Intrathoracaal borstwandblokken

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de rol van borstwandblokken (paravertebraal block) ten opzichte van epidurale pijnstilling bij patiënten die een intrathoracale chirurgische procedure ondergaan?

Aanbeveling

Geef een lichte voorkeur aan een continue paravertebrale blok boven een epiduraal voor thoracotomieën en VATS.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is een systematische literatuuranalyse uitgevoerd naar effecten van een continue paravertebraal blok en epidurale pijnstilling op postoperatieve pijn, postoperatieve opioïdengebruik en adverse events. Er werd literatuur gevonden voor de vergelijking bij twee typen chirurgie: thoracotomie en VATS. Postoperatieve pijn op 0, 6, 12, 24 en 48 uur na de ingreep was de cruciale uitkomstmaat, en chronische pijn, gebruik van opioïden en complicaties waren belangrijke uitkomstmaten voor klinische besluitvorming. Alle studies hadden methodologische beperkingen, waardoor er mogelijk risico is op vertekening van de studieresultaten (risk of bias) bij de subjectieve uitkomstmaten.

1. Thoracotomie

Voor postoperatieve pijn werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden voor geen van de tijdstippen (lage GRADE).

Voor pijn gemeten op 6 uur na de ingreep komt postoperatieve pijn mogelijk in dezelfde mate voor, en voor pijn gemeten op 24 uur na de ingreep was de evidentie van te lage bewijskracht (zeer lage GRADE) om een conclusie te trekken.

Het bewijs op het gebied van chronische pijn suggereert een vergelijkbaar effect op 3 en 12 maanden.

Wat betreft de uitkomstmaat gebruik van opioïden was de evidentie van te lage bewijskracht (zeer lage GRADE) om een conclusie te trekken.

Het bewijs voor incidentie van adverse event hypotensie was redelijk en suggereert een klinisch relevant verschil van een lagere incidentie in het voordeel van paravertebraal blok.

De overall bewijskracht, namelijk de laagste bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat, komt uit op zeer laag.

2. VATS

Voor postoperatieve pijn op 0-1 uur tijdens rust, werd een mogelijk klinisch relevant verschil gevonden in het voordeel van epidurale pijnstelling (lage GRADE). Voor de andere tijdstippen werd geen klinisch relevant verschil gevonden (lage GRADE) of was de evidentie van de bewijskracht te laag om een conclusie te kunnen trekken (zeer lage GRADE).

Op het gebied van chronische pijn was er voor deze vergelijking geen onderzoek. Wat betreft de uitkomstmaat gebruik van opioïden was de evidentie van te lage bewijskracht (zeer lage GRADE) om een conclusie te trekken.

Het bewijs voor de complicatie hypotensie was laag, er werd mogelijk een klinisch relevant verschil gevonden van een lagere incidentie in het voordeel van paravertebraal blok.

De overall bewijskracht, namelijk de laagste bewijskracht van de cruciale uitkomstmaat, komt uit op zeer laag.

Samenvattend is er een minimaal beter analgetisch effect van een epiduraal vergeleken met een continue paravertebraal blok gemeten middels postoperatieve pijnscores en opioïdengebruik, maar met meer kans op hypotensie.

Over een eventueel verschil in effect op chronische pijn van continue paravertebrale en epidurale analgesie bij VATS en thoracotomie kan geen uitspraak worden gedaan, dit is een kennishiaat.

Er is een zwakke bewijskracht qua analgetisch effect (ten voordeel van epiduraal) vergeleken met de iets sterkere bewijskracht qua complicaties (hypotensie: ten voordeel van continue paravertebraal).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Als een continue paravertebraal blok ook intra-operatief bv. door de thoraxchirurg zelf zou ingebracht kunnen worden, dan wordt dit door patiënten als minder belastend ervaren. Bij de afweging tussen wellicht een iets beter analgetisch effect van een epiduraal blok en minder complicaties bij een continue paravertebraal blok zouden naast eventuele comorbiditeit van de patiënt, diens waarden en voorkeuren meegenomen kunnen worden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Vaak wordt dezelfde locoregionale set gebruikt voor een continue paravertebraal blok als voor een epiduraal blok; en worden beiden postoperatief vervolgd door een APS-team. Daardoor zou er geen verschil in kosten zijn tussen beide technieken

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie is niet expliciet onderzocht. Maar epiduraal en continue paravertebraal blok kunnen allebei als een standaard locoregionale techniek in de anesthesiologie beschouwd worden. Er is echter wel meer ervaring (exposure) onder anesthesiologen met epiduraal dan een continue paravertebraal. Er is geen vergelijkende studie naar de leercurve tussen een epiduraal en paravertebraal, maar van het paravertebraal blok is bekend dat deze technisch moeilijker uitvoerbaar is (Coveney, 1998). Specifieke complicaties voor epidurale analgesie zijn het optreden van hypotensie (redelijk frequent) en ernstige neurologische schade(zelden). Continue paravertebraal heeft als belangrijkste complicatie een pneumothorax. Een paravertebraal valt onder intermediair bloedingen-risico versus epiduraal hoog-risico.

In het merendeel van de beschreven studies werd het continue paravertebraal blok ingebracht door de anesthesioloog (12 van de 20 studies). Met name in de meest recente studies gepubliceerd in de laatste 10 jaar werd dit echogeleid uitgevoerd. Mogelijk kan dit leiden tot effectievere pijnstilling (Patnaik 2018), hoewel dit niet expliciet is geëvalueerd in deze module.

Vaak kan een continue paravertebraal blok ook intra-operatief en zelf door de thoraxchirurg ingebracht worden. In 8 van de 20 beschreven studies werd het continue paravertebraal blok intra-operatief ingebracht door de operateur. Dit zou qua tijdsinvestering voor inbrengen van het blok en belasting voor de patiënt (slapend versus wakker) een duidelijk voordeel van een continue paravertebraal blok zijn.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De overall bewijskracht, namelijk de laagste bewijskracht op pijnscores en opioïdengebruik, komt uit op zeer laag. Voor thoracotomieën en VATS geeft een continue paravertebraal blok dezelfde mate van pijnstilling in vergelijking met een epiduraal blok. Gezien er minder hypotensie (en kans op ernstige neurologische complicaties) van een continue paravertebraal te verwachten zijn, bestaat er een lichte voorkeur voor een continue paravertebraal blok boven een epiduraal. Ondanks dat beide technieken tot het standaard arsenaal van de anesthesioloog behoren, is er meer ervaring met epidurale pijnbestrijding. Aandacht voor scholing is nodig.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Van oudsher werd epidurale pijnstilling gebruikt bij patiënten die een intrathoracale chirurgische procedure ondergaan. Recenter worden meer loco-regionale borstwandblokken gebruikt, zoals erector spinae (ESP) blok, intercostaal (IN) blok, en met name paravertebraal blok (PVB). Deze laatste staat ook als lichte voorkeur in vorige richtlijn boven epiduraal en wordt in Nederland samen met de epiduraal waarschijnlijk het vaakst gebruikt in deze categorie operaties. Vandaar dat voor deze module de focus ligt op de vergelijking tussen een epiduraal en een continue paravertebraal blok.

De vraag die de werkgroep heeft voor deze module is als volgt: Heeft een continue paravertebraal blok de voorkeur boven epiduraal bij intrathoracale chirurgie?

Conclusies

Conclusions

- Postoperative pain

|

Low GRADE |

Use of continuous PVB may result in little to no difference in postoperative pain at 2-6, 24, and 48 hours at rest and coughing/ physiotherapy when compared with the use of a TEB in adults undergoing thoracotomy.

Source: Yeung, 2016; Li, 2021 |

- Chronic postoperative pain

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of continuous PVB compared with the use of TEB for chronic postoperative pain at 6 months in adults undergoing thoracotomy.

Source: Khoronenko, 2018; Li, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Use of continuous PVB may result in little to no difference in chronic postoperative pain at 3 and 12 months when compared with the use of a TEB in adults undergoing thoracotomy.

Sources: Li, 2021 |

- Postoperative opioid consumption

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of continuous PVB compared with the use of TEB for postoperative opioid consumption in adults undergoing thoracotomy.

Source: Huang, 2020 |

- Adverse events

Bleeding

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found.

Source: - |

Hypotension

|

Moderate GRADE |

Use of continuous PVB likely results in a lower incidence of hypotension in adults undergoing thoracotomy when compared with the use of TEB.

Source: Yeung, 2016 |

Surgery type 2: Video-Assisted Thoractomy (VAT)

1. Postoperative pain

Okajima (2015) and Yeap (2021) provided absolute data for postoperative pain comparing PVB with TEB. Results are presented in table 4. Yeap (2021) made a distinction between PVB catheter (PVB-A) and single-injection PVB (PVB-B). in the study of Okajima (2015) four blocks of PVB and one catheter insertion were performed (results presented under PVB-B).

1.1. Postoperative pain at 0-1h

1.1.1. At rest

Okajima (2015) reported a median difference in pain scores at rest between PVB (n=36) and TEB (n=33) of 2.5 in favour of PVB. This difference was considered clinically relevant.

Yeap (2021) reported a median differences in pain scores at rest between PVB catheter (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 1 in favour of PVB and no difference in pain scores at rest between single-injection PVB (n=40) and TEB (n=40). The difference between PVB catheter and TEB was considered clinically relevant.

1.1.2. At mobilization

Yeap (2021) reported a median differences in pain scores at mobilization between PVB catheter (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 0.5 in favour of PVB and no differences in pain scores at mobilization between single-injection PVB (n=40) and TEB (n=40). The differences were not considered clinically relevant.

1.2. Postoperative pain at 6h

1.2.1. At rest

Okajima (2015) reported no difference in pain scores at rest between PVB (n=36) and TEB (n=33).

1.3. Postoperative pain at 12h

1.3.1. At rest

Okajima (2015) reported no difference in pain scores at rest between PVB (n=36) and TEB (n=33).

1.4. Postoperative pain at 24h

1.4.1. At rest

Okajima (2015) reported no difference in pain scores at rest between PVB (n=36) and TEB (n=33).

Yeap (2021) reported a median difference of pain scores at rest between PVB catheter (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 1 in favour of TEB and a median differences of pain scores at rest between single-injection PVB (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 0.5 in favour of TEB. The difference between PVB catheter and TEB was considered clinically relevant.

1.4.2. At mobilization

Yeap (2021) reported a median difference of pain scores at mobilization between PVB catheter (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 0.5 in favour of TEB and a median differences of pain scores at rest between single-injection PVB (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 1 in favour of TEB. The difference between single-injection PVB and TEB was considered clinically relevant.

1.5. Postoperative pain at 48h

1.5.1. At rest

Okajima (2015) reported no difference in pain scores at rest between PVB (n=36) and TEB (n=33).

Yeap (2021) reported a median difference of pain scores at rest between PVB catheter (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 1 in favour of TEB and a median difference of pain scores at rest between single-injection PVB (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 2 in favour of TEB. These differences were considered clinically relevant.

1.5.2. At mobilization

Yeap (2021) reported a median differences of pain scores at mobilization between PVB catheter (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 1 in favour of TEB and a median differences of pain scores at rest between single-injection PVB (n=40) and TEB (n=40) of 2 in favour of TEB. These differences were considered clinically relevant.

Table 4. Postoperative pain scores in median (IQR).

|

Study |

Pain |

PVB-A |

n |

PVB-B

|

n |

TEB |

n |

Median difference |

|

|

PVB-A vs. TEB |

PVB-B vs. TEB |

||||||||

|

0-1h |

|||||||||

|

Okajima (2015) |

VRS (0-10) at rest |

- |

- |

1,5 (0-6) |

36 |

4 (0-7) |

33 |

- |

-2,5 in favour of PVB, clinically relevant |

|

Yeap (2021) |

VAS (0-10) at rest |

5.0 (3.0-8.0) |

40 |

6.0 (3.5-8.0) |

40 |

6.0 (3.5-8.0) |

40 |

-1 in favour of PVB, clinically relevant |

0, none, no |

|

|

VAS (0-10) at mobilization |

6.5 (4.0-9.0) |

40 |

7.0 (5.0-9.0) |

40 |

7.0 (5.0-9.0) |

40 |

-0,5 in favour of PVB, not clinically relevant |

0, none, no |

|

6h |

|||||||||

|

Okajima (2015) |

VRS (0-10) at rest |

- |

- |

1 (0-3) |

36 |

1 (0-3,25) |

33 |

- |

0, none, no |

|

12h |

|||||||||

|

Okajima (2015) |

VRS (0-10) at rest |

- |

- |

1 (0-3) |

36 |

1 (0-1,25) |

33 |

- |

0, none, no |

|

24h |

|||||||||

|

Okajima (2015) |

VRS (0-10) at rest |

- |

- |

1 ( 0-3) |

36 |

1 (0-2) |

33 |

- |

0, none, no |

|

Yeap (2021) |

VAS (0-10) at rest |

4.0 (3.0-5.5) |

40 |

4.5 (2.5-6.0) |

40 |

3.0 (1.0-5.0) |

40 |

1 in favour of TEB, clinically relevant |

0,5 In favour of TEB, not clinically relevant |

|

|

VAS (0-10) at mobilization |

6.5 (5.0-8.0) |

40 |

7.0 (5.0-8.0) |

40 |

6.0 (2.0-7.0) |

40 |

0,5 in favour of TEB, not clinically relevant |

1 In favour of TEB, clinically relevant |

|

POD2/48h |

|||||||||

|

Okajima (2015) |

VRS (0-10) at rest |

- |

- |

1 (0-3) |

36 |

1 (0-3,5) |

33 |

- |

0, none, no |

|

Yeap (2021) |

VAS (0-10) at rest |

3.0 (1.0-5.0) |

40 |

4.0 (2.0-6.0) |

40 |

2.0 (1.0-4.0) |

40 |

1 in favour of TEB, clinically relevant |

2 In favour of TEB, clinically relevant |

|

|

VAS (0-10) at mobilization |

5.0 (3.0-7.0) |

40 |

6.0 (3.0-8.0) |

40 |

4.0 (2.0-6.0) |

40 |

1 in favour of TEB, clinically relevant |

2 In favour of TEB, clinically relevant |

PVB-A = paravertebral block catheter; PVB-B = single-injection paravertebral block TEB = thoracic epidural blockade.

Unfortunately, the other RCTs reported postoperative pain scores at the different timepoints in graphs, from which the absolute data could not be extracted. Ding (2018) measured postoperative pain using a verbal rating score (VRS; scale of 0–10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable) assessed at 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after surgery at rest and after coughing. The authors report no significant difference in VRS during coughing among the two groups at 2 hours after surgery. At 6 and 12 hours after surgery, patients in the TEB group had a lower VRS during coughing as compared to the PVB group. There were no significant differences in VRS during coughing among the three groups at 24 and 48 hours after surgery.

Kosiński (2016) measured postoperative pain according to VAS at 1, 24 and 48 hours after the procedures. Both static (at rest) and dynamic assessments (on cough) were performed. The authors report significant differences in the measurements at 24 hours after surgery — both at rest and on coughing (P = 0.01 and P = 0.023, respectively); and in static pain at 48 hours after surgery (P = 0.026), in favour PVB.

Lai (2021) measured VAS at rest and on coughing at PACU, 6, 24 and 48 hours postoperatively. The authors report significant differences in pain at 24 hours at rest and on coughing (P = 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively), in favour of TEB, and no significant differences between the two groups at other time points.

Because only the statistical significance of the results was presented and no absolute values were reported, no interpretation can be given for the clinical relevance of these results.

2. Chronic postoperative pain

Not reported.

3. Postoperative opioid consumption

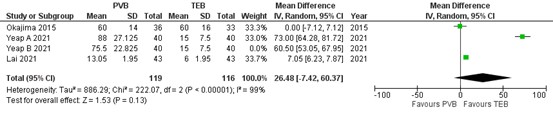

Three RCTs reported on postoperative opioid consumption. Results of the meta-analysis is presented in figure 5. As mentioned earlier, Yeap (2021) made a distinction between PVB catheter (A) and single-injection PVB (B). Because Okajima (2015) and Lai (2021) reported on PVB catheter, only the group A of Yeap (2021) was included in the meta-analysis. The mean difference (MD) of opioid consumption between PVB (n=119) and TEB (n=116) was 26.48 (95% CI -7.42 to 60.37) in favour of TEB. This difference was clinically relevant.

Figure 5. Postoperative opioid consumption.

Opioids were converted into equianalgesic doses of i.v. morphine for analysis (i.v. morphine 10 mg =i.v. fentanyl 100 μg = i.v. sufentanil 10 μg). Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = epidural anesthesia

Ding (2018) and Kosiński (2016) reported postoperative opioid consumption in graphs from which the absolute date could not be extracted. Ding (2018) compared the total dose of sufentanil used during the 48-h postoperative period. Compared to the PVB group (n= 36), patients in the TEA group (n=32) received lower doses of sufentanil in the 48 h after surgery (p=0.005). Kosiński (2016) reported the emergency PCA-administered morphine doses (mg h-1) per day in the follow-up time of 72 hours. The comparative analysis of both groups (PVB, n=26; TEB, n=25) did not reveal any significant differences. The mean dose was 0.4 mg h-1 on day 0, 0.37 mg h-1 on day 1, 0.21 on day 2 and 0.14 mg h-1 on day 3. Because only the statistical significance and combined mean values of the comparative analyses were presented and no absolute values were reported, no interpretation can be given for the clinical relevance of these results.

4. Adverse events

4.1. Bleeding

Not reported.

4.2. Hypotension

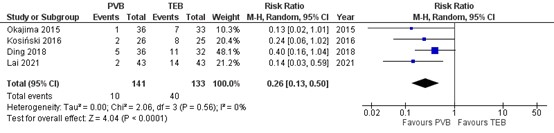

Four RCTs reported on the incidence of hypotension. Results are presented in figure 6. The number of patients with hypotension was higher in patients treated with TEB (40 of 133, 30%) compared to patients treated with PVB (10 of 141, 7.1%) (RR=0.26 95% CI 0.13 to 0.50). This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 6. Incidence of hypotension .

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = epidural anesthesia

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on randomized studies and therefore starts at high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 0-1 at rest and mobilization was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 6 and 12 hours at rest was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain 24 hours at rest was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain 24 hours at mobilization was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 48 hours at rest was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 48 hours at mobilization was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); conflicting results (inconsistency, -1); and limited numbers of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and limited number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

Conclusions

- Postoperative pain

|

Low GRADE |

Use of continuous PVB may result in less postoperative pain at 0-1 hours at rest, when compared with the use of a TEB in adults undergoing VATS.

Use of continuous PVB may result little to no difference in postoperative pain at 0-1 hours at mobilization, when compared with the use of a TEB in adults undergoing VATS.

Use of continuous PVB may result little to no difference in postoperative pain 6 and 12 hours at rest, when compared with the use of a TEB in adults undergoing VATS.

Source: Okajima, 2015; Yeap, 2021 |

|

Very Low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of continuous PVB compared with the use of TEB for postoperative pain at 24 and 48 hours at rest and at mobilization in adults undergoing VATS.

Source: Okajima, 2015; Yeap, 2021 |

- Chronic postoperative pain

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found.

Source: - |

- Postoperative opioid consumption

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the use of continuous PVB compared with the use of TEB for postoperative opioid consumption in adults undergoing VATS.

Source: Okajima, 2015; Yeap, 2021; Lai, 2021 |

- Adverse events

Bleeding

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found.

Source: - |

Hypotension

|

Low GRADE |

Use of continuous PVB may result in a lower incidence of hypotension in adults undergoing VATS when compared with the use of TEB.

Source: Okajima, 2015; Kosiński, 2016; Ding, 2018; Lai, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Main study characteristics of all included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are outlined in table 1. As shown in the table, studies included various surgical procedures, different thoracic wall block solutions and follow-up time.

Yeung (2016) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs to compare the two regional techniques of TEB and PVB in adults undergoing elective thoracotomy. The systematic review included 14 studies involving 798 participants. The review reports that the included studies demonstrated high heterogeneity in insertion and use of both regional techniques. In addition, the included studies had a moderate to high potential for bias, lacking details of randomisation, group allocation concealment or arrangements to blind participants or outcome assessors.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

|

Author, year |

N (I/C) |

Intervention |

Control |

Follow-up |

||

|

Method of insertion |

Method of use |

Method of insertion |

Method of use |

|||

|

|

Continuous PVB |

|

TEB |

|

|

|

From Yeung, 2016: |

||||||

|

Bimston, 1999

|

30/20 |

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

18 ml 0.5% bupivacaine Bolus followed by infusion of 0.1% bupivacaine with 10 μg/ml fentanyl, 10 - 15 ml/ hr. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Uncertain whether catheter was used during operation.

|

48h |

|

Casati, 2006

|

21/21 |

Percutaneously by landmark techniquebefore induction of GA. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

5 ml bolus of 0.75% ropivacaine. |

48h |

|

De Cosmo, 2002

|

25/25 |

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

Used at the end of operation only.

|

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

5 ml bolus of 0.2% ropivacaine and sufentanil 10 Zg given as bolus. Catheter used during operation if required. |

48h |

|

Grider, 2012

|

50/25 |

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

48h |

|

Gulbahar, 2020 |

25/19 |

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

48h |

|

Ibrahim, 2009

|

25/25 |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

15 - 20 ml 0.5% ropivacaine bolus followed by 0.375% ropivacaine 0.1 ml/kg/hr infusion. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

15 - 20 ml 0.5% ropivacaine bolus followed by 0.375% ropivacaine 0.1 ml/kg/hr infusion. |

48h |

|

Kobayashi, 2013 |

35/35 |

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

48h |

|

Matthews, 1989 |

10/10 |

Percutaneously by landmark at the end of procedure. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

48h |

|

Messina, 2009 |

12/12 |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

Used at the end of operation only. |

48h |

|

Pintaric, 2011 |

16/16 |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

0.5% levopubivacaine with 30 μg/kg morphine. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

0.25% levopubivacaine with 30 μg/kg morphine. |

48h |

|

Richardson, 1999 |

46/54 |

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

20 ml bolus of 0.5% bupivacaine, followed by infusion at 0.1 ml/kg/hr. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

10 - 15 ml bolus of 0.25% bupivacaine.

|

48h |

|

Huang, 2020

|

45 (IA)/32 (IB)/39 (C) |

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

Group A: interplanar approach in an oblique axial transverse section.

A dose of 1 mg kg-1 of 0.33% of ropivacaine + a dose of 0.7 mg kg-1 of 0.33% ropivacaine added every 4 h during the operation.

Group B: interplanar approach in sagittal parasagittal section.

A dose of 1 mg kg-1 of 0.33% of ropivacaine + a dose of 0.7 mg kg-1 of 0.33% ropivacaine added every 4 h during the operation. |

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

Injection of 0.25% of ropivacaine (3 ml) via the catheter. Another 3–5 ml was added every 5 min during the operation + 0.25% of ropivacaine 3–5 ml every 2 h during the operation. |

48h |

|

Khoronenko, 2018

|

100/100

|

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

sevoflurane (0.8–1 MAC), fentanyl (0.05–0.1 mg i.v. every 15–30 minutes when the SBP increased by more than 15% from the baseline value or was >140 mmHg). |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

sevoflurane (0.8–1 MAC), fentanyl (0.05–0.1 mg i.v. every 15–30 minutes when the SBP increased by more than 15% from the baseline value or was >140 mmHg). |

6 months |

|

Li, 2021 |

42/41 |

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

single-shot 20 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine combined with 1 µg/kg dexmedetomidine. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

continuous infusion of sufentanil (0.2 μg/mL) and ropivacaine 0.06% at 5–10 mL/h during the operation. |

12 months |

|

Tamura, 2017 |

36/36

|

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon. |

20 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine as a bolus, followed by a 300-mL of continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

5 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine as a bolus, followed by a 300-mL continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h. |

42h |

|

2) VATS |

|

|

Continuous PVB |

|

TEB |

|

|

Ding, 2018 |

36/32

|

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

single-dose 0.5% ropivacaine before the operation |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

0.5% ropivacaine and a single dose of epidural morphine (0.03 mg/kg) after extubating |

48hr |

|

Kosiński, 2016 |

26/25

|

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

continuous infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

continuous infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine |

72h |

|

Lai, 2021 |

43/43

|

Inserted under direct vision by surgeon (upon completion of surgery) |

initial bolus of 0.5% ropivacaine 0.1 mL/kg and then 0.1 mL/kg/h infusion for 48 h postoperatively. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

ropivacaine 0.15% with 6 mcg/mL of hydromorphone and was administered via a pump starting at 2 mL/h for 48 h postoperatively. |

72h |

|

Okajima, 2015 |

36/33 |

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

three single blocks with 5 ml of 0.5 % ropivacaine + 15 ml of 0.5 % ropivacaine for catheter insertion + continuous postoperative infusion (0.1 % ropivacaine plus fentanyl at 0.4 mg/day) for 36 h. |

Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA. |

bolus dose (5–7 ml) of 0.25–0.375 % ropivacaine + continuous postoperative infusion (0.1 % ropivacaine plus fentanyl at 0.4 mg/day) for 36 h. |

POD2 |

|

Yeap, 2021 |

40 (IA)/40 (IB)/40 (C) |

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

Group A: Ultrasound-guided PVB catheter.

Ropivacaine, 0.2%, was delivered postoperatively at a rate of 10 mL/h by infusion pump.

Group B: ultrasound-guided single-injection PVB

30 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine. |

Percutaneously, ultrasound-guided, before induction of GA. |

epidural mixture of 0.125% bupivacaine and 0.05 mg/mL of hydromorphone (starting at the end of the surgery). |

6 months |

PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = thoracic epidural blockade; h = hours.

Surgery type 1: Thoracotomy

Results

1. Postoperative pain

1.1. Postoperative pain at 2 to 6 hours

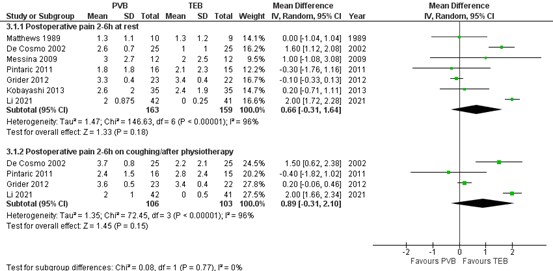

The systematic review by Yeung (2016) reported pain scores at 2 to 6 hours at rest and on coughing/ after physiotherapy for six RCTs. The additional RCT (Li, 2021) reported on postoperative pain scores at 6 hours which was added to the results of Yeung (2016) and on which a meta-analysis was performed. The results are presented in figure 1.

1.1.1. At rest

The mean difference (MD) of pain scores at rest between PVB (n=163) and TEB (n=159) was 0.66 (95% CI -0.31 to 1.64) in favour of TEB. This difference is not clinically relevant.

1.1.2. On coughing/ after physiotherapy

The mean difference (MD) of pain scores at rest between PVB (n=106) and TEB (n=103) was 0.89 (95% CI -0.31 to 2.10) in favour of TEB. This difference is not clinically relevant.

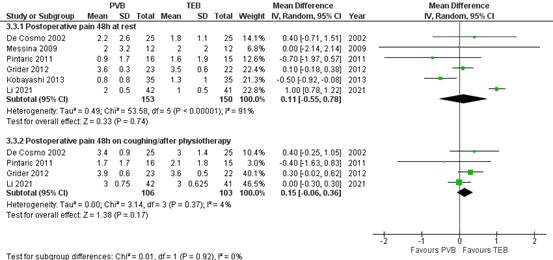

Figure 1. Postoperative pain at 2-6h at rest and on coughing/after physiotherapy.

Pain 2-6 hours postoperatively assessed by a 10-point VAS scale; random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = thoracic epidural blockade

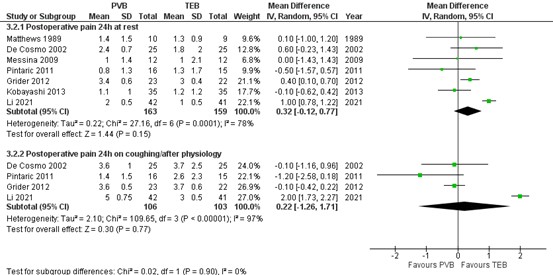

1.2. Postoperative pain at 24 hours

Pain scores at 24 hours at rest and on coughing/ after physiotherapy were reported by Yeung (2016; including 6 RCTs) and Li (2021) on which a meta-analysis could be performed. The results are presented in figure 2.

1.1.1. At rest

The mean difference (MD) of pain scores at rest between PVB (n=163) and TEB (n=159) was 0.32 (95% CI -0.12 to 0.77) in favour of TEB. This difference is not clinically relevant.

1.1.2. On coughing/ after physiotherapy

The mean difference (MD) of pain scores at rest between PVB (n=106) and TEB (n=103) was 0.22 (95% CI -1.26 to 1.71) in favour of TEB. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Postoperative pain at 24 at rest and on coughing/after physiotherapy

Pain hours postoperatively assessed by a 10-point VAS scale; random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = thoracic epidural blockade

1.3. Postoperative pain at 48 hours

Pain scores at 48 hours at rest and on coughing/ after physiotherapy were reported by Yeung (2016; including 5 RCTs) and Li (2021) on which a meta-analysis could be performed. The results are presented in figure 3.

1.3.1. At rest

The mean difference (MD) of pain scores at rest between PVB (n=153) and TEB (n=150) was 0.11 (95% CI -0.55 to 0.78) in favour of TEB. This difference is not clinically relevant.

1.3.2. On coughing/ after physiotherapy

The mean difference (MD) of pain scores at rest between PVB (n=106) and TEB (n=103) was 0.15 (95% CI -0.06 to 0.36) in favour of TEB. This difference is not clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Postoperative pain at 48h at rest and on coughing/after physiotherapy

Pain 48 hours postoperatively assessed by a 10-point VAS scale; random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = thoracic epidural blockade

Two other additional single RCTs reported postoperative pain scores at the different timepoints in graphs from which the absolute data could not be extracted. In Huang (2020) the numerical rating scale (NRS) scores at rest and during coughing at 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours after the surgery were recorded. The graphs with results on postoperative pain show that the NRS scores of the PVB-A and PBV-B groups are higher than TEB during both modalities and for all measured time-points. In addition, the authors reported that the rate of moderate pain at rest was similar, but the rate of moderate pain during coughing was the lowest in the TEB group. Furthermore, they reported that the TEB group had the least moderate pain during resting and coughing from 24 to 48 hours. Because no absolute values were reported, no interpretation can be given for the clinical relevance of these results.

Tamura (2017) recorded postoperative pain using a visual analog scale (VAS) while coughing, moving, and at rest 1, 2, 6, 12, 18, and 42 hours after a bolus injection of ropivacaine. The graphs with results on postoperative pain show that scores of the PVB group are higher than the TEB group for all modalities and each time-point. For all three modalities the pain for both PVB and TEB decrease over time. Also, for all three modalities, the difference between PVB and TEB for the earlier time-points is greater (about 80 mm for PVB versus 40/50 mm for TEB at 1 hour) than the difference at the later time-points (about 40/50 mm for PVB versus 20/30 for TEB at 42 hours). The authors additionally reported that all mean VAS scores in the TEB group were significantly lower than those in the PVB group. Because only the statistical significance of the results were presented and no absolute values were reported, no interpretation can be given for the clinical relevance of these results.

2. Chronic postoperative pain

Two RCTs reported on chronic pain. Khoronenko (2018) reported on the intensity of chronic pain on a VAS scale (0 for no pain and 100 mm for worst possible pain). Static and dynamic pain components were assessed 6 months after surgery. Li (2021) reported chronic pain scores at rest scored on a verbal rating scale (VRS; 0 for no pain, and 10 for the worst pain). Results of both studies are presented in table 2. Only for chronic pain at 3 months, Li (2021) reported a clinically different difference in favour of TEB.

Table 2. Chronic postoperative pain scores.

|

Study |

Pain |

PVB |

n |

TEB |

n |

Mean difference, 95% CI / median difference |

In favour of |

Clinically relevant? |

|

3 months |

||||||||

|

Li (2021) |

VRS (0-10) during rest, in median (range) |

1 (0-2) |

42 |

0 (0-1) |

41 |

1 |

TEB |

Yes |

|

6 months |

||||||||

|

Khoronenko (2018) |

VAS (0-100 mm) during rest in mean ± SD |

0.16 ± 0.39 |

100 |

0.10 ± 0.30 |

100 |

0.06, -0.04 to 0.16 |

TEB |

No |

|

|

VAS (0-100 mm) dynamic in mean ± SD |

0.59 ± 0.98 |

100 |

0.38 ± 0.79 |

100 |

0.21, -0.04 to 0.46

|

TEB |

No |

|

Li (2021) |

VRS (0-10) during rest, in median (range) |

0 (0-2) |

42 |

0 (0-1) |

41 |

0 |

None |

No |

|

12 months |

||||||||

|

Li (2021) |

VRS (0-10) during rest, in median (range) |

0 (0-1) |

42 |

C: 0 (0-0) |

41 |

0 |

None |

No |

PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = epidural anesthesia

3. Postoperative opioid consumption

The systematic review by Yeung (2016) did not report on postoperative opioid consumption. Of the additional included RCTs, only Huang (2020) reported on postoperative opioid consumption (in morphine milligram equivalents; MME). In the PVB group, they made a distinction between A) the interplanar approach in an oblique axial transverse section and B) the interplanar approach in sagittal parasagittal section. Results are presented in table 3. The mean difference in MME between PBV-A (n=45) and TEB (n=39) was 6.51 mg in favour of TEB (95% CI 3.77 to 9.25). The mean difference in MME between PBV-B (n=32) and TEB (n=39) was 6.74 mg in favour of TEB (95% CI 3.88 to 9.60). These differences were not clinically relevant.

Table 3. Postoperative opioid consumption in morphine milligram equivalents (MME) reported by Huang (2020).

|

PVB-A mean±SD |

n |

PVB-B mean±SD |

N |

TEB mean±SD |

n |

Mean difference [95% CI] |

|

|

PVB-A vs. TEB |

PVB-B vs. TEB |

||||||

|

8.75 ± 7.93 |

45 |

8.98 ± 7.09 |

32 |

2.24 ± 4.64 |

39 |

6.51 [3.77, 9.25]

|

6.74 [3.88, 9.60] |

PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = epidural anesthesia

4. Adverse events

4.1. Bleeding

Not reported.

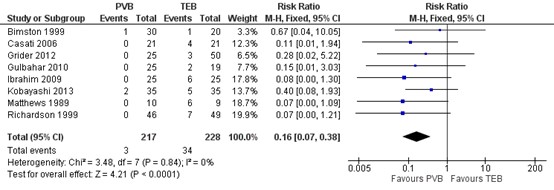

4.2. Hypotension

Eight RCTs included in Yeung (2016) reported on the incidence of hypertension. Results are presented in figure 4. The number of patients with hypotension was higher in patients treated with TEB (34 of 228, 14.9%) compared to patients treated with PVB (3 of 217, 0.9%) (RR=0.16 95% CI 0.07 to 0.38). This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 4. Incidence of hypotension.

Random effects model; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; Z: p-value of pooled effect. PVB = paravertebral block; TEB = epidural anesthesia

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcomes was based on randomized studies and therefore started at high.

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative pain at 2-6 hours, 24 hours and 48 hours at rest and coughing/ physiotherapy was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1) and conflicting results (inconsistency, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure chronic postoperative pain at 3 and 12 months was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -2). The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure chronic postoperative pain at 6 months was downgraded by 2 levels to low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and number of included patients (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure postoperative opioid consumption was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1); and because only one study with a limited number of included patients was available (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypotension was downgraded by 1 level to moderate because of study limitations (risk of bias, -1).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of thoracic wall blocks on postoperative pain, rescue medication (incl. postoperative opioid usage) and adverse events in adult patients undergoing an intrathoracic surgical procedure?

P (patients) Patients undergoing intrathoracic surgery

I (intervention) continuous paravertebral block (PVB)

C (control) thoracic epidural blockade (TEB)

O (outcome measure) postoperative pain

postoperative opioid consumption

chronic postoperative pain

adverse events

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered postoperative pain as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and chronic pain and postoperative opioid consumption and adverse events, as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measures as follows:

Postoperative pain (at rest and during mobilization/cough): Validated pain scale (Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) or Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) at post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) arrival, 6, 12, 24 and 48 hours post-surgery. Postoperative opioid consumption: defined as the total consumption in the first 24 hours after surgery (in Morphine Milligram Equivalent; MME). Chronic postoperative pain: pain > 3 months, in line with the international association study of pain (IASP). Adverse events: bleeding or hypotension.

The working group defined one point as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference on a 10-point pain scale and 10 mm on a 100 mm pain scale. Regarding postoperative opioid consumption, a difference of 10 mg was considered clinically relevant. For dichotomous variables, a difference of 10% was considered clinically relevant (RR ≤0.91 or ≥1.10; RD 0.10).

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 4-5-2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 435 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria:

- Systematic review of RCTs or RCT

- Thoracotomy or VATS

- Patients ≥18 years

- Conform PICO

Exclusion criteria:

- comparison of two variants of the same block

- comparisons with other blocks

- no original research

- n<20 per arm

A total of 68 studies (including 17 systematic reviews and 51 additional RCTs) were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 58 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 10 studies were included.

Results

One Cochrane systematic review (reporting on 11 RCTs) and nine additional single RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Literature was found for comparisons between paravertebral block (PVB) versus thoracic epidural blockade (TEB) for two surgery types: 1) thoracotomy (15 studies) and 2) video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) (5 studies). The summary of the literature and conclusions are divided into these surgery types. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Coveney E, Weltz CR, Greengrass R, Iglehart JD, Leight GS, Steele SM, Lyerly HK Use of paravertebral block anesthesia in the surgical management of breast cancer: experience in 156 cases Ann Surg. 1998 Apr;227(4):496-501.

- Ding W, Chen Y, Li D, Wang L, Liu H, Wang H, Zeng X. Investigation of single-dose thoracic paravertebral analgesia for postoperative pain control after thoracoscopic lobectomy - A randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2018 Sep;57:8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.07.006. Epub 2018 Jul 26. PMID: 30056127.

- Huang QW, Li JB, Huang Y, Zhang WQ, Lu ZW. A Comparison of Analgesia After a Thoracoscopic Lung Cancer Operation with a Sustained Epidural Block and a Sustained Paravertebral Block: A Randomized Controlled Study. Adv Ther. 2020 Sep;37(9):4000-4014.

- Khoronenko V, Baskakov D, Leone M, Malanova A, Ryabov A, Pikin O, Golovashchenko M. Influence of Regional Anesthesia on the Rate of Chronic Postthoracotomy Pain Syndrome in Lung Cancer Patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018 Aug 20;24(4):180-186.

- Kosi?ski S, Fry?lewicz E, Wi?koj? M, ?miel A, Zieli?ski M. Comparison of continuous epidural block and continuous paravertebral block in postoperative analgaesia after video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy: a randomised, non-inferiority trial. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2016;48(5):280-287. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2016.0059. PMID: 28000203.

- Lai J, Situ D, Xie M, Yu P, Wang J, Long H, Lai R. Continuous Paravertebral Analgesia versus Continuous Epidural Analgesia after Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Lobectomy for Lung Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021 Oct 20;27(5):297-303. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.20-00283. Epub 2021 Feb 16. PMID: 33597333; PMCID: PMC8560537.

- Li XL, Zhang J, Wan L, Wang J. Efficacy of Single-shot Thoracic Paravertebral Block Combined with Intravenous Analgesia Versus Continuous Thoracic Epidural Analgesia for Chronic Pain After Thoracotomy. Pain Physician. 2021 Sep;24(6):E753-E759. PMID: 34554693.

- Okajima H, Tanaka O, Ushio M, Higuchi Y, Nagai Y, Iijima K, Horikawa Y, Ijichi K. Ultrasound-guided continuous thoracic paravertebral block provides comparable analgesia and fewer episodes of hypotension than continuous epidural block after lung surgery. J Anesth. 2015 Jun;29(3):373-378. doi: 10.1007/s00540-014-1947-y. Epub 2014 Nov 15. PMID: 25398399.

- Patnaik R, Chhabra A, Subramaniam R, Arora MK, Goswami D, Srivastava A, Seenu V, Dhar A. Comparison of Paravertebral Block by Anatomic Landmark Technique to Ultrasound-Guided Paravertebral Block for Breast Surgery Anesthesia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018 May;43(4):385-390.

- Tamura T, Mori S, Mori A, Ando M, Yokota S, Shibata Y, Nishiwaki K. A randomized controlled trial comparing paravertebral block via the surgical field with thoracic epidural block using ropivacaine for post-thoracotomy pain relief. J Anesth. 2017 Apr;31(2):263-270.

- Yeap YL, Wolfe JW, Backfish-White KM, Young JV, Stewart J, Ceppa DP, Moser EAS, Birdas TJ. Randomized Prospective Study Evaluating Single-Injection Paravertebral Block, Paravertebral Catheter, and Thoracic Epidural Catheter for Postoperative Regional Analgesia After Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020 Jul;34(7):1870-1876.

- Yeung JH, Gates S, Naidu BV, Wilson MJ, Gao Smith F. Paravertebral block versus thoracic epidural for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 21;2(2):CD009121.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: Wat is de rol van borstwandblokken (paravertebral block, erector spinae plane block, Intercostal nerve block) ten opzichte van epidurale pijnstilling bij patiënten die een intrathoracale chirurgische procedure ondergaan?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) = PVB |

Comparison / control (C) = TEB

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

||

|

Method of insertion |

Method of use |

Method of insertion |

Method of use |

||||||

|

Yeung 2016

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing PVB with TEB in thoracotomy, including upper gastrointestinal surgery

Literature search up to [month/year]

A: Bimston 1999 B: Cesati 2006 C: De Cosmo, 2002 D: Grider, 2012 E: Gulbahar, 2020 F: Ibrahim, 2009 H: Kobayashi, 2013 I: Matthews, 1989 J: Messina 2009 M: Pintaric, 2011 N: Richardson, 1999

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: 2 hospitals, USA B: single centre, Italy C: single centre, Italy D: single centre, USA E: -, Turkey F: single centre, Egypt H: single centre, Japan I: -, UK J: single centre, Italy M: single centre, Slovenia N: single centre, UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: |

Inclusion/exclusion criteria SR: 1) Types of studies: We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We have excluded quasi-randomized trials, for example where allocation was determined by days of the week or hospital number. 2) Types of participants: We included all adults undergoing elective thoracotomy including for upper gastrointestinal surgery. 3) Types of interventions: We included continuous thoracic epidural infusions using local anaesthetics, opioids, and any adjuvant therapies. The comparator was continuous paravertebral blockade using local anaesthetics and adjuvant therapies.

11 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N (I/C) A: 30/20 B: 21/21 C: 25/25 D: 50/25 E: 25/19 F: 25/25 H: 35/35 I: 10/10 J: 12/12 M: 16/16 N: 46/54

Groups comparable at baseline? |

A: Inserted under direct vision by surgeon B: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA C: Inserted under direct vision by surgeons D: Inserted under direct vision by surgeon E: Inserted under direct vision by surgeon F: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA H: Inserted under direct vision by surgeon I: Percutaneously by landmark at the end of procedure J: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA M: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA N: Inserted by surgeon under direct vision

|

A: 18 ml 0.5% bupivacaine bolus followed by infusion of 0.1% bupivacaine with 10 `g/ml fentanyl, 10 - 15 ml/ hr B: Pre-op Injections by landmark technique before induction of GA 15 ml of 0.75% ropivacaine C: Used at the end of operation only D: Used at the end of the operation only E: Used at the end of operation only F: 15 - 20 ml 0.5% ropivacaine bolus followed by 0.375% ropivacaine 0.1 ml/kg/ hr infusion H: Used at the end of operation only I: Used at the end of operation only J: Used at the end of operation only M: 0.5% levopubivacaine with 30 `g/kg morphine, dose depends on height N: Pre-op Injections by landmark technique before induction of GA 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine

|

A: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA B: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA C: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA D: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA E: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA F: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA H: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA I: Percutaneously by landmark technique at the end of procedure J: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA M: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA N: Percutaneously by landmark technique before induction of GA

|

A: Uncertain whether catheter was used during operation B: 5 ml bolus of 0.75% ropivacaine C: 5 ml bolus of 0.2% ropivacaine and sufentanil 10 Zg given as bolus. Catheter used during operation if required D: Used at the end of operation E: Used at the end of operation F: 5 - 8 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine bolus followed by 0.375% ropivacaine 0.1 ml/kg.hr infusion H: Used at the end of operation I: Used at the end of operation J: Used at the end of operation M: 0.25% levopubivacaine with 30 `g/kg morphine, dose depends on height N: 10 - 15 ml bolus of 0.25% bupivacaine

|

End-point of follow-up: 48 hours

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) There was no study reporting high levels of missing data (less than 15% in all cases). However, we rated two studies at high risk of bias: Gulbahar 2010 excluded 6/50 participants (12%), but all from the epidural arm; Perttunen 1995 excluded 6/51 randomized participants (12%).

|

Postoperative pain Visual analogue scale scores (VAS) were used in all of the studies but the scales were different; a majority of studies used the 0 to 10 scale, but Kaiser 1998 used VAS in 0 to 4 categories (reported as mean and standard deviation (SD)), and two studies (Ibrahim 2009; Perttunen 1995) used VAS 0 to 5.

2-6h at rest SMD [95% CI]:

C: 1.82 [1.16, 2.49] D: -0.25 [-0.83, 0.34] H: 0.10 [-0.37, 0.57] I: 0.00 [-0.90, 0.90] J: 0.37 [-0.44, 1.18] M: -0.14 [-0.85, 0.56]

Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD 0.32, 95% CI -0.30 to 0.94

2-6h during coughing/ on movement SMD [95% CI]:

C: 0.93 [0.34, 1.52] D: 0.43 [-0.16, 1.02] M: -0.20 [-0.90, 0.51]

Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD 0.41, 95% CI -0.20 to 1.03

24h at rest SMD [95% CI]:

C: 0.39 [-0.17, 0.95] D: 0.77 [0.16, 1.37] H: -0.09 [-0.56, 0.38] I: 0.08 [-0.82, 0.98] J: 0.00 [-0.80, 0.80] M: -0.32 [-1.03, 0.39]

Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD 0.16, 95% CI -0.17 to 0.48

24h during coughing/ on movement SMD [95% CI]:

C: -0.05 [-0.61, 0.50] D: -0.18 [-0.76, 0.41] M: -0.61 [-1.33, 0.12]

Pooled effect (random effects model): SMD -0.23, 95% CI -0.58 to 0.12

Adverse events; hypotension RR [95% CI] A: 0.67 [0.04, 10.05] B: 0.11 [0.01, 1.94] D: 0.28 [0.02, 5.22] E: 0.15 [0.01, 3.03] F: 0.08 [0.00, 1.30] H: 0.40 [0.08, 1.93] I: 0.07 [0.00, 1.09] N: 0.07 [0.00, 1.21]

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.38

|

Aim: To compare the two regional techniques of TEB and PVB in adults undergoing elective thoracotomy with respect to: 1. analgesic efficacy; 2. the incidence of major complications (including mortality); 3. the incidence of minor complications; 4. length of hospital stay; 5. cost effectiveness.

|

Evidence table for intervention studies

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

PVB versus Epidural anesthesia - thoractomy |

|||||||

|

Huang, 2020 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single centre, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding: This research was supported by Fujian Natural Science Foundation, China (No. 2018J01206). The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors. CI: Qiao-Wen Huang, Jia-Bin Li, Ye Huang, Wen-Qing Zhang and Zhi-Wei Lu have nothing to disclose |

Inclusion criteria: elective unilateral thoracoscopic surgery for lung cancer (ASA II–III, aged less than 80 years old) from February 1, 2019 to October 31, 2019 in the Zhangzhou Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

Exclusion criteria: all patients that had a history of thoracic spine surgery; coagulopathy; a BMI of 28 kg m-2 or higher; a history of drug allergies; ASA C IV; and patients that refused to participate in the trial

Surgery: thoracoscopic surgery for lung cancer

N total at baseline: Intervention - T: 45 Intervention – P: 32 Control -E: 39

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I -T (n=50): 56.86 ± 10.31 I -P (n=50): 58.50 ± 9.61 C (n=48): 58.58 ± 9.68

Sex (M/F): I I -T (n=50): 31/19 I -P (n=50): 23/27 C (n=48): 30/18

Groups comparable at baseline? There was no significant difference in the general characteristics of the three groups of patients

|

ultrasound-guided continuous thoracic paravertebral block

2 subgroups: the interplanar approach in an oblique axial transverse section—T group;

0.33% of ropivacaine (AstraZeneca, imported drug registration no. H20140763, Lot NAZB) was injected at a dose of 1 mg kg-1

A dose of 0.7 mg kg-1 of 0.33% ropivacaine was added every 4 h during the operation

the interplanar approach in sagittal parasagittal section—P group

0.33% of ropivacaine (AstraZeneca, imported drug registration no. H20140763, Lot NAZB) was injected at a dose of 1 mg kg-1

A dose of 0.7 mg kg-1 of 0.33% ropivacaine was added every 4 h during the operation

|

continuous epidural analgesia (E-group)

injection of 0.25% of ropivacaine (3 ml) via the catheter. Another 3–5 ml was added every 5 min and the blocked segments by perceived less or lost sensation in response to cold and pinprick were tested until the blocked segments covered the surgical incision. The physician also recorded the plane stabilization time and the range of the blocking plane, and added 0.25% of ropivacaine 3–5 ml every 2 h during the operation. |

Length of follow-up: 48h

After randomization (n=150, 50 patients in each group)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention - T: 5 Reasons: haemorrhage (n=1); conversion of surgery approach (n=1); benign nodules (n=2); failure puncture (n=1)

Intervention – P: 18 Reasons: conversion of surgery approach (n=2); benign nodules (n=1); failure puncture (n=2); failure catheter placement (n=13)

Control -E: 11 Reasons: refuse (n=2); benign nodules (n=1); failure puncture (n=7);

Incomplete outcome data: n.a.

|

Postoperative pain numerical rating scale (NRS) scores at rest and during coughing at 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h after the surgery were recorded

Data per time-point reported in figure, not readable.

NRS ≥ 4 during 0–24 h post operation (n) I -T: 38 I -P: 26 C : 27

NRS ≥ 4 during 24–48 h post operation (n) I -T: 29 I -P: 23 C : 9

Opioid consumption

0–24 h opioids consumption (MME) I -T: 8.75 ± 7.93 I -P: 8.98 ± 7.09 C : 2.24 ± 4.64

24–48 h opioids consumption (MME) I -T: 10.28 ± 6.94 I -P: 9.38 ± 7.78 C : 1.60 ± 4.47

|

Study objective: to compare the challenge of puncture and catheterization and the effect of postoperative analgesia of ultrasound-guided continuous thoracic paravertebral block and the continuous epidural analgesia in patients receiving thoracoscopic surgery for lung cancer

Study conclusion: The continuous analgesia technique of paravertebral space catheterization cannot replace the continuous epidural analgesia in thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery as the latter technique is still considered to be the gold standard |

|

Khoronenko, 2018

|

Type of study: RCT*

Setting and country: single centre, France

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding: The study was only supported by departmental funds. CI: All authors have no conflict of interest. |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status from I to III

Exclusion criteria: general anesthesia within 7 days before study inclusion, administration of an experimental drug within 30 days before surgery, preoperative pain syndrome, or use of analgesics, acute unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction documented by laboratory findings within the past 6 weeks, heart rate (HR) <50 beats per minute (bpm), systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 100 mmHg, heart block, and preoperative vasopressor administration.

Surgery: thoracotomy for non-small-cell lung cancer

N total at baseline: I1: 100

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I1: 58 ± 9

Sex (m/f): I1: 77/23

Groups comparable at baseline? The groups were comparable regarding demographic features, blood loss, and type and duration of surgery

|

I1: PVB

Propofol (2 mg/kg), fentanyl (0.002 mg/kg), ketamine (25 mg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) were administered for induction. After endotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (0.8–1 MAC), fentanyl (0.05–0.1 mg IV every 15–30 minutes when the SBP increased by more than 15% from the baseline value or was >140 mmHg).

|

TEA

Propofol (2 mg/kg), fentanyl (0.002 mg/kg), ketamine (25 mg), and rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) were administered for induction. After endotracheal intubation, anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane (0.8–1 MAC), fentanyl (0.05–0.1 mg IV every 15–30 minutes when the SBP increased by more than 15% from the baseline value or was >140 mmHg).

|

Length of follow-up: 6 months

Loss-to-follow-up (total)*: Screened: 347 of whom 47 met exclusion criteria

Reasons: 17 patients suffered from an atrioventricular block I–II, 23 patients had a HR less than 50 bpm, and seven patients had preoperative hypotension with SBP less than 100 mmH.

Incomplete outcome data: Not reported

|

Chronic pain Horizontal VAS: 0 = no pain and 100 mm = worst possible pain. Static and dynamic pain components were assessed 7 days, 1 month, and 6 months after surgery

6 months – static (means ± standard deviation) I1: 0.16 ± 0.39 C: 0.10 ± 0.30

6 months – dynamic (means ± standard deviation) I1: 0.59 ± 0.98 C: 0.38 ± 0.79

|

*note that this is a study with 3 comparisons: PVB, INB and TEA

Stjudy objective: to assess whether the type of regional anesthesia influenced the incidence of chronic postthoracotomy pain syndrome (CPTPS).

Study conclusion: Patients who were administered TEA had less incidence and reduced intensity of CPTPS when compared with INB. Six months after surgery, the incidences of CPTPS were 23%, 34%, and 40% in the TEA, PVB, and INB groups, respectively. We did not find differences in CPTPS frequency and intensity between PVB and other groups. A pain syndrome that persists more than 1 month after surgery should be considered a predictor of pain syndrome chronicity.

|

|

Li, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single-centre, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding: There was no external funding in the preparation of this manuscript. CI: h author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial association (i.e., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted manuscript. |

Inclusion criteria: patients scheduled for elective thoracotomy

Exclusion criteria: contraindication to the use of TEA or TPVB, pregnancy, a history of cardiovascular and gastroesophageal surgery, preexisting pain syndrome, psychological disorders, coagulopathy, and severe hepatic, cardiovascular, or renal disorders. Standard posterolateral thoracotomy was chosen for all patients.

Surgery: elective thoracotomy

N total at baseline: Intervention: 42 Control: 41

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 60.6 ± 9.0 C: 63.0 ± 9.6

Sex (ratio F/M) I: 16/26 C: 9/32

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, the 2 groups of patients were comparable in surgical and demographic data

|

single-shot TPVB (ultrasound guided) combined with intravenous analgesia (P)

20 mL of 0.25% ropivacaine (Naropin, AstraZeneca, Gothenburg, Sweden) combined with 1 µg/kg dexmedetomidine (Ai Bei Ning, Jiangsu Hengrui Medicine, Lianyungang, China) was injected after a gentle aspiration test for blood or air (13,14).

In these patients, the intravenous PCA (sufentanil, basal rate of 0.03 µg/ kg/h, bolus dose of 0.01 µg/kg, lockout time 15 min) was used for 48 hours postoperatively.

|

continuous TEA (E)

epidural infusion of sufentanil (0.2 μg/mL) and ropivacaine 0.06% was started at 5–10 mL/h before the skin incision and maintained during the operation. Within 48 hours after the operation, the epidural patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) (0.06% ropivacaine + 0.2μg/mL sufentanil, basal rate was 5 mL/h, 3 mL PCA at a lock-out time of 30 minutes) was used. |

Length of follow-up: 12 months post operation

Loss-to-follow-up: Before allocation I: 3 (of 48) Reason did not receive allocated intervention due to inoperability (2) and reoperation (1)

C: 3 (of 48) Reason did not receive allocated intervention due to inoperability

After allocation Intervention:3 Reasons 3 death

Control: 4 Reasons 4 death

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention:0 Control: 0

|

Postoperative pain Verbal Rating Scale (VRS: 0 for no pain, and 10 for the worst pain) at rest and during coughing at 6, 24 and 48 h

Outcome data presented in box plots

6h at rest (median, IQR) I: 2 (0-3.5) In mean±SD I: 2 ± 0.875

24h at rest (median, IQR) I: 2 (2-4)

In mean±SD I: 2 ± 0.5

48h at rest (median, IQR) I: 2 (0,5-2,5)

In mean±SD I: 2 ± 0.5

><

6h at coughing (median, IQR) I: 2 (1-5)

In mean±SD I: 2 ± 1

24h at coughing (median, IQR) I: 5 (3-6)

In mean±SD I: 5 ± 0.75

48h at coughing (median, IQR) I: 3 (2-5)

In mean±SD I: 3 ± 0.75

Chronic pain Verbal Rating Scale (VRS: 0 for no pain, and 10 for the worst pain) at rest at 3, 6 and 12 months

Outcome data presented in box plots

3m at rest (median, IQR) I: 1 (0-2) 6m at rest (median, IQR) I: 0 (0-2)

12m at rest (median, IQR) I: 0 (0-1)

|

Study objective: to evaluate the impact of single-shot TPVB combined with intravenous analgesia versus continuous thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) on chronic pain incidence after thoracotomy

Study conclusion: In conclusion, our results show that patients who received continuous TEA had less acute pain intensity within 24 hours after operation and lower chronic pain incidence at rest at 3 and 12 months postoperation when compared with single-shot TPVB combined with intravenous analgesia. In addition, acute pain intensity within 24 hours postoperation appears to be a predictor of chronic pain. Therefore, these results suggest the importance of aggressive management of acute pain postoperation, not only for the immediate benefit but possibly also to prevent the transition to chronicity. |

|

Tamura, 2017 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single centre, Japan

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: lung cancer patients scheduled for elective single-side lung lobectomy with antero- or verticalaxillary incision were recruited during an 18-month period. The patients were aged 20–80 years and had an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status of I–II.

Exclusion criteria: The exclusion criteria were the same as those in our previous study [10] with the following additional criteria applied: combined resection of parietal pleura, coagulation disorder, thrombocytopenia, anti-coagulation therapy, and heart failure

Surgery: single-side lung lobectomy

N total at baseline: (analyses) Intervention: 36 Control: 36

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 67.1 ± 8.7 C: 66.9 ± 9.7

Sex (male:female): I: 29:7 C: 28:8

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes, demographic data and surgical characteristics, including duration of anesthesia, operation, and hospitalization, were comparable in both groups

|

PVB catheter (P)

20 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine was administered as a bolus, followed by a 300-mL of continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine at 5 mL/h

|

Epidural catheter (E)

5 mL of 0.375% ropivacaine (Anapeine injection; AstraZeneca K.K.) was administered as a bolus, followed by a 300-mL continuous infusion of 0.2% ropivacaine using an infusion pump (Multirate Infusor LV; Baxter Healthcare Co. Inc., Deerfield, IL) at 5 mL/h

|

Length of follow-up: 42h

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 4 of 40 Reason: withdrawal

Control: 4 of 40 Reason: withdrawal

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 0 Control: 0

|

Postoperative pain visual analog scale (VAS) while coughing, moving, and at rest 2 h after the bolus injection of ropivacaine; these evaluations were also performed at 1, 6, 12, 18, and 42 h after the injection. The VAS consisted of a 100-mm line (0 mm, no pain; 100 mm, worst pain imaginable).

Outcome data presented in line charts that are not readable.

All mean VAS scores in group E were significantly lower than those in group P throughout the observation period.

|

Study objective: to evaluate analgesic efficacy between paravertebral block via the surgical field (PVB-sf), in which the catheter was inserted into the ventral side of the sympathetic trunk in the paravertebral space by a thoracic surgeon under thoracoscopic visualization, and epidural block (Epi) using ropivacaine for post-thoracotomy pain relief

Study conclusion: In conclusion, Epi was superior to PVB-sf, in which the catheter was inserted into the ventral side of the sympathetic trunk in the paravertebral space, for post-thoracotomy pain management, as indicated by differences in the effective sensory block range of local anesthetics. |

|

PVB versus Epidural anesthesia - VATS |

|||||||

|

Ding, 2018 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single centre, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding: First Excellent Young People Project of the Second Hospital of Harbin Medical University IC: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. |

Inclusion criteria: patients classified as American Society of Anesthesiology Physical Status I/III undergoing elective video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Patients included in the study were between the ages of 18 and 70 years; had no neurologic or psychiatric illnesses, renal or hepatic insufficiency, pregnancy, diabetes, allergy to local anesthetics, or coagulation abnormalities; and were not undergoing anticoagulant therapy.

Exclusion criteria: Not reported

Surgery: elective video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy

N total at baseline: (analyses) Intervention: 36 Control: 32

Important prognostic factors2: For example age ± SD: I: 56.7 ± 9.3 C: 53.1 ± 10.9

Sex (% male): I: 63.9 C: 46.9

Groups comparable at baseline? There were no differences between groups in terms of patient, surgery, and PVB characteristics and intraoperative data

|

single-dose thoracic paravertebral analgesia

single-dose 0.5% ropivacaine PVB before the operation combined with the PCIA (0.01 μg/kg demand dose and 15 min lockout period with 0.03 μg/kg/h background infusion) after extubation during the 48-h postoperative period |

Thoracic epidural analgesia

intraoperative thoracic epidural anesthesia with 0.5% ropivacaine and a single dose of epidural morphine (0.03 mg/kg) after extubation, combined with the same PCIA scheme. |

Length of follow-up: 48h

Loss-to-follow-up: I: 2 Reasons: 1 thoractomy, 1 sensory block level did not reach the required level

C: 3 Reasons: 2 thoractomy, 1 sensory block level did not reach the required level

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention:0 Control: 0

|

Postoperative pain Verbal rating score (VRS; scale of 0–10, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating the worst pain imaginable) was assessed at 2, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after surgery at rest and after coughing.

Data in figure, not readable

Postoperative opioid consumption total dose of sufentanil used during the 48-h postoperative period

Data in figure, not readable

Adverse events Hypotension n (%) I: 5, 13.9 C: 11, 34.4

|

Study objective: to investigate the postoperative analgesic effect of TEA, PVB, and PVB with dexmedetomidine in patients undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy |

|

Kosiński, 2016 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single centre, Poland

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: patients qualified for VATS lobectomy due to cancer, aged 18-85 years, of both genders, ASA I-III, an understanding of the principles of VAS pain assessment and no chronic pain

Exclusion criteria: technical failures to insert an epidural or paravertebral catheter, abandonment of resection (e.g., in cases of neoplastic dissemination), conversion of VATS to thoracotomy, anatomical obstacles to drug distribution found intraoperatively, cases in which the VAS assessment of pain severity was infeasible (e.g., postoperative delirium), use of other drugs affecting pain sensations, artificial lung ventilation, discontinuation of local anaesthesia for technical reasons (e.g., catheter slipping out or damage), and the use of drugs or doses that were not included in the study protocol.

Surgery: Video-assisted (VATS) lung lobectomy

N total at baseline: (for analysis) Intervention: 26 Control: 25

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean (range): I: 64.7 (44–73) C: 59.9 (28–78)

Sex (female): I: 12 (46%) C: 10 (40%)

Groups comparable at baseline? yes

|

PVB

continuous infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine, intravenous ketoprofen and paracetamol |

TEA

continuous infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine with epinephrine, intravenous ketoprofen and paracetamol

|

Length of follow-up: 72h

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 11 Reasons: 1 failure of installation; 7 lesser extent of resection; 1 non-standard technique; 1 postoperative artificial ventilation; 1 technical failure.

Control: 16 Reasons: 7 failure of installation; 1 resection abandonment; 1 lesser extent of resection; 3 conversions to thoracotomy; 1 postoperative artificial ventilation; 2 violations of protocol; 1 technical failure.

Incomplete outcome data: n.a.

|

Postoperative pain VAS was evaluated 1, 4, 8, 24, 36, 48 and 72 h after the procedures using a standard ruler. In each case, static (at rest) and dynamic assessments (on cough).

data provided in graphs, not readable.

Significant differences were found in the measurements at 24 h — both at rest and on coughing (P = 0.01 and P = 0.023, respectively) — and in static pain at 36 h and 48 h (P = 0.025 and P = 0.026, respectively).

Postoperative opioid consumption Postoperative morphine dosage (Emergency PCA-administered morphine doses (mg h-1))

data provided in graphs, not readable.

The comparative analysis of both groups did not reveal any significant differences in the postoperative morphine dosage. The mean dose was 0.4 mg h-1 on day 0, 0.37 mg h-1 on day 1, 0.21 on day 2 and 0.14 mg h-1 on day 3

Adverse events I: 2 C: 8

|

epidural blocks were performed using the classic paramedian approach technique, whereas paravertebral blocks were performed according to the Eason and Wyatt method.

Study objective: to compare the analgaesic efficacy of continuous thoracic epidural block (TEA) and percutaneous continuous paravertebral block (PVB) in patients undergoing video-assisted lung lobectomy.

Study conclusion: 1. Pain following VATS lobectomy is severe and requires the use of complex techniques of postoperative analgaesia, including the methods of regional anaesthesia. 2. Continuous paravertebral block using the classical landmark puncture technique is as equally effective as epidural block for multimodal analgaesia. 3. Continuous paravertebral block has a better profile of safety than epidural block, which is particularly visible in the lower incidences of hypotension and urinary retention |

|

Lai, 2021 |

Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: single centre, China

Funding and conflicts of interest: funding: not reported, CI: All authors have no conflict of interests to declare. |

Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18–80 years old who were undergoing VATS lobectomy, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status class I–III, an understanding of the principle of visual rating scale (VAS) pain assessment and no chronic pain.

Exclusion criteria: patients who were on anticoagulation, patients taking opioids for greater than three weeks prior to surgery, patients with a contraindication to regional anesthesia such as infection close to the site of puncture, allergy to local anesthetics, and those with a history of chronic pain, severe cardiovascular disease, liver or renal insufficiency, a change in surgery type, conversion of VATS to thoracotomy, accidental catheter slipping, and patient refusal.

Surgery: VATS lobectomy