decrease Postoperative Pain and Improve the Quality of Clinical Care in Orthopedic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Pain. 2018 Nov;19(11):1231-1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.05.006. Epub 2018 May 25. PMID: 29803669. |

does not meet PICO (I,C,O) |

|

Sears SR, Bolton S, Bell KL. Evaluation of "Steps to Surgical Success" (STEPS): a holistic perioperative medicine program to manage pain and anxiety related to surgery. Holist Nurs Pract. 2013 Nov-Dec;27(6):349-57. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0b013e3182a72c5a. PMID: 24121700. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Fu D, Yang J, Zhu R, Pan Q, Shen X, Peng Y. Guo, X. R.; Wang, F. Z. Preoperative psychoprophylactic visiting alleviates maternal anxiety and stress and improves outcomes of cesarean patients: A randomized, double-blind and controlled trial. Healthmed 2012; 6(1):263-277. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Good M, Albert JM, Anderson GC, Wotman S, Cong X, Lane D, Ahn S. Supplementing relaxation and music for pain after surgery. Nurs Res. 2010 Jul-Aug;59(4):259-69. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbb2b3. PMID: 20585222. |

does not meet PICO (O) |

|

Gündüz CS, Çalişkan N. The Effect of Preoperative Video Based Pain Training on Postoperative Pain and Analgesic Use in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Non-randomized Control Group Intervention Study. Clin Nurs Res. 2021 Jul;30(6):741-752. doi: 10.1177/1054773820983361. Epub 2020 Dec 31. PMID: 33383995. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Rejeh N, Heravi-Karimooi M, Vaismoradi M, Jasper M. Effect of systematic relaxation techniques on anxiety and pain in older patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Int J Nurs Pract. 2013 Oct;19(5):462-70. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12088. Epub 2013 May 28. PMID: 24093737. |

include in SR |

|

Cizmic Z, Edusei E, Anoushiravani AA, Zuckerman J, Ruden R, Schwarzkopf R. The Effect of Psychosensory Therapy on Short-term Outcomes of Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Orthopedics. 2018 Nov 1;41(6):e848-e853. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20181010-04. Epub 2018 Oct 16. PMID: 30321440. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Posadzki P, Lewandowski W, Terry R, Ernst E, Stearns A. Guided imagery for non-musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012 Jul;44(1):95-104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.07.014. Epub 2012 Jun 5. PMID: 22672919. |

relevant studies included individually |

|

Faruki A, Nguyen T, Proeschel S, Levy N, Yu J, Ip V, Mueller A, Banner-Goodspeed V, O'Gara B. Virtual reality as an adjunct to anesthesia in the operating room. Trials. 2019 Dec 27;20(1):782. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3922-2. PMID: 31882015; PMCID: PMC6935058. |

study protocol |

|

Antall GF, Kresevic D. The use of guided imagery to manage pain in an elderly orthopaedic population. Orthop Nurs. 2004 Sep-Oct;23(5):335-40. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200409000-00012. PMID: 15554471. |

N < 10 |

|

Ding J, He Y, Chen L, Zhu B, Cai Q, Chen K, Liu G. Virtual reality distraction decreases pain during daily dressing changes following haemorrhoid surgery. J Int Med Res. 2019 Sep;47(9):4380-4388. doi: 10.1177/0300060519857862. Epub 2019 Jul 25. PMID: 31342823; PMCID: PMC6753557. |

include in SR |

|

Huang MY, Scharf S, Chan PY. Effects of immersive virtual reality therapy on intravenous patient-controlled sedation during orthopaedic surgery under regional anesthesia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2020 Feb 24;15(2):e0229320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229320. PMID: 32092098; PMCID: PMC7039521. |

does not meet PICO (O) |

|

Laghlam D, Naudin C, Coroyer L, Aidan V, Malvy J, Rahoual G, Estagnasié P, Squara P. Virtual reality vs. Kalinox® for management of pain in intensive care unit after cardiac surgery: a randomized study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021 May 13;11(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00866-w. PMID: 33983498; PMCID: PMC8119554. |

does not meet PICO (O) |

|

Chooi CS, White AM, Tan SG, Dowling K, Cyna AM. Pain vs comfort scores after Caesarean section: a randomized trial. Br J Anaesth. 2013 May;110(5):780-7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes517. Epub 2013 Feb 5. PMID: 23384734. |

does not meet PICO (I, C) |

|

Chuang CC, Lee CC, Wang LK, Lin BS, Wu WJ, Ho CH, Chen JY. An innovative nonpharmacological intervention combined with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia increased patient global improvement in pain and satisfaction after major surgery. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017 Apr 6;13:1033-1042. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S131517. PMID: 28435273; PMCID: PMC5388275. |

study design |

|

Tian Y, Lin J, Gao F. The effects of comfort care on the recovery quality of oral and maxillofacial surgery patients undergoing general anesthesia. Am J Transl Res. 2021 May 15;13(5):5003-5010. PMID: 34150085; PMCID: PMC8205744. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Grafton-Clarke C, Grace L, Roberts N, Harky A. Can postoperative massage therapy reduce pain and anxiety in cardiac surgery patients? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2019 May 1;28(5):716-721. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy310. PMID: 30508186. |

Design |

|

Meena S. ASSESS THE EFFECTIVENESS OF HAND AND FOOT MASSAGE IN REDUCING POSTOPERATIVE PAIN AMONG ABDOMINAL SURGERY PATIENTS. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2019, 10 (4). DOI: 10.7897/2230-8407.1004137 |

Low quality; does not report findings of control group |

|

Miller J, Dunion A, Dunn N, Fitzmaurice C, Gamboa M, Myers S, Novak P, Poole J, Rice K, Riley C, Sandberg R, Taylor D, Gilmore L. Effect of a Brief Massage on Pain, Anxiety, and Satisfaction With Pain Management in Postoperative Orthopaedic Patients. Orthop Nurs. 2015 Jul-Aug;34(4):227-34. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000163. PMID: 26213879. |

Crossover design without seperated result section |

|

Mitchinson AR, Kim HM, Geisser M, Rosenberg JM, Hinshaw DB. Social connectedness and patient recovery after major operations. J Am Coll Surg. 2008 Feb;206(2):292-300. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.08.017. Epub 2007 Nov 12. PMID: 18222382. |

Does not meet PICO (I, C, O) |

|

Rosen J, Lawrence R, Bouchard M, Doros G, Gardiner P, Saper R. Massage for perioperative pain and anxiety in placement of vascular access devices. Adv Mind Body Med. 2013 Winter;27(1):12-23. PMID: 23341418. |

Results on pain not available per treatment group |

|

Boitor M, Martorella G, Laizner AM, Maheu C, Gélinas C. The Effectiveness of Hand Massage on Pain in Critically Ill Patients After Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016 Nov 7;5(4):e203. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6277. PMID: 27821384; PMCID: PMC5118583. |

trial protocol |

|

Bauer BA, Cutshall SM, Wentworth LJ, Engen D, Messner PK, Wood CM, Brekke KM, Kelly RF, Sundt TM 3rd. Effect of massage therapy on pain, anxiety, and tension after cardiac surgery: a randomized study. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010 May;16(2):70-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.06.012. Epub 2009 Jul 14. PMID: 20347836. |

included in SR; Boitor 2017 |

|

Boitor M, Martorella G, Arbour C, Michaud C, Gélinas C. Evaluation of the preliminary effectiveness of hand massage therapy on postoperative pain of adults in the intensive care unit after cardiac surgery: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015 Jun;16(3):354-66. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.08.014. PMID: 26025795. |

included in SR; Boitor 2017 |

|

Hui X, Bingxin K, Chenxin G, Chi Z, Xirui X, Songtao S, Jun X, Lianbo X, Qi S. Effectiveness of Tuina in the treatment of pain after total knee arthroplasty in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Chinese Journal of Tissue Engineering Research ›› 2021, Vol. 25 ›› Issue (18): 2840-2845.doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4344.3845

|

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Midilli TS, Eser I. Effects of Reiki on Post-cesarean Delivery Pain, Anxiety, and Hemodynamic Parameters: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015 Jun;16(3):388-99. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2014.09.005. PMID: 26025798. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Mitchinson AR, Kim HM, Rosenberg JM, Geisser M, Kirsh M, Cikrit D, Hinshaw DB. Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2007 Dec;142(12):1158-67; discussion 1167. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1158. PMID: 18086982. |

included in SR; Boitor 2017 |

|

Najafi SS, Rast F, Momennasab M, Ghazinoor M, Dehghanrad F, Mousavizadeh SA. The effect of massage therapy by patients' companions on severity of pain in the patients undergoing post coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2014 Jul;2(3):128-35. PMID: 25349854; PMCID: PMC4201205. |

included in SR; Boitor 2017 |

|

Sagkal Midilli T, Ciray Gunduzoglu N. Effects of Reiki on Pain and Vital Signs When Applied to the Incision Area of the Body After Cesarean Section Surgery: A Single-Blinded, Randomized, Double-Controlled Study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2016 Nov/Dec;30(6):368-378. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000172. PMID: 27763932. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Shaybak E, Abdollahimohammad A, Rahnama M, Masinaeinezhad N, Azadi-Ahmadabadi C, Firouzkohi M. The effect of reiki energy healing on CABG postoperative chest pain caused by coughing and deep breathing. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development 2017; Volume 8, Issue 2, April-June, Pages 305-310 |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Simonelli MC, Doyle LT, Columbia M, Wells PD, Benson KV, Lee CS. Effects of Connective Tissue Massage on Pain in Primiparous Women After Cesarean Birth. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2018 Sep;47(5):591-601. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2018.07.006. Epub 2018 Aug 11. PMID: 30102886. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Attias S, Sivan K, Avneri O, Sagee A, Ben-Arye E, Grinberg O, Sroka G, Matter I, Schiff E. Analgesic Effects of Reflexology in Patients Undergoing Surgical Procedures: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2018 Aug;24(8):809-815. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0167. Epub 2018 Jun 8. PMID: 29883188. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Khorsand A, Tadayonfar MA, Badiee S, Aghaee MA, Azizi H, Baghani S. Evaluation of the Effect of Reflexology on Pain Control and Analgesic Consumption After Appendectomy. J Altern Complement Med. 2015 Dec;21(12):774-80. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0270. Epub 2015 Sep 24. PMID: 26401598. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Tsay SL, Chen HL, Chen SC, Lin HR, Lin KC. Effects of reflexotherapy on acute postoperative pain and anxiety among patients with digestive cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008 Mar-Apr;31(2):109-15. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305694.74754.7b. PMID: 18490886. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Mohammadi S, Pouladi S, Ostovar, A, Ravanipour M.. Effects of foot reflexology massage on pain and fatigue in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 2018; 8, 0, S513 |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Haase O, Schwenk W, Hermann C, Müller JM. Guided imagery and relaxation in conventional colorectal resections: a randomized, controlled, partially blinded trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005 Oct;48(10):1955-63. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0114-9. PMID: 15991068. |

no description of relevant outcome |

|

Good M, Albert JM, Arafah B, Anderson GC, Wotman S, Cong X, Lane D, Ahn S. Effects on postoperative salivary cortisol of relaxation/music and patient teaching about pain management. Biol Res Nurs. 2013 Jul;15(3):318-29. doi: 10.1177/1099800411431301. Epub 2012 Apr 3. PMID: 22472905. |

does not meet PICO (C) |

|

Mehling WE, Jacobs B, Acree M, Wilson L, Bostrom A, West J, Acquah J, Burns B, Chapman J, Hecht FM. Symptom management with massage and acupuncture in postoperative cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007 Mar;33(3):258-66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.016. PMID: 17349495. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Weston E, Raker C, Huang D, Parker A, Robison K, Mathews C. The Association Between Mindfulness and Postoperative Pain: A Prospective Cohort Study of Gynecologic Oncology Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Jul-Aug;27(5):1119-1126.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.08.021. Epub 2019 Aug 23. PMID: 31449907. |

study design |

|

Hadi N, Hanid AA. Lavender essence for post-cesarean pain. Pak J Biol Sci. 2011 Jun 1;14(11):664-7. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2011.664.667. PMID: 22235509. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Kim JT, Ren CJ, Fielding GA, Pitti A, Kasumi T, Wajda M, Lebovits A, Bekker A. Treatment with lavender aromatherapy in the post-anesthesia care unit reduces opioid requirements of morbidly obese patients undergoing laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2007 Jul;17(7):920-5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9170-7. PMID: 17894152. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Kim JT, Wajda M, Cuff G, Serota D, Schlame M, Axelrod DM, Guth AA, Bekker AY. Evaluation of aromatherapy in treating postoperative pain: pilot study. Pain Pract. 2006 Dec;6(4):273-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00095.x. PMID: 17129308. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Marzouk T, Barakat R, Ragab A, Badria F, Badawy A. Lavender-thymol as a new topical aromatherapy preparation for episiotomy: A randomised clinical trial. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;35(5):472-5. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2014.970522. PMID: 25384116. |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Najafi B, Fariba F, Daem R, Ghaderi L, Seidi J. The effect of lavender essence on pain severity after cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. Journal of chemical and pharmaceutical sciences, 2016, 2016, 66‐69 |

does not meet PICO (I) |

|

Nazari M, Kamrani F, Sahebalzamani M, Amin, GR. On the investigation of the effect of aromatherapy on pain after orthopedic surgery: clinical trial. Acta Medica Mediterranea, 2016, 32: 1513 |