Effectiviteit medicatie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de effectiviteit van medicatie in aanvulling op een gecombineerde leefstijlinterventie, in de behandeling van volwassenen met obesitas of overgewicht in combinatie met een vergrote buikomvang en/of comorbiditeit?

Aanbeveling

- Overweeg gewichtsreducerende medicatie toe te voegen aan een gecombineerde leefstijlinterventie bij mensen met obesitas (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) of overgewicht (BMI ≥27 kg/m2) in combinatie met een vergrote buikomvang en/of co-morbiditeit (zie voor concrete adviezen tabel 13.1). Maak een keuze op basis van effectiviteit, prijs en comorbiditeit (zie module ‘Gepersonaliseerde zorg’). Overweeg een GLP1-analoog bij patiënten met Diabetes Mellitus type 2.

- Houd rekening met de contra-indicaties en potentiële bijwerkingen bij de keuze van een gewichtsreducerend medicijn.

- Stop met orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon/bupropion (gewichtsreducerende medicatie) als het gewichtsverlies na 12 weken gebruik van de maximaal verdraagbare dosis kleiner is dan 5%, conform de indicatiestelling in de bijbehorende SmPC.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er zijn in Nederland meerdere medicijnen geregistreerd voor behandeling van overgewicht bij volwassenen: orlistat, liraglutide, semaglutide en naltrexon/bupropion. Deze zijn alle vier meegenomen in de analyse. Alle geïncludeerde studies hebben de medicatie vergeleken met placebo, doorgaans in combinatie met een intensieve gecombineerde leefstijlinterventie. De kwaliteit van het bewijs voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat gewicht is beoordeeld als redelijk, door inconsistentie in de studieresultaten, en risico of bias in de studieopzet. Uit de literatuuranalyse blijkt dat het gebruik van medicatie naast een GLI een hoger gewichtsverlies geeft na een jaar. In de geraadpleegde literatuur bij orlistat ligt het gemiddelde gewichtsverlies ten opzichte van placebo rond de 2,5 kg, bij naltrexon/bupropion en liraglutide 3 mg rond de 5 kg, bij de semaglutide 2,4 mg rond de 12 kg. Er zijn geen goede trials waarbij de middelen onderling zijn vergeleken. Op basis van deze literatuur lijkt semaglutide het meest effectief. Het is op basis van deze literatuur niet mogelijk om een keuze te maken tussen liraglutide en naltrexon/bupropion, of een inschatting te maken bij welke patiënt welk middel het beste zou kunnen werken.

Studies met betrekking tot liraglutide en semaglutide zijn uitgevoerd in een homogene groep. Uit deze studies kunnen we opmaken dat het middel niet bij iedereen even effectief werkt. Het behaalde gewichtsverlies kan variëren van zeer weinig tot een afname van meer dan 10% van het uitgangsgewicht. Als er na 12 weken behandeling in de onderhoudsdosering geen 5% gewichtsverlies is opgetreden wordt aanbevolen de behandeling stop te zetten. Het is voor liraglutide niet duidelijk wat de effecten zijn na de periode van het eerste jaar. Voor liraglutide zijn in een lagere dosis wel lange termijn data (3 jaar) beschikbaar bij patiënten met prediabtes, waaruit blijkt dat behaald gewichtsverlies met de daar gebruikte dosis behouden blijft. In de studies met betrekking tot liraglutide blijkt het gewichtsverlies vooral in het eerste half jaar plaats te vinden, daarna is er gemiddeld weer geringe gewichtstoename te zien. Ook bij semaglutide blijkt het gewichtsverlies vooral in het eerste half jaar plaats te vinden, bij gebruik tot 68 weken neemt het gewicht nog iets verder af.

Wat betreft comorbiditeiten laten de orlistat, liraglutide, semaglutide en naltrexon/buproprion verschillende effecten zien, maar deze verschillen zijn klein. In de praktijk kan een keuze gemaakt worden op basis van comorbiditeit, zoals een GLP1-analoog bij mensen met Diabetes Mellitus type 2 (voor de behandeling van Diabetes Mellitus type 2 zijn verschillende GLP1-analogen geregistreerd). Met betrekking tot naltrexon/bupropion is er nog weinig ervaring bij mensen met andere psychiatrische problemen, dus het gebruik in deze groep kan risicovol zijn. Bupropion moet worden vermeden bij tachycardie en/of Brugada syndroom omdat het kan leiden tot een afwijkend ECG, bij een verhoogd risico op convulsies en bij ernstige levercirrose. Naltrexon/bupropion kan bloeddrukverhogend werken en is daarom gecontraïndiceerd bij ongecontroleerdev hypertensie. Naltrexon/bupropion kent verschillende interacties. Gelijktijdige toediening van MAO-remmers is gecontraïndiceerd Het gaat het analgetische effect van opioïden tegen. Naltrexon/bupropion is daarom niet geschikt voor mensen die opioïden gebruiken. De blootstelling aan geneesmiddelen die worden gemetaboliseerd door CYP2D6 kan toenemen. Wees voorzichtig bij gelijktijdig gebruik van geneesmiddelen die CYP2D6 induceren en/of bij gelijktijdig gebruik van geneesmiddelen die CYP2D6 kunnen remmen. Met orlistat is voorzichtigheid geboden bij mensen met volume depletie en het wordt afgeraden bij chronisch malabsorptiesyndroom en cholestase. Orlistat vermindert de absorptie van thyreomimetica.

Overige

Een middel is niet meegenomen in de analyse, maar dient wel vermeld te worden. Metformine is geassocieerd met gewichtsverlies, maar dan vooral bij patiënten met diabetes of pre-diabetes. Een systemische review toonde aan dat metformine in de meeste studies leidde tot een significantie gewichtsreductie ten opzichte van placebo. Deze afname was in de meeste gevallen minder dan gezien bij liraglutide en naltrexon/bupropion. Een bijkomend voordeel van metformine bij patiënten met pre-diabetes is dat het beschermt tegen progressie naar Diabetes Mellitus type 2. Hoewel metformine niet geregistreerd is voor gebruik als middel tegen obesitas valt het te overwegen om te gebruiken bij patiënten met een vorm van insulineresistentie/pre-diabetes. Ook bij PCOS zijn gunstige effecten beschreven (maar dit valt buiten deze richtlijn).

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Liraglutide en semaglutide veroorzaken bij meer dan 10% misselijkheid en diarree, maar dat neemt af binnen enkele dagen of weken. Verder is pancreatitis gemeld als ernstige zeldzame bijwerking. Ook Naltrexon/bupropion veroorzaakt bij meer dan 10% van de mensen maagdarm klachten. Daarnaast kan het tot klachten leiden als slapeloosheid, angst en nervositeit. Als ernstige zeldzame bijwerking zijn convulsies gemeld bij bupropion. Orlistat geeft ook bij meer dan 10% van de mensen maagdarmstoornissen, waaronder olieachtige spotting uit het rectum. Ernstige hepatitis is gemeld als ernstige zeldzame bijwerking.

Bupropion kan leiden tot (toename van) slapeloosheid. Om deze reden wordt bij andere indicaties aangeraden het in de ochtend in te nemen. Naltrexon/bupropion dient echter tweemaal daags ingenomen te worden. Ook liraglutide kan slapeloosheid veroorzaken, maar dit is vooral tijdens de eerste 3 maanden van de behandeling.

Alleen van liraglutide en semaglutide is er enig bewijs dat de kwaliteit van leven beter is in combinatie met een GLI, vergeleken met alleen een GLI.

Liraglutide en semaglutide worden subcutaan toegediend, terwijl naltrexon/bupropion en orlistat oraal worden ingenomen.

Tot slot is de richtlijncommissie zich er terdege van bewust dat voorschrijven van medicatie bij de behandeling van obesitas genuanceerd ligt. Enerzijds zal de voorschrijver moeten overwegen dat uit de beschikbare onderzoeken blijkt dat toevoeging van medicatie aan een GLI toegevoegde waarde kan hebben in de behandeling van obesitas. Anderzijds is het niet wenselijk dat medicatie ingezet wordt als ‘monotherapie’ bij de behandeling van obesitas. Dit vraagt om een weloverwogen professionele overweging ten aanzien van de meerwaarde van toevoeging van gewichtsreducerende medicatie in de totale behandeling van obesitas.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Met betrekking tot de kosten van de verschillende medicatie is er een duidelijk verschil waarneembaar. In de standaarddoseringen bij deze indicatie ligt de inkoopprijs (februari 2021) exclusief btw van liraglutide rond de 7 euro per dag, van naltrexon/bupropion rond de 3,50 euro per dag en van de Orlistat rond de 2 euro per dag. Van de semaglutide zijn de kosten nog niet bekend. De daadwerkelijke kosten zullen afwijken vanwege de bijkomende kosten met betrekking tot de btw en een aflevertarief. Bij de behandeling van obesitas met liraglutide of semaglutide bij mensen met diabetes, zullen de middelen zowel helpen voor gewichtsverlies als voor de behandeling van de diabetes. Hierdoor kan de behandeling van de diabetes goedkoper uitkomen.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Het effect van medicatie als aanvulling op GLI is onder andere afhankelijk van therapietrouw. In studies met betrekking tot liraglutide wordt een correlatie waargenomen tussen adherence aan het aantal geplande contactmomenten met de begeleiding van een GLI en het behaalde gewichtsverlies. Dit pleit ervoor om de behandeling niet te starten of voort te zetten als er geen begeleide GLI gevolgd kan worden. Bij mensen bij wie de leefstijl al zodanig is dat er geen verbetering meer te verwachten is met een GLI, kan ook zonder GLI gewichtsreducerende medicatie overwogen worden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Overweeg toevoegen van medicatie aan een GLI bij mensen met obesitas of ernstig overgewicht in combinatie met een vergrote buikomvang en/of comorbiditeit. Orlistat, liraglutide, semaglutide en naltrexon/bupropion helpen, wanneer gecombineerd met een GLI, om meer gewicht te verliezen en het is waarschijnlijk goed mogelijk om na relatief korte tijd te beoordelen of de middelen effectief zijn. Voor orlistat, liraglutide en naltrexon/bupropion geldt dat gestopt dient te worden met deze gewichtsreducerende medicatie als het gewichtsverlies na 12 weken gebruik van de maximaal verdraagbare dosis kleiner is dan 5%. Indien er minder dan 5% gewichtsafname is bereikt maar wel duidelijke verbeteringen zijn opgetreden in de lichaamssamenstelling (afname vetmassa en toename spiermassa) en (bijvoorbeeld cardiometabole) comorbiditeiten, overweeg om de proefperiode met medicatie enkele maanden te verlengen.

Maak een keuze op basis van effectiviteit, prijs en comorbiditeit.

Semaglutide, liraglutide en naltrexon/bupropion zijn effectiever dan Orlistat. In de geïncludeerde studies staan geen vergelijkende onderzoeken tussen liraglutide en semaglutide. Uit onderzoek ten opzichte van placebo lijkt semaglutide effectiever dan liraglutide. Met betrekking tot prijs per dagelijks aanbevolen dosis zijn de bedragen hoog en de verschillen groot. Er zijn voor liraglutide, naltrexon/bupropion en orlistat geen gegevens over gebruik gedurende meer dan 1 jaar bij deze indicatie, maar bij patiënten met prediabetes lijkt het gewichtsverlies met liraglutide gedurende een langere periode te blijven. Voor semaglutide is de werking gedurende 68 weken aangetoond. Op dit moment is er nog te weinig literatuur beschikbaar om op te maken in welke situaties deze middelen het beste ingezet zouden kunnen worden. Wel kan een keuze gemaakt worden op basis van contra-indicaties. Vooral bij een risico op convulsies en bij psychiatrische of verslavingsproblematiek lijkt naltrexon/bupropion geen goede keuze.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Er zijn in Nederland vermoedelijk heel wat mensen die in aanmerking kunnen komen voor gewichtsreducerende medicatie, omdat leefstijlaanpassingen bij hen onvoldoende effect hebben. Velen zullen voor aanvullende behandelingen in aanmerking komen, zoals farmacotherapie of metabole chirurgie. Desondanks wordt deze medicatie maar zeer beperkt voorgeschreven. Er is onduidelijkheid over welke patiënten het meest gebaat zijn bij medicatie, wat het beste moment is om te starten, kosteneffectiviteit en lange termijneffecten.

Introduction

There are probably quite a few people in the Netherlands who would qualify for weight-reducing medication, because lifestyle changes have insufficient effect on them. Many patients are eligible for additional treatments, such as pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery. Nevertheless, this medication is only prescribed to a very limited extent. There is uncertainty about which patients would benefit from weight-reducing medication, the best time to start medication use, cost-effectiveness, and long-term effects.

Conclusies

|

Moderate GRADE |

Weight loss

It is likely that liraglutide, orlistat, and naltrexon-bupropion result in larger weight loss at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Singh, 2020; Khera, 2016, Chao, 2019; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

It is likely that semaglutide results in a larger weight loss at 68 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

It is likely that liraglutide, orlistat and naltrexon-bupropion may result in larger reduction in waist circumference at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Khera, 2018 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

It is likely that semaglutide results in a larger reduction in waist circumference at 68 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021 |

|

Very Low GRADE |

Health-related quality of life

It is unclear what the effect is of liraglutide on health-related quality of life at 52 weeks of follow-up compared to intensive behavioural therapy alone, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Chao, 2019 |

|

Very low GRADE |

Weight-related quality of life

It is unclear what the effect is of liraglutide on improving weight-related quality of life at 52 weeks of follow-up compared to intensive behavioural therapy alone, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Chao, 2019 |

|

low GRADE |

Semaglutide may improve weight-related quality of life at 68 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Davies, 2021 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Comorbidities

Liraglutide and orlistat result in a larger reduction of glucose at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Liraglutide may result in a larger reduction of Hb1Ac at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Semaglutide likely reduces glucose and Hb1Ac at 68 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021 |

|

Low GRADE |

Semaglutide may result in a larger reduction of Hb1Ac at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight.

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Orlistat may result in a larger reduction of LDL-cholesterol at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Semaglutide may result in a larger reduction of LDL-cholesterol at 68 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

It is likely that naltrexon-bupropion results in larger increase of HDL-cholesterol at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

Orlistat and liraglutide may result in a larger reduction of systolic blood pressure at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Low GRADE |

It is likely that orlistat and liraglutide may result in a larger reduction of diastolic blood pressure at 52 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Khera, 2018; Wadden, 2020 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

It is likely that semaglutide may result in a larger reduction of systolic and diastolic blood pressure at 68 weeks follow-up compared to placebo, in adults with obesity or overweight

Sources: Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Khera (2016) compares weight loss among drug treatments for obesity and covers literature until March 2016. Khera (2016) includes 28 RCTs comparing orlistat (16 trials), lorcaserin (3 trials), naltrexon-bupropion (4 trials), phentermine-topiramate (2 trials), liraglutide (2 trial) against placebo. One three-group trial was included comparing liraglutide and orlistat against placebo. The study size of the included trials varied from 220 to 3.731 participants. The outcomes were the proportion of participants achieving at least 5% weight loss from baseline, and the proportion of participants with at least 10% weight loss and change in weight from baseline. The median of the average age of study participants was 45,9 years (range of average age, 40.0–59.8 years) and 74% of participants were women (range, 45%–92%). The median of average body mass index (BMI) of patients was 36.1 kg/m2 (range, 32.6–42.0) and the median of average baseline weight was 100.5kg (range, 95.3–115.8kg). The risk of bias of individual studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool. Overall, studies were considered to be at high risk of bias, with attrition rates of 30% to 45% in all trials (see Figure 2; Khera, 2016). This literature analysis only focuses on the effect of orlistat, naltrexon- bupropion, and liraglutide as drug treatment for obesity, since use of phentermine-topiramate and lorcaserin is not approved in the Netherlands. Specific baseline characteristics for these trials are included in the evidence table.

Singh (2020) compares weight loss among drug treatments for obesity using a and covers literature until September 2019. Singh (2020) includes 31 RCTs comparing orlistat (17 trials), lorcaserin (4 trials), naltrexon-bupropion (4 trials), phentermine-topiramate (2 trials), liraglutide (4 trial) against placebo. The study size of the included trials varied from 45 to 12,000 participants. The outcome was a reduction in body weight (in kilograms) compared to a placebo at the end of 1-year follow-up. The risk of bias in individual studies was assessed in the context of the outcome using the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool on seven domains that include – random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. Overall, studies were considered to be at high risk of bias, due to incomplete data as a result of attrition bias (see Table S1; Singh, 2020). Specific baseline characteristics for orlistat, naltrexon-bupropion, and liraglutide are included in the evidence table.

Khera (2018) compares the effect of weight loss medication on cardiovascular risk profiles in adults with obesity using a systematic review and network meta-analysis and covers literature until February 2017. Khera (2018) includes 28 RCTs comparing orlistat (16 trials), lorcaserin (3 trials), naltrexon-bupropion (4 trials), phentermine-topiramate (2 trials), liraglutide (2 trials) against placebo. One three-group trial was included comparing liraglutide and orlistat against placebo. The study size of the included trials varies from 220 to 3.731 participants. Outcomes were assessed at one year of follow-up. The outcomes were defined a priori and included: glucose profile – fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) and/or HbA1c; markers of lipoprotein metabolism – low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol (mg/dL), high-density lipoprotein(HDL)-cholesterol (mg/dL); systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mmHg); and central adiposity, assessed using waist circumference (cm). The median age of study participants across studies was 46 years (range 41–60) and 77% (range 45–90) were women. The median baseline BMI was 36.1 kg/m2 (range 32.7–42.0). The baseline median fasting blood glucose was 105,6 mg/dL (interquartile range [IQR, 94.6–161.5) and hemoglobin A1c was 7,9% (IQR, 5.7–8.1). The median baseline LDL-cholesterol was 122.7mg/dL (IQR, 112.9–137.2) and HDL-cholesterol was 46.4mg/dL (IQR, 45.5–51.3); median 34.5% (IQR, 10.3–52.5) participants had dyslipidemia. Median average systolic blood pressure was 127.5mmHg (IQR, 121.9–135.8) and diastolic blood pressure was 79.1mmHg (IQR, 77.5–84.2) at baseline; median 23% (IQR, 17–36) participants had hypertension at baseline. Waist circumference was 110cm (IQR, 109–115) at baseline. The risk of bias of individual studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool. Overall, studies were considered to be at high risk of bias, with attrition rates of 30% to 45% in all trials (See table 8; Khera, 2018). Specific baseline characteristics for orlistat, naltrexon-bupropion and liraglutide are included in the evidence table.

Chao (2019) conducted a single-site, open-label, parallel-group design RCT on the effect of liraglutide combined with intensive behavioural therapy (IBT) on weight loss and quality of life compared to a multicomponent group and a IBT alone group (IBT combined with placebo). The RCT by Chao (2019) is of moderate quality (see table of quality assessment) and was commercially sponsored by Novo Nordisk. Chao (2019) included adults aged 21-70 years; body mass index (BMI) of 30-55 kg/m2; and prior lifetime weight-loss effort with diet and exercise (n=150). All participants received 21 sessions of IBT and were instructed to engage in low-to-moderate intensity physical activity 5 days per week, gradually. Participants who weighed <113.6 kg were prescribed a diet of 1200- 1499 kcal/day, while those ≥113.6 kg received 1500-1800 kcal/day. Outcomes include weight loss, health-related quality of life, and weight-related quality of life. The 150 participants included 67 (44.7%) individuals who identified as black and 119 (79.3%) women. The total sample had a mean age of 47.6 (SD=11.8) years, a weight of 108.4 (SD=17.5) kg, and a BMI of 38.4 kg/m2 (SD=4.9). Baseline scores did not differ significantly among treatment groups. At baseline, 28% of the sample had class I obesity, 36.0% had class II and 36% had class III.

Wadden (2020) conducted a 56-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two-armed, multicenter phase 3b trial. The primary objective of the trial was to compare the effect of liraglutide 3.0 mg versus placebo, as an adjunct to standard-based IBT, on weight loss in individuals with obesity. The RCT by Wadden (2020) is of moderate quality (see table of quality assessment) and was commercially sponsored by Novo Nordisk. Wadden (2020) included adults aged ≥ 18 years, with stable body weight and BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (n=282). Participants were randomized to treatment with liraglutide combined with IBT (liraglutide-IBT; n=142) or a placebo combined with IBT (placebo-IBT; n=140). The primary outcomes were change in body weight (percent) from baseline to week 56 and the proportion of participants who lost ≥ 5% of baseline body weight. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of participants who lost > 10% or > 15% of baseline body weight at week 56. Of the 142 participants included in the liraglutide-IBT arm 78.9% of individuals were identified as white and 16.2% were male. The liraglutide-IBT arm had a mean age of 45.4 (SD=11.6) years, the weight of 108.5 kg (SD=22.1), and a BMI of 39.3 kg/m2 (SD=6.8). Of the 140 participants included in the placebo-IBT arm 82.1% of individuals were identified as white and 17.1% were male. The placebo-IBT arm had a mean age of 49.0 (SD=11.2) years, the weight of 106.7 kg (SD=22.0), and a BMI of 38.7 kg/m2 (SD=7.2). Baseline scores did not differ significantly among treatment groups.

Semaglutide vs placebo

Zhong (2022) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide among adults with overweight or obesity. Zhong (2022) covers the literature until July 2021. Literature searches were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Zhong (2022) included randomized controlled trials which enrolled adults (≥18 years old) with a body-mass index of 27 kg/m2 or higher and without diabetes and compared once-weekly semaglutide and placebo. In total, 4 studies were included. All included studies were randomized double-blind trials that compared the treatment effect of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg with placebo in patients with overweight or obesity. Article quality of individual studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool. The primary outcomes were the percentage change and absolute change in body weight from baseline. Secondary outcomes included achievement of categorical weight loss targets (at least 5, 10, 15, or 20%) and change from baseline in waist circumference, body-mass index, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), systolic and diastolic blood pressure, physical functioning score on the 36-item Short-form Health Survey (SF-36), the SF-36 physical and mental component summary scores, and lipid profiles (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglycerides).

Davies (2021) conducted an double-blind, double-dummy, phase 3, superiority study evaluating the efficacy and safety of once a week subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg versus semaglutide 1.0 mg (the dose approved for diabetes treatment) and placebo for bodyweight management in adults with overweight or obesity. Included were adults (≥18 years old) with a body-mass index of 27 kg/m2 or higher that reported at least one unsuccessful dietary effort to lose weight and who were diagnosed with diabetes at least 180 days before screening. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to semaglutide 2.4 mg, semaglutide 1.0 mg, or placebo. In total, 404 patients were allocated to the semaglutide 2.4 mg group (mean age 55 ± 11 years; mean BMI 35.9 ± 6.4 kg/m2; 55.2% female), 403 were allocated to the semaglutide 1.0 mg group (mean age 56 ± 10 years; mean BMI 35.3 ± 5.9 kg/m2; 50.4% female) and 403 were allocated to the placebo group (mean age 55 ± 11.0 years; mean BMI 35.3 ± 6.4 kg/m2; 47.1% female). Patients received semaglutide 2.4 mg or semaglutide 1.0 mg or placebo once a week for 68 weeks, plus a lifestyle intervention, followed by 7 weeks without treatment. Semaglutide was started at 0,25 mg per week and escalated in a fixed-dose regimen every 4 weeks until the target dose was reached. The lifestyle intervention involved counselling on diet (500 kcal per day reduction relative to the estimated total daily energy expenditure calculated at time of random allocation) and physical activity (150 min per week). Outcomes (semaglutide 2.4 mg vs placebo), were percentage change in bodyweight from baseline to week 68 and loss of at least 5% of baseline weight at week 68 (semaglutide 2,4 mg vs placebo), proportions of patients achieving bodyweight reductions of at least 10% or 15% at week 68, change from baseline to week 68 in waist circumference, change from baseline to week 68 in HbA1c, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, SF-36v2 physical functioning score, and IWQOL-Lite-CT physical function score.

Results

Weight loss

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

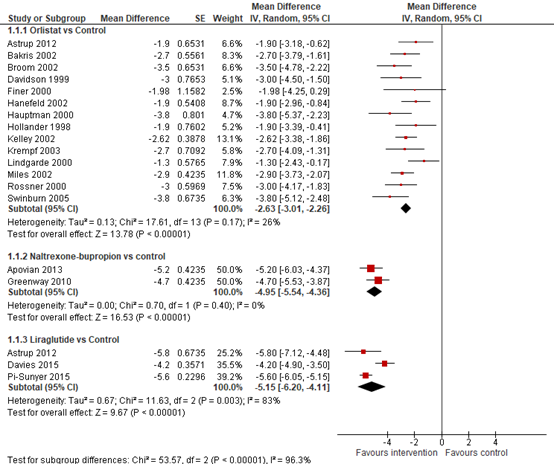

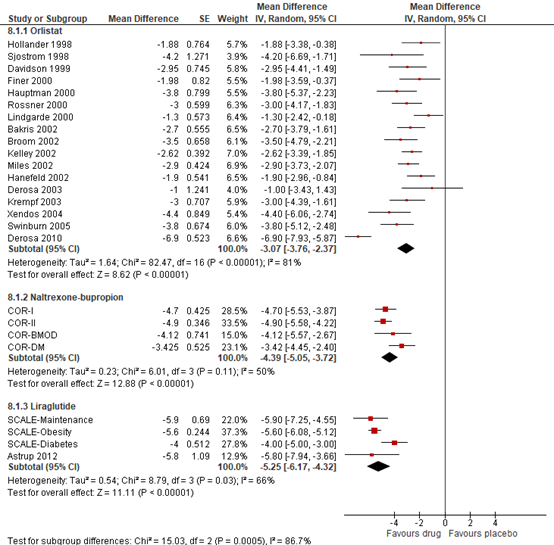

In the direct pairwise meta-analysis by Khera (2016), weight loss compared with placebo at one year (52+4weeks) resulted in a mean difference (MD) of MD=2.6 kg (95% CI 2.3 to 2.9) with orlistat, MD=5.0 kg (95% CI 4.4 to 5.5 kg) with naltrexon-bupropion, and MD=5.2kg (95% CI 4.9 to 5.6) with liraglutide (see Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Forrest plot showing the effect of orlistat, naltrexon-bupropion, and liraglutide on weight in comparison to placebo. Mean differences, random-effects model (Khera, 2016).

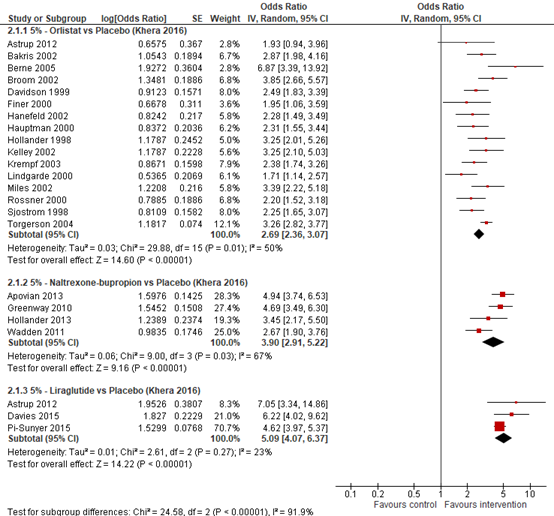

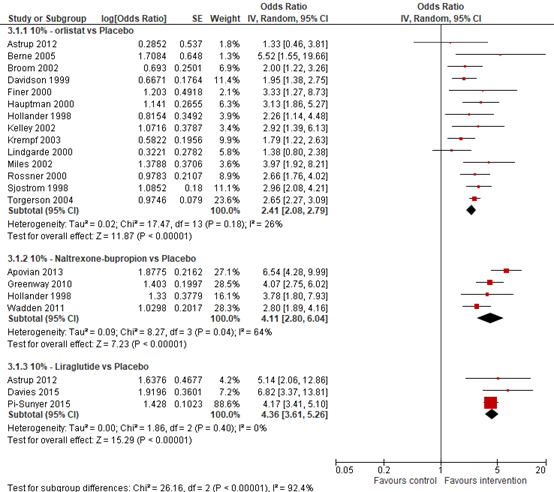

In a direct meta-analysis by Khera (2016), all agents were associated with higher odds of achieving clinically relevant weight loss. Odds of achieving 5% weight loss from baseline compared with placebo at one year (52+4weeks) were OR=2.69 (95% CI 2.31to 3.12) for orlistat, OR=3.90 (95% CI 2.43 to 6.26) for naltrexon-bupropion, and OR=5.19 (95% CI 2.95 to 9.15) for liraglutide (See Figure 8.2). All agents were also associated with higher odds of at least 10% weight loss from baseline compared with placebo at one year (52+4weeks) with OR=2.41 (95% CI 2.05 to 2.83) for orlistat, OR=4.11 (95% CI 2.22 to 7.63) for naltrexon-bupropion, and OR=4.57 (95% CI 2.43 to 8.58) for liraglutide (See Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.2 Forrest plot showing the odds of patients achieving 5% weight loss using orlistat, naltrexon and liraglutide in comparison to placebo. Odds ratio, random effects model (Khera, 2016).

Figure 8.3. Forrest plot showing the odds of patients achieving 10% weight loss using naltrexon-bupropion in comparison to placebo. Odds ratio, random effects model (Khera, 2016).

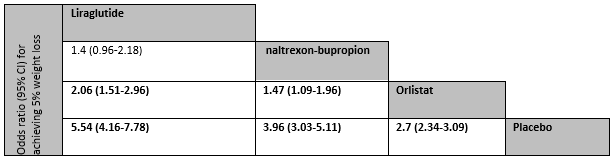

Network meta-analysis demonstrated that significantly more patients treated with liraglutide (OR=2.06; 95% CI 1.51 to 2.96) and naltrexon-bupropion (OR=1.47; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.96) had achieved at least 5% weight loss compared. More patients treated with liraglutide also achieved 5% weight loss compared to naltrexon-bupropion (OR=1.4; 95% CI 0.96 to 2.18), but this difference was not statistically significant (Figure 8.4)

Fig 8.4. Comparing the proportion achieving 5% weight loss in network meta-analysis. Odds ratios for comparisons are in the cell in common between the column-defining and row-defining treatment. (Khera, 2016)

In the meta-analysis by Singh (2020) significant reduction in body weight compared to baseline was observed for orlistat (mean difference, MD=−3.07Kg; 95% CI −3.76 to −2.37), naltrexon-bupropion (MD=−4.39Kg; 95% CI −5.05 to −3.72) and liraglutide (MD=−5.25Kg; 95% CI −6.17 to −4.32), compared to placebo (See Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5 Forrest plot showing the effect of orlistat, naltrexon-bupropion, and liraglutide on weight in comparison to placebo. Mean differences, random-effects model (Singh, 2020).

Chao (2019) reported that weight loss in the IBT liraglutide (11.5%; SD=1.3%; P=0.005) and multicomponent (11.8%; SD=1.3%; P=0.003) groups were significantly greater compared to IBT alone (6.1; SD=1.3%). At week 52, 44% of participants in IBT-alone, 70% in IBT-liraglutide and 74% in multicomponent achieved clinically relevant weight loss of ≥5% of initial weight; 26%, 46%, and 52% of these participants, respectively, lost ≥10% of initial weight.

Wadden (2020) estimated mean weight change at week 56 was −7.5% for liraglutide-IBT and −4.0% for placebo-IBT. The estimated mean difference (MD) between groups was MD=−3.4%; (95% CI −5.3% to −1.6%). A higher proportion of 61.5% of participants achieved clinically relevant weight loss of ≥ 5% at 56 weeks with liraglutide-IBT compared to 38.8% of participants with placebo-IBT (OR 2.5%; 95% CI 1.5% to 4.1%). The proportions who lost > 10% were 30.5% (liraglutide-IBT) and 19.8% (placebo-IBT), and the proportions who lost > 15% were 18.1% (liraglutide-IBT) and 8.9% (placebo-IBT).

Semaglutide vs placebo

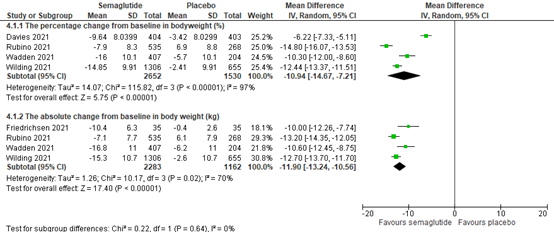

Two studies reported on the effect of 2.4 mg semaglutide on the percentage change from baseline in bodyweight compared to placebo (Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021). One study was published after the systematic review by Zhong (2022) and was used to update the meta-analysis.

Zhong (2022) included 3 RCTs (3375 patients) comparing 2.4 mg semaglutide with placebo that reported on the percentage change from baseline in bodyweight. The pooled mean difference (MD) was -12.57% (95% CI -14.80 to -10.35; Figure 6) in favour of semaglutide. In addition, Zhong included 4 RCTs (3345 patients) comparing 2.4 mg semaglutide with placebo that reported on the absolute change from baseline in bodyweight. The pooled mean difference (MD) was -11.90% (95% CI -13.24 to -10.56; Figure 6) in favour of semaglutide

Davies (2021) found an mean weight loss of -9.64% + 8.04% in the semaglutide group compared to -3.42% + 8.03% in the placebo group. The MD was -6.22% (95% -7.33 to -5.11; Figure 8.6).

In summary, there were 4 RCTs (4252 patients) comparing 2.4 mg semaglutide with placebo that reported the percentage change from baseline in bodyweight. The pooled MD was -10.94% (95% CI -14.67 to -7.21; Figure 6) in favour of semaglutide. This is a clinically relevant difference. 4 RCTs (3345 patients) reported absolute change from baseline in bodyweight.

Figure 8.6 Forrest plot showing the effect of semaglutide on absolute weight change from baseline in comparison to placebo. Mean differences, random-effects model.

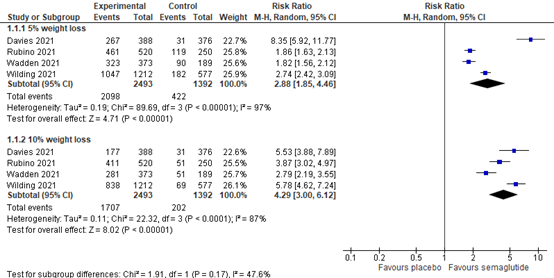

In addition, two studies reported on the effect of 2.4 mg semaglutide on achieving clinically relevant weight loss of 5% and 10% from baseline compared to placebo (Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021). One study was published after the systematic review by Zhong (2022) and was used to update the meta-analysis.

Zhong (2022) included 3 RCTs (3121 patients) and found that semaglutide was associated with achieving clinically relevant weight loss of 5% (RR=2.11; 95% CI 1.59 to 2.78) and 10% (RR=3.98; 95% CI 2.58 to 6.13) from baseline compared with placebo (See Figure 7).

Davies (2021) found that semaglutide was associated with achieving clinically relevant weight loss of 5% (RR=8.35; 95% CI 5.92 to 11.77) and 10% (RR=5.53; 95% CI 3.88 to 7.89; figure 7) from baseline compared to placebo.

In summary, there were 4 RCTs (3885 patients) that reported achieving 5% and 10% weight loss compared to baseline. They found 2098/2493 events in the semaglutide group compared to 422/1392 in the placebo group of patients achieving 5% weight loss. The RR was 2.88 (95% CI 1.85 to 4.46; Figure 7) in favour of semaglutide. Moreover, they found 1707/2493 events in the semaglutide group and 202/1392 in the placebo group of patients achieving 10% weigh loss. The RR was 4.29 (95% CI 3.00 to 6.12; Figure 8.7) in favour of semaglutide.

Figure 8.7 Forrest plot showing the effect semaglutide on achieving 5% and 10% weight loss from baseline in comparison to placebo. Risk Ratio, random-effects model.

Quality of life

Health-related quality of life

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Chao (2019) used the SF-36 short form health survey to assess health-related quality of life in participants treated with IBT combined with liraglutide (IBT-liraglutide), multicomponent IBT combined with liraglutide (multicomponent) and IBT combined with placebo (IBT-alone). The SF-36 scale creates two summary measures: (1) a physical component summary and (2) a mental component summary, as well as eight subscales. Scores are transformed using a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better health related quality of life. Changes from baseline ≥3.8 points on the SF-36 physical component summary score or ≥4.6 points on the SF-36 mental component summary score are considered clinically relevant. From baseline to week 50, compared to IBT-alone, IBT-liraglutide had significantly greater improvements in bodily pain and mental health, while multicomponent had significantly greater improvements in mental component summary, bodily pain, social functioning, role emotion and mental health (see table 8.1). At week 52, 50% of participants in IBT-alone, 34% in IBT-liraglutide and 48% in multicomponent had clinically relevant improvements in the PCS score; 32%, 42% and 44% of these participants, respectively, reported clinically relevant improvements on the mental components summary score. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in the percent of participants with clinically relevant improvements in physical- or mental component scores.

Table 8.1 Estimated mean (±SE) changes in health-related quality of life at 52 weeks, as measured from randomization, in the intention-to-treat population (N = 150)

|

|

|

|

|

P-value |

|

|

|

IBT-alone (N=50) |

IBT+liraglutide (N=50) |

Multicomponent N=50) |

IBT-liraglutide vs IBT alone |

Multicomp. Vs IBT alone |

|

Physical component summary |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+4.4 (SE=1.0) |

+2.1 (SE=1.0) |

+3.4 (SE=1.0) |

0.11 |

0.41 |

|

Mental component summary |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+0.8 (SE=1.3) |

+4.5 (SE=1.3) |

+6.4 (SE=1.3) |

0.48 |

0.003 |

|

Physical functioning |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+8.2 (SE=2.9) |

+10.3 (SE=2.9) |

+7.9 (SE=3.0) |

0.60 |

0.95 |

|

Role physical |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+5.8 (SE=4.7) |

+6.8 (SE=4.6) |

+16.0 (SE=4.7) |

0.88 |

0.12 |

|

Bodily pain |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+11.1 (SE=2.9) |

−1.2 (SE=2.9) |

+4.0 (SE=2.9) |

0.003 |

0.09 |

|

General health |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+5.4 (SE=2.2) |

+10.1 (SE=2.2) |

+8.8 (SE=2.2) |

0.13 |

0.28 |

|

Vitality |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+14.2 (SE=2.9) |

+11.0 (SE=2.8) |

+15.6 (SE=2.8) |

0.43 |

0.71 |

|

Social functioning |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+5.2 (SE=3.5) |

+6.8 (SE=3.4) |

+17.4 (SE=3.4) |

0.75 |

0.01 |

|

Role emotion |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

−0.9 (SE=4.9) |

+9.3 (SE=4.9) |

+16.2 (SE=4.9) |

0.14 |

0.01 |

|

Mental health |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+0.9 (SE=2.6) |

+9.6 (SE=2.6) |

+8.0 (SE=2.6) |

0.02 |

0.05 |

Values shown are means (±SE). For each variable, the three treatment groups were compared using pair-wise comparisons. Abbreviations: IBT, intensive behavioural therapy.

Weight-related quality of life

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Chao (2019) used the 31-item impact of weight quality of life-Lite scale to assess weight-related quality of life among participants in the IBT-liraglutide, multicomponent, and IBT-alone arms. Scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the worst quality of life and 100 representing the best. A change of 7.7 to 12 points on the total score represents a clinically relevant change. From baseline to week 52, compared to IBT-alone, IBT-liraglutide significantly had significantly greater improvements in public distress, while multicomponent had significantly greater improvements in total score, and public distress (see Table 2). At week 52, 44.4% of IBT-alone, 64.4% of IBT-liraglutide, and 65.2% of multicomponent participants achieved clinically relevant improvements in weight-related quality of life (as measured by the total score). After covariate adjustment, compared to participants in IBT-alone, the odds of achieving clinically relevant improvements in total weight-related quality of life were significantly greater for individuals in IBT-liraglutide (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 2.4; 95% CI 1.02 to 5.8; P = 0.046) and in multicomponent (adjusted OR = 2.4; 95% CI 1.01 to 5.6; P = 0.047).

Table 8.9 Estimated mean (±SE) changes in weight-related quality of life at 52 weeks, as measured from randomization, in the intention-to-treat population (N = 150)

|

|

|

|

|

P-value |

|

|

|

IBT-alone (N=50) |

IBT+liraglutide (N=50) |

Multicomponent N=50) |

IBT-liraglutide vs IBT alone |

Multicomp. Vs IBT alone |

|

Total score |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+12.3 (SE=2.1) |

+15.8 (SE=2.1) |

+19.4 (SE=2.1) |

0.24 |

0.02 |

|

Physical function |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+14.4 (SE=2.5) |

+17.4 (SE=2.5) |

+18.6 (SE=2.5) |

0.40 |

0.24 |

|

Self-esteem |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+16.1 (SE=3.4) |

+22.0 (SE=3.4) |

+25.4 (SE=3.4) |

0.22 |

0.05 |

|

Sexual life |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+14.1 (SE=3.3) |

+12.0 (SE=3.3) |

+22.1 (SE=3.3) |

0.65 |

0.09 |

|

Public distress |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+3.2 (SE=2.7) |

+10.9 (SE=2.7) |

+14.8 (SE=2.7) |

0.04 |

0.03 |

|

Work |

|||||

|

Week 52 |

+9.7 (SE=2.5) |

+9.3 (SE=2.5) |

+14.5 (SE=2.5) |

0.91 |

0.18 |

Values shown are means (±SE). For each variable, the three treatment groups were compared using pair-wise comparisons. Abbreviations: IBT, intensive behavioural therapy.

Semaglutide vs placebo

Davies (2021) used the 31-item impact of weight quality of life-Lite scale to assess weight-related quality of life among participants in the semaglutide 2.4 mg and placebo group. Scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 representing the worst quality of life and 100 representing the best quality of life. They found that the semaglutide group showed a change from baseline to week 68 of 10.1 + 19.7 compared to 5.3 + 21.3 for the placebo group. The MD was 4.80 (95% CI 1.89 to 7.71) in favour of the semaglutide group, but this difference was not clinically relevant.

Comorbidities

Effects on blood glucose profile

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Using meta-analysis to compare different agents to placebo, Khera (2018) found that liraglutide was associated with a moderate reduction in fasting blood glucose compared to placebo (mean difference, MD=-15.6mg/dL; 95% CI −23.7 to −7.6; SMD=−0.72) followed by orlistat (MD=−8.0mg/dl; 95% CI −12.2 to −3.7; SMD=−0.23). None of these differences were, however, considered clinically relevant. Naltrexon/bupropion was not associated with a significant or clinically relevant decline in fasting blood glucose compared to placebo (MD=-2.8 mg/dL; 95% CI -10.1 to 4.4; SMD=-0.13).

Khera (2018) observed moderate reduction for HbA1c with liraglutide compared to placebo (MD=−0.5%; 95% CI −0.9 to −0.2; SMD, −0.54) followed by orlistat (MD=−0.4%; 95% CI −0.6 to −0.2; SMD, −0.38). Only liraglutide resulted in a clinically relevant decline. Naltrexon/bupropion was not associated with a significant or clinically relevant decline in HbA1c compared to placebo (MD=-0.5%; 95% CI -1.1, 0.1; SMD=-0.33).

Wadden (2020) found a significant but not a clinically relevant difference in reduction of fasting blood glucose between liraglutide-ITD and placebo-ITD at 56 weeks (MD=−0.23 mmol/L; 95% CI −0.36 to −0.11). Wadden (2020) also found a significant and clinically relevant difference in reduction of HbA1c (MD−0.10%; 95% CI −0.2 to −0.04).

Semaglutide vs placebo

Zhong (2022) included 3 RCTs (3375 patients) and found that compared with placebo, once-weekly semaglutide significantly reduced HbA1c (MD –0.25%, 95% CI –0.31 to –0.19), but this was not a clinically relevant difference. Moreover, the reduction of fasting plasma glucose was greater in patients who received once-weekly semaglutide than in patients who received placebo (MD –7.40 mg/dL, 95% CI –8.40 to –6.41), but this was also not a clinically relevant difference.

Davies (2021) found that the semaglutide group showed a change in HbA1c from baseline to week 68 of -1.6% + 1.95% compared to -0.4% + 1.93% for the placebo group. The MD was -1.20 % (95% CI -1.48 to -0.92) in favour of the semaglutide group. This is a clinically relevant difference.

Effects on cholesterol profile

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Using direct meta-analysis to compare different agents to placebo, Khera (2018) found that orlistat was associated with a significant and clinically relevant reduction in LDL-cholesterol compared to placebo (MD=−8.7mg/dl; 95% CI −10.7 to −6.7; SMD=−0.27). Liraglutide (MD=-3.6; 95% CI -7.8 to 0.6; SMD=-0.11) and naltrexon/bupropion (MD= -1.86; 95% CI -4.87 to 1.16; SMD=-0.09) was not associated with a significant or clinically relevant reduction in LDL-cholesterol compared to placebo. For HDL-cholesterol compared to placebo, naltrexon-bupropion (MD=2.5mg/dL; 95% CI 1.2 to 3.8; SMD 0.40) was associated with increase in HDL-cholesterol at 1 year follow-up. In contrast, orlistat was associated with decline in HDL-cholesterol (MD=−1.1mg/dL; 95% CI −1.9 to −0.4; SMD, −0.11) compared to placebo, but this decline was not clinically relevant.

Wadden (2020) found no significant difference in LDL-cholesterol between liraglutide-ITD and placebo-ITD at 56 weeks (MD=−0.07; 95% CI −0.21 to 0.06) and in HDL-cholesterol (MD=0.02; 95% CI −0.02 to 0.07).

Semaglutide vs placebo

Zhong (2022) included 2 RCTs (1414 patients) and found that semaglutide reduced the MD in percentage of total cholesterol by -5.93% (95% CI -4.34 to -7.51) when compared with placebo. In addition, compared with placebo, the reduction in the MD in percentage of LDL was -6.55% (95% CI -4.19 to -8.92), but semaglutide showed a neutral effect on the percentage of HDL with a MD of 0.54% (95% CI -1.46 to 2.53)

Davies (2021) found no significant or clinically relevant difference between the semaglutide and placebo group at 68 weeks to baseline ratio of total cholesterol (MD=0.99; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.02), HDL-cholesterol (MD=1.03; 95% CI 1.00 to 1.05) and in LDL-cholesterol (MD=1.00; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.05).

Effects on blood pressure

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Using direct meta-analysis to compare different agents to placebo, Khera (2018) found that liraglutide (MD= -2.8mmHg; 95% CI −4.3 to −1.2; SMD, −0.24) and orlistat (MD= -1.7mm Hg; 95% CI −2.4 to −0.9; SMD, −0.19) were associated with modest reductions in systolic blood pressure, but these reductions were not considered clinically relevant. No reduction was observed for naltrexon/bupropion (MD=1.1; 95% CI -0.7 to 2.8, SMD=0.05). Similar changes were seen in diastolic blood pressure with modest reductions observed for liraglutide (MD=-0.83; 95% CI -1.7 to 0.0, SMD=-0.08) and orlistat (MD=-1.6; 95% CI -2.0 to -1.1, SMD=-0.71), but these reductions were also not considered clinically relevant. No reduction was observed for naltrexon/bupropion (MD=0.1; 95% CI -0.6 to 0.7; SMD=0.01).

Wadden (2020) found no significant or clinically relevant difference in systolic blood pressure between liraglutide-ITD and placebo-ITD at 56 weeks (MD−2.2; 95% CI −4.9 to 0.5) and in diastolic blood pressure (MD=−0.2; 95% CI −2.12 to 1.8).

Semaglutide vs placebo

Zhong (2022) included 3 RCTs (3375 patients) and found that once-weekly semaglutide resulted in a significant and clinically relevant reduced systolic blood pressure with a MD of -4.62 mm Hg (95% CI -5.57 to -3.66) when compared with placebo, and the decrease of diastolic blood pressure was also more significant but not clinically relevant in the once-weekly semaglutide group with a MD of -1.82 mm Hg (95% CI -2.94 to -0.70) when compared with placebo.

Davies (2021) found that the semaglutide group showed a change in systolic blood pressure from baseline to week 68 of -3.9 mm Hg + 13.8 mm Hg compared to -0.5 mm Hg + 15.5 mm Hg for the placebo group. The MD was -3.40 mm Hg (95% CI -5.48 to -1.32) in favour of the semaglutide group. In addition, diastolic blood pressure showed showed a change in diastolic blood pressure from baseline to week 68 of -1.6 mm Hg + 7.9 mm Hg compared to -0.9 mm Hg + 9.7 mm Hg for the placebo group. The MD was -0.70 mm Hg (95% CI -1.95 to 0.55) in favour of the semaglutide group.

Effects on waist circumference

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Using direct meta-analysis to compare different agents to placebo, Khera (2018) found that all agents were associated with a decrease in waist circumference liraglutide by 4cm (95% CI −5.0, −3.3; SMD=−0.63), naltrexon-bupropion 3.5cm (95% CI −4.4 to −2.6; SMD=−0.37 and orlistat by 2.3cm (95% CI −2.8 to −1.7; SMD=−0.26). Only liraglutide and naltrexon-bupropion were also associated with clinically relevant decrease of at least 3cm.

Wadden (2020) showed that waist circumference decreased significantly more in liraglutide-IBT than in the placebo-IBT participants (MD=−2.7 cm; 95% CI −4.7 to −0.8), but this difference was not considered clinically relevant.

Semaglutide vs placebo

Zhong (2022) included 3 RCTs (3375 patients) and fount that compared with placebo, once-weekly semaglutide was associated with a MD reduction in waist circumference of –9.34 cm (95% CI –10.00 to –8.68).

Davies (2020) found that the semaglutide group showed a change from baseline to week 68 of -9.4 cm + 7.9 cm compared to -4.5 cm + 7.8 cm for the placebo group. The MD was -4.90 cm (95% CI -6.01 to -2.79) in favour of the semaglutide group.

Adverse events

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

Wadden (2020) reported that Liraglutide 3.0 mg combined with IBT was generally well tolerated. The most frequent adverse events were gastrointestinal (71% with liraglutide-IBT vs. 49% with placebo-IBT), The incidence of nausea was greater with liraglutide-IBT (47.9%) than with placebo-IBT (17.9%). Three acute gallstone disease events occurred with liraglutide-IBT and two with placebo-IBT. No events of pancreatitis were observed in the study. The proportion of participants with reported serious adverse events was 4.2% (seven events in six participants) in liraglutide-IBT and 1.4% (two events in two participants) with placebo-IBT. There were no deaths.

Non of de included assessed the association between adverse events and other weight loss medication (orlistat and naltrexon-bupropion) in treating obesity or overweight in adults.

Semaglutide vs placebo.

Zhong (2022) found no significant differences in the risk of hypoglycemic events, acute pancreatitis, acute renal failure, malignant neoplasms, and all-cause death between once-weekly semaglutide and placebo. However, nausea (RR=2.60; 95% CI 2.25 to 2.99), vomiting RR(=3.35; 95% 2.65 to 4.24), diarrhoea (RR=1.92; 95% CI 1.61 to 2.29), and constipation (RR=1.91; 95% CI 1.34 to 2.72) were reported more frequently with once-weekly semaglutide than with placebo.

Davies (2021) found that 353/503 (87.6%) of patients reported adverse events in the semaglutide 2.4 mg group compared to 309/402 (76.9%) patients in the placebo group. The RR was 1.14 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.22) in favour of placebo.

Cost effectiveness

No studies assessed the cost effectiveness of weight loss medication on treating obesity or overweight in adults.

Level of evidence of the literature

Orlistat, liraglutide, naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo

The level of evidence of RCTs comparing orlistat, liraglutide and/or naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo starts high. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure weight loss was downgraded by one level because of study limitations (risk of bias due to high attrition rates for all trials).

The level of evidence regarding quality of life were downgraded to very low because of risk of bias and serious imprecision. There was high risk of bias since blinding of the trials was unclear or not possible and only one study reported on quality of life with large standard errors of effect size (imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure comorbidities was downgraded moderate because of study limitations (risk of bias due to high attrition rates for all trials). It was downgraded to low for HbA1c, LDL-cholesterol and blood pressure outcomes because of conflicting results (inconsistency).

Semaglutide vs Placebo

The level of evidence of RCTs comparing semaglutide vs placebo starts high. The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure weight loss was downgraded by one level to moderate because of inconsistency (due to considerable heterogeneity among the included RCTs, possibly attributable to the variation in sample sizes, baseline characteristics of patient populations, and trial durations).

The level of evidence regarding quality of life was downgraded with two levels to low because of serious imprecision (95% confidence intervals crossing the border for clinical relevance).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure HbA1c, blood pressure, and waist circumference were downgraded to moderate. The level of evidence for the outcome measure HbA1 was downgraded because of conflicting results (inconsistency). The level of evidence for blood pressure and waist circumference was downgraded because the 95% confidence interval crossed the border for clinical relevance (imprecision).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure glucose and cholesterol was downgraded to low because of conflicting results (inconsistency) and the 95% confidence interval crossing the border for clinical relevance, and only one study reporting on the outcome with a low number of events (imprecision).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effect of pharmaceutical treatment combined with behavioural or lifestyle intervention compared to placebo in treating overweight with comorbidities or obesity in adults?

P: Adults with obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and adults with overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) with comorbidities.

I: Weight loss medication (orlistat, naltrexon/bupropion, liraglitude 3 mg, semaglutide).

C: Placebo.

O: Weight loss, maintaining the quality of life, comorbidities (glucose/diabetes), adverse events, cost-effectiveness.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered weight as a crucial outcome measure for decision making; and comorbidities and quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group defined the outcome measure comorbidities as follows: diabetes-related parameters (HbA1c, glucose) and cardiovascular risk factors (HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure)

The working group defined the following outcomes as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference.

- Weight loss: 5% (Khera, 2016).

- Quality of Life: changes from baseline ≥ 3.8 points on the SF-36 physical component summary score or ≥ 4.6 points on the SF-36 mental component summary score (Chao 2019).

- Weight related quality of life: A change of 7.7 to 12 points on the total score (Chao 2019).

- Comorbidities

- Cardiovascular risk factors: SBP: 3 mmHg; DBP: 2 mmHg; LDL: 0.13 mmol/L (5 mg/dL) 5% reduction; and HDL: 0.05 mmol/L (2 mg/dL) or a 5% increase

- Glucose: 1 mmol/L (18 mg/dL).

- HbA1c: 0.5%

- Waist circumference: 3 cm

Search and select (Methods)

Three different literature searches were performed. At first we searched for systematic reviews and after this we performed an additional search to supplement the selected review(s) with RCT’s that were published after the search date of the selected review(s). Finally, during development of this module we learned that semaglutide was approved as weight loss medication for the treatment of obesity and updated our search to include it.

Search 1: Systematic reviews (SR)

- The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 2005 until the 27th of June 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 382 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews (SR) investigating the effect of pharmacological treatments for obesity on weight loss and cardiovascular risk in adults with obesity and overweight compared to adults with obesity and overweight receiving placebo. Fifteen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 12 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and three studies were included (Khera, 2016; Khera, 2018; Singh; 2020).

Search 2: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

- The search strategy of the systematic review (Singh, 2020) was complete up on 30 September 2019. Therefore, we performed an additional search on RCTs in the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) with relevant search terms between 1st of January 2019 until and the 22nd of July 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 184 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: RCTs investigating the effect of pharmacological treatments for obesity on weight loss and cardiovascular risk in adults with obesity and overweight compared to adults with obesity and overweight receiving a placebo. Four studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, two studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included (Chao, 2019; Wadden, 2020).

Search 3: Semaglutide

- The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from the 1st of January 2005 until the 7th of February 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 59 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: SRs and RCTs investigating the effect of semaglutide as treatment for obesity on weight loss and cardiovascular risk in adults with obesity and overweight compared to adults with obesity and overweight receiving placebo. 12 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 10 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 2 studies were included Zhong, 2022; Davies, 2021).

Results

7 studies were included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Acosta, A., Camilleri, M., Abu Dayyeh, B., Calderon, G., Gonzalez, D., McRae, A., & Clark, M. M. (2021). Selection of Antiobesity Medications Based on Phenotypes Enhances Weight Loss: A Pragmatic Trial in an Obesity Clinic. Obesity, 29(4), 662-671.

- Chao, A. M., Wadden, T. A., Walsh, O. A., Gruber, K. A., Alamuddin, N., Berkowitz, R. I., & Tronieri, J. S. (2019). Changes in health?related quality of life with intensive behavioural therapy combined with liraglutide 3.0 mg per day. Clinical Obesity, 9(6), e12340.

- Iepsen, E. W., Zhang, J., Thomsen, H. S., Hansen, E. L., Hollensted, M., Madsbad, S., ... & Torekov, S. S. (2018). Patients with obesity caused by melanocortin-4 receptor mutations can be treated with a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist. Cell metabolism, 28(1), 23-32.

- Khera, R., Murad, M. H., Chandar, A. K., Dulai, P. S., Wang, Z., Prokop, L. J., ... & Singh, S. (2016). Association of pharmacological treatments for obesity with weight loss and adverse events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama, 315(22), 2424-2434.

- Khera, R., Pandey, A., Chandar, A. K., Murad, M. H., Prokop, L. J., Neeland, I. J., ... & Singh, S. (2018). Effects of weight-loss medications on cardiometabolic risk profiles: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gastroenterology, 154(5), 1309-1319.

- Kleinendorst, L., Massink, M. P., Cooiman, M. I., Savas, M., van der Baan-Slootweg, O. H., Roelants, R. J., ... & van Haelst, M. M. (2018). Genetic obesity: next-generation sequencing results of 1230 patients with obesity. Journal of medical genetics, 55(9), 578-586.

- Singh, A. K., & Singh, R. (2020). Pharmacotherapy in obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of anti-obesity drugs. Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology, 13(1), 53-64.

- Wadden, T. A., Tronieri, J. S., Sugimoto, D., Lund, M. T., Auerbach, P., Jensen, C., & Rubino, D. (2020). Liraglutide 3.0 mg and intensive behavioral therapy (IBT) for obesity in primary care: the SCALE IBT randomized controlled trial. Obesity, 28(3), 529-536.

- Welling, M. S., de Groot, C. J., Kleinendorst, L., van der Voorn, B., Burgerhart, J. S., van der Valk, E. S., & van Rossum, E. F. (2021). Effects of Glucagon-Like-Peptide-1 Analogue Treatment in Genetic Obesity. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 5(Supplement_1), A33-A34.

- Wilding, J. P., Batterham, R. L., Calanna, S., Davies, M., Van Gaal, L. F., Lingvay, I., & Kushner, R. F. (2021). Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity. New England Journal of Medicine.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence tables

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What is the effect of pharmaceutical treatment combined with behavioural or lifestyle intervention compared to placebo in treating overweight and comorbidities or obesity in adults?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control ©

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Khera, 2016

|

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to March 2016

Study design: RCT parallel group design (all included RCTs)

Setting and Country: Not reported

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported for the individual studies |

Inclusion criteria SR: Treatment period >1 year; comparison with placebo; obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI ≥27 kg/m2) adults ( ≥18 years)

28 included studies

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See table eTable 1; Khera (2016) for baseline characteristics of the individual RCTs

|

Describe intervention - Orlistat (120 mg 3 times daily) - Naltrexon-bupropion (32 mg/ 360mg twice daily) - Liraglutide (3 mg subcutaneous injection daily)

|

Describe control - Placebo |

End-point of follow-up -52 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) See table eTable 1; Khera (2016) for number of participants with complete outcome data in the intervention and control group.

|

Outcome 5% weight loss Effect medication on achieving 5% weight loss; odds ratio(OR) [95% CI]: See eFigure 3A, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT Pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): OR=2.69; (95% CI=[2.36, 3.07]) favouring orlistat Heterogeneity (I2): 49.7% Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): OR=3.90; (95% CI=[2.91, 5.22]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion Heterogeneity (I2): 66.7%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): OR=5.09; (95% CI=[4.07, 6.37]) favouring liraglutide Heterogeneity (I2): 23.3% Outcome 10% weight loss Effect medication on achieving 10% weight loss; odds ratio(OR) [95% CI]: See eFigure 3B, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT Pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): OR=2.41; (95% CI=[2.08, 2.78]) favouring orlistat Heterogeneity (I2): 26.2% Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): OR=4.11; (95% CI=[2.80, 6.05]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion Heterogeneity (I2): 64.1% Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): OR=4.36; (95% CI=[3.61, 5.26]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 0% Outcome weight loss in Kg Effect medication on weight loss (in Kg); mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 3C, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT Pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-2.63; (95% CI=[-2.94, -2.32]) favouring orlistat Heterogeneity (I2): 26.3% Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-4.95; (95% CI=[-5.54, -4.36]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion Heterogeneity (I2): 0% Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-5.24; (95% CI=[-5.60, -4.87]) favouring liraglutide Heterogeneity (I2): 82.8%

|

Facultative: The authors conclude that among overweight or obese adults, orlistat, Naltrexon-bupropion, and liraglutide, compared with placebo, were each associated with achieving at least 5% weight loss at 52 weeks. Liraglutide was associated with the highest odds of achieving at least 5%weight loss

|

|

Khera, 2018 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to February 2017

Study design: RCT parallel group design (all included RCTs)

Setting and Country: See table eTable 1; Khera (2018) for country of the individual RCTs

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported for the individual studies |

Inclusion criteria SR: Treatment period >1 year; comparison with placebo; obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI ≥27 kg/m2) adults ( ≥18 years)

28 included studies

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See table eTable 1; Khera (2018) for baseline characteristics of the individual RCTs

|

Describe intervention - Orlistat (120 mg 3 times daily) - naltrexon-bupropion (32 mg/ 360mg twice daily) - Liraglutide (3 mg subcutaneous injection daily)

|

Describe control - Placebo |

End-point of follow-up -52 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) See table eTable 1; Khera (2018) for number of participants with complete outcome data in the intervention and control group.

|

Outcome fasting blood glucose Effect medication on blood glucose; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 1, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

Pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-5.71; (95% CI=[-7.84, -3.59]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 93.1%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-1.74; (95% CI=[-2.71, -0.77]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-15.78; (95% CI=[-28.06, -3.50]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 97.2%

Outcome hemaglobin A1c Effect medication on hemaglobin A1C; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 2, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

Pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-0.35; (95% CI=[-0.48, -0.22]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 59.5%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-0.50; (95% CI=[-0.78, -0.22]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-0.50; (95% CI=[-0.91, -0.09]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 98.0%

Outcome LDL Effect medication on LDL; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 3, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-9,21; (95% CI=[-12.02, -6.40]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 78.8%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-1.72; (95% CI=[-4.24, 0.80]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion

Heterogeneity (I2): 62.2%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-2.35; (95% CI=[-3.74, -0.97]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome HDL Effect medication on HDL; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 4, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-1.10; (95% CI=[-1.73, -0.46]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 66.4%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=2.72; (95% CI=[0.08, 5.37]) favouring placebo

Heterogeneity (I2): 96.1%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=0.88; (95% CI=[0.44, 1.33]) favouring placebo

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome systolic blood pressure Effect medication on systolic blood pressure; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 5, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-1.59; (95% CI=[-2.33, -0.86]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 26.6%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=0.42; (95% CI=[-1.27, 2.10]).

Heterogeneity (I2): 84.5%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-2.69; (95% CI=[-3.46, -1.91]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome diastolic blood pressure Effect medication on diastolic blood pressure; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 6, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-1.35; (95% CI=[-1.93, -0.77]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 31.7%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=0.04; (95% CI=[-0.89, 0.96])

Heterogeneity (I2): 72.1%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-0.73; (95% CI=[-1.28, -0.19]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome waist circumference Effect medication on waist circumference; mean difference [95% CI]: See eFigure 7, Khera (2016) for the outcome for each individual RCT

pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-2.28; (95% CI=[-2.89, -1.68]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 42.9%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-3.44; (95% CI=[-4.47, -2.41]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion

Heterogeneity (I2): 58.9%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-4.11; (95% CI=[-4.78, -3.45]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 41.5% |

Facultative: The authors conclude that orlistat, naltrexon-bupropion, and liraglutide, compared with placebo, appear to have minimal to modest effects on cardiometabolic risk profile of obese and overweight adults even after a year of drug therapy. |

|

Singh, 2020 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to September 2019

Study design: A-D double blind RCT

Study design: RCT parallel group design (all included RCTs)

Setting and Country: Not reported

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported for the individual studies |

Inclusion criteria SR: Phase 3 RCTs; placebo control group; duration ≥1 year. Comparison with placebo; obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI ≥27 kg/m2) adults ( ≥18 years)

31 included studies

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Partially reported for studies except orlistat. See Table 2; Singh (2020)

|

Describe intervention - Orlistat (120 mg 3 times daily) - naltrexon-bupropion (32 mg/ 360mg twice daily) - Liraglutide (3 mg subcutaneous injection daily)

|

Describe control - Placebo |

End-point of follow-up -52 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? See table Table 2; Singh (2020) for number of participants with complete outcome data except for orlistat.

|

Outcome weight loss in Kg Effect medication on weight loss (in Kg); mean difference [95% CI]: See Figure 1, 4 and 5; Singh (2020) for the outcome for each individual RCT

Pooled effect orlistat vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-3.066; (95% CI=[-3.763, -2.369]) favouring orlistat

Heterogeneity (I2): 80.56%

Pooled effect naltrexon-bupropion vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-4.386; (95% CI=[-5.053, -3.718]) favouring naltrexon-bupropion

Heterogeneity (I2): 50.11%

Pooled effect liraglutide vs placebo (random effects model): MD=-5.246; (95% CI=[-6,172, -4.321]) favouring liraglutide

Heterogeneity (I2): 65.8%

|

The authors conclude that among overweight or obese adults, orlistat, naltrexon-bupropion, and liraglutide, compared with placebo, were each associated with achieving a significant reduction of body weight

|

|

Zhong, 2022 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to September 2019

A: Friedrichsen, 2021 B: Rubino, 2021 C: Wadden, 2021 D: Wilding, 2021

Study design: RCT parallel group design (all included RCTs)

Setting and Country: Outpatient clinics in multiple countries

Study design: A-D double blind RCT

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Not reported for the individual studies |

Inclusion criteria SR: (1) enrolled participants were adults (≥18 years old) with a body-mass index of 27 kg/m2 or higher and without diabetes; (2) comparison of once-weekly semaglutide and placebo; (3) study design limited to RCTs; (4) outcomes of interest included data that were directly related to body weight change; (5) treatment duration lasted at least 20 weeks

Important patient characteristics at baseline: See supplementary table 1 (Zhong, 2022)

|

Describe intervention A-D: Once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg

|

Describe control A-D: Once-weekly Placebo

|

End-point of follow-up A: 20 weeks C-D: 68 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? Not reported for the individual studies

|

Outcome

Weight loss change (%) MD= -12.57% (95% CI -14.80 to -10.35) facvuring semaglutide

Weight loss change (kg) MD=-11.90 (95%CI -13.24 to-10.56) favouring semaglutide

Physical functioning score MD=1.75, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.58 favouring semaglutide

Physical component score MD=1.24, 95% CI 0.27–2.22 favouring semaglutide

Mental component score MD=2.90, 95% CI 1.54–4.26 favouring semaglutide

Glucose MD=–7.40 mg/dL, 95% CI –8.40 to –6.41 favouring semaglutide

Hb1Ac (%) MD=–0.25%, 95% CI –0.31 to –0.19 favouring semaglutide.

Total cholesterol Md=5.93% (95% CI 4.34 to 7.51) favouring semaglutide

LDL-cholesterol MD=6.55% (95% CI 4.19 to 8.92) favouring semaglutide

Triglycerides MD=18.34%, 95% CI –23.23 to –13.45) favouring semaglutide

Systolic bp MD=–4.62 mm Hg (95% CI –5.57 to –3.66) facouring semaglutide

Diastolic bp –1.82 mm Hg (95% CI –2.94 to –0.70) favouring semaglutide

Waist circumference (cm) MD=–9.34 cm (95% CI –10.00 to –8.68) favouring semaglutide |

The authors conclude that meta-analysis showed beneficial treatment effects of once-weekly ubcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg for adults with overweight or obesity on a comprehensive array of body weight-related efficacy endpoints |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy – otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question: What is the effect of pharmaceutical treatment combined with behavioural or lifestyle intervention compared to placebo in treating overweight and comorbidities or obesity in adults?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control © 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Chao, 2019 |

Type of study: Parallel group Randomized control trial

Setting and country: Single center, USA

Funding and conflicts of interest: Commercial, study is funded by Novo Nordisk and authors are on the advisory board of Novo Nordisk or receive grant money from Novo Nordisk |

Inclusion criteria: Aage 21-70 years; body mass index (BMI) of 30-55 kg/m2; and prior lifetime weight-loss effort with diet and exercise

Exclusion criteria: types 1 or 2 diabetes; personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2; bariatric surgery; renal, hepatic or recent cardiovascular disease (CVD); medications that substantially affect body weight; current major depression, suicidal ideation or history of suicide attempts; pregnancy/ lactation; or weight loss ≥4.5 kg in the past 3 months

N total at baseline: Liraglutide-ITD: n=50 Multicomponent: n=50 ITD-placebo: n=50

Important prognostic factors2:

age ± SD: 47.6 ± 11.8

Sex (%) 119 (79.3%)

BMI ± SD 38.4 ± 4.9

Weight, kg ± SD 108.4 ± 17.5

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Describe intervention:

All participants had 21 sessions of IBT, delivered by a physician, nurse practitioner or registered dietitian.Participants who weighed <113.6 kg were prescribed a diet of 1200- 1499 kcal/day (while those ≥113.6 kg received 1500-1800 kcal/day). Engage in low-to-moderate intensity physical activity 5 days per week, gradually building to ≥225 minutes/week. Intervention group also received 3.0mg/day liraglutide

|

Describe control:

IBT program without liraglutide

|

Length of follow-up: 52 weeks

Loss-to-follow-up; n (%): No loss to follow-up mentioned

Incomplete outcome data: No incomplete data

|

Outcome measures and effect size at 52 weeks:

I= IBT-alone L= IBT-Liraglutide M=Multicomponent

HRQoL IBT-alone (week 52) Mean ± SE; ; (P-value compared to IBT-Alone)

Physical component summary ± SD I: +4.4 ± 1.0 L: +2.1 ± 1.0; (P=0.11) M: +3.4 ± 1.0; (P=0.48)

Mental component summary ± SD I: +0.8 ± 1.3 L: +4.5 ± 1.3; (P=0.048) M: +6.4 ± 1.3; (P=0.003)

Physical functioning ± SD I: 79.9 ± 17.8 L: +10.3 ± 2.9; (P=0.60) M : +7.9 ± 3.0; (P=0.95)

Role physical ± SD I: +5.8 ± 4.7 L: +6.8 ± 4.6; (P=0.88) M: +16.0 ± 4.7; (P=0.12)

Bodily pain ± SD I: +11.1 ± 2.9 L: −1.2 ± 2.9; (P=0.003) M:+4.0 ± 2.9; (P=0.09)

General health ± SD I: +5.4 ± 2.2 L: +10.1 ± 2.2; (P=0.13) M: +8.8 ± 2.2; (P=0.28)

Vitality ± SD I: +14.2 ± 2.9 L: +11.0 ± 2.8; (P=0.43) M: +15.6 ± 2.8; (P=0.71)

Social functioning ± SD I: +5.2 ± 3.5 L: +6.8 ± 3.4; (P=0.75) M: +17.4 ± 3.4; P=0.01)

Role emotional ± SD I: −0.9 ± 4.9 L: +9.3 ± 4.9; (P=0.14) M: +16.2 ± 4.9; (P=0.01)

Mental health ± SD I:+0.9 ± 2.6 L: +9.6 ± 2.6; (P=0.02) M: +8.0 ± 2.6; (P=0.05)

Weight-related QoL (week 52): Mean ± SE; (P-value compared to IBT-Alone)

Total score ± SD I: +12.3 ± 2.1 L: +15.8 ± 2.1; (P=0.24) M: +19.4 ± 2.1; (P=0.02)

Physical function ± SD I:+14.4 ± 2.5 L: +17.4 ± 2.5; (P=0.40) M: +18.6 ± 2.5; (P=0.24)