Magnesium

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de meerwaarde van de toevoeging van perioperatief magnesium bij patiënten die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg de toediening van magnesium intraveneus bij hemodynamisch stabiele patiënten.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar de effectiviteit van perioperatief magnesium vergeleken met standaardzorg bij patiënten die een chirurgische ingreep ondergingen. Postoperatieve pijn was de cruciale uitkomstmaat en het postoperatieve gebruik van opioïden en adverse events waren de belangrijke uitkomstmaten voor klinische besluitvorming.

Omdat de systematic review van Ng (2020) het uitgangspunt was, kon de werkgroep alleen conclusies trekken over de uitkomstmaten die zij rapporteerden. Dat waren postoperatieve pijn op 24 uur, postoperatief opiaatgebruik in 24 uur en bradycardie.

De bewijskracht voor pijnscores op 24 uur postoperatief is redelijk. Er is alleen afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias. Er werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden tussen de groepen.

Voor het effect van magnesium op postoperatief opioïdengebruik is een redelijke bewijskracht gevonden voor 24 uur postoperatief, maar weer was het effect niet klinisch relevant.

In een eerdere systematische review van Murphy (2013) werd beschreven dat er bij de gepoolde pijnscores op 4-6 uur postoperatief een groter pijnstillend effect was dan 20-24 uur postoperatief met een gewogen gemiddeld verschil van -0,67 (-1,12 tot -0,23).

Ook werd het verschil in pijnscores en opioïdengebruik separaat als niet klinisch relevant beoordeeld, zo wijst toch de combinatie van een vermindering van pijnscores > 0,5 en een vermindering van opioïdengebruik > 5 mg op een aanwezig analgetisch effect.

De bewijskracht van het effect van magnesium op bradycardie is laag (GRADE), omdat er studies werden geïncludeerd met weinig patiënten en weinig events. Daarnaast was er ook risico op bias. Dit maakt het effect op bradycardie onzeker. De gemiddelde stijging in postoperatieve magnesiumspiegels lijkt beperkt (+0.59 mmol/L) na toediening van magnesium. Het is daardoor te verwachten dat het risico op bradycardie zal meevallen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is het belangrijk om adequate postoperatieve pijnstilling te hebben met zo min mogelijk complicaties. De voorkeur gaat ernaar uit om het gebruik van opioïden zoveel mogelijk te beperken. Magnesium lijkt in multimodale analgesie het gebruik van opiaten iets terug te kunnen dringen, maar het verschil bereikt de grens voor klinische relevantie niet. Er is een mogelijk beperkt toegenomen risico op bradycardie. Daar staat tegenover dat magnesium een geneesmiddel is dat reeds wordt toegediend op de operatiekamer en de werking geantagoneerd kan worden door calciumgluconaat.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De algehele kosteneffectiviteit van magnesium zijn nog niet in kaart gebracht. Uitgaande van het gebruik van spuitenpompen zal de tijd van klaarmaken van een extra middel beperkt zijn. Magnesiumsulfaat is een middel dat reeds op de operatiekamer wordt toegediend. Er is daardoor geen extra scholing of kwalificatie van personeel nodig. Als er minder opioïden perioperatief kort postoperatief gegeven worden, zal dat administratietijd schelen die verbonden is aan de opiumwetgeving. Waarschijnlijk zal de implementatie van magnesiumsulfaat tot een vergelijkbare perioperatieve tijdsbesteding hebben.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen procesevaluatie gedaan die de implementatie van magnesiumsulfaat in de Nederlandse setting beschrijft. Daarentegen zijn er meer dan vijftig studies gedaan naar magnesiumsulfaat intra-operatief. Hieruit kan afgeleid worden dat de toepassing haalbaar moet zijn. Bovendien wordt magnesiumsulfaat intraveneus al reeds toegepast op de operatiekamers.

Een bezwaar zou zijn dat magnesium kan leiden tot hemodynamische instabiliteit. Het risico lijkt uit de literatuur zeer beperkt, hoewel de evidence hiervoor niet groot is. Omdat niet onderzocht is bij hemodynamisch instabiele patiënten is het advies om terughoudend te zijn om magnesiumsulfaat toe te passen bij kwetsbare patiënten.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Magnesium intraveneus geeft in aanvulling op de standaardanesthesie een lichte reductie op pijnscores. De hoeveelheid gebruikte opioïden die benodigd is gedurende 24 uur of gehele postoperatieve periode lijkt licht af te nemen. Vanwege dit gecombineerde effect is magnesium te overwegen ten behoeve van postoperatieve pijnstilling. Het effect van magnesium als mono-interventie zal echter beperkt zijn. Er zijn geen verschillen gevonden in het effect op bradycardie, maar gezien er potentieel een effect zou kunnen zijn, is er enige terughoudendheid geboden bij hemodynamische instabiele patiënten.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Multidomale pijnbestrijding wordt gezien als perioperatieve standaardzorg. Verschillende niet-opioïden worden hiervoor gebruikt, waaronder magnesium. Magnesium kan via het effect op de NDMA-receptor de pijnstilling van andere nociceptieve stoffen vergroten. Het is belangrijk om de positieve analgetische effecten van magnesium af te wegen tegen mogelijke hemodynamische bijwerkingen zoals bradycardie en ECG-afwijkingen.

Conclusies

Postoperative pain

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of perioperative magnesium on pain scores at PACU arrival, at 6 hours, at 12 hours, and 48 post-surgery when compared to standard care in surgical patients.

Source: - |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Perioperative magnesium likely does not reduce pain scores at 24 hours post-surgery when compared to standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Benevides, 2021; Dehkordy, 2020; Kayalha, 2019; Lu, 2021; Mahajan, 2019; Ng, 2020; Sohn, 2021; Yazdi, 2022. |

Postoperative opioid consumption

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of perioperative magnesium on postoperative opioid consumption in PACU and in the total postoperative period when compared to standard care in surgical patients.

Sources: - |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Perioperative magnesium likely does not reduce postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours when compared to standard care in surgical patients.

Sources: Dehkordy, 2020; El Mourad, 2019; Farouk, 2021; Kayalha, 2019; Mahajan, 2019; Ng, 2020; Sohn, 2021; Tsaousi, 2020; Yazdi, 2022. |

Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Perioperative magnesium may not increase the incidence of bradycardia compared to standard care in surgical patients.

Sources: Dehkordy, 2020; El Mourad, 2019; Gao, 2020; Kim, 2021; Lu, 2021; Ng, 2020; Tsaousi, 2020. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

As shown in table 1, different regimens were used in various surgeries and using different scales to assess postoperative pain. All studies were RCTs.

Ng (2020) included studies administering intravenous magnesium (perioperative) and placebo in adult patients undergoing any type of noncardiac surgery. A total of 52 RCTs with

3341 patients were included in Ng (2020) for qualitative analysis. Out of these RCTs, 35 were conform the PICO and thus included in this literature analysis.

There was a wide range in the applied doses of magnesium among the studies. The majority of the studies applied a bolus dosing based on weight, of which most of the studies were followed by a continuous infusion. One study did not mention the used dose (Mireskandari 2015).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies that compared magnesium with standard of care.

|

Author, year |

Intervention |

Control |

Surgery type |

N total |

||||

|

bolus |

infusion |

|||||||

|

Studies from Ng, 2020 |

||||||||

|

Ahmed 2018 |

50 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Thoracic surgery |

60 |

|||

|

Ayoglu 2005 |

50 mg/kg |

8 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Abdominal surgery |

40 |

|||

|

Benhaj Amor 2008 |

50 mg/kg |

500 mg/h |

n.s. |

Open cholecystectomy, |

48 |

|||

|

Bhatia 2004 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Open cholecystectomy |

50 |

|||

|

Cizmeci 2007 |

50 mg/kg |

8 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Septorhinoplasty |

60 |

|||

|

Dabbagh 2009 |

- |

8 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Lower limb orthopaedic surgery |

60 |

|||

|

Demiroglu 2016 |

50 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Lumbar disc surgery |

50 |

|||

|

Elsersy 2017 |

- |

30 mg/kg/1h, then 9 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Functional endoscopy surgery |

294 |

|||

|

Frassanito 2015 |

40 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Total knee amputation |

40 |

|||

|

Gozdemir 2010 |

80 mg/kg |

2 g/h |

n.s. |

Transurethral prostatectomy |

60 |

|||

|

Haryalchi 2017 |

- |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Total abdominal hysterectomy |

40 |

|||

|

Hwang 2010 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Total hip arthroplasty |

40 |

|||

|

Ibrahim 2014 |

50 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Lower extraperitoneal and lower limb surgery |

80 |

|||

|

Jaoua 2010 |

50 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Gastrointestinal surgery |

38 |

|||

|

Kaya 2009 |

30 mg/kg |

500 mg/h |

n.s. |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

40 |

|||

|

Kim 2015 |

50 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Endoscopic submucosal |

60 |

|||

|

Kiran 2011 |

50 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Inguinal surgery |

100 |

|||

|

Kizilcik 2018 |

30 mg/kg |

20 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Sleeve gastrectomy |

80 |

|||

|

Ko 2011 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

58 |

|||

|

Kocman 2013 |

- |

5 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Elective subumbilical surgery |

60 |

|||

|

Kumar 2013 |

50 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

60 |

|||

|

Mireskandari 2015 |

50 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Caesarean section |

50 |

|||

|

Muthiah 2016 |

- |

150 mg/h |

n.s. |

Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament repair |

40 |

|||

|

Oguzhan 2008 |

30 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Lumbar orthopaedic surgery |

50 |

|||

|

Olgun 2012 |

40 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

60 |

|||

|

Ryu 2016 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Laparoscopic gastrectomy |

74 |

|||

|

Seyhan 2006 |

40 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h, 20 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Total abdominal hysterectomy |

60 |

|||

|

Shin 2016 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Bilateral total knee amputation |

44 |

|||

|

Sohn 2017 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Thoracoscopic surgery |

62 |

|||

|

Song 2011 |

30 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Thyroidectomy |

84 |

|||

|

Sousa 2016 |

20 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Laparoscopic gynaecological |

36 |

|||

|

Taheri 2015 |

50 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

40 |

|||

|

Walia 2018 |

30 mg/kg |

- |

n.s. |

Elective surgery |

80 |

|||

|

Wilder-Smith 1997 |

200 mg |

200 mg/h |

n.s. |

Hysterectomy |

24 |

|||

|

Zarauza 2000 |

30 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

n.s. |

Colorectal surgery |

92 |

|||

|

Additional RCTs |

||||||||

|

Author, year |

Intervention |

Control |

Surgery type |

Start of infusion |

End of infusion |

N total |

||

|

bolus |

infusion |

|||||||

|

Benevides 2021 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

Before anesthesia |

End of surgery |

92 |

|

|

Dehkordy 2020 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Posterior lumbar spinal fusion surgery |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

80 |

|

|

El Mourad 2019 |

30 mg/kg |

- |

Placebo |

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy |

Before dissection |

n.a. |

80 |

|

|

Farouk 2021 |

- |

15 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Bilateral inguinal hernial surgery |

Before anesthesia |

End of surgery |

40 |

|

|

Gao 2020 |

50 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Hysteroscopy |

Before anesthesia |

End of surgery |

70 |

|

|

Kayalha 2019 |

5 mg/kg |

|

Placebo |

Femur or hip fracture surgery |

After block |

n.a. |

60 |

|

|

Kim 2021 |

50 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Elective robotic radical prostatectomy |

Before anesthesia |

End of surgery |

60 |

|

|

Lu 2021 |

20 mg/kg |

20 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

10 min before intubation |

End of surgery |

90 |

|

|

Mahajan 2019 |

50 mg/kg |

25 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Elective craniotomy |

‘intra-operative’ |

‘intraoperative’ |

45 |

|

|

Moon 2020 |

40 mg/kg |

10 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Laparoscopic gynaecological |

Before anesthesia |

End of surgery |

132 |

|

|

Sohn 2021 |

30 mg/kg |

15 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Major spine surgery |

After intubation |

End of surgery |

72 |

|

|

Tsaousi 2020 |

20 mg/kg |

20 mg/kg/h |

Placebo |

Single-space lumbar spine laminectomy |

Before anesthesia |

End of surgery |

74 |

|

|

Yazdi 2022 |

- |

25 mg/kg/1h, then 100 mg/kg/24 h |

Placebo |

Major cancer abdominal surgery |

Post- surgery |

24 hours post-surgery |

84 |

|

n.a. not available, n.s. normal saline

Results

If applicable, means and standard deviations were estimated from the medians and interquartile ranges using the method by Hozo (2005).

1. Postoperative pain

1.1 Postoperative pain at PACU arrival

Ng (2020) did not report postoperative pain at PACU arrival.

1.2 Postoperative pain at 6 hours post-surgery

Ng (2020) did not report postoperative pain at 6 hours.

1.3 Postoperative pain at 12 hours post-surgery

Ng (2020) did not report postoperative pain at 12 hours.

1.4 Postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery

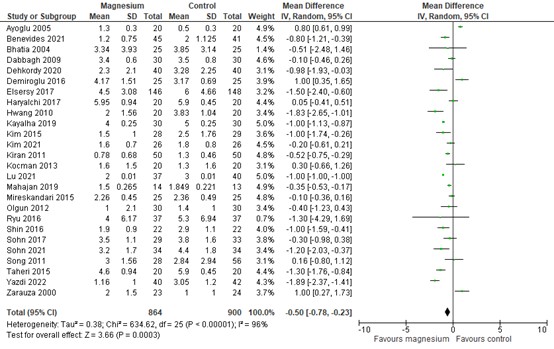

Postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery was reported by Ng (2020) with data from 18 RCTs and 8 additional RCTs. The results are presented in figure 1. A mean difference (MD) of -0.50 (95% confidence interval (CI): -0.78 to -0.23) was found in favour of magnesium. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Postoperative pain at 24h post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, 3 RCTs presented pain scores at 24 hours post-surgery in figures.

El Mourad (2019) presented VAS (scale 0-10) scores in figures. Pain scores were similar (both approximately 3.5 to 4; P= 0.193).

Moon (2020) reported NRS scores (scale 0-10) in figures. Median pain scores were approximately 3 (IQR 2-5) in the control group and 3 (IQR 1–4) in the magnesium group.

Tsaousi (2020) presented pain scores (scale 0-10) in figures. Median pain scores were approximately 1 (IQR 0-2) for magnesium and 2 (IQR 2-3) for control. Out of these three described studies, this is the only one describing a clinically relevant difference in favour of magnesium.

1.5 Postoperative pain at 48 hours post-surgery

Ng (2020) did not report postoperative pain at 48 hours.

2. Postoperative opioid consumption

2.1 In PACU

Ng (2020) did not report postoperative opioid consumption in PACU.

2.2 In 24h

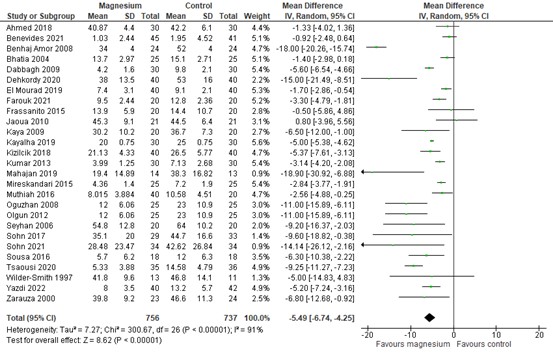

Postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was reported by Ng (2020) with data from 18 RCTs and 9 additional RCTs. The results are presented in figure 2. A MD of -5.49 (95% CI: -6.74 to -4.25) was found in favour of magnesium. This difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Postoperative opioid consumption in 24h post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, one RCT provided data on postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours post-surgery.

Moon (2020) reported cumulative postoperative fentanyl consumption (i.v.) at 24 hours post-surgery in figures. Fentanyl consumption was approximately 24 mg MME (i.v.) versus 32.5 mg MME (i.v.) in the magnesium and control group, respectively.

2.3 Total postoperative period

Ng (2020) did not report postoperative opioid consumption in the total postoperative period.

3. Adverse events

Bradycardia

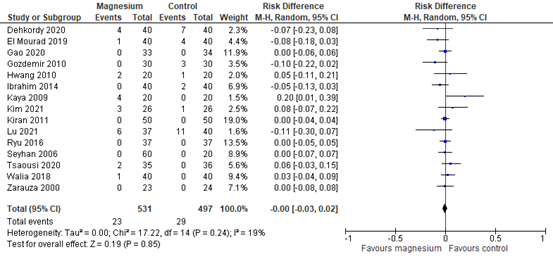

The incidence of bradycardia was reported by Ng (2020) with data from 9 RCTs and 6 additional RCTs. The results are presented in figure 3. A risk difference (RD) of -0.00 (95% -0.03 to 0.02) was found.

Figure 3. Adverse events - bradycardia

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, one RCT reported bradycardia without raw data.

Benevides (2021) reported a higher incidence of bradycardia in the magnesium group (11.1% vs 0%; P = 0.05), with a similar mean HR in both groups (p=0.054).

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measures postoperative pain, postoperative opioid consumption and adverse events started as high, because the studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at PACU arrival, at 6 hours, at 12 hours and at 48 hours post-surgery could not be assessed, as the included systematic review did not report these outcomes.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias; -1). The level of evidence for postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours is moderate (GRADE).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in PACU and in the total postoperative period could not be assessed, as the included systematic review did not report these outcomes.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias; -1). The level of evidence for postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours is moderate (GRADE).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure bradycardia was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias; -1) and imprecision (very low number of events; -1). The level of evidence for bradycardia is low (GRADE).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of adding magnesium perioperatively to standard care in surgical patients on postoperative pain, adverse outcomes and rescue analgesic consumption?

P (patients) patients undergoing a surgical procedure

I (intervention) perioperative i.v. magnesium + standard care

C (comparison) (placebo +) standard care

O (outcomes) postoperative pain

postoperative opioid consumption

adverse events (bradycardia)

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered postoperative pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and postoperative opioid consumption and adverse events as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Postoperative pain at rest: Validated pain scale (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) or Verbal Rating Scale (VRS)) at post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) arrival, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours post-surgery. Postoperative opioid consumption was assessed in PACU, 24 hours post-surgery and total postoperative period.

A priori, the working group did not define adverse events but used the definitions used in the studies.

Chronic postoperative pain is acknowledged by the working group as a relevant patient outcomes measure, however scarcely studied. In this literature analysis, chronic postoperative pain is not described in the PICO and results only mentioned in the knowledge gaps.

The working group defined one point as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference on a 10-point pain score and 10 mm on a 100 mm pain scale. Regarding postoperative opioid consumption, a difference of 10 mg was considered clinically relevant. For dichotomous variables, a difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant (RD 0.10).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms to identify systematic reviews published until 13-07-2022. This systematic literature search resulted in 317 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review (SR)

- Published between inception up to 13-07-2022

- Patients ≥ 18 years

- Conform PICO

After identifying the most relevant SR, the databases were searched to identify relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from January 2019 (search date: Ng, 2020) up to 13-07-2022. This systematic literature search resulted in 398 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- RCT

- Published between January 2019 and 13-07-2022

- Patients ≥ 18 years

- Conform PICO

The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods.

A total of 46 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 32 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 14 studies were included.

Results

Fourteen publications (1 SR reporting on 35 studies and 13 individual RCTs) were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Benevides ML, Fialho DC, Linck D, Oliveira AL, Ramalho DHV, Benevides MM. Intravenous magnesium sulfate for postoperative analgesia after abdominal hysterectomy under spinal anesthesia: a randomized, double-blind trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021 Sep-Oct;71(5):498-504. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.01.008. Epub 2021 Mar 21. PMID: 33762190; PMCID: PMC9373682.

- Dehkordy ME, Tavanaei R, Younesi E, Khorasanizade S, Farsani HA, Oraee-Yazdani S. Effects of perioperative magnesium sulfate infusion on intraoperative blood loss and postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing posterior lumbar spinal fusion surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020 Sep;196:105983. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105983. Epub 2020 Jun 2. PMID: 32521394.

- El Mourad MB, Arafa SK. Effect of intravenous versus intraperitoneal magnesium sulfate on hemodynamic parameters and postoperative analgesia during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy-A prospective randomized study. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2019 Apr-Jun;35(2):242-247. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_208_18. PMID: 31303716; PMCID: PMC6598561.

- Farouk I, Hassan MM, Fetouh AM, Elgayed AEA, Eldin MH, Abdelhamid BM. Analgesic and hemodynamic effects of intravenous infusion of magnesium sulphate versus dexmedetomidine in patients undergoing bilateral inguinal hernial surgeries under spinal anesthesia: a randomized controlled study. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021 Sep-Oct;71(5):489-497. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.004. Epub 2021 Feb 3. PMID: 34537120; PMCID: PMC9373243.

- Gao PF, Lin JY, Wang S, Zhang YF, Wang GQ, Xu Q, Guo X. Antinociceptive effects of magnesium sulfate for monitored anesthesia care during hysteroscopy: a randomized controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020 Sep 21;20(1):240. doi: 10.1186/s12871-020-01158-9. PMID: 32957926; PMCID: PMC7504853.

- Kayalha H, Yaghoubi S, Yazdi Z, Izadpanahi P. Effect of Intervenous Magnesium Sulfate on Decreasing Opioid Requirement after Surgery of the Lower Limb Fracture by Spinal Anesthesia. Int J Prev Med. 2019 May 6;10:57. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_320_17. PMID: 31143431; PMCID: PMC6528420.

- Kim HY, Lee SY, Lee HS, Jun BK, Choi JB, Kim JE. Beneficial Effects of Intravenous Magnesium Administration During Robotic Radical Prostatectomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Adv Ther. 2021 Mar;38(3):1701-1712. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01643-8. Epub 2021 Feb 21. PMID: 33611742.

- Lu J, Wang JF, Guo CL, Yin Q, Cheng W, Qian B. Intravenously injected lidocaine or magnesium improves the quality of early recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021 Mar 1;38(Suppl 1):S1-S8. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001348. PMID: 33074940.

- Mahajan C, Mishra RK, Jena BR, Kapoor I, Prabhakar H, Rath GP, Chaturvedi A. Effect of magnesium and lignocaine on post-craniotomy pain: A comparative, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019 Oct-Dec;13(4):299-305. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_837_18. PMID: 31572073; PMCID: PMC6753769.

- Murphy JD, Paskaradevan J, Eisler LL, Ouanes JP, Tomas VA, Freck EA, Wu CL. Analgesic efficacy of continuous intravenous magnesium infusion as an adjuvant to morphine for postoperative analgesia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2013 Feb;22(1):11-20. PMID: 23833845.

- Moon S, Lim S, Yun J, Lee W, Kim M, Cho K, Ki S. Additional effect of magnesium sulfate and vitamin C in laparoscopic gynecologic surgery for postoperative pain management: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2020 Jan 31;15(1):88-95. doi: 10.17085/apm.2020.15.1.88. PMID: 33329796; PMCID: PMC7713852.

- Ng KT, Yap JLL, Izham IN, Teoh WY, Kwok PE, Koh WJ. The effect of intravenous magnesium on postoperative morphine consumption in noncardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020 Mar;37(3):212-223. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001164. PMID: 31977626.

- Sohn HM, Kim BY, Bae YK, Seo WS, Jeon YT. Magnesium Sulfate Enables Patient Immobilization during Moderate Block and Ameliorates the Pain and Analgesic Requirements in Spine Surgery, Which Can Not Be Achieved with Opioid-Only Protocol: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. J Clin Med. 2021 Sep 22;10(19):4289. doi: 10.3390/jcm10194289. PMID: 34640307; PMCID: PMC8509453.

- Tsaousi G, Nikopoulou A, Pezikoglou I, Birba V, Grosomanidis V. Implementation of magnesium sulphate as an adjunct to multimodal analgesic approach for perioperative pain control in lumbar laminectomy surgery: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020 Oct;197:106091. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106091. Epub 2020 Jul 18. PMID: 32721845.

- Yazdi AP, Esmaeeli M, Gilani MT. Effect of intravenous magnesium on postoperative pain control for major abdominal surgery: a randomized double-blinded study. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2022 Jul;17(3):280-285. doi: 10.17085/apm.22156. Epub 2022 Jul 28. PMID: 35918860; PMCID: PMC9346203.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Ng, 2020 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

MD and OR values reported; no analysis corrected for confounding factors |

Yes; 6x low risk 11x high risk Rest: unclear |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes (for review, not for individual studies) |

Risk of bias of RCTs included in SR Ng, 2020 (from: Ng, 2020, according to the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool)

|

Study |

Sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding of participants and personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective outcome reporting |

Other sources of bias |

Overall |

|

Wilder-Smith 1997 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

Koinig 1998 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

|

Zarauza 2000 |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

Schulz-stubner 2001 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Levaux 2003 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Mavrommati 2004 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

High |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

|

Bhatia 2004 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Ayoglu 2005 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Seyhan 2006 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Tauzin-Fin 2006 |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Cizmeci 2007 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Tramer 2007 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Mentes 2008 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Benhaj amor 2008 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Ryu 2008 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Oguzhan 2008 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Unclear |

High |

|

Kaya 2009 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Dabbagh 2009 |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Hwang 2010 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Jaoua 2010 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Saadawy 2010 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Gozdemir 2010 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Ko 2011 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Song 2011 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

Kiran 2011 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Olgun 2012 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Khafagy 2012 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Kocman 2013 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Kumar 2013 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

DeOliveira 2014 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Ibrahim 2014 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Kahraman 2014 |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

Mireskandari 2015 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Frassanito 2015 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Taheri 2015 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Kim 2015 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

High |

High |

|

Asadollah 2015 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

low |

High |

High |

High |

|

Shah 2016 |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Demiroglu 2016 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Ryu 2016 |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

High |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Vickovic 2016 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Muthiah 2016 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Shin 2016 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Sousa 2016 |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Gucyetmez 2016 |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Shal 2017 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Sohn 2017 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

Low |

High |

High |

|

Elsersy 2017 |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

Unclear |

High |

Low |

Low |

Unclear |

|

Haryalchi 2017 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Walia 2018 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

High |

High |

Unclear |

High |

|

Kizilcik 2018 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

Ahmed 2018 |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Risk of bias of additional RCTs included

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Benevides, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Computer-generated randomization lists. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sealed, black envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients and outcome assessor blinded. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Dehkordy, 2020 |

Probably no;

Reason: no details on randomization method, except that block randomization was used |

Probably no;

Reason: not described |

Definitely yes;

Reason: everybody involved in the study was blinded |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

El Mourad, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Computer-generated randomization sequence |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sealed, opaque envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Farouk, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Computer-generated randomization sequence |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Concealment with serially numbered sealed opaque envelopes |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Gao, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computer-generated randomization Web-based, random number generator

|

Probably no;

Reason: not described |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Kayalha, 2019 |

Probably no;

Reason: ‘randomization by colorful cards’, no details provided |

Probably no;

Reason: not described |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patients and anesthesiologist were uninformed of the group assignment. No further details provided. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Kim, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computer-generated randomization technique |

Probably no;

Reason: not described |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No loss to follow-up reported |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Lu, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: randomization by a random number table generated by SPSS |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sealed, opaque envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Probably no;

Reason: Somewhat frequent loss to follow-up (17.8% in intervention group) |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns |

|

Mahajan, 2019 |

Definitlely yes;

Reason: computer‑generated table of random numbers |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Sealed, opaque envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Probably yes;

Reason: only loss to follow-up in the control group (17.8%) |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Moon, 2020 |

Probably yes;

Reason: drawing envelopes |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Sohn, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Computer-generated block randomization with blocks of size 4 |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provider, data collectors were blinded. Analysts are not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Tsaousi, 2020 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computer-generated randomization technique |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provide were blinded. Data collectors and analysts were not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

|

Yazdi, 2022 |

Probably yes;

Reason: online random number table |

Probably yes;

Reason: sealed envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: Patient, health care provide were blinded. Data collectors and analysts were not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW |

Evidence table for intervention studies – SRs – descriptives

|

Study reference |

RCT reference |

Study designs |

Setting and country |

Funding and conflicts of interest |

N at baseline; age (sd) |

Type of surgery; timing of intervention |

Intervention regime |

Intervention |

Control |

Postoperative analgesia |

Loss-to-follow-up / etamizole data |

|

Ng, 2020 |

A: Wilder-Smith, 1997 B: Koinig, 1998 C: Zarauza, 2000 D: Schulz-Stübner, 2001 E: Levaux, 2003 F: Mavrommati, 2004 G: Bhatia, 2004 H: Ayoglu, 2005 I: Seyhan, 2006 J: Tauzin-Fin, 2006 K: Cizmeci, 2007 L: Tramer, 2007 M: Mentes, 2008 N: Benhaj Amor, 2008 O: Ryu, 2008 P: Oguzhan, 2008 Q: Kaya, 2009 R: Dabbagh, 2009 S: Hwang, 2010 T: Jaouda, 2010 U: Saadawy, 2010 V: Gozdemir, 2010 W: Koinig, 2011 X: Song, 2011 Y: Kiran, 2011 Z: Olgun, 2012 AA: Khafagy, 2012 BB: Kocman, 2013 CC: Kumar, 2013 DD: de Oliveira, 2013 EE: Ibrahim, 2014 FF: Kahraman, 2014 GG: Mireskandari, 2015 HH: Frassanito, 2015 II: Taheri, 2015 JJ: Kim, 2015 KK: Asadollah, 2015 LL: Shah, 2016 MM: Demiroglu, 2016 NN: Ryu, 2016 OO: Vickovic, 2016 PP: Muthiah, 2016 QQ: Shin, 2016 RR: Sousa, 2016 SS: Gucyetmez, 2016 TT: Shal, 2017 UU: Sohn, 2017 VV: Elsersy, 2017 WW: Haryalchi, 2017 XX: Walia, 2018 YY: Kizilcik, 2018 ZZ: Ahmed, 2018 |

A: RCT B: RCT C: RCT D: RCT E: RCT F: RCT G: RCT H: RCT I: RCT J: RCT K: RCT L: RCT M: RCT N: RCT O: RCT P: RCT Q: RCT R: RCT S: RCT T: RCT U: RCT V: RCT W: RCT X: RCT Y: RCT Z: RCT AA: RCT BB: RCT CC: RCT DD: RCT EE: RCT FF: RCT GG: RCT HH: RCT II: RCT JJ: RCT KK: RCT LL: RCT MM: RCT NN: RCT OO: RCT PP: RCT QQ: RCT RR: RCT SS: RCT TT: RCT UU: RCT VV: RCT WW: RCT XX: RCT YY: RCT ZZ: RCT |

A: n.s., Switserland B: n.s., Austria C: n.s., Spain D: n.s., Germany E: n.s., Belgium F: n.s., Greece G: n.s., India H: n.s., Europe I: n.s., Turkey J: n.s., France K: n.s., Turkey L: n.s., Switserland M: n.s., Turkey N: n.s., France O: n.s., South Korea P: n.s., Turkey Q: n.s., Turkey R: n.s., Iran S: n.s., South Korea T: n.s., Tunesia U: n.s., Egypt V: n.s., Turkey W: n.s., South Korea X: n.s., South Korea Y: n.s., India Z: n.s., Turkey AA: n.s., Egypt BB: n.s., Croatia CC: n.s., India DD: n.s., USA EE: n.s., Egypt FF: n.s., Turkey GG: n.s., Iran HH: n.s., Italy II: n.s., Iran JJ: n.s., South Korea KK: n.s., Iran LL: n.s., India MM: n.s., Turkey NN: n.s., South Korea OO: n.s., Serbia PP: n.s., India QQ: n.s., South Korea RR: n.s., Brazil SS: n.s., Turkey TT: n.s., Egypt UU: n.s., South Korea VV: n.s., Egypt WW: n.s., Iran XX: n.s., India YY: n.s., Turkey ZZ: n.s., Egypt |

A: n.s. B: n.s. C: n.s. D: n.s. E: n.s. F: n.s. G: n.s. H: n.s. I: n.s. J: n.s. K: n.s. L: n.s. M: n.s. N: n.s. O: n.s. P: n.s. Q: n.s. R: n.s. S: n.s. T: n.s. U: n.s. V: n.s. W: n.s. X: n.s. Y: n.s. Z: n.s. AA: n.s. BB: n.s. CC: n.s. DD: n.s. EE: n.s. FF: n.s. GG: n.s. HH: n.s. II: n.s. JJ: n.s. KK: n.s. LL: n.s. MM: n.s. NN: n.s. OO: n.s. PP: n.s. QQ: n.s. RR: n.s. SS: n.s. TT: n.s. UU: n.s. VV: n.s. WW: n.s. XX: n.s. YY: n.s. ZZ: n.s. |

A: 24; n.s. (n.s.) B: 46; n.s. (n.s.) C: 92; n.s. (n.s.) D: 50; n.s. (n.s.) E: 24; n.s. (n.s.) F: 42; n.s. (n.s.) G: 50; n.s. (n.s.) H: 40; n.s. (n.s.) I: 60; n.s. (n.s.) J: 30; n.s. (n.s.) K: 60; n.s. (n.s.) L: 200; n.s. (n.s.) M: 83; n.s. (n.s.) N: 48; n.s. (n.s.) O: 50; n.s. (n.s.) P: 50; n.s. (n.s.) Q: 40; n.s. (n.s.) R: 60; n.s. (n.s.) S: 40; n.s. (n.s.) T: 38; n.s. (n.s.) U: 80; n.s. (n.s.) V: 60; n.s. (n.s.) W: 58; n.s. (n.s.) X: 84; n.s. (n.s.) Y: 100; n.s. (n.s.) Z: 60; n.s. (n.s.) AA: 60; n.s. (n.s.) BB: 60; n.s. (n.s.) CC: 60; n.s. (n.s.) DD: 46; n.s. (n.s.) EE: 80; n.s. (n.s.) FF: 38; n.s. (n.s.) GG: 50; n.s. (n.s.) HH: 40; n.s. (n.s.) II: 40; n.s. (n.s.) JJ: 60; n.s. (n.s.) KK: 30; n.s. (n.s.) LL: 108; n.s. (n.s.) MM: 50; n.s. (n.s.) NN: 74; n.s. (n.s.) OO: 100; n.s. (n.s.) PP: 40; n.s. (n.s.) QQ: 44; n.s. (n.s.) RR: 36; n.s. (n.s.) SS: 70; n.s. (n.s.) TT: 70; n.s. (n.s.) UU: 62; n.s. (n.s.) VV: 294; n.s. (n.s.) WW: 40; n.s. (n.s.) XX: 80; n.s. (n.s.) YY: 80; n.s. (n.s.) ZZ: 60; n.s. (n.s.) |

A: Hysterectomy; Before anaesthesia induction B: Arthroscopic knee surgery; After anaesthesia induction C: Colorectal surgery; Before anaesthesia induction D: Pars plana vitrectomy; After anaesthesia induction E: Lumbar orthopaedics surgery; Before anaesthesia induction F: Abdominal hernioplasty; After anaesthesia induction G: Open cholecystectomy; Before anaesthesia induction H: Abdominal surgery; Before anaesthesia induction I: Total abdominal hysterectomy; Before anaesthesia induction J: Radical prostatectomy; After anaesthesia induction K: Septorhinoplasty; Before anaesthesia induction L: Ambulatory ilioinguinal hernia repair/ varicose vein operation; After anaesthesia induction M: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; After anaesthesia induction N: Open cholecystectomy, gastrojejunal surgery; During anaesthesia induction O: Abdominal hysterectomy; Before anaesthesia induction P: Lumbar orthopaedic surgery; After anaesthesia induction Q: Abdominal hysterectomy; Before anaesthesia induction R: Lower limb orthopaedic surgery; After anaesthesia induction S: Total hip arthroplasty; After anaesthesia induction T: Gastrointestinal surgery; Before anaesthesia induction U: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Before anaesthesia induction V: Transurethral prostatectomy; After anaesthesia induction W: Abdominal hysterectomy; After anaesthesia induction X: Thyroidectomy; After anaesthesia induction Y: Inguinal surgery; Before anaesthesia induction Z: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Before anaesthesia induction AA: Open cholecystectomy; After anaesthesia induction BB: Elective subumbilical surgery; Before anaesthesia induction CC: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Before anaesthesia induction DD: Segmental mastectomy; Before anaesthesia induction EE: Lower extraperitoneal and lower limb surgery; Before anaesthesia induction FF: Abdominal hysterectomy; After anaesthesia induction GG: Caesarean section; Before anaesthesia induction HH: Total knee amputation; After anaesthesia induction II: Abdominal hysterectomy; Before anaesthesia induction JJ: Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplasm; Before anaesthesia induction KK: Hysterectomy/ Myomectomy; Before anaesthesia induction LL: Lower abdominal and lower limb surgery; After anaesthesia induction MM: Lumbar disc surgery; After anaesthesia induction NN: Laparoscopic gastrectomy; After anaesthesia induction OO: Abdominal, orthopaedic, urology surgery; Before anaesthesia induction PP: Arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament repair; Before anaesthesia induction QQ: Bilateral total knee amputation; During anaesthesia induction RR: Laparoscopic gynaecological surgery; After anaesthesia induction SS: Liver transplant; After anaesthesia induction TT: Arthroscopic knee surgery; Before anaesthesia induction UU: Thoracoscopic surgery; After anaesthesia induction VV: Functional endoscopy surgery; Before anaesthesia induction WW: Total abdominal hysterectomy; During anaesthesia induction XX: Elective surgery; Before anaesthesia induction YY: Sleeve gastrectomy; Before anaesthesia induction ZZ: Thoracic surgery; Before anaesthesia induction |

A: Bolus + infusion B: Bolus + infusion C: Bolus + infusion D: Bolus E: Bolus F: Bolus + infusion G: Bolus + infusion H: Bolus + infusion I: Bolus + infusion J: Bolus K: Bolus + infusion L: Bolus M: Infusion N: Bolus + infusion O: Bolus + infusion P: Bolus + infusion Q: Bolus + infusion R: Infusion S: Bolus + infusion T: Bolus + infusion U: Bolus + infusion V: Infusion W: Bolus + infusion X: Bolus + infusion Y: Infusion Z: Bolus + infusion AA: Infusion BB: Infusion CC: Bolus + infusion DD: Bolus + infusion EE: Bolus + infusion FF: Infusion GG: Bolus HH: Bolus + infusion II: Infusion JJ: Infusion KK: Bolus + infusion LL: Bolus + infusion MM: Infusion NN: Bolus + infusion OO: Bolus + infusion PP: Infusion QQ: Bolus + infusion RR: Bolus + infusion SS: Infusion TT: Bolus + infusion UU: Bolus + infusion VV: Infusion WW: Infusion XX: Infusion YY: Bolus + infusion ZZ: Infusion |

A: 200 mg/h B: 8 mg/kg/h C: 10 mg/kg/h D: n.a. E: n.a. F: 6 mg/kg/h G: 15 mg/kg/h H: 8 mg/kg/h I: 10 mg/kg/h, 20 mg/kg/h J: n.a. K: 8 mg/kg/h L: n.a. M: 50 mg/kg/h N: 500 mg/h O: 15 mg/kg/h P: 10 mg/kg/h Q: 500 mg/h R: 8 mg/kg/h S: 15 mg/kg/h T: 10 mg/kg/h U: 25 mg/kg/h V: 80 mg/kg/h, 2 g/h W: 15 mg/kg/h X: 10 mg/kg/h Y: 50 mg/kg/h Z: 10 mg/kg/h AA: 8 mg/kg/h BB: 5 mg/kg/h CC: 10 mg/kg/h DD: 15 mg/kg/h EE: 2 mg/kg/h FF: 65 mg/kg/h GG: n.a. HH: 10 mg/kg/h II: 50 mg/kg/h JJ: 50 mg/kg/h KK: 8 mg/kg/h LL: 20 mg/kg/h MM: 50 mg/kg/h NN: 15 mg/kg/h OO: 10 mg/kg/h PP: 150 mg/h QQ: 15 mg/kg/h RR: 2 mg/kg/h SS: 50 mg/kg/h TT: 10 mg/kg/h UU: 15 mg/kg/h VV: 30 mg/kg/h WW: 15 mg/kg/h XX: 30 mg/kg/h YY: 20 mg/kg/h ZZ: 50 mg/kg/h |

A: n.s. B: n.s. C: n.s. D: n.s. E: n.s. F: n.s. G: n.s. H: n.s. I: n.s. J: n.s. K: n.s. L: n.s. M: n.s. N: n.s. O: n.s. P: n.s. Q: n.s. R: n.s. S: n.s. T: n.s. U: n.s. V: n.s. W: n.s. X: n.s. Y: n.s. Z: n.s. AA: n.s. BB: n.s. CC: n.s. DD: n.s. EE: n.s. FF: n.s. GG: n.s. HH: n.s. II: n.s. JJ: n.s. KK: n.s. LL: n.s. MM: n.s. NN: n.s. OO: n.s. PP: n.s. QQ: n.s. RR: n.s. SS: n.s. TT: n.s. UU: n.s. VV: n.s. WW: n.s. XX: n.s. YY: n.s. ZZ: n.s. |

A: PCA morphine B: IV fentanyl C: PCA morphine NSAIDs IV paracetamol IV metamizole D: IV metamizol IV nalbuphine E: IV metamizol IV nalbuphine F: IV fentanyl G: IV morphine H: IV alfentanil I: PCA morphine J: PCA tramadol PCA droperidol K: IV meperidine L: Oral/rectal NSAID IV/IM opioid M: PCA tramadol N: PCA morphine O: PCA mixture, ketorolac and morphine P: PCA morphine Q: PCA morphine R: IV morphine S: PCA mixture, ketorolac and morphine T: PCA morphine U: PCA morphine. The actual dose was not provided V: IV pethidine W: IV lidocaine PCA fentanyl X: Tab Ultracet IM tramadol Y: IV pethidine IM diclofenac Z: PCA morphine AA: IV meperidine BB: IV metamizol IV diclofenac IV tramadol CC: IV morphine DD: IV hydromorphone EE: IV meperidine FF: IV tramadol GG: PCA morphine HH: IV paracetamol IV ketorolac PCA morphine II: IV pethidine JJ: IV ketorolac IV tramadol KK: IV pethidine LL: IV tramadol MM: IM diclofenac PCA tramadol NN: PCA fentanyl OO: IV fentanyl PP: IV morphine QQ: PCA fentanyl IV ketoprofen RR: PCA morphine SS: IV tramadol TT: IV pethidine UU: IV morphine IV fentanyl IV NSAIDs" VV: IV pethidine WW: IV fentanyl XX: IV propofol YY: PCA morphine IV fentanyl" ZZ: PCA morphine |

A: n.s. B: n.s. C: n.s. D: n.s. E: n.s. F: n.s. G: n.s. H: n.s. I: n.s. J: n.s. K: n.s. L: n.s. M: n.s. N: n.s. O: n.s. P: n.s. Q: n.s. R: n.s. S: n.s. T: n.s. U: n.s. V: n.s. W: n.s. X: n.s. Y: n.s. Z: n.s. AA: n.s. BB: n.s. CC: n.s. DD: n.s. EE: n.s. FF: n.s. GG: n.s. HH: n.s. II: n.s. JJ: n.s. KK: n.s. LL: n.s. MM: n.s. NN: n.s. OO: n.s. PP: n.s. QQ: n.s. RR: n.s. SS: n.s. TT: n.s. UU: n.s. VV: n.s. WW: n.s. XX: n.s. YY: n.s. ZZ: n.s. |

|

|

Postoperative pain 24h

|

Postoperative morphine consumption – 24h |

Adverse events: bradycardia |

||||||||||||||||

|

Study reference |

Studies |

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

Control |

Intervention |

Control |

||||||||||||

|

|

|

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Mean |

SD |

N |

Events |

Total |

|

Events |

Total |

|

|

Ng, 2020 |

A: Wilder-Smith, 1997 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

41.8 |

9.6 |

13 |

46.8 |

14.1 |

11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B: Koinig, 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C: Zarauza, 2000 |

2.0 |

1.5 |

23 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

24 |

39.8 |

9.2 |

23 |

46.6 |

11.3 |

24 |

0 |

23 |

|

0 |

24 |

|

|

|

D: Schulz-Stübner, 2001 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E: Levaux, 2003 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F: Mavrommati, 2004 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

G: Bhatia, 2004 |

3.34 |

3.93 |

25 |

3.85 |

3.14 |

25 |

13.7 |

2.97 |

25 |

15.1 |

2.71 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

H: Ayoglu, 2005 |

1.3 |

0.3 |

20 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I: Seyhan, 2006 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

54.8 |

12.8 |

20 |

64.0 |

10.2 |

20 |

0 |

60 |

|

0 |

20 |

|

|

|

J: Tauzin-Fin, 2006 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

K: Cizmeci, 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L: Tramer, 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

M: Mentes, 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

N: Benhaj Amor, 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

34.0 |

4.0 |

24 |

52.0 |

4.0 |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O: Ryu, 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P: Oguzhan, 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

12.0 |

6.06 |

25 |

23.0 |

10.9 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Q: Kaya, 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30.2 |

10.2 |

20 |

36.7 |

7.3 |

20 |

4 |

20 |

|

0 |

20 |

|

|

|

R: Dabbagh, 2009 |

3.4 |

0.6 |

30 |

3.5 |

0.8 |

30 |

4.2 |

1.6 |

30 |

9.8 |

2.1 |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S: Hwang, 2010 |

2.0 |

1.56 |

20 |

3.83 |

1.04 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

20 |

|

1 |

20 |

|

|

|

T: Jaouda, 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

45.3 |

9.1 |

21 |

44.5 |

6.4 |

21 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

U: Saadawy, 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V: Gozdemir, 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

30 |

|

3 |

30 |

|

|

|

W: Koinig, 2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

X: Song, 2011 |

3.0 |

1.56 |

28 |

2.84 |

2.94 |

56 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y: Kiran, 2011 |

0.78 |

0.68 |

50 |

1.3 |

0.46 |

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

50 |

|

0 |

50 |

|

|

|

Z: Olgun, 2012 |

1.0 |

2.1 |

30 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

30 |

12.0 |

6.06 |

25 |

23.0 |

10.9 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AA: Khafagy, 2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BB: Kocman, 2013 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

20 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CC: Kumar, 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.99 |

1.25 |

30 |

7.13 |

2.68 |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DD: de Oliveira, 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EE: Ibrahim, 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

40 |

|

2 |

40 |

|

|

|

FF: Kahraman, 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

GG: Mireskandari, 2015 |

2.26 |

0.45 |

25 |

2.36 |

0.49 |

25 |

4.36 |

1.4 |

25 |

7.2 |

1.9 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HH: Frassanito, 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

13.9 |

5.9 |

20 |

14.4 |

10.7 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

II: Taheri, 2015 |

4.6 |

0.94 |

20 |

5.9 |

0.45 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JJ: Kim, 2015 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

28 |

2.5 |

1.76 |

29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

KK: Asadollah, 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LL: Shah, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MM: Demiroglu, 2016 |

4.17 |

1.51 |

25 |

3.17 |

0.69 |

25 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

NN: Ryu, 2016 |

4.0 |

6.17 |

37 |

5.3 |

6.94 |

37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

37 |

|

0 |

37 |

|

|

|

OO: Vickovic, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PP: Muthiah, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

8.015 |

3.884 |

40 |

10.58 |

4.51 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

QQ: Shin, 2016 |

1.9 |

0.9 |

22 |

2.9 |

1.1 |

22 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RR: Sousa, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5.7 |

6.2 |

18 |

12.0 |

6.3 |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SS: Gucyetmez, 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TT: Shal, 2017 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

UU: Sohn, 2017 |

3.5 |

1.1 |

29 |

3.8 |

1.6 |

33 |

35.1 |

20.0 |

29 |

44.7 |

16.6 |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VV: Elsersy, 2017 |

4.5 |

3.08 |

146 |

6.0 |

4.66 |

148 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WW: Haryalchi, 2017 |

5.95 |

0.94 |

20 |

5.9 |

0.45 |

20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

XX: Walia, 2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

40 |

|

0 |

40 |

|

|

|

YY: Kizilcik, 2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

21.13 |

4.33 |

40 |

26.5 |

5.77 |

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ZZ: Ahmed, 2018 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

40.87 |

4.4 |

30 |

42.2 |

6.1 |

30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evidence table for intervention studies (additional randomized controlled trials)

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abdelgalil A, Shoukry AA, Kamel MA, Heikal AMY, Ahmed NA. Analgesic Potentials of Preoperative Oral Pregabalin, Intravenous Magnesium Sulfate, and their Combination in Acute Postthoracotomy Pain. Clin J Pain. 2019 Mar;35(3):247-251. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000673. PMID: 30730476. |

Wrong population |

|

Adhikary SD, Thiruvenkatarajan V, McFadden A, Liu WM, Mets B, Rogers A. Analgesic efficacy of ketamine and magnesium after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2021 Feb;68:110097. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.110097. Epub 2020 Oct 23. PMID: 33120301. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Bansal, K., Santpur, M. U., Garg, U., Goel, K., Vijay, D., & Venugopal, T. Effect of intravenous magnesium sulphate on hemodynamic response to pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective, double blind study. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care. 2021; 290-294. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Choi GJ, Kim YI, Koo YH, Oh HC, Kang H. Perioperative Magnesium for Postoperative Analgesia: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Pers Med. 2021 Dec 2;11(12):1273. doi: 10.3390/jpm11121273. PMID: 34945745; PMCID: PMC8708823. |

Wrong publication type |

|

Deshpande JP, Patil KN. Evaluation of magnesium as an adjuvant to ropivacaine-induced axillary brachial plexus block: A prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Indian J Anaesth. 2020 Apr;64(4):310-315. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_833_19. Epub 2020 Mar 28. PMID: 32489206; PMCID: PMC7259414. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Fei S, Xia H, Chen X, Pang D, Xu X. Magnesium sulfate reduces the rocuronium dose needed for satisfactory double lumen tube placement conditions in patients with myasthenia gravis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Aug 31;19(1):170. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0841-4. PMID: 31472669; PMCID: PMC6717642. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Gol M, Aghamohammadi D. Effect of intravenous infusion of magnesium sulfate on opioid use and hemodynamic status after hysterectomy: double-blind clinical trial. The Iranian Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2019;22(7):32-8. |

Wrong language |

|

Hassan WF, Tawfik MH, Nabil TM, Abd Elkareem RM. Could intraoperative magnesium sulphate protect against postoperative cognitive dysfunction? Minerva Anestesiol. 2020 Aug;86(8):808-815. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.20.14012-4. Epub 2020 May 22. PMID: 32449335. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Hassan ME, Mahran E. Effect of magnesium sulfate with ketamine infusions on intraoperative and postoperative analgesia in cancer breast surgeries: a randomized double-blind trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021 Jul 29:S0104-0014(21)00296-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.07.015. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34332956. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Jitsinthunun T, Raksakietisak M, Pantubtim C, Mahatnirunkul P. Effects of Magnesium Sulfate on Intraoperative Blood Loss and Anesthetic Requirement in Meningioma Patients Undergoing Craniotomy with Tumor Removal: A Prospective Randomized Study. Journal of Neuroanaesthesiology and Critical Care. 2022 Jul 20. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Kamel AA, Ibrahem Amin OA. The Effect of preoperative nebulized: Magnesium sulfate versus lidocaine on the prevention of post-intubation sore throat. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2020 Jan 1;36(1):1-6. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Kosucu M, Tugcugil E, Arslan E, Omur S, Livaoglu M. Effects of perioperative magnesium sulfate with controlled hypotension on intraoperative bleeding and postoperative ecchymosis and edema in open rhinoplasty. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020 Nov-Dec;41(6):102722. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102722. Epub 2020 Sep 14. PMID: 32950829. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Mashak B, Pouryaghobi SM, Rezaee M, Rad SS, Ataei M, Borzabadi A. Evaluation of the Effects of Magnesium Sulfate on Prevention of Post-dural-Puncture Headache in Elective Cesarean in Kamali Hospital. ELECTRON J GEN MED. 2020;17(3), em199. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Masoudifar, M., Mostashfi, M., Hirmanpour, A. Comparative Study of the Effect of Prophylactic Administration of Two Doses of Magnesium Sulfate and Placebo on Cardiovascular Changes during General Anesthesia in Gynecologic Laparoscopic Surgeries. Journal of Isfahan Medical School, 2019; 37(528): 572-579. doi: 10.22122/jims.v37i528.11214 |

Wrong language |

|

Mendonça FT, Pellizzaro D, Grossi BJ, Calvano LA, de Carvalho LSF, Sposito AC. Synergistic effect of the association between lidocaine and magnesium sulfate on peri-operative pain after mastectomy: A randomised, double-blind trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020 Mar;37(3):224-234. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001153. PMID: 31977625. |

Wrong comparator |

|

Modir H, Modir A, Rezaei O, Mohammadbeigi A. Comparing remifentanil, magnesium sulfate, and dexmedetomidine for intraoperative hypotension and bleeding and postoperative recovery in endoscopic sinus surgery and tympanomastoidectomy. Med Gas Res. 2018 Jul 3;8(2):42-47. doi: 10.4103/2045-9912.235124. PMID: 30112164; PMCID: PMC6070837. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Sabaa M A, Elbadry A A, Hegazy S, El Malla D A. Intravenous Versus Wetting Solution Magnesium Sulphate to Counteract Epinephrine Cardiac Adverse Events in Abdominal Liposuction: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesth Pain Med. 2022;12(5):e129807. https://doi.org/10.5812/aapm-129807. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Saeed R, Sarwar M, Javed A, Qamar I, Bangash T, Kakepotto IA. Atracurium With and Without Administrating Magnesium Sulphate in Patients Undergoing Abdominal Surgeries. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Sane S, Mahdkhah A, Golabi P, Hesami SA, Kazemi Haki B. Comparison the effect of bupivacaine plus magnesium sulfate with ropivacaine plus magnesium sulfate infiltration on postoperative pain in patients undergoing lumbar laminectomy with general anesthesia. Br J Neurosurg. 2020 Dec 17:1-4. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2020.1861430. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33332200. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Sharma A, Jaswal S, Jaswal V, Pathania J. Effect of Magnesium Sulphate as an Adjuvant to Bupivacaine in Interscalene Brachial Plexus Block for Postoperative Analgesia. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research. 2019 Oct 1;13(10). |

Wrong intervention |

|

Shim JW, Cha S, Moon HW, Moon YE. Effects of Intraoperative Magnesium and Ketorolac on Catheter-Related Bladder Discomfort after Transurethral Bladder Tumor Resection: A Prospective Randomized Study. J Clin Med. 2022 Oct 27;11(21):6359. doi: 10.3390/jcm11216359. PMID: 36362587; PMCID: PMC9659173. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Shukla U, Singh D, Yadav JBS, Azad MS. Dexmedetomidine and Magnesium Sulfate as Adjuvant to 0.5% Ropivacaine in Supraclavicular Brachial Plexus Block: A Comparative Evaluation. Anesth Essays Res. 2020 Oct-Dec;14(4):572-577. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_28_21. Epub 2021 May 27. PMID: 34349322; PMCID: PMC8294421. |

Wrong intervention |

|

Silva Filho SE, Sandes CS, Vieira JE, Cavalcanti IL. Analgesic effect of magnesium sulfate during total intravenous anesthesia: randomized clinical study. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021 Sep-Oct;71(5):550-557. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.008. Epub 2021 Feb 3. PMID: 34537125; PMCID: PMC9373246. |

Wrong comparator |

|

Silva Filho SE, Dainez S, Gonzalez MAMC, Angelis F, Vieira JE, Sandes CS. Intraoperative Analgesia with Magnesium Sulfate versus Remifentanil Guided by Plethysmographic Stress Index in Post-Bariatric Dermolipectomy: A Randomized Study. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2022 Oct 26;2022:2642488. doi: 10.1155/2022/2642488. PMID: 36339775; PMCID: PMC9629917. |

Wrong comparator |

|

Sohair A. Megalla, Khaled A. Abdou & Ahmed I. Mohamed (2019) Bispectral index guided attenuation of hemodynamic and arousal response to endotracheal intubation using magnesium sulfate and fentanyl. Randomized, controlled trial, Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia, 35:1, 43-48, DOI: 10.1080/11101849.2019.1595346 |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Soliman R, Abukhudair W. The perioperative effect of magnesium sulfate in patients with concentric left ventricular hypertrophy undergoing cardiac surgery: A double-blinded randomized study. Ann Card Anaesth. 2019 Jul-Sep;22(3):246-253. doi: 10.4103/aca.ACA_34_18. PMID: 31274484; PMCID: PMC6639894. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Queiroz Rangel Micuci AJ, Verçosa N, Filho PAG, de Boer HD, Barbosa DD, Cavalcanti IL. Effect of pretreatment with magnesium sulphate on the duration of intense and deep neuromuscular blockade with rocuronium: A randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019 Jul;36(7):502-508. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001003. PMID: 30985540. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Tan W, Qian DC, Zheng MM, Lu X, Han Y, Qi DY. Effects of different doses of magnesium sulfate on pneumoperitoneum-related hemodynamic changes in patients undergoing gastrointestinal laparoscopy: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Dec 20;19(1):237. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0886-4. PMID: 31862004; PMCID: PMC6925413. |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Varas V, Bertinelli P, Carrasco P, Souper N, Álvarez P, Danilla S, Egaña JI, Penna A, Sepúlveda S, Arancibia V, Álvarez MG, Vergara R. Intraoperative Ketamine and Magnesium Therapy to Control Postoperative Pain After Abdominoplasty and/or Liposuction: A Clinical Randomized Trial. J Pain Res. 2020 Nov 16;13:2937-2946. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S276710. PMID: 33235492; PMCID: PMC7678693. |

Wrong comparison |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 01-09-2023

Laatst geautoriseerd : 01-09-2023

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-09-2028

Algemene gegevens