Lidocaïne

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de meerwaarde van de perioperatieve toevoeging van lidocaïne intraveneus bij patiënten die een chirurgische ingreep ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Overweeg het perioperatief toedienen van lidocaïne bij patiënten met een risico op chronische postoperatieve pijn.

Overweeg het perioperatief toedienen van lidocaïne als alternatief voor epidurale pijnbestrijding.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar de effectiviteit van perioperatief lidocaïne vergeleken met standard care en vergeleken met epidurale analgesie. Postoperatieve pijn was de cruciale uitkomstmaat en het postoperatieve gebruik van opioïden was een belangrijke uitkomstmaat voor klinische besluitvorming.

- Lidocaïne vs. standaardzorg (zonder epiduraal)

Voor de eerste vergelijking, lidocaïne versus standard care, is voor postoperatieve pijn op de verkoever een lage bewijskracht gevonden. Dit kwam vanwege risico op bias en imprecisie.

Voor postoperatieve pijn op 6, 12, 24 en 48 uur werd een redelijke bewijskracht gevonden. Er is alleen afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias.

Voor chronische pijn was de bewijskracht redelijk, vanwege een klein aantal studies met weinig deelnemers.

Voor postoperatieve pijn werden op alle tijdstippen lagere scores gezien in de lidocaïne groepen, maar bij geen van allen was dit verschil klinisch relevant.

Alleen voor chronische pijn werd een klinisch relevant verschil gevonden in het voordeel van lidocaïne.

Voor postoperatief gebruik van opioïden was er een redelijke bewijskracht voor de periode in de verkoever, 24 uur na de ingreep en in de totale postoperatieve periode. Er werd afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias. Ook hier waren de verschillen tussen de interventies niet klinisch relevant.

Cardiotoxiciteit (hartritmestoornissen en hypotensie) hadden beiden een redelijke bewijskracht. Er werd alleen afgewaardeerd voor een klein aantal events. Voor lidocaïne-geïnduceerde neurotoxiciteit werden weinig verschijnselen gerapporteerd. Door het lage aantal events en risico op bias kwam dit uit op een lage bewijskracht. Er werden geen klinisch relevante resultaten gevonden. Dus lidocaïne is veilig in de toegediende doseringen en met eventuele monitoring.

Voor beide vergelijkingen lijkt het daarom op basis van de literatuur dat niet één van beide interventies overtuigend de voorkeur heeft boven de andere. Uit eerdere reviews kwam dat lidocaïne lagere pijnscores, vermindering van opioïden, postoperatieve ileus en opnameduur in het ziekenhuis bij abdominale chirurgie zou kunnen geven (Dunn, 2017). In deze analyse zijn alle operaties samengevoegd, maar bij subgroep-analyses kwam geen verschil tussen specifieke chirurgische procedures uit of door dosering (<2 mg/kg/h en >2 mg/kg/h. Incidentie van postoperatieve ileus en duur van ziekenhuisopname zijn niet meegenomen in onze analyse.

Ondanks dat uit de subgroep-analyse geen verschil werd gevonden tussen de dosering van lidocaïne, blijft dit een onderwerp van debat in de literatuur: welke dosering als bolus en continue infusie, wanneer te starten en te eindigen. Uit de geanalyseerde literatuur komt naar voren dat bij de meeste studies een bolus van 1.5 mg/kg (op basis van ideal body weight) bij inleiding van de anesthesie, gevolgd door een continue infusie van 1.5-2 mg/kg/uur tot het einde van de operatie werd gegeven.

- Lidocaïne vs. epidurale pijnbestrijding

Voor de tweede vergelijking, lidocaïne versus epidurale analgesie, was er weinig literatuur beschikbaar. In de studies die beschikbaar waren, bestond de populatie met name uit patiënten die buikoperaties of oncologische chirurgie ondergingen. Het is dus de vraag of de interventie voor alle typen chirurgie even effectief is.

Postoperatieve pijn in de verkoever en 6 uur na de operatie kwam uit op een zeer lage bewijskracht. Er is afgewaardeerd voor risico op bias en het kleine aantal geïncludeerde studies. Voor latere tijdstippen, 12, 24 en 48 uur postoperatief, was de bewijskracht laag. Om dezelfde redenen werd weer afgewaardeerd.

Voor de tijdstippen 24 en 48 uur postoperatief was de pijnscore lager bij de patiënten die lidocaïne kregen toegediend, echter de verschillen waren niet klinisch relevant (MD 0.99 op 24 uur en MD 0.96 op 48 uur).

Chronische pijn werd in geen van de studies gerapporteerd, waardoor er op basis van de beschikbare literatuur geen conclusie getrokken kon worden.

Voor postoperatief opiaatgebruik werden geen studies gevonden die dit rapporteerden in de verkoever. Op 24 uur na de ingreep was de bewijskracht laag vanwege risico op bias en een klein aantal studies met weinig patiënten. Opiaatgebruik in de totale postoperatieve periode kwam uit op een lage bewijskracht door een klein aantal geïncludeerde patiënten.

Bij epidurale pijnbestrijding werden minder opioïden toegediend (> 10 mg verschil op 24 uur), maar konden er door de lage bewijskracht geen eenduidige conclusies worden getrokken. Daarnaast moet opgemerkt worden dat opioïden ook epiduraal worden toegediend, en dat deze ook meegenomen zijn in het berekende morfinegebruik. Wanneer uitsluitend gekeken werd naar het gebruik van doorbraakmedicatie, was dit niet verschillend voor beide groepen. In de meest eerlijke vergelijking waarbij de samenstelling van de PCA-pomp hetzelfde was in de lidocaïne en epidurale analgesiegroep en er geen extra opioïden via epiduraal werd toegediend, was er geen klinisch relevant verschil tussen beide groepen. Op basis van deze gegevens is het waarschijnlijk dat patiënten die lidocaïne intraveneus krijgen waarschijnlijk eenzelfde hoeveelheid opioïden als doorbraakmedicatie benodigd zouden hebben ten opzichte van patiënten die een epiduraal met een niet-opioïde krijgen.

Het risico op hartritmestoornissen kwam uit op een zeer lage bewijskracht, vanwege het risico op bias en om dat maar twee studies met weinig deelnemers werden geïncludeerd.

Het risico op hypotensie werd niet onderzocht in de geïncludeerde studies.

Voor lidocaïne-geïnduceerde neurotoxiciteit kwamen we uit op een lage bewijskracht. Voor de andere bijwerkingen waren ook geen klinisch relevante verschillen gevonden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er zijn geen evaluaties gedaan met betrekking tot de aanvaardbaarheid, implementatie en haalbaarheid van toediening van lidocaïne.

- Lidocaïne vs. standaardzorg (zonder epiduraal)

De haalbaarheid en aanvaardbaarheid zal niet beperkt zijn, gezien het weinig extra belasting vraagt en binnen standaardzorg van de anesthesiologie valt. Lidocaïne is een van de meest gebruikte lokaal anesthetica, hierdoor is er al veel kennis en ervaring bekend onder anesthesiologie-personeel. Hoewel bekend, zal niet in elke kliniek lidocaïne intraveneus worden toegediend. Gezien de huidige literatuur zal lidocaïne tot einde van de operatie of nog op de verkoeverkamer worden toegediend. Anesthesiologiepersoneel is vertrouwd met het toedienen van intraveneuze medicatie. Daarnaast zijn de materialen hiervoor, zoals bijvoorbeeld een infuuspomp en spuiten, aanwezig op de operatiekamer. Als het in een kliniek nog niet gebruikelijk is om lidocaïne intraveneus toe te dienen zal een korte scholing voldoende zijn.

Als in specifieke gevallen (bijvoorbeeld patiënten met risicofactoren voor chronische post-chirurgische pijn) lidocaïne nog na de verkoever-periode wordt toegediend, zal dit op een afdeling moeten worden gedaan waar het personeel geschoold is in het herkennen en behandelen van Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST). In een practice guideline over toediening van lidocaïne wordt tevens geadviseerd dat patiënten ECG-monitoring krijgen (Foo, 2021). Een recente veiligheidsanalyse van 4483 patiënten die zonder ECG-monitoring lidocaïne kregen toegediend op de verpleegafdeling concludeert dat dit veilig is (n=1 serious event). Verpleegkundigen kregen een training in LAST, volgden een vast algoritme voor patiëntmonitoring en er waren gestandaardiseerde dosisregimes voor lidocaïne (Miller 2022). Lidocaïne vertoont na 24 uur toediening een tragere klaring, waardoor de dosering met 50% naar beneden aangepast dient te worden (Le Lorier, 1977).

Bij combinatie met andere locoregionale technieken is terughoudendheid geboden om geen toxische lokaal anestheticaspiegels te induceren, afhankelijk van welke techniek en bijbehorende benodigde dosering lokaal anestheticum. Zo zal een combinatie met spinale anesthesie weinig kans geven op toxisch plasmaspiegels; maar een field blok wel, hierbij dient een window van 4 uur aangehouden te worden tussen blok en lidocaïne i.v. toediening.

Lidocaïne geeft weinig extra belasting voor een patiënt die anesthesie ondergaat voor een operatie. Er zal een infuus nodig zijn voor toediening van lidocaïne, welke sowieso bij anesthesie geplaatst zal worden. Daarnaast geeft toediening van lidocaïne weinig bijwerkingen en kan de pijnbehandeling geoptimaliseerd worden, wat in het voordeel is voor de patiënt.

Er zal minimale extra tijd nodig zijn voor toediening van lidocaïne, voor zowel personeel als patiënt (optrekken spuiten voor bolus en continue infusie; toediening en registratie hiervan).

- Lidocaïne vs. epidurale pijnbestrijding

Lidocaïne levert enkele praktische voordelen op ten aanzien van een epiduraal: minder tijd nodig voor toediening, minder belasting voor een patiënt, en lidocaïne kan worden toegediend als er contra-indicaties zijn voor een epiduraal (zoals infectie, stollingsproblematiek, hemodynamische instabiliteit). Epidurale analgesie is een invasievere pijnbehandeling waarbij er een hogere incidentie is van hypotensie, er extra postoperatieve controles nodig zijn door het personeel (vaak APS-team) van de epidurale katheter (Popping, 2008), en er kans is op ernstige neurologische schade (1 op 1000-6000).

Daar staat tegenover dat de pijnbehandeling bij lidocaïne minder effectief kan zijn, waardoor er meer opioïden postoperatief nodig zijn en hierbij meer kans op bijwerkingen van de opioïden en tijdsbelasting van registratie opioïden. Zoals uit de literatuuranalyse blijkt is de bewijskracht voor de effectiviteit t.o.v. epiduraal nu beperkt, maar toekomstige trials met meer chirurgische patiënten zouden hier verandering in kunnen brengen. Het gebruik van opioïden als doorbraakmedicatie lijkt bij patiënten die lidocaïne intraveneus kregen niet meer te zijn dan de patiënten met epidurale analgesie.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is het belangrijk om een adequate pijnstilling postoperatief te hebben met zo min mogelijk bijwerkingen. Toevoeging van lidocaïne aan standaardzorg (of in vergelijking met epiduraal) geeft een niet klinisch relevante vermindering van pijnscores en opioïdengebruik rondom de operatie, maar kan het optreden van chronische pijn verminderen.

Het aantal bijwerkingen was laag in de gegeven doseringen van lidocaïne, dus toediening lijkt veilig te zijn, zeker gezien patiënten op de operatiekamer en verkoever continue monitoring hebben van hun vitale waarden.

Bij de keuze lidocaïne of epiduraal zal met de patiënt de hierboven beschreven effecten op pijn, bijwerkingen en complicaties van beide technieken moeten worden besproken, zodat voor de individuele patiënt de juiste afwegingen worden gemaakt.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De algehele kosteneffectiviteit van lidocaïne intra-operatief zijn nog niet in kaart gebracht. Lidocaïne is een goedkoop medicijn. Uitgaande van een standaarddosering lidocaïne zal de totale tijd van het klaarmaken en toedienen van een extra middel iets langer zijn. Lidocaïne is een middel dat al op de operatiekamer wordt toegediend. Er is daardoor geen extra scholing of kwalificatie van personeel nodig. Als er minder opiaten perioperatief of kort postoperatief gegeven worden, zal dat administratietijd schelen die verbonden is aan de opiumwetgeving. Waarschijnlijk zal de implementatie van lidocaïne tot een vergelijkbare perioperatieve tijdsbesteding leiden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Toevoeging van lidocaïne in een multimodale analgesiesetting geeft slechts een beperkte vermindering van de pijnscores en opiaatgebruik na een operatie. In deze richtlijn zijn alle operaties samengevoegd, maar bij subgroep-analyses uitgevoerd door Weibel (2018) kwam geen verschil tussen specifieke chirurgische procedures uit of door dosering (<2 mg/kg/uur en >2 mg/kg/uur).

Er was redelijke bewijskracht van de huidige onderzoeken dat lidocaïne het optreden van chronische pijn kan verminderen.

Lidocaïne geeft een laag risico op extra bijwerkingen, is goedkoop en past binnen de huidige praktijk. Gebruikelijke dosering zijn een bolus van 1,5 mg/kg rondom start anesthesie, gevolgd door een continue dosering van 1,5 mg/kg/uur tot het einde van de operatie.

Lidocaïne heeft ten opzichte van epidurale analgesie een vergelijkbaar of mogelijk minder effect op het verlagen van pijnscores en opiaatgebruik op 24 - 48 uur na de operatie. Daartegenover staat dat lidocaïne enkele praktische voordelen heeft: minder tijd nodig voor toediening, minder belasting voor een patiënt, en lidocaïne kan worden toegediend als er contra-indicaties zijn voor een epiduraal. Daarnaast is epidurale analgesie een meer invasievere pijnbehandeling waarbij er mogelijk een hogere incidentie is van hypotensie, er extra postoperatieve controles nodig zijn door het personeel, en er kans is op ernstige neurologische schade.

Bij de keuze lidocaïne of epiduraal zal de behandelaar in samenspraak met de patiënt hierin een afweging moeten maken.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Multimodale pijnbestrijding wordt intra-operatief ingezet om via verschillende aangrijpingspunten op de pijnverwerking een zo optimaal mogelijke pijnstilling met zo weinig mogelijk bijwerkingen te bewerkstelligen en de nood aan opiaten te verlagen. Lidocaïne is een lokaal anestheticum met anti-inflammatoire eigenschappen dat intraveneus kan worden toegediend in het kader van multimodale analgesie bij operaties. Het wordt met name toegediend bij abdominale chirurgie (Dunn, 2017), in deze module zijn alle operaties meegenomen. Lidocaïne kan worden gegeven als aanvulling op andere analgetica of in plaats van epidurale pijnbestrijding. De vraag is of lidocaïne hierbij postoperatieve pijn en het gebruik van rescue medicatie kan reduceren.

Conclusies

PICO 1. Lidocaine vs. standard care (without epidural)

Postoperative pain

|

Low GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at PACU arrival when compared to standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Ghimire, 2020; Rekatsina, 2021; Sherif, 2017; Weibel, 2018. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine likely results in little to no difference in postoperative pain at 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours post-surgery when compared with standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Ghimire, 2020; Ho, 2018; Lv, 2021; Peng, 2021; Rekatsina, 2021; Sherif, 2017; Song, 2017; Wang, 2021; Weibel, 2018; Xu, 2021. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine likely reduces chronic pain when compared with standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Choi, 2016b; Ghimire, 2020; Grigoras, 2012; Kendall, 2018; Kim, 2017; Terkawi, 2014. |

Postoperative opioid consumption

|

Moderate GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine likely results in little to no difference in postoperative opioid consumption in PACU, in 24 hours post-surgery and in the total postoperative period when compared with standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Ghimire, 2020; Herzog, 2020; Kendall, 2018; Rekatsina, 2021; Sherif, 2017; Song, 2017; Terkawi, 2014; Weibel, 2018; Xu, 2021. |

Adverse events

|

Low GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine may result in little to no difference in neurotoxicity when compared with standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Ho, 2018; Weibel, 2018. |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine likely results in little to no difference in the incidence of arrhythmia and hypotension when compared with standard care in surgical patients.

Source: Ghimire, 2020; Rekatisina, 2021; Song, 2017; Weibel, 2018. |

PICO 2. Lidocaine vs. epidural analgesia

Postoperative pain

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of perioperative lidocaine on postoperative pain at PACU arrival and at 6 hours post-surgery when compared to epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: Kutay Yazici, 2021. |

|

Low GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine may result in little to no difference in pain reduction at 12, 24 and 48 hours post-surgery when compared with epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: Kuo, 2006; Kutay Yazici, 2021; Staikou, 2014; Swenson, 2010; Wongyingsinn, 2011. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of perioperative lidocaine on chronic pain when compared with epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: - |

Postoperative opioid consumption

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of perioperative lidocaine on postoperative opioid consumption in PACU when compared with epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: - |

|

Low GRADE |

Perioperative lidocaine may result in little to no difference in opioid consumption in 24 hours post-surgery and in the total postoperative period when compared with epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: Kutay Yazici, 2021; Staikou, 2014; Wongyingsinn, 2011. |

Adverse events

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of perioperative lidocaine on the incidence of arrhythmia and neurotoxicity when compared with epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: Kuo, 2006; Staikou, 2014; Swenson, 2010. |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of perioperative lidocaine on hypotension when compared with epidural analgesia in surgical patients.

Source: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Weibel (2018) performed a systematic search until January 2017 in the databases of Medline (Ovid), EMBASE (Embase), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and CINAHL (EBSCO). They included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the effect of perioperative lidocaine infusions versus no treatment, placebo treatment or versus epidural analgesia. A total of 68 RCTs were included. For these RCTs, the assessment of the risk of bias was performed by Weibel (2018).

The RCTs included data on 4,525 participants, 2,254 of which received intravenous lidocaine and 2,271 received a control treatment.

Table 1 provides an overview of the main study characteristics of the RCTs by Weibel and additional recently published RCTs (a total of 78 studies).

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

|

Author, year |

N (I/C) |

Surgical procedure |

Lidocaine intervention |

Control |

Start infusion¹ |

End infusion |

|

|

|

|

Bolus dose |

Infusion dose |

|

|||

|

25/ 25 |

Laparoscopic colectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

30/ 30 |

Abdominal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

1 hr after the end of surgery |

|

|

44/ 46 |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

3 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

10/ 10 |

Cholecystectomy |

100 mg |

120 mg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

40/ 40 |

Spine surgery |

1 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

After induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

30/ 30 |

Breast plastic surgeries |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

No treatment |

30 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

28/ 28 |

Elective total thyroidectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

41/ 43 |

Thyroidectomy |

2 mg/kg |

3 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

Extubation |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Thoracic surgery |

No bolus |

1.98 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

12/ 12 |

Laparoscopic fundoplication |

1 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

24 hr after start of continuous infusion |

|

|

31/ 32 |

Outpatient laparoscopic surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

24/ 26 |

Laparoscopic |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

39/ 40 |

Laparoscopic sterilisation in women |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

30 mins after arrival at PACU |

|

|

45/ 45 |

Caesarean delivery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

60 mins after end of surgery |

|

|

57/ 58 |

Spine surgery |

No bolus |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

Discharge from the PACU or a maximum of 8 hr |

|

|

31/ 31 |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

Ghimire 2020³ |

32/ 32 |

Laparoscopic surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

After tracheal extubation |

|

17/ 19 |

Surgery for breast cancer |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

60 mins after end of surgery |

|

|

18/ 20 |

Radical retropubic prostatectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

60 mins after end of surgery |

|

|

31/ 29 |

Colorectal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

120 mg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

4 hr |

|

|

Herzog 2020³ |

29/ 29 |

Robotic colorectal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

2 hr |

|

Ho |

28/ 29 |

Open colorectal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

60 mg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

48 hr postop |

|

44/ 45 |

CABG |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.8 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

After induction |

Up to 48 hr in the ICU |

|

|

30/ 30 |

Lumbar discectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

Until 10 mins after extubation |

|

|

30/ 30 |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

End of first postop hr, max. 180 mins |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Laparoscopic colectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr intraop and 1.33 mg/kg/h for 24 hr |

Saline |

At induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

32/ 32 |

Inguinal herniorrhaphy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

10/ 10 |

CABG |

3 mg/kg |

3 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

Unclear |

|

|

Kendall 2018³ |

74/ 74 |

Breast Cancer Surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

1 hr after end of surgery |

|

22/ 21 |

Laparoscopic appendectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

17/ 17 |

Laparoscopic gastrectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Preop |

End of surgery |

|

|

Kim 2014a² |

36/ 38 |

CABG |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

No treatment |

Before induction |

24 hr after end of surgery |

|

Kim 2014b² |

32/ 36 |

Laparoscopic colectomy |

1 mg/kg |

1 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

After 24 hr |

|

Kim |

25/ 26 |

Elective one‐level laminectomy and discectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Preop |

End of surgery |

|

Kim |

39/ 39 |

Elective breast cancer surgery |

2 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

After induction |

End of surgery |

|

20/ 20 |

Major abdominal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

1 hr after end of surgery |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Surgery for colon cancer |

2 mg/kg |

3 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

25/ 24 |

Outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

No treatment |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Laparoscopic prostatectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

50/ 49 |

Off‐pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

Lv |

45/ 45 |

Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

15 min before induction |

End of surgery |

|

33/ 34 |

Prostatectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr during surgery, |

Saline |

Before induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

28/ 30 |

Hip |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

1 hr after end of surgery |

|

|

114/ 127 |

Cardiac surgery |

1 mg/kg |

240 mg for 1 hr, |

Saline |

After induction |

48 hr postop |

|

|

29/ 27 |

Outpatient surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

After induction |

1 hr after arrival in the PACU |

|

|

28/ 27 |

Cardiac surgery |

1 mg/kg |

240 mg over the first hr and |

Saline |

At induction |

48 hr postop |

|

|

81/ 77 |

CABG |

1 mg/kg |

120 mg/hr for 2 hr, and 60 mg/hr thereafter |

Saline |

At induction |

Total of 12 hours |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Hysterectomy |

No bolus |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

24/ 24 |

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

After induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

21/ 22 |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

3 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

1 hr after end of surgery |

|

|

40/ 40 |

Supratentorial tumour surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

After induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

Peng |

40/ 40 |

Hysteroscopic surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

Rekatsina 2021³ |

29/ 26 |

Abdominal gynecological surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

15/ 15 |

Cholecystectomy |

100 mg |

180 mg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

40/ 40 |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

2 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

39/ 39 |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

1 hr after surgery |

|

|

Sherif 2017³ |

46/ 49 |

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy |

2 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

14/ 13 |

VATS |

1.5 mg/kg |

180 mg/hr if TBW was more than 70 kg or 120 mg/hr if weight was less than 70 kg |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

40/ 40 |

Ophthalmologic surgeries |

No bolus |

2.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

NA |

Intraoperatively |

|

|

Song 2017³ |

36/ 35 |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

67/ 67 |

Open abdominal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

1 hr after surgery |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Large bowel surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

Before skin suturing |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Tonsillectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr over 6 hr and |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

24 hr |

|

|

37/ 34 |

Breast cancer surgery |

1.5 mg/kg, max. 150 mg |

2 mg/kg/h, max 200 mg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

2 hr after arrival in PACU or at discharge from PACU |

|

|

30/ 30 |

Laparoscopic colon resection |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr during surgery, 1 mg/ |

Saline |

Before induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

18/ 20 |

Cholecystectomy |

100 mg |

120 mg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

43/ 45 |

CABG |

1.5 mg/kg, second dose (4 mg/kg) was administered to the priming solution |

240 mg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

15/ 15 |

Hysterectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

Discharge from the operating room |

|

|

Wang 2021³ |

49/ 50 |

Upper airway surgery |

2 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

37/ 38 |

Radical retropubic prostatectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

Before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

25/ 25 |

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

No bolus |

3 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

30 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

32/ 32 |

Laparoscopic transperitoneal renal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr during surgery, |

Saline |

At induction |

24 hr postop |

|

|

60/ 60 |

Abdominal hysterectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

Wound closure |

|

|

Xu |

60/ 60 |

Laparoscopic hysterectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

10 mins before induction |

30 mins before the end of surgery |

|

24/ 26 |

Laparoscopic |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

30/ 30 |

Transabdominal hysterectomy |

2 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

20 mins before induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

17/ 19 |

Subtotal gastrectomy |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

|

20/ 20 |

Laparotomy |

1.0 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/hr |

Saline |

At induction |

End of surgery |

|

¹’At induction’ was defined as admission between 10 minutes before and 5 minutes after induction

²RCTs included in the systematic review by Weibel (2018)

³Additional RCTs, not included in the systematic review by Weibel (2018)

CABG, Coronary artery bypass graft; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; NA, not available; TWB, total body weight; VATS, Video-assisted thoracic surgery.

In 73 studies i.v. lidocaine administration was initiated with a bolus dose of 1 mg/kg to 3 mg/kg of body weight or 100 mg lidocaine, 1.5 mg/kg being the most common dose, used in 75% of the included trials. In five studies lidocaine administration was started without a bolus dose.

In 41 studies, the continuous infusion of lidocaine was administered with a rate of ≥ 2 mg/kg/h, whereas an infusion rate of < 2 mg/kg/h was used in another 27 studies. In 9 trials, a higher infusion dose (≥ 2 mg/kg/h) was used during the first study period followed by continuous infusion < 2 mg/kg/h during the second study period. One study used different rates for a high versus low total body weight (Slovack 2015).

Results

If applicable, means and standard deviations were estimated from the medians and interquartile ranges using the method by Hozo (2005). Pain scores on a 100-point scale were divided by 10 if the data could be pooled.

PICO 1. Lidocaine vs. standard care

1. Postoperative pain

1.1 Postoperative pain at PACU arrival

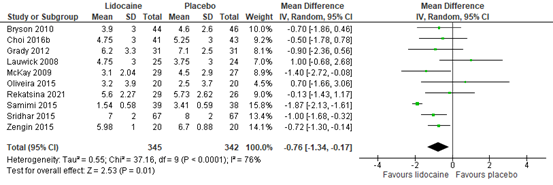

Pain scores at PACU arrival were reported by ten RCTs. The results are presented in figure 1. A mean difference (MD) of - 0.76 (95% CI -1.34, -0.17) was found in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Postoperative pain at PACU arrival

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, six RCTs presented pain scores at PACU arrival in figures. Five RCTs reported data in favour of lidocaine and 1 had similar data for both groups. This is in line with the pooled data. Details are described below.

Baral (2010) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. The pain score was considerably higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 4 vs. 1.5).

Choi (2016a) reported mean VAS pain scores (scale 0-100) in figures. The pain score was considerably higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 29 vs. 20).

Dewinter (2016) reported mean NRS scores for postoperative pain in PACU in figures. In both groups, the pain score was approximately 2.

Ghimire (2020) reported median NRS scores at rest for postoperative pain in PACU in figures. The pain score was higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 1 vs. 0).

Saadawy (2010) reported mean VAS scores for abdominal pain and shoulder pain in figures. No difference was found between the groups for postoperative shoulder pain. For abdominal pain, the VAS score of the control group was higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 3.5 vs. 2.8).

Sherif (2017) reported mean NRS scores in figures. At PACU arrival, the control group had considerably higher scores than the lidocaine group (approximately 6.5 vs. 3.9).

1.2 Postoperative pain at 6 hours

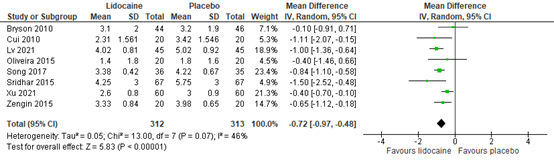

Pain scores at 6 hours post-surgery were reported by eight RCTs. The results are presented in figure 2. The MD was -0.72 (95% CI -0.97, -0.48) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Postoperative pain at 6 hours post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, seven RCTs presented pain scores at 6 hours post-surgery in figures. Four RCTs reported data in favour of lidocaine, 1 reported data in favour of the control group and 2 RCTs had similar data for both groups. This is in line with the pooled data. Details are described below.

Dale (2016) reported mean NRS (0-10) scores at rest in figures. At 6 hours post-surgery, the lidocaine group reported a higher pain score than the control group (approximately 5.4 vs. 2.9).

Farag (2013) reported mean VRS scores in figures. At 4 to 6 hours post-surgery, the lidocaine and control group reported similar pain scores (both approximately 5).

Ghimire (2020) reported median NRS scores at rest for postoperative pain at 6 hours in figures. The pain scores in both groups were similar (both between 1 and 2).

Saadawy (2010) reported mean VAS scores for abdominal pain and shoulder pain in figures. No difference was found between the groups for postoperative shoulder pain. For abdominal pain, the VAS score of the control group was higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 5.4 vs. 2.3).

Striebel (1992) reported pain scores in figures. At 6 hours, the control group had higher VAS scores than the lidocaine group (approximately 4 vs. 2.8).

Weinberg (2016) reported VAS scores at rest in figures. The control group had higher VAS scores than the lidocaine group (approximately 3.2 vs. 2.1).

Wuethrich (2012) reported mean NRS (0-10) scores in figures. At 6 hours post-surgery, pain scores were higher in the control group than the lidocaine group (2 vs. 1).

1.3 Postoperative pain at 12 hours

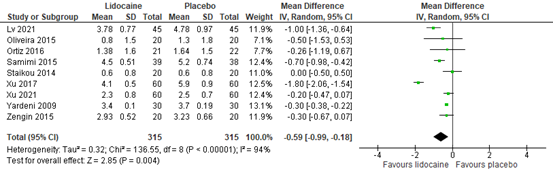

Pain scores at 12 hours post-surgery were reported by nine RCTs. The results are presented in figure 3. The MD was -0.59 (95% CI -0.99, -0.18) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Postoperative pain at 12 hours post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, seventeen RCTs presented pain scores at 12 hours post-surgery in different ways, mostly in figures. Fifteen RCTs reported data in favour of lidocaine, 1 in favour of the control and 1 had similar data for both groups. This is in line with the pooled data. Details are described below.

Ahn (2015) reported mean VAS (0-100) scores in figures. The control group had higher pain scores than the lidocaine group at 12 hours post-surgery (approximately 31 vs. 24).

Baral (2010) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. The pain score was a bit higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 3.2 vs. 2.6).

Choi (2016a) reported mean VAS pain scores (scale 0-100) in figures. The pain score was higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 19 vs. 16).

Dale (2016) reported mean NRS (0-10) scores at rest in figures. At 12 hours post-surgery, the lidocaine group reported a higher pain score than the control group (approximately 4.1 vs. 1.3).

Ghimire (2020) reported median NRS scores at rest for postoperative pain at 12 hours in figures. The pain score was higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 1.5 vs. 1).

Ho (2018) reported median NRS scores in figures. At 12 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in both groups were similar (approximately 4).

Kang (2011) reported mean VAS scores (0-100) in figures. At 12 hours post-surgery, the pain scores were higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 26 vs. 21).

Kim (2011) reported mean VAS (0-100) pain scores in figures. The control group had higher pain scores than the lidocaine group at 12 hours post-surgery (approximately 31 vs. 23).

Kim (2014c) reported VAS (0-100) pain scores in figures. The control group had higher pain scores than the lidocaine group at 12 hours post-surgery (approximately 23 vs. 17).

Kuo (2006) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. At 12 hours post-surgery, the control group had slightly higher pain scores than the lidocaine group (approximately 5 vs. 4.5).

Saadawy (2010) reported mean VAS scores for abdominal pain and shoulder pain in figures. For shoulder pain, the control group had higher pain scores than the lidocaine group (approximately 4.7 vs. 2.6). For abdominal pain, the pain scores of the control group were also higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 4.3 vs. 2.0).

Sherif (2017) reported mean NRS scores in figures. At 12 hours post-surgery, the control group had a higher pain score than the lidocaine group (approximately 3.4 vs. 2.4).

Tikuisis (2014) reported mean VAS scores at rest without standard deviations. At 12 hours post-surgery, the control group had a pain score of 3.8 and the lidocaine group 2.8.

Weinberg (2016) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. The pain scores in the control group were slightly higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 1.7 vs. 2.3).

Wu (2005) reported mean VAS scores at 12 hours post-surgery in figures. The pain scores in the control group were slightly higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 2.8 vs. 2.5).

Yang (2014) reported mean VAS scores in figures. The pain scores I the control group were slightly higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 3.2 vs. 2.5).

Yon (2014) reported mean VAS (0-100) scores at 12 hours post-surgery in figures. The pain scores in the control group were slightly higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 42 vs. 38).

1.4 Postoperative pain at 24 hours

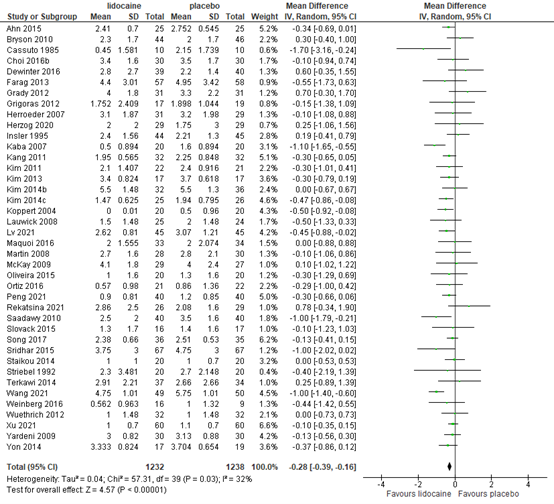

Pain scores at 24 hours post-surgery were reported by 40 RCTs. The results are presented in figure 4. The MD was -0.28 (95% CI -0.39, -0.16) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, three RCTs presented pain scores at 24 hours post-surgery in different figures. All three RCTs reported data in favour of lidocaine. This is in line with the pooled data. Details are described below.

Choi (2016a) reported mean VAS pain scores (scale 0-100) in figures. The pain score was higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 16 vs. 14).

Ghimire (2020) reported median NRS scores at rest for postoperative pain 24 hours in figures. The pain score was higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 1.5 vs. 1).

Ho (2018) reported median NRS scores in figures. At 24 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in the control group were slightly higher than the lidocaine group (approximately 4.2 vs. 3.2).

1.5 Postoperative pain at 48 hours

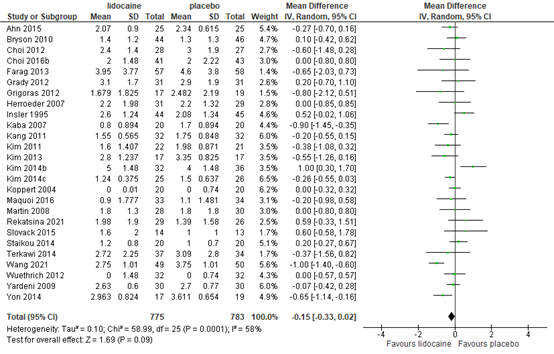

Pain scores at 48 hours post-surgery were reported by 26 RCTs. The results are presented in figure 5. The MD was -0.15 (95% CI -0.33, 0.02) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Postoperative pain at 48 hours post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, three RCTs presented pain scores at 48 hours post-surgery in different ways. One RCT reported data in favour of lidocaine, 1 in favour of the control and 1 had similar data for both groups. These varied results are in line with the pooled data. Details are described below.

Choi (2016a) reported mean VAS pain scores (scale 0-100) in figures. The pain score was higher in the control group compared to the lidocaine group (approximately 11 vs. 9).

Ho (2018) reported median NRS scores in figures. At 48 hours post-surgery, the control group had slightly lower pain scores than the lidocaine group (approximately 2 vs. 3).

Sherif (2017) reported mean NRS scores in figures. At 48 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in both groups were similar (both between 5.5 and 6).

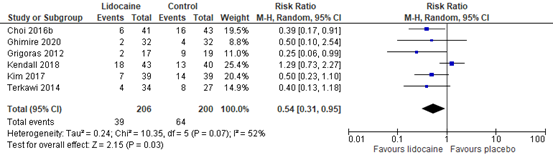

2. Chronic postoperative pain

Six RCTs reported chronic postoperative pain after surgery (minimum follow-up of three months). The results are presented in figure 6. The risk ratio (RR) is 0.54 (95% CI 0.31, 0.95) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 6. Chronic pain

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

3. Postoperative opioid consumption

All reported doses were converted to morphine milligram equivalents (MME) i.v.

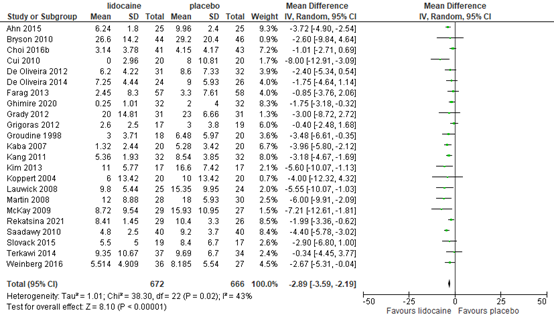

3.1 Postoperative opioid consumption in PACU

In total, 23 trials reported data on postoperative opioid consumption. Thirteen trials applied morphine for postoperative pain relief (Bryson 2010; Cui 2010; Farag 2013; Grady 2012; Grigoras 2012; Groudine 1998; Koppert 2004; Martin 2008; McKay 2009; Rekatsina 2021; Saadawy 2010; Slovack 2015; Weinberg 2016); 6 trials applied fentanyl (Ahn 2015; Choi 2016b; Kang 2011; Kim 2013; Lauwick 2008; Terkawi 2014; two hydromorphone (De Oliveira 2012; De Oliveira 2014); one tramadol (Ghimire 2020) and one piritramide (Kaba 2007).

The results are presented in figure 7. The MD was -2.89 (95% CI -3.59, -2.19) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 7. Postoperative opioid consumption in PACU

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

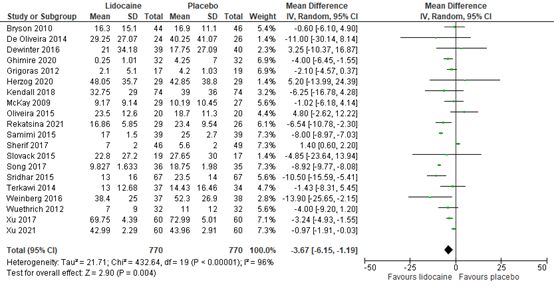

3.2 Postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours

Twenty RCTs reported data on postoperative opioid consumption. Twelve studies reported postoperative morphine consumption (Bryson 2010; Grigoras 2012; Herzog 2020; McKay 2009; Oliveira 2015; Rekatsina 2021; Samimi 2015; Sherif 2017; Slovack 2015; Sridhar 2015; Weinberg 2016; Wuethrich 2012), four fentanyl (Song 2017; Terkawi 2014; Xu 2017; Xu 2021), two tramadol (Dewinter 2016; Ghimire 2020), and one hydromorphone (De Oliveira 2014). One study did not report which opioid was used (Kendall 2018).

The results are presented in figure 8. The MD was -3.67 (95% CI -6.15, -1.19) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 8. Postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

3.3 Total postoperative opioid consumption

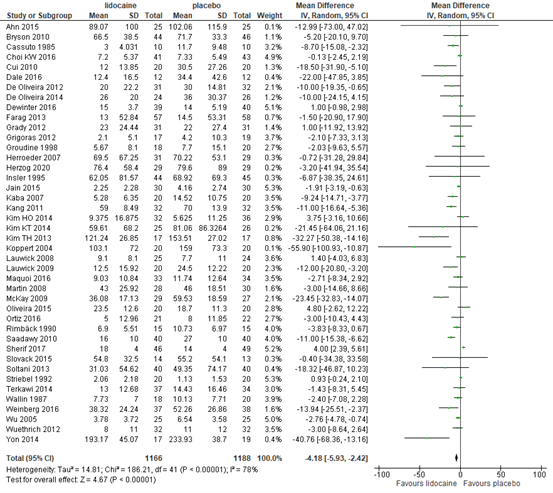

A total of 42 RCTs reported cumulative opioid consumption in the total postoperative period. Of all trials reporting data on postoperative opioid consumption, 18 trials applied morphine for postoperative pain relief (Bryson 2010; Cui 2010; Farag 2013; Grady 2012; Grigoras 2012; Groudine 1998; Herzog 2020; Koppert 2004; Lauwick 2009; Martin 2008; McKay 2009; Oliveira 2015; Ortiz 2016; Saadawy 2010; Sherif 2017; Slovack 2015; Weinberg 2016; Wuethrich 2012); 9 trials applied fentanyl (Ahn 2015; Choi 2016b; Dale 2016; Insler 1995; Kang 2011; Kim KT 2014; Kim 2013; Terkawi 2014; Yon 2014); seven trials applied meperidine/pethidine (Cassuto 1985; Kim HO 2014; Rimbäck 1990; Soltani 2013; Striebel 1992; Wallin 1987; Wu 2005); one hydromorphone (De Oliveira 2012); one trial offered tramadol (Dewinter 2016); one pentazocine (Jain 2015); one oxycodone (Lauwick 2008); and three piritramide (Herroeder 2007; Kaba 2007; Maquoi 2016). One study did not report which opioid was used (De Oliveira 2014).

The results are presented in figure 9. The MD was -4.18 (95% CI -5.93, -2.42) in favour of lidocaine. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 9. Postoperative opioid consumption in the total postoperative period

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

4. Adverse events

Adverse events are divided into cardiotoxicity, and neurotoxicity. In addition, several studies reported that there were no signs of lidocaine toxicity in either of the groups (Ahn, 2015; Cassuto, 1985; Choi, 2016ab; Cui, 2010; De Oliveira, 2012; De Oliveira, 2014; Dewinter, 2016; El-Tahan, 2009; Grigoras, 2012; Groudine, 1998; Kim, 2011; Kim, 2013; Kim, 2014abc; Martin, 2008; Ortiz, 2016; Peng, 2016; Rimback, 1990; Samimi, 2015; Striebel, 1992; Terkawi, 2014; Tikuisis, 2014; Wu, 2005; Wuethrich, 2012; Yang, 2014).

4.1 Cardiotoxicity

Cardiotoxicity was divided into arrhythmias (i.e., bradycardia and/or tachycardia) and hypotension.

4.1.1 Arrhythmia

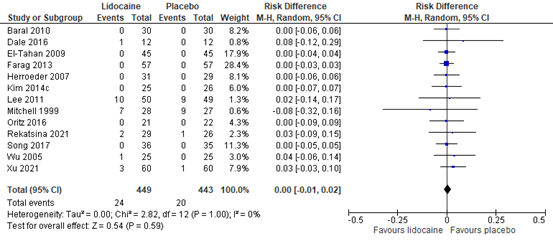

Thirteen RCTs reported the incidence of arrhythmia. The results are presented in figure 10. The risk difference (RD) is 0.00 (95% CI -0.01, 0.02). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 10. Incidence of arrhythmia

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

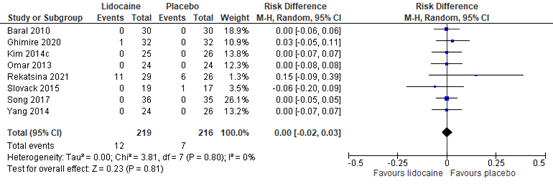

4.1.2 Hypotension

Eight RCTs reported the incidence of hypotension. The results are presented in figure 11. The risk difference (RD) is -0.00 (95% CI -0.02, 0.03). This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 11. Incidence of hypotension

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

4.2 Neurotoxicity

Ten RCTs reported signs of possible neurotoxicity.

Baral (2010) reported no cases of perioral numbness in both the lidocaine and the control group.

Cassuto (1985) reported light-headedness in 1 patient in the lidocaine group and 1 patient in the control group.

Choi (2012) reported dizziness at 24 hours (1 versus 3 patients in lidocaine and control group, respectively), 48 hours (1 versus 2 patients in lidocaine and control group, respectively), and 72 hours (1 patient in both groups).

Dale (2016) reported 1 case of perioral paresthesia in the lidocaine group versus 0 in the control group.

El-Tahan (2009) reported no cases in either group of light-headedness, perioral numbness, or seizures.

Jain (2015) reported 3 patients with drowsiness in the lidocaine group and 0 in the control group. No patients had perioral numbness. The incidence of light-headedness was comparable in both groups.

Koppert (2004) found comparable incidence of drowsiness and light-headedness in both groups.

McKay (2009) reported 1 case of dizziness and visual disturbance in the lidocaine group versus none in the control group.

Wallin (1987) reported 2 cases of drowsiness in the lidocaine group and none in the control group.

Weinberg (2016) reported dizziness in 14 versus 20 patients and perioral numbness in 2 and 2 patients in the lidocaine and control group, respectively.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcome measures started as high because all included studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at PACU arrival was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); wide confidence intervals (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 6 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 12 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 48 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure chronic pain was downgraded by 1 level because of wide confidence intervals and a low number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in PACU was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure opioid consumption in total postoperative period was downgraded by 1 level because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure arrhythmia was downgraded by 1 level because of a very low number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension was downgraded by 1 level because of a very low number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is moderate.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure neurotoxicity was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1), and a very low number of events (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

PICO 2. Lidocaine vs. epidural analgesia

Description of studies

Five RCTs were included that compared perioperative lidocaine intravenous with epidural analgesia. In table 2, an overview of these studies is presented.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

|

Author, year |

N (I/C) |

Surgical procedure |

Lidocaine intervention |

Epidural Control |

Start infusion¹ |

End infusion |

|

|

|

|

Bolus dose |

Infusion dose |

|

|||

|

Kuo 2006 |

20/ 20 |

Surgery for colon cancer |

2 mg/kg |

3 mg/kg/h |

Thoracic epidural with lidocaine 2 mg/kg for 10 min, then 3 mg/kg/h + an equal volume of saline i.v. |

30 mins pre-op |

End of surgery |

|

Kutay Yazici 2021 |

25/ 25 |

Gynecologic cancer surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

1.5 mg/kg/h

Patients received postoperative PCA (morphine) |

Intraoperative i.v. saline infusion + intraoperative remifentanil infusion 0.1-0.2 µg/kg/min + postoperative PCA with epidural bupivacaine HCl (placed at Th 9-12) |

At induction |

24 hrs postop |

|

Staikou 2014 |

20/ 20 |

Major large bowel surgery |

1.5 mg/kg |

2 mg/kg/h + Epidural bolus ropivacaine 20 mg and morphine 1 mg postoperative |

Lumbar epidural with 2% lidocaine intraoperative+ Epidural bolus ropivacaine 20 mg and morphine 1 mg postoperative |

Pre-induction |

End of surgery |

|

Swenson 2010 |

21/ 21 |

Colon resection |

None |

2 mg/min for <70 kg and 3 mg/min for >70 kg. Reduced due to reaching toxic levels (1 mg/min for <70 kg and 2 mg/min for >70 kg |

Thoracic epidural with bupivacaine 0.125% and hydromorphone 6 µg/mL were started 1 h after the end of surgery |

After induction |

Day after return of bowel function (mean: 3 days) |

|

Wongyingsinn 2011

|

30/ 30 |

Laparoscopic colorectal surgery |

1.5 mg/kg (maximum 100 mg) |

2 mg/kg/h intraoperative, 1 mg/kg/h postoperative |

Thoracic epidural with bupivacaine 0.25% 5 to 8 mL/h started preoperative. Continuous epidural analgesia with bupivacaine 0.1% and morphine 0.02 mg/mL started post-op |

Pre-induction |

48 hrs post-op |

PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

1. Postoperative pain

1.1 Postoperative pain at PACU arrival

Kutay Yazici (2021) reported VAS scores at 15 minutes post-surgery. In the lidocaine group, the mean pain score was 3.8 (SD 0.1) and in the epidural group 3.2 (SD 0.1).

1.2 Postoperative pain at 6 hours

Kutay Yazici (2021) reported VAS scores at 6 hours post-surgery. In the lidocaine group, the mean pain score was 2.4 (SD 0.1) and in the epidural group 2.2 (SD 0.1).

Swenson (2010) reported median pain scores in figures at the day of the surgery. The pain score was higher in the lidocaine than the epidural group (approximately 4.7 vs. 3.2).

1.3 Postoperative pain at 12 hours

Three RCTs reported postoperative pain at 12 hours post-surgery.

Kuo (2006) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. At 12 hours post-surgery, the pain scores for the lidocaine and the TEA group were comparable (both between 2.5 and 3).

Kutay Yazici (2021) reported VAS scores at 12 hours post-surgery. In the lidocaine group, the mean pain score was 1.8 (SD 0.9) and in the epidural group 1.8 (SD 0).

Staikou (2014) reported mean VAS scores at rest. At 12 hours post-surgery, the pain scores for the lidocaine group were 0.6 (SD 0.8) and in the epidural group 0.6 (SD 0.8). The MD was 0.00 (95% CI -0.50, 0.50).

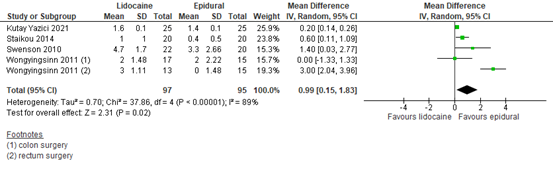

1.4 Postoperative pain at 24 hours

Four RCTs reported postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery. Wongyingsinn (2011) compared two types of epidural analgesia to lidocaine. The results are presented in figure 12. The MD is 0.99 (95% CI 0.15, 1.83) in favour of epidural analgesia. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 12. Postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, two studies presented pain scores at 24 hours post-surgery in different ways.

Kuo (2006) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. At 24 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in both groups were similar (both around 2.8).

Swenson (2010) reported pain scores in figures after the first operative day. For both groups, the pain scores were similar (both around 2.5).

1.5 Postoperative pain at 48 hours

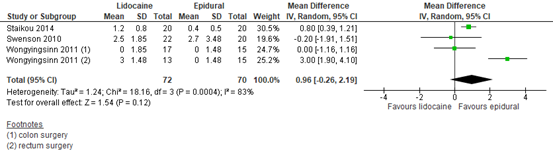

Three RCTs reported postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery. Wongyingsinn (2011) compared two types of epidural analgesia to lidocaine. The results are presented in figure 13. The MD is 0.96 (95% CI -0.26, 2.19) in favour of epidural. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Figure 13. Postoperative pain at 48 hours post-surgery

Z: p-value of the pooled effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistic heterogeneity; CI: Confidence Interval

In addition to the pooled data, two studies presented pain scores at 48 hours post-surgery in different ways.

Kuo (2006) reported mean VAS scores at rest in figures. At 48 hours post-surgery, the pain scores in both groups were similar (both around 2.3).

Swenson (2010) reported pain scores in figures after the second operative day. For both groups, the pain scores varied between 1.5 and 2.

2. Chronic pain

No studies were included comparing lidocaine to epidural analgesia and reporting chronic pain.

3. Postoperative opioid consumption

3.1 Postoperative opioid consumption in PACU

No studies were included comparing lidocaine to epidural analgesia and reporting postoperative opioid consumption in PACU.

3.2 Postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours

Kutay Yazici (2021) reported the total postoperative morphine consumption in 24 hours, including morphine in postoperative patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). The lidocaine group received 18 mg (SD 3) and the epidural group 0.88 (SD 0.26). However, in the lidocaine group, the patients received PCA with morphine, in the epidural group they did not. The rescue doses morphine provided were similar between both groups: 0.61 mg (SD 0.22) in the lidocaine group and 0.88 mg (SD 0.26) in the epidural group. This difference in rescue medication is not clinically relevant.

Wongyingsinn (2011) reported postoperative morphine consumption in 24 hours. The lidocaine group received a median of 25.5 mg (interquartile range (IQR) 17-41) via PCA and the epidural group 3.8 mg (IQR 3.3-4.9) morphine via epidural. This difference is considered clinically relevant in favour of the epidural group.

3.3 Opioid consumption in total postoperative period

Staikou (2014) reported morphine consumption in the total postoperative period (48 hours). Both groups received morphine and ropivacaine via a patient-controlled epidural analgesia pump starting in PACU if analgesia was inadequate. The lidocaine group reported a mean postoperative morphine consumption of 2.72 mg (SD 1.01) and the epidural group 2.56 mg (SD 0.2). The MD is 0.16 (95% CI -0.29, 0.61) in favour of epidural analgesia. This difference is considered not clinically relevant.

Wongyingsinn (2011) reported postoperative morphine consumption in 48 hours. The lidocaine group received a median of 8.5 (IQR 0-31) via PCA and the epidural group 2.9 (IQR 2.0-3.5) morphine via epidural. This difference is considered not clinically relevant in favour of the epidural group.

Wongyingsinn (2011) also reported oral oxycodone consumption as breakthrough medication at 72 hours post-surgery. The lidocaine group received a median of 20.0 (IQR 20-32) mg and the epidural group 27.5 (IQR 20-35). This difference is favour of the intravenous lidocaine group was not considered clinically relevant.

4. Adverse events

Adverse events are divided into cardiotoxicity and neurotoxicity. In addition, two studies reported that there were no signs of lidocaine toxicity in either of the groups (Kutay Yazici, 2021; Wongyingsinn, 2011).

4.1 Cardiotoxicity

Cardiotoxicity was divided into arrhythmias and hypotension.

4.1.1 Arrhythmia

Kuo (2006) reported bradycardia in 3 out of 20 patients (15%) in the lidocaine group and 0 out of 20 in the epidural group.

Swenson (2010) reported arrhythmia in 1 out of 22 (4.5%) patients in the lidocaine group and 1 out of 20 (5%) patients in the epidural group.

4.1.2 Hypotension

No studies were included comparing lidocaine to epidural analgesia and reporting hypotension.

4.2 Neurotoxicity

Staikou (2014) reported 1 out of 20 patients (5%) with transient confusion in the lidocaine group and 0 out of 20 in the epidural group.

Swenson (2010) reported dizziness/light-headedness in 1 out of 21 patients (4.8%) in both groups.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding all outcome measures started as high, because the studies were RCTs.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at PACU arrival was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 6 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 12 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 24 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); the pooled data crossing the boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 48 hours post-surgery was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); the pooled data crossing the boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure chronic pain could not be graded, since no studies were included that reported this outcome measure.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in PACU could not be graded, since no studies were included that reported this outcome measure.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption in 24 hours was downgraded by 2 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -1). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure opioid consumption in total postoperative period was downgraded by 2 levels because of the number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure arrhythmia was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension could not be graded, since no studies were included that reported this outcome measure.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure incidence of neurotoxicity was downgraded by 3 levels because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence is very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following two questions: 1. What is the effectiveness of adding lidocaine intraoperatively to standard care (not epidural) in surgical patients on postoperative pain, adverse events and rescue analgesic consumption?

2. What is the effectiveness of adding lidocaine intraoperatively to standard care in comparison to an epidural in surgical patients on postoperative pain, adverse outcomes and rescue analgesic consumption?

PICO 1.

P (patients) patients undergoing a surgical procedure

I (intervention) intraoperative lidocaine i.v.

C (comparison) standard care

O (outcomes) postoperative pain (acute and chronic)

postoperative opioid consumption

adverse events (cardiotoxicity (hypotension, arrhythmia) and neurotoxicity (altered mental status, slurred speech))

PICO 2.

P (patients) patients undergoing a surgical procedure

I (intervention) intraoperative lidocaine i.v.

C (comparison) epidural analgesia

O (outcomes) postoperative pain (acute and chronic)

postoperative opioid consumption

adverse events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered postoperative pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and postoperative opioid consumption and adverse events as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Postoperative pain at rest: Validated pain scale (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) or Verbal Rating Scale (VRS)) at post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) arrival, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours post-surgery. Chronic postoperative pain: pain > 3 months, in line with the international association study of pain (IASP).

Postoperative opioid consumption was assessed in PACU, 24 hours post-surgery and total postoperative period.

Adverse events included cardiotoxicity (hypotension, arrhythmia) and neurotoxicity (altered mental status, slurred speech). The working group did not define hypotension, arrhythmia, altered mental status and slurred speech, but used the definitions used in the studies.

The working group defined one point as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference on a 10-point pain score and 10 mm on a 100 mm pain scale. Regarding postoperative opioid consumption, a difference of 10 mg was considered clinically relevant. For dichotomous variables, a difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant (RR <0.91 or >1.10; RD 0.10).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 26-1-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1,199 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic review or RCT

- Published ≥ 2000

- Patients ≥ 18 years

- Conform either of the PICOs

A total of 19 systematic reviews were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 17 systematic reviews were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods). Subsequently, RCTs were screened that were published after the search date of the included systematic reviews. Therefore, 11 recently published RCTs were included in addition to the systematic reviews.

Results

Two systematic reviews and 11 recently published RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature.

For PICO 1, lidocaine vs. standard care, the Cochrane review by Weibel (2018), and 11 recent RCTs were included. Weibel (2018) included 66 RCTs comparing lidocaine to standard care.

For PICO 2, lidocaine vs. epidural analgesia, the Cochrane review by Weibel (2018) was included again, and 3 additional RCTs. Weibel (2018) included 2 RCTs comparing lidocaine to epidural analgesia.

Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Caille G, Lelorier J, Latour Y, Besner JG. GLC determination of lidocaine in human plasma J Pharm Sci. 1977 Oct;66(10):1383-5.

- Dunn LK, Durieux ME. Perioperative Use of Intravenous Lidocaine. Anesthesiology. 2017 Apr;126(4):729-737. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001527. PMID: 28114177.

- Foo I, Macfarlane AJR, Srivastava D, Bhaskar A, Barker H, Knaggs R, Eipe N, Smith AF. The use of intravenous lidocaine for postoperative pain and recovery: international consensus statement on efficacy and safety. Anaesthesia. 2021 Feb;76(2):238-250.

- Foo I, Macfarlane AJR, Srivastava D, Bhaskar A, Barker H, Knaggs R, Eipe N, Smith AF. The use of intravenous lidocaine for postoperative pain and recovery: international consensus statement on efficacy and safety Anaesthesia. 2021 Feb;76(2):238-250. doi: 10.1111/anae.15270.

- Ghimire A, Subedi A, Bhattarai B, Sah BP. The effect of intraoperative lidocaine infusion on opioid consumption and pain after totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernioplasty: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020 Jun 3;20(1):137.

- Ho MLJ, Kerr SJ, Stevens J. Intravenous lidocaine infusions for 48 hours in open colorectal surgery: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2018 Feb;71(1):57-65.

- Kendall MC, McCarthy RJ, Panaro S, Goodwin E, Bialek JM, Nader A, De Oliveira GS Jr. The Effect of Intraoperative Systemic Lidocaine on Postoperative Persistent Pain Using Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials Criteria Assessment Following Breast Cancer Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pain Pract. 2018 Mar;18(3):350-359.

- Kutay Yazici K, Kaya M, Aksu B, Ünver S. The Effect of Perioperative Lidocaine Infusion on Postoperative Pain and Postsurgical Recovery Parameters in Gynecologic Cancer Surgery. Clin J Pain. 2021 Feb 1;37(2):126-132. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000900. PMID: 33229930.

- Miller M. Safety of postoperative lidocaine infusions on general care wards without continuous cardiac monitoring in an established enhanced recovery program. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2022;0:12.

- Peng X, Zhao Y, Xiao Y, Zhan L, Wang H. Effect of intravenous lidocaine on short-term pain after hysteroscopy: a randomized clinical trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021 Jul-Aug;71(4):352-357. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.015. Epub 2021 Feb 6. PMID: 34229861; PMCID: PMC9373697.

- Pöpping DM, Zahn PK, Van Aken HK, Dasch B, Boche R, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Effectiveness and safety of postoperative pain management: a survey of 18 925 consecutive patients between 1998 and 2006 (2nd revision): a database analysis of prospectively raised data. Br J Anaesth. 2008 Dec;101(6):832-40. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen300. Epub 2008 Oct 22. PMID: 18945716.

- Lv X, Li X, Guo K, Li T, Yang Y, Lu W, Wang S, Liu S. Effects of Systemic Lidocaine on Postoperative Recovery Quality and Immune Function in Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Radical Gastrectomy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 May 3;15:1861-1872. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S299486. PMID: 33976537; PMCID: PMC8106403.

- Rekatsina M, Theodosopoulou P, Staikou C. Effects of Intravenous Dexmedetomidine Versus Lidocaine on Postoperative Pain, Analgesic Consumption and Functional Recovery After Abdominal Gynecological Surgery: A Randomized Placebo-controlled Double Blind Study. Pain Physician. 2021 Nov;24(7):E997-E1006. PMID: 34704710.

- Sherif AA, Elsersy HE. The impact of dexmedetomidine or xylocaine continuous infusion on opioid consumption and recovery after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017 Dec;83(12):1274-1282. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.17.11855-9. Epub 2017 Jun 12. PMID: 28607333.

- Song X, Sun Y, Zhang X, Li T, Yang B. Effect of perioperative intravenous lidocaine infusion on postoperative recovery following laparoscopic Cholecystectomy-A randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2017 Sep;45:8-13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.07.042. Epub 2017 Jul 10. PMID: 28705592.

- Wang Q, Ding X, Huai D, Zhao W, Wang J, Xie C. Effect of Intravenous Lidocaine Infusion on Postoperative Early Recovery Quality in Upper Airway Surgery. Laryngoscope. 2021 Jan;131(1):E63-E69. doi: 10.1002/lary.28594. Epub 2020 Mar 2. PMID: 32119135.

- Weibel S, Jelting Y, Pace NL, Helf A, Eberhart LH, Hahnenkamp K, Hollmann MW, Poepping DM, Schnabel A, Kranke P. Continuous intravenous perioperative lidocaine infusion for postoperative pain and recovery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jun 4;6(6):CD009642. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009642.pub3. PMID: 29864216; PMCID: PMC6513586.

- Xu S, Wang S, Hu S, Ju X, Li Q, Li Y. Effects of lidocaine, dexmedetomidine, and their combination infusion on postoperative nausea and vomiting following laparoscopic hysterectomy: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021 Aug 4;21(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12871-021-01420-8. PMID: 34348668; PMCID: PMC8336323.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Ghimire, 2020 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Computer-based randomization |

Probably no;

Reason: Not described |

Probably yes

Reason: Patients, data collectors and outcome assessors were blinded. Other personnel not reported. |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

|

|

Herzog, 2020 |

Probably no;

Reason: randomization using number sequence by the hospital pharmacy |

Probably no;

Reason: numbered containers by the hospital pharmacy, no details |

Definitely tes

Reason: investigators, patients, nurses, surgeons and the statistician were blinded |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concern |

|

Kendall, 2018 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Computer-based randomization |

Definitely yes;

Reason: sealed opaque envelopes were used |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All patients and other personnel were blinded |

Probably no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was frequent in both groups. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concern |

|

Kim, 2017 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computer-generated random number sequence |

Definitely yes;

Reason: sealed opaque envelopes were used |

Probably yes;

Reason: surgeons, patients, and outcome assessors were blinded. Statisticians not reported |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

|

|

Lv, 2021 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: computer-generated random number sequence |

Definitely yes;

Reason: sealed opaque envelopes were used |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All patients and other personnel were blinded |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was 0 in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW

|

|

Peng, 2021 |

Probably yes;

Reason: random number table method performed by an Independent Anesthetist |

Probably no;