Dosering van CRRT

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de optimale toegediende dosering van continue nierfunctievervangen therapie bij kritisch zieke patiënten met acute nierinsufficiëntie op de intensive care?

Aanbeveling

Kies bij continue nierfunctievervangende therapie bij kritisch zieke patiënten met AKI op de intensive care voor een voorgeschreven dosis (effluent volume) van 20-25 ml/kg/u, waarbij rekening gehouden moet worden met downtime.

Geef bij voorkeur intermitterende hemodialyse bij een refractaire, potentieel levensbedreigende hyperkaliëmie en/of bij intoxicaties.

Overweeg een hoge dosis continue nierfunctievervangende therapie (>35 ml/kg/u) in specifieke omstandigheden, zoals een refractaire, potentieel levensbedreigende hyperkaliëmie of bij bepaalde intoxicaties.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Er is literatuuronderzoek verricht naar de effecten van een hoge dosering van continue nierfunctie vervangende therapie (continuous renal replacement therapy, CRRT) (>35 ml/kg/u) versus een standaarddosering van CRRT (<35mL/kg/u) bij kritisch zieke patiënten op de intensive care (IC). Er is één systematische review geïncludeerd die de vergelijking tussen een hoge en standaarddosering van CRRT heeft onderzocht.

Op basis van de cruciale uitkomstmaten mortaliteit en herstel van nierfunctie komt er geen duidelijke voorkeur voor hoge of standaard dosis van CRRT naar voren bij kritisch zieke patiënten op de IC. Mortaliteit werd gerapporteerd op dag 30 en na meer dan 30 dagen post-randomisatie. Voor mortaliteit op dag 30 was de bewijskracht zeer laag en kon er geen conclusie worden getrokken op basis van de literatuur. Voor mortaliteit na meer dan 30 dagen post-randomisatie werd geen verschil gevonden (redelijke bewijskracht). Ook lijkt de dosering van CRRT niet tot nauwelijks effect te hebben op herstel van nierfunctie: bij een hoge dosis van CRRT leek er geen klinisch relevant verschil te zijn in het aantal patiënten dat vrij is van nierfunctie vervangende therapie na het stoppen met CRRT, zowel op dag 30 (lage bewijskracht) als op dag 90 (redelijke bewijskracht). Voor direct na het stoppen met CRRT is de bewijskracht zeer laag en kan geen conclusie worden getrokken op basis van de literatuur. De overall bewijskracht voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten is zeer laag. De cruciale uitkomstmaten kunnen daarom geen richting geven aan de besluitvorming.

De belangrijke uitkomstmaat complicaties (hypofosfatemie, hypokaliëmie en arrhythmie) toont aan dat er waarschijnlijk geen verschil is tussen een hoge of standaarddosering van CRRT (redelijke bewijskracht). De bewijskracht voor het aantal patiënten met complicaties en het aantal bloedingen is zeer laag. Er lijkt geen verschil te zijn tussen de twee groepen voor de duur van ziekenhuisopname en de duur van IC opname (lage bewijskracht). Er zijn geen studies gevonden die gekeken hebben naar het effect van een hoge dosering van CRRT op de duur van CRRT en op kwaliteit van leven.

In algemeenheid is op grond van de literatuuranalyse dus geen reden om te streven naar een hoge dosis CRRT (>35 ml/kg/u), daarbij vaststellend dat voor de cruciale uitkomst mortaliteit 30 dagen na behandeling een redelijke bewijskracht bestaat dat er waarschijnlijk geen verschil is met standaarddosis CRRT (<35 mL/kg/u). Dit komt overeen met eerder gevonden uitkomsten en vigerende richtlijnen (KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury, 2012). De standaarddosis in de studies was 20-25 mL/kg/u, wat overeenkomt met de Nederlandse praktijk.

De resultaten met betrekking tot de belangrijke eindpunten kwamen goed overeen met wat de klinische praktijk laat zien. In de praktijk wordt door sommigen gesuggereerd dat bij sepsis een hoog volume CRRT een betere cytokineklaring zou geven met positieve uitkomsten op overleving. In de onderzochte studies zijn patiënten met sepsis niet separaat geanalyseerd. De werkgroep kan evenwel, alhoewel deze vraag niet expliciet in de analyse meegenomen is, geen ondersteuning vinden voor de bijdrage van hoog volume CRRT op cytokineklaring en hieraan te linken reductie in mortaliteit. Park (2016) vergeleek 40 ml/kg/uur volume CVVHDF met hoog volume (80 ml/kg/u) CVVHDF op mortaliteit en cytokineklaring. Er bleek geen verschil in mortaliteit te zijn, ondanks dat bij de hoog volume groep de daling van de cytokines significant groter was. Hoewel het lage volume in dit onderzoek al hoger was dan de huidige standaarddosering, kan in ieder geval op grond van deze studie niet gesteld worden dat hogere volumes betere uitkomsten geven. In een kleine studie bij patiënten met brandwonden (Chung, 2017) vonden de auteurs weliswaar bij hoog volume (70 ml/kg/u) een belangrijke vermindering van vasopressorafhankelijkheid en een veel betere 14-dagen MODS-score, maar er was geen gunstig effect op mortaliteit en cytokineklaring. Het argument om bij septische patiënten hoog volume CRRT voor te schrijven, is derhalve niet te onderbouwen.

In de studies, waarin zowel de voorgeschreven als de toegediende dosis is gerapporteerd, was de toegediende dosis circa 80-85% van de voorgeschreven dosis. In enkele onderzoeken werd de down-time gecompenseerd door het ophogen van de dosering voor de resterende 24 uur.

Bij analyse van de studies viel op dat de methode voor het vaststellen van het lichaamsgewicht bij veel studies ontbrak. Dit heeft natuurlijk zijn weerslag op de werkelijk voorgeschreven behandeldosis op gewichtsbasis. Er is echter op dit moment geen evicence-based methode voor een eventuele aanpassing van de deliverd dose bij patienten met overgewicht. Daarom kunnen we hiervoor in deze richtlijn geen onderbouwd advies geven. Aangenomen wordt echter dat zowel onderschatting als overschatting even vaak voorkomen en dat correctie hiervoor niet noodzakelijk zou moeten zijn en feitelijk ook onmogelijk is.

De ATN-studie (2005) (geïncludeerd in Fayad, 2016) werd in de analyse meegenomen, ondanks het feit dat er zowel continue als intermitterende hemodialyse (drie en zes keer per week, respectievelijk standaard en hoge dosis) werd voorgeschreven. Deze verschillende technieken werden in ongeveer gelijke mate in de standaard en hoge dosis groep gevonden. De werkgroep acht derhalve het effect van puur de techniek niet klinisch relevant voor de vraagstelling.

Vanwege de vele en verschillende inclusiecriteria in de studies is besloten om dit als gegeven te erkennen en voor de vraagstelling laag of hoog volume als klinisch niet relevant te wegen. Correctie hiervoor is ook niet mogelijk. Opvallend is ook de grote heterogeniteit tussen de geïncludeerde onderzoeken ten aanzien van het type CRRT (CVVH, CVVHDF, SLED), het gebruik van pre- of post-dilutie en het type antistolling (heparine, LMWH, citraat). Daarnaast is slechts in één studie citraat als antistollingsmiddel gebruikt (zie Tabel 1 in ATN study, 2005), terwijl dit in de huidige praktijk overwegend gebruikt wordt. Alleen op het gebied van bloedingscomplicaties zou volgens de werkgroep gebruik van citraat de analyse kunnen beïnvloeden, maar gezien het feit dat het aantal gedocumenteerde bloedingscomplicaties laag was, wordt dit als niet verstorend beschouwd.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

De voorkeur van de patiënt of diens naasten voor een standaard of hoge dosis is niet onderzocht en is dus onbekend. Goede communicatie over de behandeldoelen, voor- en nadelen en risico’s van de CRRT-behandeling met de patiënt en/of diens naasten is belangrijk. Een hoge dosis van CRRT heeft waarschijnlijk geen voordelen. Tegelijkertijd heeft een hoge CRRT dosis wel potentiële nadelen, zoals metabole ontregeling, aanvoerproblemen van de centraal veneuze katheter en verhoogde klaring van wateroplosbare medicijnen, bijvoorbeeld antibiotica. Vanuit het perspectief van de patiënt en/of diens naasten is er dus mogelijk een voorkeur voor de standaarddosering (20-25 ml/kg/u). Belangrijk is wel dat de downtime zo kort mogelijk is en dat eventuele downtime gecompenseerd wordt, zodat de gemiddelde 24-uurs dosis uitkomt op minstens 20-25 ml/kg/u.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten voor de CRRT op de IC worden voor een groot deel bepaald door gebruik van de disposables, waaronder de vloeistoffen voor CRRT. Het ligt voor de hand dat een hoge CRRT-dosis gepaard gaat met een hoger verbruik van vloeistoffen en dus hogere kosten. Klinische studies naar de kosten van verschillende CRRT doses ontbreken echter op dit moment. Desondanks is het kostenaspect een ondersteunend argument voor het niet verhogen van de CRRT dosis.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep heeft geen onderbouwing kunnen vinden voor de meerwaarde van hoog-volume CRRT op de IC. Dat houdt onder andere in dat op IC-afdelingen waar reeds CRRT geïmplementeerd is, dit onverminderd en onveranderd kan worden gecontinueerd. Op het gebied van implementatie zal er dus niets veranderen. Een hoge CRRT dosis zou als gevolg hebben dat er een hoger verbruik is van de vloeistoffen en dat de vloeistofzakken vaker gewisseld moeten. Voor de zorgverleners betekent een hoog of zeer hoog volume CRRT een toename in werkbelasting en zelfs fysieke belasting.

De werkgroep is van mening dat er speciale indicaties bestaan voor het tijdelijk toepassen van een hoge dosis CRRT. Te denken valt bijvoorbeeld aan een ernstige refractaire hyperkaliëmie. Bij een ernstige hyperkaliëmie is intermitterende hemodialyse echter veel effectiever dan CRRT in het omlaag brengen van de plasma kaliumspiegel en hemodialyse is hierbij dan ook de eerste keuze. Een andere mogelijke indicatie voor een hoge CRRT dosis (>35 ml/kg/u) is het beter klaren van bepaalde toxische geneesmiddelen. Voorwaarde hiervoor is dat het bewuste farmacon een lage eiwitbinding heeft bij toxische doseringen (< 80%), niet te groot is, een klein verdelingsvolume heeft van < 1 l/kg en vooral voornamelijk renaal geklaard wordt (Hoff, 2020). Voorbeelden hiervan zijn lithium, ethyleenglycol of metformine. De klaring van deze middelen is echter veel hoger met hemodialyse dan met CRRT. Bij een ernstige intoxicatie met deze middelen is hemodialyse dan ook de eerste keuze. Indien er een dusdanige verdeling van het farmacon in het lichaam bestaat dat eenmalige hemodialyse gevolgd wordt door een rebound, kan hoog volume continue behandeling in aansluiting op de hemodialyse van extra waarde zijn. Bedenk in het licht van geneesmiddelen klaring, en dat geldt zeker ook voor antibiotica, dat de klaring qua techniek bepaald wordt door het oppervlak van de kunstniermembraan, de poriegrootte, het volume van het effluent en of er middels convectie, diffusie of een combinatie van beide geklaard wordt. IHD is het meest effectief in klaring. Ten aanzien van de verwijdering van vocht per 24 uur zijn CVVH, CVVHD en CVVHDF gelijkwaardig. Het totale volume vocht dat per 24 uur verwijderd kan worden is bij de contnue technieken doorgaans hoger dan tijdens een 3 tot 4 uur durende hemodialyse.

Tenslotte, en dat blijkt uit alle exclusiecriteria van de studiepopulaties die beschreven zijn, gelden de resultaten niet voor patiënten met een pre-existent reeds voortgeschreden chronisch nierfalen (doorgaans een creatinine >180 µmol/l). In hoeverre zij zich anders gedragen is echter nog niet onderzocht. Bij patiënten met chronisch nierfalen die reeds met peritoneale dialyse (PD) worden behandeld kan overwogen worden de PD op de IC te continueren als de expertise en/of ondersteuning door dialyse verpleegkundigen beschikbaar is. Onvoldoende klaring of onvoldoende verwijdering van vocht kan reden zijn om (tijdelijk) over te gaan op CRRT. Bij patiënten met chronisch nierfalen die met hemodialyse worden behandeld kan de hemodialyse vaak worden voortgezet waarbij het mogelijk moet zijn om de frequentie en duur van de hemodialyse aan te passen aan de metabole behoefte en de noodzaak tot ultrafiltratie van vocht. Bij hemodynamisch instabiele patienten zal vaak tijdelijk worden overgegaan op CRRT.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Er komt uit de analyse van de literatuur niet naar voren dat hoog volume CRRT (>35 ml/kg/uur) de voorkeur verdient boven een standaardvolume (20-25 ml/kg/u). Dit geldt vooral voor de belangrijkste uitkomstparameters mortaliteit en herstel van nierfunctie. De meta-analyse laat, met redelijke bewijskracht, zien dat er geen verschil is tussen standaard en hoog volume CRRT in de mortaliteit >30 dagen na randomisatie.

De werkgroep is van mening dat er speciale indicaties bestaan voor het toepassen van een hoge dosis CRRT, zoals een refractaire, potentieel levensbedreigende, hyperkaliëmie of in het geval van bepaalde intoxicaties. Bij een refractaire, potentieel levensbedreigende, hyperkaliëmie en bij intoxicaties met bijvoorbeeld lithium, ethyleenglycol en metformine is intermitterende hemodialyse echter de nierfunctievervangende behandeling van eerste keuze, omdat de correctie van de hyperkaliëmie en de daling van de toxische plasmaspiegels sneller is. In afwachting van starten met hemodialyse kan in dergelijke omstandigheden overwogen worden om te starten met CRRT met de maximaal haalbare dosis.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De dosis van continue nierfunctievervangende therapie (CRRT) wordt uitgedrukt in ml per kg lichaamsgewicht per uur (ml/kg/u). In de NVIC-richtlijn uit 2012 is het advies voor continue veno-veneuze hemofiltratie (CVVH), continue veno-veneuze hemodialyse (CVVHD) en continue veno-veneuze hemodiafiltratie (CVVHDF) een voorgeschreven dosis van 25 ml/kg/uur en wordt een hogere dosis dan 30-35 ml/uur/kg niet zinvol geacht. Met moderne apparatuur is het eenvoudig om een hogere dosis aan te bieden, maar het is de vraag of dit leidt tot betere uitkomsten. Een hogere dosis gaat weliswaar gepaard met een betere klaring van wateroplosbare uremische toxines, maar heeft ook potentiële nadelen zoals een grotere klaring van dialyseerbare medicatie en nutriënten zoals aminozuren. In deze module wordt nagegaan of het advies uit 2012 voor de CVVH(DF) dosis aangepast dient te worden.

Conclusies

Mortality (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a high prescribed dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy on 30-day mortality when compared with a standard prescribed dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

A high prescribed dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy likely results in little to no difference in mortality after 30 days post-randomisation when compared with a standard prescribed dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

Recovery of renal function (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a high prescribed dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy on recovery of renal function after discontinuing continuous renal replacement therapy when compared with a standard prescribed dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

|

Low GRADE |

A high dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy may result in little to no difference in the number of patients free of renal replacement therapy after discontinuing continuous renal replacement therapy at day 30 when compared with a standard dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

A high dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy likely results in little to no difference in the number of patients free of renal replacement therapy after discontinuing continuous renal replacement therapy at day 90 when compared with a standard dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

Duration of RRT and quality of life (important)

|

No GRADE |

No evidence was found regarding the effect of a high dose of renal replacement therapy on the duration of RRT and on quality of life when compared with a standard dose of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving RRT. |

Length of hospital and ICU stay (important)

|

Low GRADE |

A high dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy may result in little to no difference in length of hospital and ICU stay when compared with a standard dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

Complications (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a high prescribed dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy on the number of patients experiencing adverse events and the number of bleeding events when compared with a standard prescribed dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

A high dose (>35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy likely results in little to no difference in hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia and arrhythmia when compared with a standard dose (<35 mL/kg/h) of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients receiving CRRT.

Source: Fayad, 2016 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Fayad (2016) conducted a systematic review of RCTs and meta-analysis to assess the effects of different intensities of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) on mortality and recovery of renal function in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury (AKI). The Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialized Register was searched up to the 9th of February 2016. Studies in the Specialized Register were identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE. Additionally, LILACS and reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines were searched. Lastly, letters were written to researchers/authors involved in previously published relevant studies to obtain information about unpublished or incomplete studies. Studies were included in the review if they included patients that were admitted to the ICU with AKI and receiving CRRT, regardless of gender or age. Intensive versus less intensive CRRT was compared, defined as a prescribed dose of >35 mL/kg/h and <35 mL/kg/h, respectively. All CRRT modalities were included, being CVVH, CVVHD and CVVHDF. Included outcome measures were mortality, recovery of renal function, length of stay, metabolic control, and adverse events. A total of six studies enrolling 3185 patients were included in this systematic review. For the current analysis, only five out of six studies were included, as one study (Saudan, 2006) included a different RRT modality in the intervention group (CVVHDF) than in the control group (CVVH). One study (Ronco, 2000) included three different CRRT intensities (standard, intermediate and high). For this analysis, the intermediate and high intensity group were combined into one high intensity arm. Another study (Bouman, 2002) also included three groups: an early plus high volume hemofiltration group (prescribed dose >72 L/d and delivered dose 48.2 mL/kg/h), an early plus low-volume hemofiltration group, and a late plus low-volume hemofiltration group. The latter two groups received the same CRRT dose (24 to 36 L/d and delivered dose 19 to 20 mL/kg/h) but differed in timing of CRRT initiation. These two groups were combined into one low-volume hemofiltration arm. Overall, the prescribed dose of CRRT in the less intensive treatment ranged between 20 and 25 mL/kg/h, versus 35 to 48 mL/kg/h in the intensive treatment arm. Study characteristics and inclusion criteria of the included studies are described in Table 1. More elaborate study details can be found in the evidence table. The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials was used to assess the risk of bias in the included RCTs. Studies were either assessed as low or unclear risk of bias. Only the performance of blinding of participants and personnel was unclear in all included studies, and two studies (Ronco, 2000; Bouman, 2002) had an unclear risk of other bias. Other domains were assessed as low risk of bias.

Table 1. Study characteristics and inclusion criteria for each of the included studies in Fayad (2016).

|

Study |

Inclusion criteria |

Intervention (n) |

Control (n) |

Modality |

Hemofilter |

Replace-ment fluid |

Anticoagu-lation |

|

ATN study, 2005 |

Critically ill patients aged >18 years with AKI due to ATN who require RRT defined as |

Intensive management strategy (n=563) - If hemodynamically stable: IHD 6 times/week (target delivered Kt/V ˜ 1.2 to 1.4/treatment) - If hemodynamically unstable: CVVHDF at 35 mL/kg/h; or SLED, 6 times/week (target delivered Kt/V ˜ 1.2 to 1.4/treatment) |

Conventional management strategy (n=561) - If hemodynamically stable: IHD 3 times/week (target delivered Kt/V ˜ 1.2 to 1.4/treatment) - If hemodynamically unstable: CVVHDF at 20 mL/kg/h; or SLED, 3 times/week (target delivered Kt/V ˜ 1.2 to 1.4/treatment) |

IHD, CVVHDF, SLED |

cellulose triacetate or synthetic membranes |

predilution mode |

heparin, citrate, other |

|

Bouman, 2002 |

Patients with circulatory and respiratory insufficiency and early AKI who need CRRT; CrCl <20 mL/ min, and oliguria <180 mL/6 h despite fluid resuscitation; circulatory support and furosemide; early timing: <12 h inclusion; late timing: BUN >40 mmol/L or severe pulmonary oedema. |

Early + high volume hemofiltration group (n=35) Treatment started within 12 h after time of inclusion, and the ultrafiltration flow rate was high (prescribed dose >72 L/d and delivered dose 48.2 mL/kg/h) |

- Early + low-volume hemofiltration group (n=35): treatment started within 12 h after time of inclusion, and the ultrafiltration flow rate was low (prescribed dose 24 to 36 L/d and delivered dose 19 to 20 mL/kg/h) - Late + low-volume hemofiltration group (n=36): treatment started when the patient fulfilled the conventional criteria for RRT: urea level 40 mmol/L, potassium 6.5 mmol/L or severe pulmonary oedema, and the ultrafiltration flow rate was low (24 to 36 L/d and delivered dose 19 to 20 mL/kg/h)

|

CVVH |

cellulose triacetate hollow-fibre |

postdilution mode with bicarbonate solution |

heparin or nadroparin |

|

RENAL study, 2006 |

Critically ill AKI patients who need CRRT; oliguria (urine output < 100 mL in 6 h period) unresponsive to fluid resuscitation measures; potassium >6.5 mmol; severe acidemia pH <7.2/L; urea nitrogen level >70 mg/dL or 25 mmol/L; SCr >3.4 mg/dL or 300 µmol/L; pulmonary oedema |

Higher intensity CRRT (n=722): prescribed dose: 40 mL/kg/h of effluent dose (delivered dose 33.4 ± 12.8 mL/kg/h) |

Lower intensity CRRT (N=743): prescribed dose: 25 mL/kg/h of effluent dose (delivered dose 22 ± 17.8 mL/kg/h) |

CVVHDF |

polyacrylonitrile hollow-fibre |

post-dilution mode with bicarbonate solution |

N.R. |

|

Ronco, 2000 |

Critically ill AKI patients who need CRRT; admission to ICU |

Group 1 (n=139): Higher intensity CRRT: prescribed dose: 35 mL/kg/h (delivered dose 33.5 mL/kg/h) Group 2 (n=140): Higher intensity CRRT: prescribed dose: 45 mL/kg/h (delivered dose 42.5 mL/kg/h) |

Lower intensity CRRT (n=146): prescribed dose: 20 mL/kg/h (delivered dose 19 mL/kg/h) |

CVVH |

polysulfone hollow-fibre |

post-dilution mode with lactate solution |

systemic heparin |

|

Tolwani, 2008 |

Critically ill patients with AKI who need CRRT; AKI was mostly medical-volume overload despite diuretics; oliguria (urine output <200 mL/12 h) despite fluid resuscitation and diuretics; anuria (urine output <50 mL/12 h); azotemia (BUN >80 mg/dL); hyperkalemia (K >6.5 mmol/L); SCr increase >2.5 mg/dL from normal values or a sustained rise in SCr >1 mg/dL over baseline |

Higher intensity CRRT (n=100): prescribed dose: 35 mL/kg/h |

Lower intensity CRRT (n=100): prescribed dose: 25 mL/kg/h |

CVVHDF |

polyacrylonitrile hollow-fibre |

predilution mode |

heparin or no anticoagulation |

The study of Saudan (2006) is not shown in the table and is not considered in this analysis.

Abbreviations: CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; NR, not reported; sCr, serum creatinine.

Results

Mortality

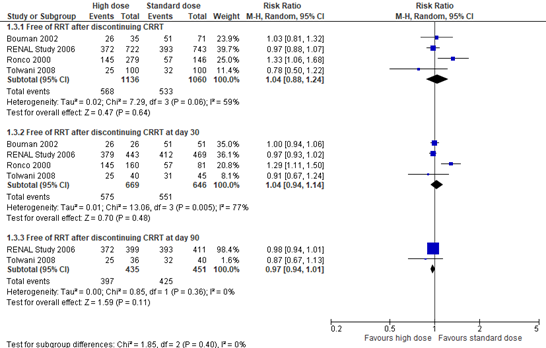

Four studies in Fayad (2016) reported mortality at day 30 and mortality after 30 days post-randomization. A total of 467 out of 1136 patients had died at day 30 in the high dose group, versus 438 out of 1060 patients in the standard dose group. The pooled risk ratio (RR) was 0.93 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.16, Figure 1), in favor of high dose of CRRT. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

A total of 628 out of 1253 patients died after 30 days post-randomization in the high dose group, versus 653 out of 1300 patients in the standard dose group. The pooled RR was 0.99 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.07, Figure 1), in favor of high dose of CRRT. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 1: 30-day mortality and mortality after 30 days post-randomisation; high versus standard dose of CRRT

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Recovery of renal function

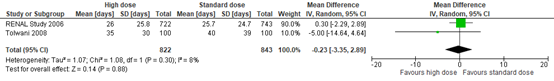

Four studies in Fayad (2016) reported the number of patients free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at different time points. A total of 568 out of 1136 patients were free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT in the high dose group, versus 533 out of 1060 patients in the standard dose group. The pooled RR was 1.04 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.24), in favor of standard dose of CRRT. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

A total of 575 out of 669 patients were free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at day 30 in the high dose group, versus 551 out of 646 patients in the standard dose group. The pooled RR was 1.04 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.14), in favor of standard dose of CRRT. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

A total of 397 out of 435 patients were free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at day 90 in the high dose group, versus 425 out of 451 patients in the standard dose group. The pooled RR was 0.97 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.01), in favor of high dose of CRRT. This difference was not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 2: Number of patients free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT; high versus standard dose of CRRT

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Duration of RRT

Fayad (2016) did not report the duration of RRT.

Length of hospital stay

Two studies in Fayad (2016) reported the length of hospital stay in days. Results are reported in Figure 3. The mean difference (MD) was -0.23 days (95% CI -3.35 to 2.89) in favor of intensive RRT. This difference was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 3: Mean length of hospital stay in days; high versus standard dose of CRRT

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

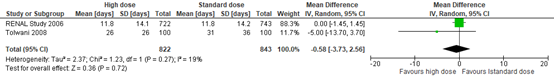

Length of ICU stay

Two studies in Fayad (2016) reported the length of hospital stay in days. Results are reported in Figure 4. The mean difference (MD) was -0.58 days (95% CI -3.73 to 2.56) in favor of intensive RRT. This difference was not considered to be a clinically relevant difference.

Figure 4: Mean length of ICU stay in days; high versus standard dose of CRRT

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Quality of life

Fayad (2016) did not report quality of life.

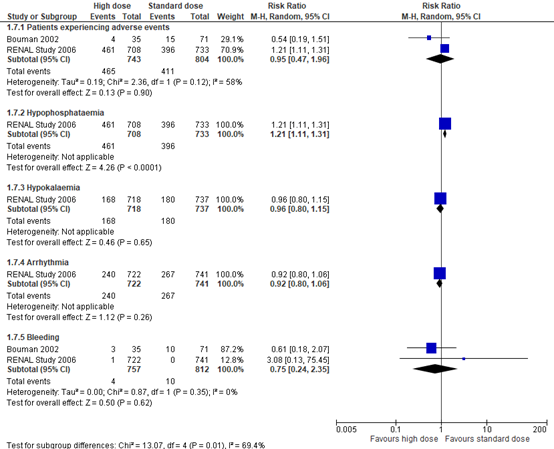

Complications

Two studies in Fayad (2016) reported the number of patients reporting adverse events and bleeding events. One of these studies (RENAL study, 2006) also reported on hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia and arrhythmia. The results are depicted in Figure 5. The pooled RR’s were 0.95 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.96) for the number of patients experiencing adverse events (in favor of high dose of CRRT), and 0.75 (95% CI 0.24 to 2.35) for bleeding events (in favor of high dose of CRRT).

The RENAL study (2006) (Fayad, 2016) reported a RR of 1.21 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.31) for hypophosphatemia (in favor of standard dose of CRRT), a RR of 0.96 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.15) for hypokalemia (in favor of high dose of CRRT), and a RR of 0.92 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.06) for arrhythmia (in favor of high dose of CRRT), and a RR of 0.75 (95% CI 0.24 to 2.35) for bleeding (Figure 5).

The pooled RR for bleeding was considered to be a clinically relevant difference in favor of high dose of CRRT, whereas the pooled RR’s for the number of patients experiencing adverse events, hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia and arrhythmia were not considered to be clinically relevant.

Figure 5: Adverse events; high versus standard dose of CRRT

Z: p-value of overall effect; df: degrees of freedom; I2: statistical heterogeneity; CI: confidence interval; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for all outcome measures was based on randomized trials and therefore started at high.

Mortality

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality at day 30’ was downgraded to very low, because of heterogeneity between studies in RRT modality, type of anticoagulation and the use of pre- and post-dilution (bias due to indirectness, -1); and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper boundary for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality after 30 days post-randomization’ was downgraded to moderate, because of heterogeneity between studies in RRT modality, type of anticoagulation and the use of pre- and post-dilution (bias due to indirectness, -1).

Recovery of renal function

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 'free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT' was downgraded to very low, because of heterogeneity between studies in RRT modality, type of anticoagulation and the use of pre- and post-dilution (bias due to indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 'free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at day 30' was downgraded to low because of heterogeneity between studies in RRT modality, type of anticoagulation and the use of pre- and post-dilution (bias due to indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 'free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at day 90' was downgraded to moderate because critically ill patients with AKI in CRRT have high short-term mortality risk and mortality is a competing end point for kidney recovery at day 90 (risk of bias, -1).

Duration of RRT

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘duration of RRT’ could not be established, as Fayad (2016) did not report duration of RRT.

Length of hospital stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 'length of hospital stay’ was downgraded to low because of the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Length of ICU stay

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure 'length of ICU stay' was downgraded to low because of the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Quality of life

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘quality of life’ could not be established, as Fayad (2016) did not report quality of life.

Complications

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘patients experiencing adverse events' was downgraded to very low because of heterogeneity between studies in RRT modality, type of anticoagulation and the use of pre- and post-dilution (bias due to indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypophosphatemia’ was downgraded to moderate because of the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypokalemia’ was downgraded to moderate because of the inclusion of the lower limit for clinical relevance in the confidence interval around the point estimate (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘arrhythmia’ was downgraded to moderate because of the inclusion of the lower limit for clinical relevance in the confidence interval around the point estimate (imprecision, -1).

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘bleeding events’ was downgraded to very low because of heterogeneity between studies in RRT modality, type of anticoagulation and the use of pre- and post-dilution (bias due to indirectness, -1), and the confidence interval around the point estimate crossing the lower and upper limit for clinical relevance (imprecision, -2).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What are the benefits and harms of a high dose versus a standard dose of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in critically ill adult patients with acute kidney injury (AKI)?

P: critically ill adult patients with AKI receiving CRRT

I: high dose of CRRT (>35 mL/kg/h)

C: standard dose of CRRT (<35 mL/kg/h)

O: mortality, recovery of renal function, length of hospital and ICU stay, duration of CRRT, quality of life, complications (due to CRRT in general and due to high dose of CRRT).

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered mortality and recovery of renal function as critical outcome measures for decision making and length of hospital and ICU stay, duration of CRRT, quality of life, and complications (due to CRRT in general and due to high dose of CRRT) as important outcome measures for decision making.

The working group did not define the outcome measures listed above a priori, but used the definitions used in the studies. A high dose of RRT was defined as a prescribed dose of >35 mL/kg/h, and a standard dose of RRT was defined as a prescribed dose of <35 mL/kg/h.

The ‘delivered dose’ is lower than the prescribed dose due to ‘downtime’ and because the diffusion across the semipermeable membrane decreases over time due to clotting and/or deposition of proteins in part of the fibers. The mode of CRRT (CVVH, CVVHD or CVVHDF), and the type of anticoagulation (heparin, LMWH or citrate) as well as the material of the dialyser may influence the delivered dose because of differences in the rate of coagulation, protein deposition in the fibers and differences in predilution. Because of the heterogeneity in all these factors (downtime, mode of CRRT, anticoagulation, material of the filter) and since not all studies reported the delivered dose, we used the prescribed dose in this analysis.

The working group defined 10% (RR <0.9 or >1.1) as a minimal clinically patient important difference for mortality and recovery of renal function, 2 days for duration of RRT and hospital length of stay, 1 day for ICU length of stay, a difference of 10% for quality of life-questionnaires (RR <0.9 or >1.1), and 25% (RR <0.8 or >1.25) for complications.

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until the 26th of July 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 282 unique hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- Systematic reviews and RCTs;

- Comparing a standard dose (<35 mL/kg/h) with a high dose of CRRT (>35 mL/kg/h) for critically ill patients receiving CRRT;

- Looking at mortality, recovery of renal function, length of hospital and/or ICU stay, duration of CRRT, quality of life and/or complications.

A total of 24 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 23 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study was included.

Results

One systematic review was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Chung KK, Coates EC, Smith DJ Jr, Karlnoski RA, Hickerson WL, Arnold-Ross AL, Mosier MJ, Halerz M, Sprague AM, Mullins RF, Caruso DM, Albrecht M, Arnoldo BD, Burris AM, Taylor SL, Wolf SE; Randomized controlled Evaluation of high-volume hemofiltration in adult burn patients with Septic shoCk and acUte kidnEy injury (RESCUE) Investigators. High-volume hemofiltration in adult burn patients with septic shock and acute kidney injury: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2017 Nov 25;21(1):289. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1878-8. PMID: 29178943; PMCID: PMC5702112.

- Fayad AI, Buamscha DG, Ciapponi A. Intensity of continuous renal replacement therapy for acute kidney injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 4;10(10):CD010613. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010613.pub2. PMID: 27699760; PMCID: PMC6457961.

- Hoff BM, Maker JH, Dager WE, Heintz BH. Antibiotic Dosing for Critically Ill Adult Patients Receiving Intermittent Hemodialysis, Prolonged Intermittent Renal Replacement Therapy, and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: An Update. Ann Pharmacother. 2020 Jan;54(1):43-55. doi: 10.1177/1060028019865873. Epub 2019 Jul 25. PMID: 31342772.

- Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179-84. doi: 10.1159/000339789. Epub 2012 Aug 7. PMID: 22890468.

- VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trial Network; Palevsky PM, Zhang JH, O'Connor TZ, Chertow GM, Crowley ST, Choudhury D, Finkel K, Kellum JA, Paganini E, Schein RM, Smith MW, Swanson KM, Thompson BT, Vijayan A, Watnick S, Star RA, Peduzzi P. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 3;359(1):7-20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802639. Epub 2008 May 20. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2009 Dec 10;361(24):2391. PMID: 18492867; PMCID: PMC2574780.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

|

Fayad, 2016

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to February 2016

A: ATN study, 2005 B: Bouman, 2002 C: RENAL study, 2006 D: Ronco, 2000 E: Saudan, 2006 F: Tolwani, 2008

Study design: RCT

Setting and Country: A: multicentre, USA B: two centres, The Netherlands C: multicentre, Australia and New Zealand D: two centres, Italy E: single centre, Switzerland F: single centre, USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest and funding reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR: Patients who received dialysis treatment before admission to ICU, patients admitted for drug overdose (doses exceeding therapeutic requirements), or with acute poisoning (all toxins).

Six studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Mean age in yrs (SD) A: B: C: D: I2: 63 (12) C: 61 (10) E: I: 65 (12) C: 62 (15) F: I: 56 (16)

Sex (M/F) A: B: C: I: 474/248 C: 472/271 D: I2: 80/60 C: 61/65 E: I: 65/37 C: 57/47 F: I: 59/41

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

Describe intervention:

A: n=563 Intensive management strategy

B: Group 1 (n=35): Early + high volume hemofiltration group: treatment started within 12 h after time of inclusion, and the ultrafiltration flow rate was high (prescribed dose > 72 L/d and delivered dose 48.2 mL/kg/h) dose 24 to 36 L/d and delivered dose 19 to 20 mL/kg/h) C: Higher intensity CRRT (n=722): prescribed dose: 40 mL/kg/h of effluent dose (delivered dose 33.4 ± 12.8 mL/kg/h) D: Group 1 (n=139): Higher intensity CRRT: prescribed dose: 35 mL/kg/h (delivered dose 33.5 mL/kg/h) Group 2 (n=140): Higher intensity CRRT: prescribed dose: 45 mL/kg/h (delivered dose 42.5 mL/kg/h) E: Higher intensity CRRT (n=102): CVVHDF, prescribed dose: 42 mL/kg/h F: Higher intensity CRRT (n=100): prescribed dose: 35 mL/kg/h

|

Describe control:

A: n=561

B: Late + low-volume hemofiltration group (n=36): treatment started when the patient fulfilled the conventional criteria for RRT: urea level 40 mmol/L, potassium 6.5 mmol/L or severe pulmonary oedema, and the ultrafiltration flow rate was low (24 to 36 L/d and delivered dose 19 to 20 mL/kg/h) C: Lower intensity CRRT (N=743): prescribed dose: 25 mL/kg/h of effluent dose (delivered dose 22 ± 17.8 mL/kg/h) D: Lower intensity CRRT (n=146): prescribed dose: 20 mL/kg/h (delivered dose 19 mL/kg/h) E: Lower intensity CRRT (n=104): CVVH, prescribed dose: 25 mL/kg/h F: Lower intensity CRRT (n=100): prescribed dose: 25 mL/kg/h

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 60 days B: 28 days C: 90 days D: 15 days E: 90 days F: 30 days

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: 99.55% of patientscomplete B: No incomplete data reported C: Complete follow-up data D: No loss to follow-up E: No dropouts or losses to follow up F: Percent followed: 100%

|

Mortality Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 0.88 (0.47, 1.64) C: 1/04 (0.92, 1.19) D: 0.72 (0.60, 0.88) E: 0.68 (0.52, 0,90) F: 1.09 (0.86, 1.39) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

Recovery of renal function The number of patients free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 1.03 (0.81, 1.32) C: 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) D: 1.33 (1.06, 1.68) E: 1.68 (1.15, 2.45) F: 0.78 (0.50, 1.22) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

The number of patients free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at day 30 Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) C: 0.97 (0.93, 1.02) D: 1.29 (1.11, 1.50) E: 1.02 (0.94, 1.11) F: 0.91 (0.67, 1.24) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

The number of patients free of RRT after discontinuing CRRT at day 90 Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: C: 0.98 (0.94, 1.01) E: 1.11 (0.87, 1.41) F: 0.87 (0.67, 1.13) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

Duration of hospital stay Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: C: 0.30 (-2.29, 2.89) F: -5.00 (-14.64, 4,64) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

Duration of ICU stay Effect measure: mean difference [95% CI]: C: 0.00 (-1.45, 1.45) F: -5.00 (-13.70, 3.70) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

Duration of RRT

Quality of life

Complications Patients experiencing adverse events Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 0.54 (0.19, 1.51) C: 1.21 (1.11, 1.31) E: 0.98 (0.06, 15.47) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

hypophosphatemia Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: C: 1.21 (1.11, 1.31)

Hypokalaemia Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: C: 0.96 (0.80, 1.15)

Arrhythmia Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: C: 0.92 (0.80, 1.06)

Bleeding Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: B: 0.61 (0.18, 2.07) C: 3.08 (0.13 (75.45) E: 0.98 (0.06, 15.47) Pooled effect (random effects model): see literature analysis.

|

Brief description of author’s conclusion With available data of included RCTs, more intensive CRRT (range between 35 to 48 mL/kg/h) demonstrated no beneficial effects on mortality or recovery of renal function, however there was an increased risk of hypophosphatemia compared to less intensive therapy (range between 20 to 25 mL/kg/h). The absence of high quality evidence of efficacy and the possibility of increased adverse events do not support the routine use of high intensity CRRT in this group of patients. However, in patients with post-surgical AKI, high intensity CRRT appears to reduce the risk of death.

|

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/not applicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Fayad, 2016 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

N.A. |

Yes |

Yes. If there was heterogeneity, sensitivity analyses were performed |

Yes |

Yes |

Table of excluded studies

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Xu Q, Jiang B, Li J, Lu W, Li J. Comparison of filter life span and solute removal during continuous renal replacement therapy: convection versus diffusion - A randomized controlled trial. Ther Apher Dial. 2022 Oct;26(5):1030-1039. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.13787. Epub 2022 Jan 12. PMID: 34967496. |

Study compares CVVH to CVVHDF. Doses between groups are the same (~35 ml/kg/h) – does not fit the PICO |

|

Vijayan A, Delos Santos RB, Li T, Goss CW, Palevsky PM. Effect of Frequent Dialysis on Renal Recovery: Results From the Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study. Kidney Int Rep. 2017 Dec 6;3(2):456-463. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.11.018. PMID: 29725650; PMCID: PMC5932307. |

Study compared intensive RRT (6 days per week) with less intensive RRT (3 days per week), no doses – does not fit the PICO

|

|

Junhai Z, Beibei C, Jing Y, Li L. Effect of High-Volume Hemofiltration in Critically Ill Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med Sci Monit. 2019 May 28;25:3964-3975. doi: 10.12659/MSM.916767. PMID: 31134957; PMCID: PMC6582686. |

Fits the PICO, but a more complete review (with more outcome measures) is available

|

|

Luo Y, Sun G, Zheng C, Wang M, Li J, Liu J, Chen Y, Zhang W, Li Y. Effect of high-volume hemofiltration on mortality in critically ill patients: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Sep;97(38):e12406. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012406. PMID: 30235713; PMCID: PMC6160258. |

Fits the PICO, but a more complete review (with more outcome measures) is available

|

|

Wang, Y., Jiang, W., Chen, C., Sheng, H., Mao, E., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Clinical efficacy of high-volume hemofiltration on severe acute pancreatitis combined with acute renal failure. |

No dose reported per group |

|

Mc Causland FR, Asafu-Adjei J, Betensky RA, Palevsky PM, Waikar SS. Comparison of Urine Output among Patients Treated with More Intensive Versus Less Intensive RRT: Results from the Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 Aug 8;11(8):1335-42. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10991015. Epub 2016 Jul 22. PMID: 27449661; PMCID: PMC4974887. |

No clear comparison between doses: study reports RRT for multiple times a week, plus the doses were merged/thrown together in one group. Does not fit the PICO.

|

|

Bellomo R, Lipcsey M, Calzavacca P, Haase M, Haase-Fielitz A, Licari E, Tee A, Cole L, Cass A, Finfer S, Gallagher M, Lee J, Lo S, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Myburgh J, Scheinkestel C; RENAL Study Investigators and ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Early acid-base and blood pressure effects of continuous renal replacement therapy intensity in patients with metabolic acidosis. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Mar;39(3):429-36. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2800-0. Epub 2013 Jan 11. PMID: 23306586. |

Wrong study design (nested cohort study) |

|

Combes A, Bréchot N, Amour J, Cozic N, Lebreton G, Guidon C, Zogheib E, Thiranos JC, Rigal JC, Bastien O, Benhaoua H, Abry B, Ouattara A, Trouillet JL, Mallet A, Chastre J, Leprince P, Luyt CE. Early High-Volume Hemofiltration versus Standard Care for Post-Cardiac Surgery Shock. The HEROICS Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Nov 15;192(10):1179-90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0516OC. PMID: 26167637. |

Wrong patient group (patients with severe shock requiring high-dose catecholamines 3–24 hours post–cardiac surgery) |

|

Zhang P, Yang Y, Lv R, Zhang Y, Xie W, Chen J. Effect of the intensity of continuous renal replacement therapy in patients with sepsis and acute kidney injury: a single-center randomized clinical trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012 Mar;27(3):967-73. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr486. Epub 2011 Sep 2. PMID: 21891773. |

Wrong definition of doses |

|

Li P, Qu LP, Qi D, Shen B, Wang YM, Xu JR, Jiang WH, Zhang H, Ding XQ, Teng J. High-dose versus low-dose haemofiltration for the treatment of critically ill patients with acute kidney injury: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017 Oct 22;7(10):e014171. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014171. PMID: 29061597; PMCID: PMC5665234. |

Study only reports Odds Ratio’s and no incidence rates |

|

Borthwick EM, Hill CJ, Rabindranath KS, Maxwell AP, McAuley DF, Blackwood B. High-volume haemofiltration for sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Jan 31;(1):CD008075. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008075.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 31;1:CD008075. PMID: 23440825. |

Old version - updated in 2017 |

|

Borthwick EM, Hill CJ, Rabindranath KS, Maxwell AP, McAuley DF, Blackwood B. High-volume haemofiltration for sepsis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 31;1(1):CD008075. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008075.pub3. PMID: 28141912; PMCID: PMC6464723. |

Only sepsis patients included, broader review preferred |

|

Clark E, Molnar AO, Joannes-Boyau O, Honoré PM, Sikora L, Bagshaw SM. High-volume hemofiltration for septic acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2014 Jan 8;18(1):R7. doi: 10.1186/cc13184. PMID: 24398168; PMCID: PMC4057068. |

Only sepsis patients included, broader review preferred |

|

Lehner GF, Wiedermann CJ, Joannidis M. High-volume hemofiltration in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014 May;80(5):595-609. Epub 2013 Nov 29. PMID: 24292260. |

Wrong definition of doses |

|

Liu C, Li M, Cao S, Wang J, Huang X, Zhong W. Effects of HV-CRRT on PCT, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10 in patients with pancreatitis complicated by acute renal failure. Exp Ther Med. 2017 Oct;14(4):3093-3097. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4843. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28912860; PMCID: PMC5585724. |

Wrong outcome measures |

|

Park JT, Lee H, Kee YK, Park S, Oh HJ, Han SH, Joo KW, Lim CS, Kim YS, Kang SW, Yoo TH, Kim DK; HICORES Investigators. High-Dose Versus Conventional-Dose Continuous Venovenous Hemodiafiltration and Patient and Kidney Survival and Cytokine Removal in Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016 Oct;68(4):599-608. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.02.049. Epub 2016 Apr 12. PMID: 27084247. |

Wrong definition of doses |

|

Chung KK, Coates EC, Smith DJ Jr, Karlnoski RA, Hickerson WL, Arnold-Ross AL, Mosier MJ, Halerz M, Sprague AM, Mullins RF, Caruso DM, Albrecht M, Arnoldo BD, Burris AM, Taylor SL, Wolf SE; Randomized controlled Evaluation of high-volume hemofiltration in adult burn patients with Septic shoCk and acUte kidnEy injury (RESCUE) Investigators. High-volume hemofiltration in adult burn patients with septic shock and acute kidney injury: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Crit Care. 2017 Nov 25;21(1):289. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1878-8. PMID: 29178943; PMCID: PMC5702112. |

Unclear inclusion criteria and difference interventions between groups

|

|

Joannes-Boyau O, Honoré PM, Perez P, Bagshaw SM, Grand H, Canivet JL, Dewitte A, Flamens C, Pujol W, Grandoulier AS, Fleureau C, Jacobs R, Broux C, Floch H, Branchard O, Franck S, Rozé H, Collin V, Boer W, Calderon J, Gauche B, Spapen HD, Janvier G, Ouattara A. High-volume versus standard-volume haemofiltration for septic shock patients with acute kidney injury (IVOIRE study): a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Sep;39(9):1535-46. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2967-z. Epub 2013 Jun 6. PMID: 23740278. |

Wrong definition of doses |

|

O'Brien Z, Cass A, Cole L, Finfer S, Gallagher M, McArthur C, McGuiness S, Myburgh J, Bellomo R, Mårtensson J; RENAL Study Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Clinical Trials Group. Higher versus Lower Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy Intensity in Critically ill Patients with Liver Dysfunction. Blood Purif. 2018;45(1-3):36-43. doi: 10.1159/000480224. Epub 2017 Nov 22. PMID: 29161684. |

Wrong study design (Post-hoc analysis) |

|

Yin F, Zhang F, Liu S, Ning B. The therapeutic effect of high-volume hemofiltration on sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020 Apr;8(7):488. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.48. PMID: 32395532; PMCID: PMC7210131. |

Only sepsis patients included, broader review preferred |

|

Quenot JP, Binquet C, Vinsonneau C, Barbar SD, Vinault S, Deckert V, Lemaire S, Hassain AA, Bruyère R, Souweine B, Lagrost L, Adrie C. Very high volume hemofiltration with the Cascade system in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 2015 Dec;41(12):2111-20. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4056-y. Epub 2015 Oct 2. PMID: 26431720. |

Wrong comparison (usual care is not good explained and the technique used for the cascade group is not common) |

|

Mathew A, McLeggon JA, Mehta N, Leung S, Barta V, McGinn T, Nesrallah G. Mortality and Hospitalizations in Intensive Dialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018 Jan 10;5:2054358117749531. doi: 10.1177/2054358117749531. PMID: 29348924; PMCID: PMC5768251. |

Wrong comparison |

|

Wang Y, Gallagher M, Li Q, Lo S, Cass A, Finfer S, Myburgh J, Bouman C, Faulhaber-Walter R, Kellum JA, Palevsky PM, Ronco C, Saudan P, Tolwani A, Bellomo R. Renal replacement therapy intensity for acute kidney injury and recovery to dialysis independence: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018 Jun 1;33(6):1017-1024. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfx308. PMID: 29186517. |

Fits the PICO, but but a more complete review (with more outcome measures) is available |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 18-06-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 18-06-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-07-2027

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten. (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS) en/of andere bron.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2022 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor kritisch zieke patiënten die in aanmerking komen voor continue nierfunctievervangende therapie op de intensive care.

Werkgroep

drs. M. (Meint) Volbeda, internist-intensivist, UMCG Groningen, NVIC (voorzitter)

drs. P.M. (Pauline) Klooster, internist-intensivist, HMC den Haag, NVIC

dr. C.S.C. (Catherine) Bouman, internist-intensivist, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, NVIC

drs. C.V. (Carlos) Elzo Kraemer, internist-intensivist, LUMC Leiden, NVIC

dr. C.F.M. (Casper) Franssen, internist-nefroloog, UMCG Groningen, NIV

drs. A.J. (Arend-Jan) Meinders, internist-intensivist, st. Antonius Ziekenhuis, NIV

drs. K. (Koen) de Blok, internist-nefroloog-intensivist, Flevoziekenhuis Almere, NIV

drs. L. (Lea) Duijvenbode – den Dekker, IC-verpleegkundige, Amphia Ziekenhuis, V&VN

Klankbordgroep

Frans van Nynatten, renal practicioner, Amphia Ziekenhuis, V&VN

Dr. H.A. (Harmke) Polinder-Bos, Klinisch Geriater Erasmus MC, NVKG

D.M.C.T. (Daphne) Bolman, FCIC en IC connect

Dr. L. (Lilian) Vloet, Lector Acute Intensieve Zorg, FCIC en IC connect

Met ondersteuning van

drs. F.M. (Femke) Janssen, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

dr. M.S. (Matthijs) Ruiter, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Volbeda, voorzitter |

Internist-intensivist, Intensive Care Volwassenen UMCG. |

Geen |

In 2021 eenmalig betaald deelgenomen aan een digitale meeting van Baxter BV waarin nieuwe ontwikkelingen m.b.t. "blood purification" werden besproken. Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Does a novel citrate based CRRT protocol lead to improved therapy performance? Financier: Baxter. Rol: project coördinator. |

Restrictie ten aanzien van besluitvorming m.b.t. antistollingsmiddelen. Er is een vice-voorzitter aangesteld voor het bespreken van de betreffende module. |

|

Elzo Kraemer (vice-voorzitter) |

internist-intensivist, LUMC |

Lid NVIC ECLS commissie |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Meinders |

Internist-intensivist St. Antoniusziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Franssen |

Internist-nefroloog in UMCG |

Geen |

In 2021 eenmalig betaald deelgenomen aan een digitale meeting van Baxter BV waarin nieuwe ontwikkelingen m.b.t. "blood purification" werden besproken. Extern gefinancierd onderzoek: Does a novel citrate based CRRT protocol lead to improved therapy performance? Financier: Baxter. Rol: principal investigator. |

Restrictie ten aanzien van besluitvorming m.b.t. antistollingsmiddelen |

|

Bouman |

Internist-intensivist Amsterdam UMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

De Blok |

Internist-nefroloog bij Flevoziekenhuis Almere |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Duijvenbode - den Dekker |

IC-verpleegkundige |

Docent Erasmus MC academie Assessor en portfolio begeleider EVC Bestuurslid V&VN IC Bestuurslid NKIC & visiteur kwaliteitsvisitaties IC Projectlid Samen Beslissen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Klooster |

Intensivist HMC IC |

Instructeur ATLS bij stichting ALSG (betaald) docent Care Training Group (onbetaald) auteur hoofdstuk nefrologie voor Intensive Care voor de IC-verpleegkundige (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Janssen |

Junior adviseur Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Ruiter |

Senior adviseur Kennisinstituut |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door het uitvragen van knelpunten in de schriftelijke knelpunteninventarisatie bij patiëntenorganisatie Stichting Family and patient Centered Intensive Care en IC Connect (FCIC en IC Connect) en Nierpatiëntenvereniging Nederland. Het verslag hiervan (zie bijlage 2) is besproken in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. Daarnaast was een patiëntvertegenwoordiger van deze organisatie afgevaardigd in de klankbordgroep, en is de conceptrichtlijn voor commentaar voorgelegd aan FCIC en IC Connect en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn de richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Dosering |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Het betreft geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening. Er worden daarom substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor kritisch zieke patiënten met een indicatie voor nierfunctievervangende therapie. Tevens zijn schriftelijk knelpunten aangedragen door Nierpatiënten Vereniging Nederland. Een terugkoppeling hiervan is opgenomen onder bijlagen. Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.