Screeningtools chronische pijn

Uitgangsvraag

Welke screeningtools zijn geschikt om chronische pijn te voorspellen bij kinderen?

Aanbeveling

Gebruik geen screeningtool om chronische pijn bij kinderen te voorspellen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

In de systematische literatuuranalyse werden twee studies geïncludeerd die de validiteit van de Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) onderzochten in Amerikaanse populaties. De PPST is een 9 punts vragenlijst over de invloed van pijn op het dagelijks leven gedurende de afgelopen twee weken. Helaas werd in deze studies niet de validiteit en betrouwbaarheid van de PPST onderzocht voor het voorspellen van chronische pijn, maar werden de uitkomsten van de tool vergeleken met andere metingen voor pijnkarakteristieken (zoals bijvoorbeeld hoge pijn frequentie of persisterende duur van pijn) en/of biopsychosociale risicofactoren (zoals bijvoorbeeld pijn catastroferen, pijn-gerelateerde angst of depressieve symptomen). Daardoor konden geen conclusies worden getrokken over de waarde van de PPST in het voorspellen van chronische pijn bij kinderen.

Sil onderzocht in de USA bij 73 patiënten met sikkelcelziekte tussen de 8-18 jaar in een derde lijnssetting de PPST in relatie tot meerdere tools die pijn of de impact van chronische pijn meten op verschillende domeinen. De gerapporteerde resultaten wijzen op een significante onderscheidende/discriminate betrouwbaarheid van de PPST op de domeinen pijnfrequentie, pijnvrije dagen, pijngerelateerde angst, matige tot ernstige lichamelijke beperking en pijninterferentie.

Simons onderzocht in Engeland de test-retest betrouwbaarheid en de validiteit PPST bij 321 patienten tussen de 8-18 jaar met veelal musculoskletale pijn of een complex regionaal pijn syndroom met de bedoeling tot een risicostratificatie te komen voor inzet van adequate behandeling. De gerapporteerde resultaten wijzen op een acceptabele test-retest betrouwbaarheid na 2 weken. De onderscheidende/discriminate betrouwbaarheid van de PPST was significant op het domein pijngerelateerde angst.

Er werden ook geen studies gevonden die andere screeningtools voor chronische pijn onderzochten. De werkgroep concludeert dan ook dat er een kennislacune bestaat omtrent de waarde van screeningtools in het voorspellen van chronische pijn bij kinderen.

De gevonden/gerapporteerde resultaten leveren onvoldoende bewijs om conclusies te kunnen trekken m.b.t. de validiteit en betrouwbaarheid van de PPST in het voorspellen van chronische pijn bij kinderen.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor kinderen en hun ouders/verzorgers is het van belang dat chronische pijn met een screeningtool zou kunnen worden opgespoord, zodat dit zou kunnen resulteren in snellere en betere pijnbestrijding. Ook zou dit mogelijkheden kunnen bieden voor het voorkomen van chronische pijn.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Kosten zijn hier niet van toepassing.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie is hier niet van toepassing, omdat geen aanbevelingen worden gedaan een bepaald screeninginstrument is implementeren.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Vooralsnog is er geen evidence dat de toegevoegde waarde van een screeningtool voor chronische pijn ondersteunt. Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) kan mogelijk wel gebruikt worden als meetinstrument van pijn. Dit zal in latere modules aan de orde komen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Bij een deel van de kinderen met acute pijn ontstaan aanhoudende en dus chronische pijnklachten. Toepassing van een screeningtool gericht op het identificeren, kwalificeren en kwantificeren van chronische pijn bij kinderen kan resulteren in snellere en betere pijnbestrijding. Het doel van deze module is om screeningtools voor het voorspellen van chronische pijn bij kinderen in kaart te brengen.

Conclusies

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the validity (construct validity, criterion validity) and reliability of the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) for predicting chronic pain in children.

Sources: Sil, 2019; Simons, 2015 |

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the measurement error and responsiveness of the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) for predicting chronic pain in children.

Sources: - |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Sil (2019) evaluated the validation of the Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST) compared to a standardized battery of well-validated patient-reported outcomes in children aged 8 to 18 years old presenting with sickle cell disease (SCD) to three outpatient SCD clinic locations of a tertiary care children’s hospital. The PPST is short 9-item self-report questionnaire developed for rapid identification of risk in youth with pain complaints. Total scores ranged from 0 to 9 and included two subscales: physical (range 0 to 4) and psychosocial (range 0 to 5). Chronic SCD pain was defined as pain frequency (range 1 (only this month to 5 (over 1 year)) ≥15 days per month with duration ≥6 months. Pain interference was measured with the PROMIS Pediatric Pain Interference Short Form, whereby total score (range 0-32) were transformed to T-scores (higher T-score indicate greater pain interference). Cases were defined as pain interference T-score ≥65. Pain catastrophizing was measured with the Pain Catastrophizing Scale – Child (PCS-C), whereby total scores (range 0 to 52) were categorized as: low (0–14), moderate (15–25), and high (≥ 26). Cases were defined as PCS-C≥26. ROC curve analysis was used to evaluate the potential utility of the PPST to detect diagnostically or clinically significant levels of risk or disorder and develop cutoff scores to allocate patients into a risk group. Utility was determined by the PPST’s ability to be both sensitive and specific to detecting risk, as determined by the area under the curve (AUC) metric. A total of 73 children completed study procedures and were included in the analysis. The mean age was 14.3 (SD 2.61) years old, 43% was male and 94% was black or African American.

Simons (2015) evaluated the variability and test-retest reliability of the PPST after 4 months in children aged 8 to 18 years old who presented for a multidisciplinary pain clinic evaluation at a Chronic Pain Clinic between January 2012 and April 2014 in the USA. Follow-up measures were taken at 2-weeks and 4-weeks. All patients participated in a multidisciplinary pain clinic evaluation, where the patient and parent(s) jointly met with a physician and physical therapist, and clinical psychologist for two separate one-hour sessions. The outcomes of interest after 4-month follow up were functional disability, fear, catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety. Functional disability was measured by the 15-item Functional Disability Inventory (FDI), whereby higher total scores indicated greater disability: moderate (score 13-29) and severe (score ≥ 30) disability. Fear was measured by the 24-item Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FOPQ) for children, whereby total scores ≥51 were classified as high pain-related fear. Pain catastrophizing was measured by the 13-item Pain Catastrophizing Scale Child report (PCS-C]), whereby scores ≥26 were classified as high catastrophizing. Depression was measured by the 28-item Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), whereby T-scores ≥ 65 were classified as clinically significant. Anxiety was measured by the 45-item Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale, whereby total T-scores ≥ 60 were defined as clinically significant. Discriminant validity was examined by calculating the area under the curve (AUC) for the overall PPST score against ‘cases’ on relevant reference standards. Predictive validity of the PPST risk groups at baseline (low risk: total score 0-2; medium risk: total score ≥ 3 with psychosocial score 0-2; high risk: total score ≥ 3 with psychosocial score ≥ 3) was examined by chi-square and one-way ANOVA to examine differences across the groups based on frequency of reference standard cases and continuous scores at 4-month follow-up. A total of 321 children were enrolled in the study. The mean age was 13.7 (SD 2.47) years old, 25% was male and 90% was Caucasian. Most children had musculoskeletal pain (43.2%) or complex regional pain syndrome (18.6%). The duration of pain ranged from <1 month to >15 years (mean 13 months).

Results

1. Validity (critical outcome)

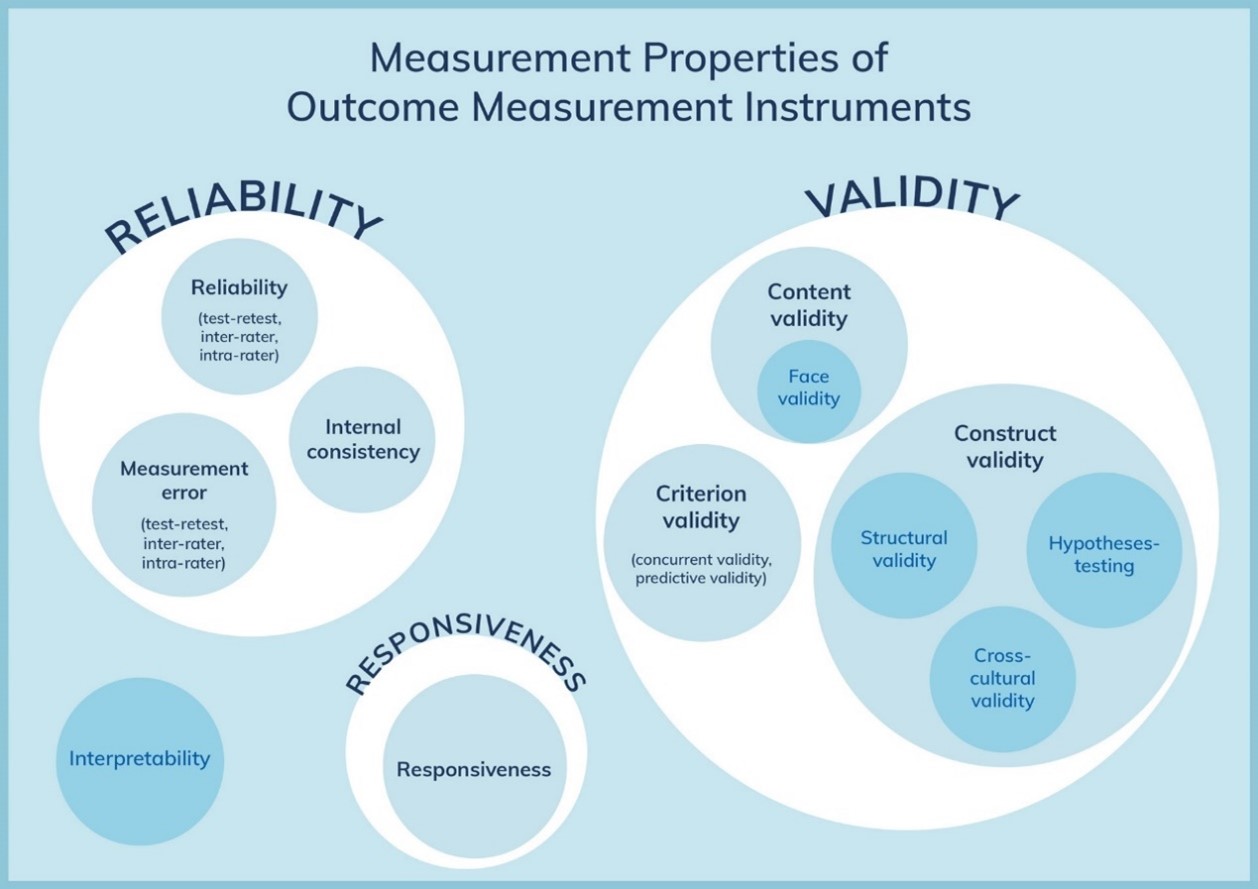

The domain validity refers to the degree to which an outcome measure measures the construct it purports to measure and contains the measurement properties content validity (including face validity), construct validity (including structural validity, hypotheses testing, and cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance) and criterion validity.

1.1 Construct validity

1.1.2. Discriminate validity

In both studies, the area under the curve (AUC) for the overall PPST score against reference standard cases were derived to examine how well the screening tool could discriminate cases from non-cases of different measures at baseline (table 1).

In the study of Sil (2019), the AUC for the PPST total score significantly discriminated cases from non-cases excellent for high pain frequency (AUC = 0.82; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.93), burden days frequency (AUC = 0.83; 95% CI 0.74 to 0.92), high pain-related fear (AUC = 0.93; 95% CI 0.87-0.98), moderate to severe disability (AUC = 0.93; 95% CI 0.87 to 0.98) and high pain interference (AUC = 0.80; 95% CI 0.68 to 0.93). The AUC for the PPST total score was acceptable for high pain catastrophizing (AUC = 0.75; 95% CI 0.64 to 0.86) and high admissions for pain (AUC = 0.74; 95% CI 0.62 to 0.86). The AUC was poor for persistent pain duration (AUC = 0.65; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.77) and high ED visits for pain (AUC = 0.69; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.82).

In the study of Simons (2015), the AUC for the PPST total score significantly discriminated cases from non-cases excellent for high pain-related fear (AUC = 0.80; 95% CI 0.74 to 0.85). The AUC for the PPST total score was acceptable for disability (AUC = 0.72; 95% CI 0.65 to 0.79), depression (AUC = 0.78; 95% CI 0.72 to 0.84) and anxiety (AUC = 0.74; 95% CI 0.67 to 0.81), and poor for high pain catastrophizing (AUC = 0.68; 95% CI 0.62 to 0.74).

Table 1. Discriminate validity: Area under the curve (AUC) for the PPST total scores against reference standard cases.

|

Study |

Measures |

Definition |

Total scores AUC (95% CI) |

|

Sil, 2019 |

Pain characteristics |

|

|

|

|

High pain frequency |

Pain frequency ≥ 15 days/month |

0.82 (0.71-0.93) |

|

|

Burden days frequency |

SCD pain burden days ≥ many |

0.83 (0.74-0.92) |

|

|

Persistent pain duration |

Duration ≥ 6 months |

0.63 (0.50-0.77) |

|

|

Biopsychosocial risk factors |

|

|

|

|

High pain catastrophizing |

PCS-C ≥ 26 |

0.75 (0.64-0.86) |

|

|

High pain-related fear |

FOPQ ≥ 13 |

0.93 (0.87-0.98) |

|

|

High pain interference |

Pain interference T-score ≥ 62 |

0.80 (0.68-0.93) |

|

|

High admissions for pain |

Admissions for pain ≥ 3 |

0.74 (0.62-0.86) |

|

|

High ED visits for pain |

ED visits for pain ≥ 3 |

0.69 (0.55-0.82) |

|

|

Moderate to severe disability |

FDI ≥ 13 |

0.93 (0.87-0.98) |

|

|

Elevated depressive symptoms |

CDI T-score ≥ 65 |

0.76 (0.63-0.88) |

|

Simons, 2015 |

Biopsychosocial risk factors |

|

|

|

|

Disability |

FDI ≥ 13 |

0.72 (0.65−0.79) |

|

|

High pain catastrophizing |

PCS-C ≥ 26 |

0.68 (0.62−0.74) |

|

|

High pain-related fear |

FOPQ ≥ 51 |

0.80 (0.74−0.85) |

|

|

Depression |

CDI T-score≥ 65 |

0.78 (0.72−0.84) |

|

|

Anxiety |

RCMAST-score ≥ 60 |

0.74 (0.67−0.81) |

CDI, Children’s Depression Inventory; FDI, Functional Disability Inventory; FOPQ, Fear of Pain Questionnaire; PCS-C, Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Children; RCMAS, Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale

1.2 Criterion validity

1.2.1 Predictive validity

Unfortunately, chronic pain was not evaluated in the included studies. Therefore, we report only the predictive validity of the PPST for indirect outcomes.

Simons (2015) examined the predictive ability of PPST risk groups defined at baseline on disability, fear, catastrophizing, depression, and anxiety outcomes at 4-month follow-up. However, the cutoff scores for the PPST risk groups were based on ROC curves for disability and psychosocial distress in the study sample. The low-risk group was defined as a PPST total score of 0-2, the medium-risk group was defined as a PPST total score ≥ 3 with psychosocial score 0-2. The high-risk group was defined as a PPST total score ≥ 3 with psychosocial score ≥ 3. A small percentage (ranging from 2 to 7%) classified as low risk at baseline were cases at 4-months follow up. A high percentage (ranging from 71 to 78%) classified as high risk at baseline were cases at 4-month follow-up (table 2).

Table 2. Predictive validity: Chi-square values of frequency of cases at follow-up by baseline risk group in Simons (2015)

|

|

Baseline Risk Group PPST |

|

||

|

Biopsychosocial risk factors |

Low N (%) |

Medium N (%) |

High N (%) |

Chi-square value |

|

High pain catastrophizing |

4 (6) |

11 (16) |

54 (78) |

17.1** |

|

High fear of pain |

2 (4) |

9 (18) |

40 (78) |

11.6** |

|

Moderate to severe disability |

2 (2) |

24 (26) |

65 (71) |

20.2** |

|

Clinically anxious |

2 (7) |

4 (14) |

23 (79) |

5.84* |

|

Clinically depressed |

1 (2) |

9 (20) |

36 (78) |

6.11* |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

1.2.2. Concurrent validity

In Sil (2019), the differences across the PPST risk groups based on frequency of cases on pain and biopsychosocial measures were evaluated cross sectionally only.

A low percentage (ranging from 0 to 7% for most measures, with an outlier of 22% for persistent pain duration) classified as PPST low-risk were cases. The percentage cases classified as PPST high-risk ranged from 48 to 71% (table 3).

Table 3. Concurrent validity: Chi-square values of frequency of cases by risk group (cross-sectional) in Sil (2019)

|

|

Risk Group PPST |

|

||

|

Pain characteristics |

Low N (%) |

Medium N (%) |

High N (%) |

Chi-square value |

|

High pain frequency |

0 (0) |

4 (29) |

10 (71) |

13.52*** |

|

Burden days frequency |

0 (0) |

7 (30) |

16 (70) |

23.96*** |

|

Persistent pain duration |

7 (22) |

10 (31) |

15 (47) |

3.97 |

|

Biopsychosocial risk factors |

|

|

|

|

|

High pain catastrophizing |

2 (7) |

14 (45) |

15 (48) |

13.17*** |

|

High pain-related fear |

1 (3) |

14 (44) |

17 (53) |

20.56*** |

|

High pain interference |

1 (6) |

4 (24) |

12 (71) |

14.89*** |

|

High admissions for pain |

1 (5) |

7 (37) |

11 (58) |

9.84** |

|

High ED visits for pain |

1 (7) |

6 (43) |

7 (50) |

4.45 |

|

Moderate to severe disability |

0 (0) |

13 (39) |

20 (61) |

31.43*** |

|

Elevated depressive symptoms |

0 (0) |

6 (40) |

9 (60) |

9.67** |

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001

2. Reliability (important outcome)

The domain reliability refers to the degree to which the measurement is free from measurement error, and it contains the measurement properties internal consistency, reliability, and measurement error. Reliability was only reported in Simons (2015).

2.1 Test-retest reliability

Simons (2015) investigated test-retest reliability, 2-weeks after evaluation a subset of patients received and completed the PPST (n=221). Intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) using a two-way random effects ANOVA model (participant x time-point) were calculated. The ICC was 0.75 for the total PPST score and 0.70 for the psychosocial subscale, demonstrating an acceptable 2-week test-retest reliability.

Table 4. Results of the measurement properties of PPST

|

Author, year |

Country (language) in which the questionnaire was evaluated |

Reliability |

Criterion validity |

Hypotheses testing (construct validity) |

|||||||

|

n |

Meth qual* |

Result (rating)** |

n |

Meth qual* |

Result (rating)** |

n |

Meth qual* |

Result (rating)** |

|||

|

Sil, 2019 |

US (English) |

|

|

|

73 |

Inadequate |

Correlation not calculated for chronic pain (?) |

73 |

Inadequate |

No hypothesis tested for chronic pain (-) |

|

|

Simons, 2015 |

US (English) |

221

|

Inadequate |

PPST total score: ICC = 0.75 PPST psychosocial subscale: ICC = 0.70 (+) |

195 |

Inadequate |

Correlation not calculated for chronic pain (?) |

195 |

Inadequate |

No hypothesis tested for chronic pain (-) |

|

|

Pooled or summary result (overall rating) |

221 |

Inadequate |

ICC≥0.7 (+) |

168 |

Inadequate |

Correlation unknown (?) |

168 |

Inadequate |

No hypothesis tested for chronic pain (-) |

||

*Risk of bias assessment based on COSMIN risk of bias tool: lowest score counts

**Measurement properties of each study could be rated as: sufficient (+), insufficient (–), or indeterminate (?)

Level of evidence of the literature

Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST)

The level of evidence regarding the construct validity was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (2 levels, because there are 2 studies of inadequate quality); and indirectness (1 level, because different construct is measured; no chronic pain) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the criterion validity was downgraded by 3 levels because of risk of bias (2 levels, because there are 2 studies of inadequate quality); and indirectness (1 level, because different construct is measured; no chronic pain) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the reliability was downgraded by 3 levels because of extremely serious risk of bias (3 levels, because there is only 1 study of inadequate quality available); and indirectness (1 level, because different construct is measured; no chronic pain) to VERY LOW.

The level of evidence regarding the measurement error was not assessed because no studies were included investigating this outcome.

The level of evidence regarding the responsiveness was not assessed because no studies were included investigating this outcome.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the validity and reliability of screening tools for predicting chronic pain in children?

P: Children 0-18 years old

I: Screening tools for predicting chronic pain, such as Bapq, Pcs, Hads, Rcads

C: Screening tools compared to each other (if relevant)

O: Validity, reliability

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered validity as a critical outcome measure for decision making; and reliability as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The measurement properties were defined following the taxonomy of the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) (Mokkink, 2010).

The working group defined the discriminate validity of the screening tools as follows:

AUC < 0.7: poor; 0.7 ≤ AUC < 0.8: acceptable; 0.8 ≤ AUC < 0.9: excellent; AUC ≥ 0.9: outstanding. The working group defined the reliability of the screening tools as follows: ICC < 0.5: poor; 0.5 ≤ ICC < 0.75: moderate; 0.75 ≥ ICC < 0.9: good; ICC≥ 0.9: excellent.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 25 November 2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 898 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Being a systematic review, randomized controlled trial (RCT) or observational study (cohort study).

- Reporting the validity and/or reliability of a screening tool for predicting chronic pain in children aged 0 to 18 years old.

Seven studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, five studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables. The COSMIN Risk of Bias tool was used to assess the quality of single studies for each measurement property (see Methods section in ‘Verantwoording’).

Referenties

- 1 - Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Stratford, P. W., Knol, D. L., ... & de Vet, H. C. (2010). The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 63(7), 737-745.

- 2 - Mokkink, L. B., Prinsen, C., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., de Vet, H. C., ... & Mokkink, L. (2018). COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). User manual, 78(1).

- 3 - Sil, S., Cohen, L. L., & Dampier, C. (2019). Pediatric pain screening identifies youth at risk of chronic pain in sickle cell disease. Pediatric blood & cancer, 66(3), e27538.

- 4 - Simons, L. E., Smith, A., Ibagon, C., Coakley, R., Logan, D. E., Schechter, N., ... & Hill, J. C. (2015). Pediatric Pain Screening Tool (PPST): Rapid identification of risk in youth with pain complaints. Pain, 156(8), 1511.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention Screening Tool |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Sil, 2019 |

Type of study: cross-sectional study

Setting and country: outpatient Pediatric sickle cell disease clinic, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: not reported |

Inclusion criteria: children and adolescents 8 to 18 years old with SCD (any genotype), English-speaking, presenting to outpatient comprehensive SCD clinics at three campus locations of a tertiary care children’s hospital over 14 months. Patients receiving active treatment with hydroxyurea or transfusion for pain.

Exclusion criteria: significant documented cognitive or developmental disabilities, chronic transfusions indicated for central nervous system complications (e.g., stroke), or comorbid medical condition in which pain is common (e.g., rheumatological or gastrointestinal conditions).

N total at baseline: 93

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean ± SD: 14.3 ± 2.61

Sex: 42.5% M

Race: 94.3% black or African American |

Pediatric Pain Screening Tool 9 items with question “Thinking about the last 2 weeks check your response to the following statements.” Answering yes (score 1) or no (score 0). Total score range from 0 to 9.

Physical Subscale

Psychosocial Subscale

Overall, how much has pain been a problem in the last 2 weeks?

|

Pain frequency ≥ 15 days/month SCD pain burden days ≥ many Duration ≥ 6 months PCS-C ≥ 26 FOPQ ≥ 13 Pain interference T-score ≥ 62 Admissions for pain ≥ 3 ED visits for pain ≥ 3 FDI ≥ 13 CDI T-score ≥ 65

|

Length of follow-up: NA

Incomplete outcome data: 20 (21.5%) Reasons: barriers to participation were completing and returning surveys after completing verbal consent.

|

Discriminate validity, AUC (95% CI)

|

No comparison of PPST with chronic pain |

|

Simons, 2015 |

Type of study: prospective cohort study

Setting and country: Chronic Pain Clinic, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial funding. Conflict of interest not reported. |

Inclusion criteria: Children aged 8 to 18, presenting for a multidisciplinary pain clinic evaluation at the Chronic Pain Clinic at Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, USA (January 2012 to April 2014)

Exclusion criteria: None

N total at baseline: 321

Important prognostic factors2: Age, mean ± SD: 13.73 ± 2.47

Sex: 25% M |

Pediatric Pain Screening Tool

|

Disability: FDI ≥ 13 High pain catastrophizing: PCS-C ≥ 26 High pain-related fear: FOPQ ≥ 51 Depression: CDI T-score≥ 65 Anxiety: RCMAST-score ≥ 60

|

Length of follow-up: 4 months

Loss-to-follow-up, N (%) 126 (39%) Reasons not reported.

|

Discriminant validity total PPST score, AUC (95% CI)

Predictive validity total PPST score. Low / medium / high risk at baseline, n(%); chi-square value

Reliability total PPST score, ICC - Total PPST score: 0.75 - Psychosocial subscale PPST: 0.70 |

No comparison of PPST with chronic pain |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity |

|||||

|

Author: Simons, 2015 |

|||||

|

Instrument: PPST |

|||||

|

Discriminative / known-groups validity |

Very good |

Adequate |

Doubtful |

Inadequate |

NA |

|

Was an adequate description provided of important characteristics of the subgroups? |

Adequate description of the important characteristics of the subgroups |

Adequate description of most of the important characteristics of the subgroups |

Poor or no description of the important characteristics of the subgroups |

|

|

|

Was the statistical method appropriate for the hypothesis to be tested? |

Statistical method was appropriate |

Assumable that statistical method was appropriate |

Statistical method applied NOT optimal |

Statistical method applied NOT appropriate |

|

|

Were there any other important flaws in the design or statistical methods of the study? |

No other important methodological flaws |

|

Other minor methodological flaws (e.g. only data presented on a comparison with an instrument that measures another construct): fear of falling and fall frequency are self-reported |

Other important methodological flaws, no chronic pain measured |

|

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity |

|||||

|

Author: Sil, 2019 |

|||||

|

Instrument: PPST |

|||||

|

Discriminative / known-groups validity |

Very good |

Adequate |

Doubtful |

Inadequate |

NA |

|

Was an adequate description provided of important characteristics of the subgroups? |

Adequate description of the important characteristics of the subgroups |

Adequate description of most of the important characteristics of the subgroups |

Poor or no description of the important characteristics of the subgroups |

|

|

|

Was the statistical method appropriate for the hypothesis to be tested? |

Statistical method was appropriate |

Assumable that statistical method was appropriate |

Statistical method applied NOT optimal |

Statistical method applied NOT appropriate |

|

|

Were there any other important flaws in the design or statistical methods of the study? |

No other important methodological flaws |

|

Other minor methodological flaws (e.g. only data presented on a comparison with an instrument that measures another construct): fear of falling and fall frequency are self-reported |

Other important methodological flaws, no chronic pain measured |

|

|

Author: Simons, 2015 |

|||||

|

Instrument: PPST |

|||||

|

Criterion validity |

Very good |

Adequate |

Doubtful |

Inadequate |

NA |

|

For continuous scores: Were correlations, or the area under the receiver operating curve calculated? |

Correlations or AUC calculated |

|

|

Correlations or AUC NOT calculated |

Not Applicable, nominal scores |

|

For dichotomous scores: Were sensitivity and specificity determined? |

Sensitivity and specificity calculated |

|

|

Sensitivity and specificity NOT calculated |

Not Applicable, nominal scores |

|

Were there any other important flaws in the design or statistical methods of the study? |

No other important methodological flaws |

|

Other minor methodological flaws

|

Other important methodological flaws, no chronic pain measured, cutoff scores of PPST risk groups dependent of ROC curves in study sample |

|

|

Author: Sil, 2019 |

|||||

|

Instrument: |

|||||

|

Criterion validity |

Very good |

Adequate |

Doubtful |

Inadequate |

NA |

|

For continuous scores: Were correlations, or the area under the receiver operating curve calculated? |

Correlations or AUC calculated |

|

|

Correlations or AUC NOT calculated |

Not Applicable, nominal scores |

|

For dichotomous scores: Were sensitivity and specificity determined? |

Sensitivity and specificity calculated |

|

|

Sensitivity and specificity NOT calculated |

Not Applicable, nominal scores |

|

Were there any other important flaws in the design or statistical methods of the study? |

No other important methodological flaws |

|

Other minor methodological flaws

|

Other important methodological flaws, no chronic pain measured, only cross sectional results |

|

|

Reliability |

|||||

|

Author: Simons, 2015 |

|||||

|

Instrument: PPST |

|||||

|

Design requirements |

Very good |

Adequate |

Doubtful |

Inadequate |

NA |

|

1. Were patients stable in the interim period on the construct to be measured? |

Yes (evidence provided) |

Reasons to assume standard was met |

Unclear |

No (evidence provided): treatment was started after baseline measurement |

Na |

|

2. Was the time interval between the repeated measurements appropriate? |

Yes |

|

Doubtful, OR time interval not stated |

No |

Na |

|

3. Were the measurement conditions similar for the repeated measurements – except for the condition being evaluated as a source of variation? |

Yes (evidence provided) |

Reasons to assume standard was met, OR change was unavoidable |

Unclear |

No (evidence provided) |

Na |

|

4. Did the professional(s) administer the measurement without knowledge of scores or values of other repeated measurement(s) in the same patients? |

Yes (evidence provided) |

Reasons to assume standard was met |

Unclear |

No (evidence provided) |

|

|

5. Did the professional(s) assign scores or determine values without knowledge of the scores or values of other repeated measurement(s) in the same patients? |

Yes (evidence provided) |

Reasons to assume standard was met |

Unclear |

No (evidence provided) |

|

|

6. Were there any other important flaws in the design or statistical methods of the study? |

No |

|

Minor methodological flaws |

Yes, chronic pain not measured |

|

|

Statistical methods |

Very good |

Adequate |

Doubtful |

Inadequate |

|

|

7. For continuous scores: was an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) calculated? |

ICC calculated; the model or formula was described, and matches study design and the data |

ICC calculated but model or formula was not described or does not optimally match the study design OR Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient calculated WITH evidence provided that no systematic difference between measurements has occurred |

Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient calculated WITHOUT evidence provided that no systematic difference between measurements has occurred OR WITH evidence provided that systematic difference between measurements has occurred |

|

|

|

8. For ordinal scores: was a (weighted) kappa calculated? |

Kappa calculated; the weighting scheme was described, and matches the study design and the data |

Kappa calculated, but weighting scheme not described or does not optimally match the study design |

|

|

NA |

|

9. For dichotomous/nominal scores: was Kappa calculated for each category against the other categories combined? |

Kappa calculated for each category against the other categories combined |

|

|

|

NA |

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Title |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Westbom, 2017 |

Assessments of pain in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: a retrospective population-based registry study |

Wrong study design: no validation of screening instrument. Only comparison between pain assessment and medical record |

|

Jakobsson, 2012 |

The Pain Impact Inventory-Further Validation in Various Subgroups |

Wrong P: patients aged 18 to 102 y old |

|

Guite, 2011 |

Readiness to change in pediatric chronic pain: Initial validation of adolescent and parent versions of the Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire |

Wrong I: PSOCQ to measure parental readiness to change (how parents perceive themselves ready to endorse the self-management philosophy). |

|

Beneciuk, 2018 |

Prediction of Persistent Musculoskeletal Pain at 12 Months: A Secondary Analysis of the Optimal Screening for Prediction of Referral and Outcome (OSPRO) Validation Cohort Study |

Wrong P: patients aged 18 to 65 y old |

|

Ruehlman, 2010 |

Psychosocial Correlates of Chronic Pain and Depression in Young Adults: Further Evidence of the Utility of the Profile of Chronic Pain: Screen (PCP: S) and the Profile of Chronic Pain: Extended Assessment (PCP: EA) Battery |

Wrong P: students aged 17 to 24 y old; wrong study design: depression association with pain attitude |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 10-05-2023

Laatst geautoriseerd : 10-05-2023

Geplande herbeoordeling :

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS).

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kinderen met pijn.

Kernwerkgroep

- Drs. M.A. (Maarten) Mensink, kinderanesthesioloog en pijnarts, werkzaam in het Prinses Máxima Centrum voor Kinderoncologie te Utrecht, NVA, voorzitter

- Drs. J.F. (Joanne) Goorhuis, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het Medisch Spectrum Twente, NVK

- Dr. F (Felix) Kreier, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het OLVG te Amsterdam, NVK

- Drs. M.S. (Sukru) Genco, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het OLVG te Amsterdam, NVK

- Dr. S.H. (Steven) Renes, anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist, werkzaam in het Radboud UMC te Nijmegen, NVA

- Dr. P. (Petra) Honig-Mazer, psychotherapeut, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC Sophia te Rotterdam, PAZ/LVMP

- Drs. M. (Marjorie) de Neef, kinder-IC verpleegkundige, werkzaam in het Amsterdam UMC, V&VN

- R. (Rowy) Uitzinger, junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, tot 1 juni 2022

- E.C. (Esen) Doganer, junior projectmanager en beleidsmedewerker, Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis, vanaf 1 juni 2022

Werkgroep

- Drs. L.A.M. (Lonneke) Aarts, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het RadboudUMC Amalia kinderziekenhuis te Nijmegen, NVK

- Prof. dr. W.J.E. (Wim) Tissing, kinderoncoloog, werkzaam in het UMCG te Groningen en Prinses Máxima Centrum te Utrecht, NVK

- Prof. dr. S.N. (Saskia) de Wildt, kinderintensivist, werkzaam in het RadboudUMC te Nijmegen, NVK

- Prof. dr. N.M. (Nico) Wulffraat, kinderreumatoloog, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVK

- Drs. A.M. (Arine) Vlieger, algemeen kinderarts, werkzaam in het St. Antonius Ziekenhuis te Utrecht, NVK

- Dr. S.H.P. (Sinno) Simons, kinderarts-neonatoloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC Sophia te Rotterdam, NVK

- Drs. K. (Karina) Elangovan, kinderanesthesioloog, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC Sophia te Rotterdam, NVA

- Dr. C.M.G. (Claudia) Keyzer – Dekker, kinderchirurg, werkzaam in het Erasmus MC Sophia te Rotterdam, NVvH

- T. (Thirza) Schuerhoff, pedagogisch medewerker, werkzaam in het Prinses Máxima Centrum voor Kinderoncologie te Utrecht, Vakgroep Medische Pedagogische zorg

- A.P. (Annette) van der Kaa, kinderfysiotherapeut, werkzaam in het Erasumc MC Sophia te Rotterdam, KNGF en NVFK

Klankbordgroep

- Drs. J. (Judig) Blaauw, kinderrevalidatiearts, VRA

- Dr. H. (Hanneke) Bruijnzeel, AIOS, werkzaam in het UMC Utrecht te Utrecht, NVKNO

- Dr. A.M.J.W. (Anne-Marie) Scheepers, ziekenhuisapotheker, werkzaam in het MUMC te Maastricht, NVZA

- Dr. S.A. (Sylvia) Obermann-Borst, ervaringsdeskundige ouder & huisarts-epidemioloog, Care4Neo (voorheen Vereniging van Ouders van Couveusekinderen - VOC)

- Dr. I.H. (Ilse) Zaal-Schuller, arts voor verstandelijk gehandicapten/kaderarts palliatieve zorg i.o., werkzaam bij Prinsenstichting Purmerend/ AmsterdamUMC locatie AMC, NVAVG

- C. (Charlotte) Langemeijer, CliniClowns Nederland

- M. (Miep) van der Doelen, CliniClowns Nederland

- Dr. E. (Eva) Schaffrath, anesthesioloog, werkzaam in het Maastricht UMC te Maastricht, PROSA Kenniscentrum

- M. (Mirjam) Jansen op de Haar, HME-MO Vereniging Nederland

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J. (Janneke) Hoogervorst – Schilp, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. C. (Cécile) Overman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van (kern)werkgroepleden en klankbordgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Betrokkenen |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Werkgroep |

||||

|

Aarts |

Algemeen kinderarts in het Amalia kinderziekenhuissinds november 2017 |

Interne functies onbetaald: 1. voorzitter Pijn werkgroep Amalia kinderziekenhuis. 2. Verbonden aan werkgroep procedurele sedatie bij kinderen. 3. Implementatie VR in Amalia. |

Onderzoek naar effect comfort talk technieken; maar eenmalige subsidie gekregen voor uitvoer. Geen extern belang qua uitkomst. |

Geen actie |

|

Blaauw |

Kinderrevalidatiearts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Bruijn, de (interim) |

Kinderrevalidatiearts bij Revalidatie Friesland |

Lid kwaliteitscommissie VRA (deels betaald, vacatiegeld) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Doelen |

CliniClown bij stichting CliniClowns 28 uur per week |

Bestuurslid theaterproducties Natuurtheater de Kersouwe in Heeswijk Dinther (onbetaald) |

Hoofddoel van mijn bijdrage aan de werkgroep is de kennis en ervaring van CliniClowns in te zetten bij het geven van feedback op de gemaakte stukken. |

Geen actie |

|

Elangovan |

Universitair medisch specialist Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist; ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Genco |

Kinderarts, OLVG, Amsterdam |

- Eigenaar Genco Med. Beheer B.V. |

Directe belangen bij eigen B.V. maar geen relatie met de bezigheden van de werkgroep. Bijvangst van het project kan zijn: nieuwe kennis en ervaring om binnen onze organisatie te delen. |

Geen actie |

|

Goorhuis |

Algemeen kinderarts - acute kindergeneeskunde |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Haar, van der |

Freelance consultant Moonshot |

Bestuurslid HME-MO Vereniging Nederland |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Kaa, van der |

Kinderfysiotherapeut |

-Docent Master Kinderfysiotherapie bij Breederode Hogeschool - Universitair docent -Kinderfysiotherapeut 1e lijn (Fysio van der Linden) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Keyzer-Dekker |

Kinderchirurg Sophia Kinderziekenhuis ErasmusMC te Rotterdam |

APLS instructeur SSHK Riel, dagvergoeding |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Kreier |

Kinderarts OLVG Amsterdam |

Medeauteur en -oprichter “De hamster in je brein” |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Mensink* |

kinderanesthesioloog - pijnarts - Prinses Máxima Centrum voor kinderoncologie |

Bestuurslid sectie Pijn&palliatieve geneeskunde NVA - onbetaalde functie |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Neef, de |

Verpleegkundig onderzoeker, Kinder IC, Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Petra Honig-Mazer |

Erasmus MC - Sophia Kinderziekenhuis Afdeling Kinder- en Jeugdpsychiatrie/psychologie Unit Psychosociale Zorg Psychotherapeut BIG |

Kleine eigen praktijk: Praktijk voor Psychotherapie Honig-Mazer, betaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Renes |

Anesthesioloog-pijnspecialist Radboudumc |

Kwaliteitsvisitaties Nederlandse Vereniging Anesthesiologie, vacatiegeld |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Schuerhoff |

Medisch Pedagogisch Zorgverlener |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Simons |

Kinderarts - neonatoloog - klinisch farmacoloog (Universitair Medische Specialist) |

Lid geneesmiddelencommissie Erasmus MC (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Tissing |

Kinderoncoloog, Hoogleraar supportive care in de kinderoncologie. 0.6 fte Prinses Maxima Centrum, 0,4 fte UMCG |

PI van onderzoek naar app over invloed van laagdrempelig contact op pijn bij patiënten met kanker. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Uitzinger |

Junior Project manager en beleidsmedewerker Stichting kind en ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vlieger |

1. Kinderarts St Antonius ziekenhuis Nieuwegein |

1. Les geven via Cure en Care en via het Prinses MAxima Centrum op het gebiedvan hypnose bij kinderen. Dit is betaald. |

Aangezien ik les geef op het gebied van non-farmacologische methoden om pijn en angst te voorkomen cq te behandelen kan ik daar theoretisch voordeel van ondervinden als nog meer afdelingen hun personeel geschoold wilt hebben in non-farmacologische technieken. in de richtlijn komen uiteraard geen namen van bedrijven te staan, dus ik verwacht geen evident voordeel. Mijn mede eigenaars van het skills4comfort bedrijf. Overigens loopt dit al heel goed. Iedereen is gelukkig al overtuigd van het belang van het aanleren van positief taalgebruik, afleiden, echt contact maken en een vertrouwensband opbouwen. |

Uitsluiten van besluitvorming voor modules over non-farmacologische pijnbestrijding. Mag wel meelezen. |

|

Wildt, de |

Kinderarts-intensivist, hoogleraar klinische farmacologie, Radboudumc |

Directeur stichting Nederlands Kenniscentrum Farmacotherapie Kinderen (detachering |

Patent: Gebruik van PENK voor nierfunctiebepaling bij kinderen (aangevraagd). Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation: model-informed dosing for pediatric dosing |

Geen actie |

|

Wulffraat |

Hoogleraar kinderimmunologie/reumatologie. UMCU |

Voorzitter (coordinator) ERN-RITA (european reference network (onbetaald). |

Onze vakgroep heeft zeer veel extern gefinancierd onderzoek. Er is geen direct belang van de financier bij deze richtlijn. Onderzoekslijn chronische pijn bij jeugdreuma is puur academisch. Mensink (aangesteld in PMC) is hier de promovendus. Ik ben de promotor. |

Geen actie |

|

Klankbordgroep |

||||

|

Bruijnzeel |

Arts-assistent Keel-, Neus- en Oorheelkunde, UMC Utrecht |

Kerngroep Pediatrie (KNO vereniging) - onbetaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Scheepers |

ziekenhuisapotheker, Maastricht UMC+ |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Obermann-Borst |

Coördinator Wetenschap bij Care4Neo 10 u per week |

Coördinator Wetenschap bij Care4Neo 75% betaald/25% vrijwillig verzorgen van bijdrage vanuit patientenperspectief aan wetenschap, richtlijnen en kwaliteit van zorg namens de patientenvereniging voor ouders van en voor kinderen die te vroeg, te klein en/of ziek geboren zijn. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Zaal Schuller |

Arts voor verstandelijk gehandicapten |

Arts voor verstandelijk gehandicapten, betaald. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Schaffrath |

Kinderanesthesioloog MUMC |

Faculty member PROSA (tegen dagvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

* Voorzitter

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door afvaardiging van Stichting Kind en Ziekenhuis in de kernwerkgroep en Care4Neo, CliniClowns Nederland en HME-MO Vereniging Nederland in de klankbordgroep. Op verschillende momenten is input gevraagd tijdens een invitational conference en bij het opstellen van het raamwerk. Het verslag van de invitational conference [zie aanverwante producten] is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de patiëntenorganisaties en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Voorafgaand aan de voorbereidende fase is een invitational conference georganiseerd over herkenning en behandeling van pijn binnen de kindzorg. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten. Daarnaast werd tijdens de voorbereidende fase van de richtlijn een schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie gehouden. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur en de beoordeling van de risk-of-bias van de individuele studies is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie https://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

Definitie |

|

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

COSMIN

The COSMIN Risk of Bias tool was used to assess the quality of single studies for each measurement property. Thereby, the worst-score-counts method was used to determine the risk of bias, this means that the lowest rating given in a box determines the final rating, i.e. the quality of the study. The result of each study on a measurement property (figure 1) were rated against the updated criteria for good measurement properties (Table 1). Each result was rated as either sufficient (+), insufficient (–), or indeterminate (?).

Table 1. Criteria for good measurement properties (Mokkink, 2018)

|

Measurement property |

Rating[1] |

Criteria |

|

Structural validity |

+ |

CTT: CFA: CFI or TLI or comparable measure >0.95 OR RMSEA <0.06 OR SRMR <0.08[2] IRT/Rasch: No violation of unidimensionality[3]: CFI or TLI or comparable measure >0.95 OR RMSEA <0.06 OR SRMR <0.08 AND no violation of local independence: residual correlations among the items after controlling for the dominant factor < 0.20 OR Q3's < 0.37 AND no violation of monotonicity: adequate looking graphs OR item scalability >0.30 AND adequate model fit: IRT: χ2 >0.01 Rasch: infit and outfit mean squares ≥ 0.5 and ≤ 1.5 OR Z-standardized values > ‐2 and <2 |

|

? |

CTT: Not all information for ‘+’ reported IRT/Rasch: Model fit not reported |

|

|

- |

Criteria for ‘+’ not met |

|

|

Internal consistency |

+ |

At least low evidence[4] for sufficient structural validity[5] AND Cronbach's alpha(s) ≥ 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or Subscale.[6] |

|

? |

Criteria for “At least low evidence for sufficient structural validity” not met |

|

|

- |

At least low evidence4 for sufficient structural validity5 AND Cronbach’s alpha(s) < 0.70 for each unidimensional scale or Subscale.6 |

|

|

Reliability |

+ |

ICC or weighted Kappa ≥ 0.70 |

|

? |

ICC or weighted Kappa not reported |

|

|

- |

ICC or weighted Kappa < 0.70 |

|

|

Measurement error |

+ |

SDC or LoA < MIC |

|

? |

MIC not defined |

|

|

- |

SDC or LoA > MIC |

|

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity |

+ |

The result is in accordance with the hypothesis[7] |

|

? |

No hypothesis defined (by the review team) |

|

|

- |

The result is not in accordance with the hypothesis |

|

|

Cross‐cultural validity\measurement invariance |

+ |

No important differences found between group factors (such as age, gender, language) in multiple group factor analysis OR no important DIF for group factors (McFadden's R2 < 0.02) |

|

? |

No multiple group factor analysis OR DIF analysis performed |

|

|

- |

Important differences between group factors OR DIF was found |

|

|

Criterion validity |

+ |

Correlation with gold standard ≥ 0.70 OR AUC ≥ 0.70 |

|

? |

Not all information for ‘+’ reported |

|

|

- |

Correlation with gold standard < 0.70 OR AUC < 0.70 |

|

|

Responsiveness |

+ |

The result is in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC ≥ 0.70 |

|

? |

No hypothesis defined (by the review team) |

|

|

- |

The result is not in accordance with the hypothesis OR AUC < 0.70 |

|

|

AUC: area under the curve, CFA: confirmatory factor analysis, CFI: comparative fit index, CTT: classical test theory, DIF: differential item functioning, ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient, IRT: item response theory, LoA: limits of agreement, MIC: minimal important change, RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, SEM: Standard Error of Measurement, SDC: smallest detectable change, SRMR: Standardized Root Mean Residuals, TLI = Tucker‐Lewis Index |

||

[1] “+” = sufficient, ” –“ = insufficient, “?” = indeterminate

[2] To rate the quality of the summary score, the factor structures should be equal across studies

[3] unidimensionality refers to a factor analysis per subscale, while structural validity refers to a factor analysis of a (multidimensional) patient‐reported outcome measure

[4] As defined by grading the evidence according to the GRADE approach

[5] This evidence may come from different studies

[6] The criteria ‘Cronbach alpha < 0.95’ was deleted, as this is relevant in the development phase of a PROM and not when evaluating an existing PROM.

[7] The results of all studies should be taken together and it should then be decided if 75% of the results are in accordance with the hypotheses

Figure 1. The COSMIN taxonomy of measurement properties (www.cosmin.nl)

The level of evidence of the literature was evaluated as described in the COSMIN user manual for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (Mokkink, 2018). The following four factors were taken into account: (1) risk of bias (i.e. the methodological quality of the studies), (2) inconsistency (i.e. unexplained inconsistency of results across studies), (3) imprecision (i.e. total sample size of the available studies), and (4) indirectness (i.e. evidence from different populations than the population of interest in the review). The quality of evidence could be downgraded with one level (e.g. from high to moderate evidence) if there is serious risk of bias, with two levels (e.g. from high to low) if there is very serious risk of bias, or with three levels (i.e. from high to very low) if there is extremely risk of bias. The quality of the evidence could be downgraded with one or two levels for inconsistency, imprecision (-1 if total N=50-100; -2 if total N<50) and indirectness.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE-methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, Williams JW Jr, Kunz R, Craig J, Montori VM, Bossuyt P, Guyatt GH; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008 May 17;336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ. 2008 May 24;336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139.

Schünemann, A Holger J [corrected to Schünemann, Holger J]. PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016 Oct;104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.