Dosisaerosol bij longaanval astma

Uitgangsvraag

Welke toedieningsvorm van luchtwegverwijdende inhalatiemedicatie heeft de voorkeur bij volwassen patiënten met een longaanval astma die zich presenteren op de SEH?

Aanbeveling

Geef aan volwassen patiënten met een acute longaanval astma kortwerkende bronchusverwijders (beta2-agonisten, SABA, in combinatie met kortwerkende parasympaticolytica, SAMA) per inhalatie via een dosisaerosol met voorzetkamer of via verneveling.

Overweeg bronchusverwijders (SABA+ in combinatie met of afgewisseld met SAMA) in eerste instantie toe te dienen via een dosisaerosol met voorzetkamer mits hiervoor de personele en materiele randvoorwaarden aanwezig zijn. Gebruik zo mogelijk de dosisaerosol en voorzetkamer die de patiënt thuis gebruikt. Benut de opname voor goede instructie en begeleiding van inname van de bronchusverwijders.

Overweeg toediening van bronchusverwijders (SABA+SAMA) via verneveling bij ernstige benauwdheid, bij benauwdheid die lang aanhoudt of onvoldoende reageert op toediening via dosisaerosol met voorzetkamer.

Geef bij een ernstige longaanval astma de volgende doseringen:

Verneveling: 2,5–5 mg salbutamol met 0,5 mg ipratropium. Dagdosering is in de regel 4-6x daags vernevelen. Deze indicatie/dosering is overigens off-label.

Dosisaerosol:

- Berodual® (Bevat per dosis: ipratropium(bromide) 20 microg, fenoterol(hydrobromide) 50 microg.): 2 inhalaties, zo nodig na 5 min herhalen; max. 8 inhalaties per dag.

OF

- Salbutamol dosisaersol (FK, conform NHG): Dosisaerosol: 100 microg/keer in voorzetkamer; 5× inademen. Procedure na enkele minuten 4-10× herhalen.

Afwisselen met:

- Ipratropium dosisaerosol (FK, conform NHG): dosering ipratropium aerosol: 20 microg/keer in voorzetkamer; 5× inademen. Procedure na enkele minuten 2-4× herhalen.

- test

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Ten aanzien van de cruciale uitkomstmaten: verblijfduur op de SEH en het risico op ziekenhuisopname is de bewijskracht van de beschikbare literatuur als redelijk respectievelijk laag gewaardeerd, omdat de betrouwbaarheidsintervallen overlappen met de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming. De resultaten laten geen significante verschillen zien in de effectiviteit van behandeling met beta2-antagonisten tussen toediening door middel van dosisaerosolen en toediening door middel van verneveling. Voor het risico op ziekenhuisopname werd een klinisch relevant (doch statistisch niet significant) verschil van 14% gevonden in het voordeel van behandeling met dosisaerosolen.

Ook ten aanzien van de belangrijke uitkomstmaten lijkt er op basis van het bewijs uit de beschikbare literatuur geen verschil te zijn tussen de toedieningsvormen dosisaerosol en verneveling. Voor het risico op tremor werd een klinisch relevant (doch statistisch niet significant) verschil van 18% gevonden in het voordeel van behandeling met dosisaerosol. Daarnaast werd in één van de gerandomiseerde studies die geïncludeerd werden in de systematische review van Cates een kostenreductie vermeld van ongeveer 45% in het voordeel van toediening door middel van dosisaerosolen (Dhuper, 2008). De bewijskracht hiervan is echter laag, gezien het lage aantal deelnemers en de mogelijke verschillen met de Nederlandse situatie.

Voor een aantal uitkomstmaten in de categorieën symptomen en bijwerkingen is geen bewijs gevonden. Daarom zijn deze ook niet gewaardeerd met GRADE.

Het verschil in tijdsduur van de behandeling tussen toediening van dosisaerosolen en met verneveling is niet systematisch uitgewerkt in de literatuur. Dit aspect wordt wel in verhalende vorm behandeld. Het is mogelijk dat het gebruik van dosisaerosolen zorgt voor verminderde inspanning van zorgverleners en het niet meer noodzakelijkerwijs continu aanwezig zijn bij een patiënt op de SEH. Dit is echter niet verder geanalyseerd. Een groot deel van de gerandomiseerde studies is namelijk uitgevoerd met een ‘double-dummy’-design, waarbij de patiëntgroepen beide interventies krijgen toegediend, waarbij met één van de toedieningsvormen een placebo werd toegediend.

Binnen de systematische review is geen verder onderscheid gemaakt naar patiëntgroepen die meer of minder baat zouden hebben bij behandeling met dosisaerosolen en verneveling.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

In één onderzoek (Dhuper 2008) waren de kosten van toediening van bronchusverwijders via dosisaerosol significant lager (mediaan $10,11 vs $18,26, p<0.001) dan van toediening via verneveling. In dit onderzoek zijn kosten meegenomen voor medicatie/personeel/medische hulpmiddelen

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

In de klinische praktijk heeft een deel van de patiënten met een acute longaanval astma op de SEH de voorkeur aan toediening van bronchusverwijders per verneveling boven via dosisaerosol met voorzetkamer. Dit speelt met name in geval van ernstige benauwdheid, bij benauwdheid die lang aanhoudt of onvoldoende reageert op toediening via dosisaerosol met voorzetkamer. Ook kan het gevoel van superioriteit van een toedieningsvorm een rol spelen omdat op de SEH een andere behandeling wordt aangeboden dan thuis beschikbaar is. In deze gevallen kan de toediening van hoge doseringen bronchusverwijders per verneveling mogelijk voordeel bieden.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

In veel ziekenhuizen wordt traditioneel bij patiënten opgenomen voor een acute longaanval astma verneveld met kortwerkende bronchusverwijders. Echter, de geraadpleegde literatuur laat geen meerwaarde zien van verneveling boven toediening via dosisaerosol met voorzetkamer. In de systematic review van Cates uit 2013 wordt geen significant verschil gevonden tussen beide toedienroutes met betrekking tot effectiviteit en bijwerkingen. Het verschil in risico op ziekenhuisopname (-14%) en het optreden van tremor (-18%) wordt door de werkgroep als klinisch relevant beschouwd, maar is niet statistisch significant en is gebaseerd op “low grade evidence”.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Op de SEH worden patiënten met een longaanval astma vaak standaard behandeld met kortwerkende betasympathicomimetica en parasympathicolytica (SABA+SAMA) toegediend per verneveling teneinde de extreme luchtwegvernauwing te verminderen.

In de afgelopen COVID-pandemie van 2020/2021 was verneveling van medicatie gecontra-indiceerd omdat er een verhoogd risico was op besmetting met het SARS-CoV2 virus. Als alternatief werd SABA of SABA+SAMA in een dosisaerosol via een voorzetkamer geïnhaleerd, waarmee klinisch ook goede resultaten werden verkregen. Ook wordt toediening via dosisaerosol en verneveling bij kinderen reeds als equivalent beschouwd.

Uit ervaring en uit de literatuur blijkt dat bijwerkingen van deze medicatie vaker worden gezien bij vernevelingen, gebaseerd op de veel hogere dosering die dan wordt geïnhaleerd in combinatie met een hogere biologische beschikbaarheid. Toediening via een dosisaerosol in combinatie met voorzetkamer is sneller en praktischer dan via verneveling.

Conclusies

|

Moderate GRADE |

Beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation likely results in little to no difference in duration of stay at the emergency department when compared with delivery using nebulization.

Source: Cates, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation may reduce the risk of hospitalisation when compared with delivery using nebulisation.

Source: Cates, 2013 |

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation on the need for additional treatment with corticosteroids when compared with delivery using nebulisation.

Source: Cates, 2013 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation likely results in little to no difference in FEV1 when compared with delivery using nebulisation.

Source: Cates, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation may not reduce or increase respiration rate when compared with delivery using nebulisation.

Source: Cates, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation may not reduce or increase the risk of tremor as an adverse effect when compared with delivery using nebulisation.

Source: Cates, 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI to treat adult patients with an acute asthma exacerbation may reduce costs of treatment when compared with delivery using nebulisation.

Source: Dhupar, 2008 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Cates (2013) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the effect of administration of short acting beta2-agonists (in combination with short-acting muscarinic antagonists) by pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) compared to nebulization on duration of stay on the emergency department, hospitalisation, need for additional treatment, symptoms (FEV1, respiration rate, O2 saturation, coughing, wheezing, symptom scores), adverse effects (tremor, tachycardia, palpitations, nausea), and costs. They performed a systematic search up to February 2013, which resulted in the inclusion of 35 randomised controlled trials in adults and children from the age of 2 years, in whom pMDI-administered beta2-agonists were compared with we nebulisation of the same agent. 13 of these studies were of interest for this guideline, as these were performed in adults on the emergency department or outpatient setting. The total number of patients in these studies was 731. The severity of the asthma exacerbation was not reported in all study descriptions, but appeared to range from moderate to severe in the included studies that were of interest to this guideline, except for 26 patients with a mild exacerbation in Rodriguez, 1999. In general, the intervention and control groups were comparable, except for one study in which more women were included in the intervention group (Dhuper, 2008), and one study in which baseline FEV1 was lower in the intervention group (Salzman, 1989). The studies that were included in the review compared administration of beta2-agonists by pMDI combined with a spacer with wet nebulisation. The studies aimed for a similar effective dose, and described treatment protocols in enough detail. The intervention was similar between the studies: repeated dosed of the intervention were administered at specified time intervals until a specified endpoint was reached. Of the included RCTs, 6 had an open label design, and 7 were designed as a double blind double dummy study. The open design may bias the results on outcomes reported in these studies.

Results

Duration of stay in the emergency department

Two studies in the review reported on the duration of stay in the emergency department (Idris, 1993 and Rodrigo, 1993). Idris (1993) reported a shorter duration in the pMDI group (MD: -9 minutes, 95% CI -42.91 to 24.91), while Rodrigo (1993) reported a shorter duration in the nebulisation group (mean difference, MD: 15 minutes, 95% CI -22.65 to 52.65; for reference: the pMDI group had a mean duration of stay in the emergency department of 2.17 hours). As only two studies reported on this outcome, the results could not be pooled.

Hospitalisation

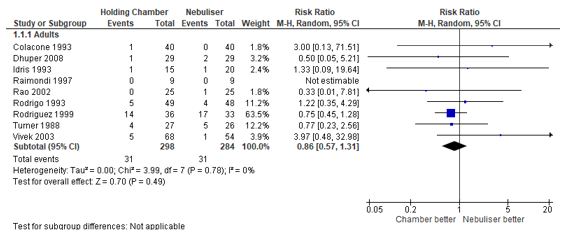

Nine studies reported on the risk of hospitalisation. No stratification was reported for ICU or ward admission. The risk of hospitalisation was 14% lower in patients treated with pMDI compared to patients treated via nebulisation, with a risk ratio of 0.86 (95% CI 0.57 to 1.31). The risk of hospitalisation was 10.4% in patients treated with pMDI. The effect was not statistically significant. See Figure 1 for the forest plot of the meta-analysis.

Figure 1 – Risk of hospitalisation after beta2-agonist treatment via pMDI chamber versus nebulisation.

CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; I2, heterogeneity; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel

Need for additional treatment

Two studies in the review reported on the probability that a patient needed additional treatment with steroids (Idris, 1993 and Turner, 1988). Idris (1993) reported a lower probability in the pMDI group (risk ratio, RR: 0.22, 95% CI 0.03 to 1.66), while Turner (1988) reported a higher probability in the pMDI group (RR: 1.93, 95% CI 0.39 to 9.63). The total number of events was 5 in the pMDI group, compared to 8 in the nebulisation group. As only two studies reported on this outcome, the results could not be pooled.

Symptoms

FEV1

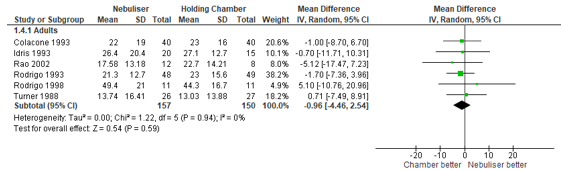

Six studies reported the final difference in FEV1. We repeated the meta-analysis with a random-effects model, and found that the final FEV1 was 0.96% lower in patients treated with nebulised beta2-agonists compared with patients treated by pMDI (95% CI: 4.46% lower to 2.54% higher) (Figure 2). The difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 2 – Final FEV1 (%) after beta2-agonist treatment via pMDI chamber versus nebulisation.

CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; I2, heterogeneity; IV, inverse variance

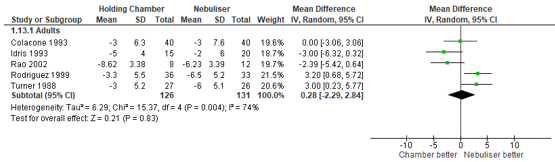

Respiration rate

The effect of treatment modality on respiratory rate was investigated in five studies. Cates (2013) reported that the respiratory rate was 0.28 breaths/minute lower in patients treated by nebuliser, compared with patients treated by pMDI (95% CI: 2.84 lower to 2.29 higher) (Figure 3). This difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 3 – Respiratory rate in breaths/minute after beta2-agonist treatment via pMDI chamber versus nebulisation.

CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; I2, heterogeneity; IV, inverse variance

O2 saturation

No studies reported on the comparison of the effects of treatment with pMDI versus nebulisation on oxygen saturation, coughing, wheezing, and symptom scores.

Adverse effects (tremor, tachycardia, palpitations, nausea)

No studies reported on tachycardia, palpitations or nausea.

Tremor

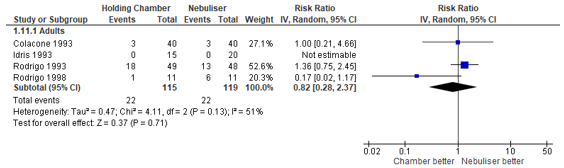

Four studies reported the risk of developing tremor subsequent to treatment with beta2-agonists by nebulisation or pMDI. The absolute risk varied between 0% and 37% between studies. Cates (2013) found a pooled relative risk of 0.82 in the advantage of the pMDI treatment (95% CI: 0.28 to 2.37). This risk ratio corresponds to a 18% lower risk of developing tremor, but the wide confidence interval indicates large uncertainty for this outcome (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Risk of developing tremor after beta2-agonist treatment via pMDI chamber versus nebulisation.

CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; I2, heterogeneity; IV, inverse variance

Cost

One study that was included in the review of Cates, 2013 reported on the cost of the compared treatments (defined as the cost of the delivery system, medication, and the respiratory therapist combined). Dhuper (2008) reported lower median costs per patient for the pMDI group, $10.11 (interquartile range: $10.03-$10.28), compared to $18.26 per patient ($9.88-$22.45) in the nebuliser group (p < 0.001).

Level of evidence of the literature

Duration of stay in the emergency department

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on the duration of stay in the emergency department in the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (systematic review of clinical trials), and was downgraded by one level for imprecision (95% confidence interval included boundary of clinical relevance): Moderate GRADE.

Hospitalisation

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on the risk of hospitalisation in the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (systematic review of clinical trials), and was downgraded by one level for inconsistency, and by one level for imprecision (95% confidence interval included boundary of clinical relevance): Low GRADE.

Need for additional treatment

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on the need for additional treatment with corticosteroids in the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (systematic review of clinical trials), and was downgraded by one level for risk of bias (no blinding), by one level for inconsistency, and by one level for imprecision (95% confidence interval included boundary of clinical relevance): Very low GRADE.

Symptoms

FEV1

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on FEV1 in the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (systematic review of clinical trials), and was downgraded by one level for imprecision (95% confidence interval included boundary of clinical relevance): Moderate GRADE.

Respiration rate

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on respiratory rate in the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (systematic review of clinical trials), and was downgraded by one level for inconsistency, and by one level for imprecision (95% confidence interval included boundary of clinical relevance): Low GRADE.

O2 saturation

No studies reported on O2 saturation: No GRADE.

Adverse effects (tremor, tachycardia, palpitations, nausea)

Tremor

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on tremor as an adverse effect of the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (systematic review of clinical trials), and was downgraded by one level for inconsistency, and by one level for imprecision (95% confidence interval included boundary of clinical relevance): Low GRADE.

Tachycardia

No studies reported on tachycardia: No GRADE.

Palpitations

No studies reported on palpitations: No GRADE.

Nausea

No studies reported on nausea: No GRADE.

Cost

The level of evidence regarding the effect of beta2-antagonists delivered by pMDI compared to nebulisation on cost of the treatment of an active asthma exacerbation started at high (randomised clinical trial), and was downgraded by one level for indirectness, and by one level for imprecision (number of patients included): Low GRADE.

Zoeken en selecteren

Om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden is er een systematische literatuuranalyse verricht naar de volgende zoekvraag (vragen):

Is toedienen van SABA of SABA+SAMA via een voorzetkamer even effectief als toedienen per verneveling in de behandeling van een longaanval astma op de spoedeisende hulp van een ziekenhuis of spoedsetting op een polikliniek.

|

P |

(Patiënten) |

= Volwassen patiënten die voor een acute astma-exacerbatie intramuraal worden behandeld met betasymapthicomimetica en parasymapthicolytica toegediend per inhalatie |

|

|

|

|

|

I |

(Interventie) |

= toediening via een dosisaërosol met voorzetkamer |

|

|

|

|

|

C |

(Comparison) |

= toediening via verneveling |

|

|

|

|

|

O |

(Outcomes) |

= verblijfsduur op de SEH, ziekenhuisopname (IC en/of afdeling), noodzaak tot aanvullende behandeling, symptomen (FEV1, ademhalingsfrequentie, zuurstofsaturatie, hoesten, piepen, symptoomscores als CAS), bijwerkingen (tremor, tachycardie, palpitaties, misselijkheid), kosten |

Relevante uitkomstmaten

De werkgroep achtte verblijfsduur op de SEH en risico op ziekenhuisopname (IC en/of afdeling) voor de besluitvorming cruciale uitkomstmaten; en noodzaak tot aanvullende behandeling, symptomen (FEV1, ademhalingsfrequentie, zuurstofsaturatie, hoesten, piepen, symptoomscores als CAS), bijwerkingen (tremor, tachycardie, palpitaties, misselijkheid) en kosten voor de besluitvorming belangrijke uitkomstmaten.

De werkgroep definieerde niet a priori de genoemde uitkomstmaten, maar hanteerde de in de studies gebruikte definities.

De werkgroep definieerde als een klinisch (patiënt) relevant verschil:

- Risico ziekenhuisopname: 5%

- Verblijfsduur: 10 min

- Astma symptomen: 10%

- Bijwerkingen: 10%

- Kosten: nvt

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 23 December 2021 The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 370 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews that included studies performed in patients with asthma, relevant for the PICO. 14 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 13 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods, mostly because these were included in the included systematic review), and 1 study was included.

Results

One study was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- <p align="left">Cates C. Spacers and nebulisers for the delivery of beta-agonists in non-life-threatening acute asthma. Respir Med. 2003 Jul;97(7):762-9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(03)00021-0. PMID: 12854625.

Evidence tabellen

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Cates, 2013

Individual study characteristics deduced from Cates 2013

PS., study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR (unless stated otherwise) |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to December 2021

A: Colacone, 1993

Study design: A: RCT

Setting and country: A: Emergency department (ED), Canada

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: not applicable (na) B: Dhuper, 2008

Study design: B: RCT

Setting and country: B: ED, New York (NJ), USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: B: Sponsored by Thayer Medical (manafacturer of holding chamber device) C: Idris, 1993

Study design: C: RCT

Setting and country: C: ED, USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: C: na D: Morley, 1988

Study design: D: RCT

Setting and country: D: Hospital inpatients, USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: D: na E: Morrone, 1990

Study design: E: RCT (crossover design, only first part used in analysis due to risk of contamination)

Setting and country: E: Mobile clinic, Brazil

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: E: na F: Raimondi, 1997

Study design: F: RCT (unblinded)

Setting and country: F: ED, Argentina

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: F: na G: Rao, 2002

Study design: G: RCT

Setting and country: G: ED, Pakistan

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: G: na H: Rodrigo, 1993

Study design: H: RCT

Setting and country: H: ED, Uruguay

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: H: na I: Rodrigo, 1998

Study design: I: RCT

Setting and country: I: ED, Uruguay

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: I: na J: Rodriguez, 1999

Study design: J: RCT

Setting and country: J: ED, Colombia

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: J: na K: Salzman, 1989

Study design: K: RCT

Setting and country: K: ED, USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: K: na L: Turner, 1988

Study design: L: RCT

Setting and country: L: ED, USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: L: na M: Vivek, 2003

Study design: M: RCT

Setting and country: M: ED, India

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: M: na |

Inclusion criteria SR: RCTs including adults and children with acute asthma, presenting in the community setting or in the emergency department, or in a in-hospital setting. Studies that also included patients with COPD were only considered if separate results were available for patients with asthma.

Exclusion criteria SR: not reported

35 studies included, of which 10 in adults. This table only reports on studies in adults

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi, ...

N, mean age A: 80; 41 (I) and 43 (C) (18 and 19) B: 60; 43 aged <30; 41 aged 30-50; 16 aged >50 (not reported) C: 35; 23 (I) and 25 (c ) (not reported) D: 28; 34.8 (I) and 31.3 (c ) (15.9 (I) and 19.0 (C )) E: 44; not reported (not reported) F: 27; not reported (not reported) G: 50; 40 (not reported) H: 97; 18 to 50 years (not reported) I: 22; 18 to 50 years (not reported) J: 69; 39 (not reported) K: 44; 32.5 (I) and 28 (C) (12.5 and 10.3) L: 53; 18 to 75 years of age (not reported) M: 122; 10 to 50 years (not reported)

Sex: A: I: not reported%; C: not reported% B: I: 17%; C: 41% C: I: not reported%; C: not reported% D: I: not reported%; C: not reported% E: I: 36 women, 8 men in total%; C: not reported% F: I: not reported%; C: not reported% G: I: not reported%; C: not reported% H: I: not reported%; C: not reported% I: I: not reported%; C: not reported% J: I: 56 women in study%; C: not reported% K: I: not reported%; C: not reported% L: I: not reported%; C: not reported% M: I: not reported%; C: not reported%

Groups comparable at baseline? A: Mean FEV1 (%predicted): I: 55% (sd: 15), C: 54% (sd: 18). Cochrane authors' comment: comparable B: more women in the intervention group C: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable D: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable E: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable F: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable G: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable H: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable I: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable J: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable K: Baseline FEV1 was lower in the intervention group L: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable M: Cochrane authors' comment: comparable |

A: 4x100 µg puffs salbutamol with 1 minute intervals inhaled by 1 slow inhalation, delivered via Aerochamber. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes until maximum bronchodilation was achieved B: 6 tidal inhalations of 90 µg salbutamol using collapsible card dual chamber spacer. Plus placebo nebulised. Once per hour up to 6 hours C: 4x90 µg puffs salbutamol with 1 minute intervals inhaled by 1 slow inhalation, delivered via Aerochamber. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes until FEV1 was 80% predicted, patient asymptomatic or up to a maximum 6 treatments D: 3 inhalations of 90 µg salbutamol with 5-minute intervals using InspirEase spacer. Repeated every 4 hours. In addition: standard IV aminophylline, IV prednisolone as recommended by Haskell et al. No oral beta2-agonists. E: 1 mg total dose (5x200µg per minute) inhaled by tidal breathing using a 500 mL spacer. F: 4x100 µg puffs salbutamol with 1 minute intervals inhaled by 3 deep inhalations, delivered via Aerochamber. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes for 2 hours, followed by hourly until 6 hours after start of therapy. In addition: 8 mg dexamethasone and oxygen. G: 4x100 µg puffs salbutamol with 1 minute intervals inhaled by 3 deep inhalations, delivered via a spacer. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes until FEV1 reached 70% predicted, or 3 doses were administered. H: 4x100 µg puffs salbutamol with 1 minute intervals inhaled by 2 deep inhalations, delivered via a volumatic spacer. Treatment was repeated every 10 minutes I: 4x100 µg puffs salbutamol with 1 minute intervals inhaled by 2 deep inhalations, delivered via a volumatic spacer. Treatment was repeated every 10 minutes J: 4x100 µg puffs salbutamol, delivered via a volumatic spacer. Treatment was repeated every 10 minutes for 1 hour. K: 3x0.65 mg puffs metaproterenol sulphate, delivered via a volumatic spacer. 5 minutes between puffs. L: 3x0.65 mg puffs metaproterenol, delivered via a volumatic spacer (Inspirease) with two slow inhalations. 2 minutes between puffs. Repeated after 30 minutes and 1 hour. In addition: oxygen and IV steroids at physicians' discretion. M: 6x0.25 mg terbutaline inhaled separately using Spacehaler. Repeated at 5 and 30 minutes or until PEFR > 250 L/min, symptoms resolved, or side effects or deterioration occurred. |

A: Nebulised salbutamol 2.5 mg in 2 mL saline by oxygen at 5 to 8 L/min. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes until maximum bronchodilation was achieved. B: 2.5mg of salbutamol nebulised. Plus placebo tidal inhalations by collapsible card dual chamber spacer. Once per hour up to 6 hours C: Nebulised salbutamol 2.5 mg in 2 mL saline by oxygen at 5 L/min. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes until FEV1 was 80% predicted, patient asymptomatic or up to a maximum 6 treatments D: 2.5 mg/0.5mL salbutamol solution in 2.0 mL saline, nebulised over 15 minutes. Flow rate not reported. Repeated every 6 hours. In addition: standard IV aminophylline, IV prednisolone as recommended by Haskell et al. No oral beta2-agonists. E: 2.5 mg/2.5mL salbutamol/saline solution driven by oxygen 6 L/min. F: 5 mg salbutamol over 5 to 10 minutes, repeated every 30 minutes for 2 hours, followed by hourly until 6 hours after start of therapy. In addition: 8 mg dexamethasone and oxygen. G: 2.5 mg/2.5mL salbutamol/saline solution driven by oxygen 5 to 6 L/min. Treatment was repeated every 30 minutes until FEV1 reached 70% predicted, or 3 doses were administered. H: 1.5 mg/4mL salbutamol/saline solution driven by oxygen 8 L/min. Treatment was repeated every 15 minutes I: 1.5 mg/4mL salbutamol/saline solution driven by oxygen 8 L/min. Treatment was repeated every 15 minutes J: 2.5 mg salbutamol solution nebulised. Treatment was repeated every 20 minutes for 1 hour K: 15 mg/2 mL metaproterenol sulphate/saline, delivered via a nebuliser over 10 minutes. L: 15 mg/2 mL metaproterenol sulphate/saline, delivered via a nebuliser over 10 minutes. Repeated after 30 minutes and 1 hour. In addition: oxygen and IV steroids at physicians' discretion. M: 5 mg/2mL terbutaline/saline nebulised. Repeated at 5 and 30 minutes or until PEFR > 250 L/min, symptoms resolved, or side effects or deterioration occurred. |

End-point of follow-up:

A: not reported B: up to discharge C: not reported D: not reported E: not reported F: not reported G: not reported H: not reported I: not reported J: not reported K: not reported L: not reported M: not reported

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I: 1 (2.5%); C: 0 (0%) B: I: 1 (3%); C: 1 (3%) C: I: 0 (0%); C: 0 (0%) D: I: 0 (0%); C: 0 (0%) E: I: 0 (0%); C: 0 (0%) F: I: 0 (0%); C: 0 (0%) G: I: not reported; C: not reported H: I: not reported; C: not reported I: I: not reported; C: not reported J: I: 0 (0%); C: 0 (0%) K: I: 6 (14%) in total study; C: see Intervention L: I: not reported; C: not reported M: I: not reported; C: not reported

|

Outcome measure-1 C: Duration in emergency department (minutes) MD: -9 (95% CI: -42.91 to 24.91) H: Duration in emergency department (minutes) MD: 15 (95% CI: -22.65 to 52.65)

Outcome measure-2 A: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 3 (95% CI: 0.13 to 71.51) B: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 0.5 (95% CI: 0.05 to 5.21) C: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 1.33 (95% CI: 0.09 to 19.64) F: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): not estimable (95% CI: na) G: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 0.33 (95% CI: 0.01 to 7.81) H: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 1.22 (95% CI: 0.35 to 4.29) J: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 0.75 (95% CI: 0.45 to 1.28) L: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 0.77 (95% CI: 0.23 to 2.56) M: Hospital admission: RR (95% CI): 3.97 (95% CI: 0.48 to 32.98) Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.94 [95% CI 0.61 to 1.43] favoring MDI Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-3 C: Need for additional steroids: RR (95% CI): 0.22 (95% CI: 0.03 to 1.66) L: Need for additional steroids: RR (95% CI): 1.93 (95% CI: 0.39 to 9.63)

Outcome measure-4 A: Final rise in FEV1 (% predicted) MD (95% CI): 1 (95% CI: -6.7 to 8.7) C: Final rise in FEV1 (% predicted) MD (95% CI): 0.7 (95% CI: -10.31 to 11.71) G: Final rise in FEV1 (% predicted) MD (95% CI): 5.12 (95% CI: -7.23 to 17.47) H: Final rise in FEV1 (% predicted) MD (95% CI): 1.7 (95% CI: -3.96 to 7.36) I: Final rise in FEV1 (% predicted) MD (95% CI): -5.1 (95% CI: -20.96 to 10.76) L: Final rise in FEV1 (% predicted) MD (95% CI): -0.71 (95% CI: -8.91 to 7.49)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 0.96 [95% CI -2.54 to 4.46] favoring MDI Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-5 A: Rise in respiratory rate (breaths per minute), MD (95% CI): 0 (95% CI: -3.06 to 3.06) C: Rise in respiratory rate (breaths per minute), MD (95% CI): -3 (95% CI: -6.32 to 0.32) G: Rise in respiratory rate (breaths per minute), MD (95% CI): -2.39 (95% CI: -5.42 to 0.64) J: Rise in respiratory rate (breaths per minute), MD (95% CI): 3.2 (95% CI: 0.68 to 5.72) L: Rise in respiratory rate (breaths per minute), MD (95% CI): 3 (95% CI: 0.23 to 5.77)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.28 [95% CI -2.29 to 2.84] favoring nebulisation Heterogeneity (I2): 73.97%

Outcome measure-6 A: Number of participants developing tremor; RR (95% CI): 1 (95% CI: 0.21 to 4.66) NA C: Number of participants developing tremor; RR (95% CI): not estimable (95% CI: not estimable) H: Number of participants developing tremor; RR (95% CI): 1.36 (95% CI: 0.75 to 2.45) I: Number of participants developing tremor; RR (95% CI): 0.17 (95% CI: 0.02 to 1.17)

Pooled effect (random effects model): 0.82 [95% CI 0.28 to 2.37] favoring MDI Heterogeneity (I2): 51.31%

No studies reported on oxygen saturation No studies reported on coughing No studies reported on wheezing No studies reported on symptom scores No studies reported on tachycardia No studies reported on palpitations No studies reported on nausea |

Facultative:

The authors of the Cochrane review found no advantage of either wet nebulisation or metered dose inhalers (MDI) combined with a spacer on time in hospital, hospital admission rates and need for additional treatment. However, MDI led to lower rates of hypoxia, pulse rates and risk of tremor.

The review selected relevant studies with regard to the outcomes of interest, and applied appropriate methods of rating study quality. The studies themselves were of reasonable quality, some applying a double-blind double dummy design, but the methods of randomisation or concealment of allocation were often unclear.

Level of evidence: GRADE (per comparison and outcome measure) including reasons for down/upgrading (extracted from Cates 2013): Duration in ED: Moderate GRADE (downgraded one level for imprecision) Hospital admission: Moderate GRADE (downgraded one level for imprecision) Need for additional steroids: K Final rise in FEV1: High GRADE (revised GRADE criteria will lead to a downgrade of 1 level due to imprecision) Rise in respiratory rate: No GRADE reported Rise in pulse rate: High GRADE reported (revised GRADE criteria will lead to a downgrade of 1 level due to imprecision) Tremor: Moderate GRADE (downgraded one level for imprecision)

A funnel plot to assess publication bias was included. |

Risk of bias tabellen

Risk of bias systematic review

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Cates, 2013 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Na |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Risk of bias randomised controlled trials

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded? Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH |

|

Colacone 1993 |

Probably yes;

Reason: Not reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: Not reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Probably yes;

Reason: Two dropouts, one in each group, intention to treat analysis was also performed |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Relevant outcomes were reported, no protocol has been published in advance |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Dhuper 2008 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Block randomization with randomisation table. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All personnel was blinded except the pharmacist. Double dummy |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; |

Probably yes;

Reason: No other problems noted other than sponsoring by manufacturer of the MDI spacer device |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Idris 1993 |

Probably yes;

Reason: no randomisation method mentioned |

Probably yes;

Reason: Nothing mentioned |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Morley 1988 |

Probably no;

Allocated one by one |

Probably no;

Investigators were aware of allocation |

Definitely no;

Open design |

Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent |

Definitely yes

Relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no;

Study of treatment after primary beta-2-agonist treatment failed, so patients already had subcutaneous or nebulised treatment |

Some concerns for all outcomes

Open design |

|

Morrone 1990 |

Probably no;

Allocated one by one |

Probably no;

Investigators were aware of allocation |

Definitely no;

Open design |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Probably no;

Only PF (%pred) reported |

Probably no;

Data measured from published graph |

Some concerns for PF (%pred) Especially open design and flawed reporting |

|

Raimondi 1997 |

Probably yes;

Not reported |

Probably yes;

Not reported |

Definitely no;

Open design |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Probably yes

Only FEV1 and hospital admission reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns In particular open design |

|

Rao 2002 |

Probably yes;

Not reported |

Probably yes;

Reason: Nothing mentioned |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably yes

FEV1 outcome calculated from SD |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Rodrigo 1993 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with randomisation table. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Nothing mentioned |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Rodrigo 1998 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with randomisation table. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Nothing mentioned |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Rodriguez 1999 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with randomisation table. |

Probably no;

Investigators were aware of allocation |

Definitely no;

Open study |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for all outcomes

Open design |

|

Salzman 1989 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with randomisation table. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Nothing mentioned |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Very likely because of double blind, double dummy design |

Probably yes

Reason: moderately low number withdrawals, unclear if the number was disproportionally distributed over the arms |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

LOW for all outcomes |

|

Turner 1988 |

Probably yes;

No randomisation method described |

Probably no;

Investigators were aware of allocation |

Definitely no;

Open study |

Definitely yes

Reason: no withdrawals |

Definitely yes

Reason: relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for all outcomes

Open design |

|

Vivek 2003 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Randomization with randomisation table. |

Probably yes;

Reason: Nothing mentioned |

Definitely no;

Open study |

Probably yes;

Not reported |

Definitely yes ;

Relevant outcomes were reported |

Definitely yes;

Reason: No other problems noted |

Some concerns for all outcomes

Open design |

Table of excluded studies

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Cates 2003 |

Covered in newer SR |

|

Colacone 1993 |

Included in SR |

|

Dhuper 2011 |

Included in SR |

|

Hendeles 2005 |

Narrative review |

|

Idris 1993 |

Included in SR |

|

Kisch 1992 |

Narrative review |

|

Raimondi 1997 |

Included in SR |

|

Rao 2002 |

Included in SR |

|

Rodrigo 1993 |

Included in SR |

|

Rodrigo 1998 |

Included in SR |

|

Salzman 1989 |

Included in SR |

|

Turner 1988 |

Included in SR |

|

Turner 1997 |

Wrong population (COPD and asthma) |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 19-02-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 19-02-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 19-02-2027

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2020 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg rondom de longaanval astma.

Samenstelling werkgroep

- Dr. E.J.M. (Els) Weersink, longarts, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam, NVALT (voorzitter)

- Drs. A. (Annelies) Beukert, longarts, Martini Ziekenhuis te Groningen, NVALT

- Dr. G.J. (Gert-Jan) Braunstahl, longarts, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland te Rotterdam, NVALT

- Drs. R.C. (Rachel) Numan, AIOS longgeneeskunde, HagaZiekenhuis te ’s Gravenhage, NVALT

- Drs. L.C. (Louise) Urlings-Strop, intensivist, Reinier de Graaf Ziekenhuis, Delft, NVIC

- Drs. F.E.C. Geijsel, SEH-artsKNMG, OLVG te Amsterdam, NVSHA

- Dr. E.C. (Erwin) Vasbinder, ziekenhuisapotheker, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland te Rotterdam, NVZA

- Prof. Dr. J.W.M. (Jean) Muris, huisarts en hoogleraar huisartsgeneeskunde, Maastricht UMC+ te Maastricht, NHG

- M.H.A. (Mariëtte) Scholma MSc, verpleegkundig specialist longziekten, Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis Assen te Assen, V&VN

- L.A.M. (Betty) Frankemölle, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Longfonds

- M.A.P. (Marjo) Poulissen, patiëntvertegenwoordiger, Longfonds

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Weersink* |

Longarts, afdeling longziekten Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam |

voorzitter RL ernstig astma (afgerond) |

In 2017 voor meerdere farmaceutische bedrijven een betaald adviseurschap. (GSK, Novartis, TEVA, Chiesi Boehringer). In 2019-2020 nog wel adviseurschap niet meer tegen betaling. 2019: dienstverlening, bijdrage aan sympsoium van Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Genzyme BV 2019: vergoeding gastvrijheid Genzyme BV.

Bestuurslid stichting RAPSODI, de stichting die de database voor ernstig astma beheerd en mede gefinancierd wordt door ZONMW, Novartis, GSK, TEVA, Astra Zeneca en Sanofi. Hier is inmiddels een governance vastgelegd welke rol de farmaceuten hierbij hebben. |

Geen actie |

|

Urlings |

Intensivist (longarts) – Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis |

Waarneming diverse ziekenhuizen Intensive Care – betaald |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vasbinder |

ziekenhuisapotheker |

Redacteur van medisch-farmaceutisch handboek “Praktische Farmacotherapie bij Longaandoeningen”, betaald door uitgever Lannoo Campus |

Betrokken bij meerdere onderzoeken bij patiënten met moeilijk behandelbaar/ernstig astma dat financieel wordt ondersteund door: * diverse zorgverzekeraars * TEVA (farmaceutische industrie) * Astra Zeneca (hoofdonderzoeker)

Geneesmiddeleninkoop voor het ziekenhuis, waaronder biologicals, verwachting dat deze binnen het kader van deze RL niet relevant zijn |

Geen actie |

|

Muris |

Universiteit Maastricht 1.0 fte Huisartspraktijk Geulle 17 werkdagen spreekuur / jaar |

Geen |

Webinar over orale corticosteroïden bij astma (GSK) |

Geen actie |

|

Geijsel |

SEH arts KNMG bij OLVG, tevens plaatsvervangend opleider en fellow opleider (95%) SEH arts bij MyEmergencyDoctor, Australische werkgever, telehealth (5%) |

EM-masterclass ontwikkelaar en faculty (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Poulissen |

Projectleider zorg Longfonds full time (met detachering voor 12 uur naar astmaVereniging Nederland en Davos). |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Beukert |

longarts te Martini Ziekenhuis Groningen tot 1-8-2021 Longarts te Deventer Ziekenhuis, Deventer, vanaf 23-8-2021 |

Secretaris Sectie Astma en Allergie (SAA) van de NVALT, onbetaald Lid werkgroep binnen SAA over biologicals, onbetaald |

Enkele keer deelname aan een betaalde adviesraadbijeenkomst (laatste in 2021, over biologicals) bij farmaceut maar dat houdt m.i. geen relatie met de inhoud van deze richtlijn |

Geen actie |

|

Numan |

AIOS longgeneeskunde HAGA ziekenhuis |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Frankemölle |

Vrijwilligster bij het Longfonds, lid van de Longfonds Ervaringsdeskundigengroep. astmaVereniging Nederland en Davos Vrijwilligster European Lung Foundation, lid van SHARP |

Ik neem deel aan diverse werkgroepen maar geen van allen heeft als hoofdthema astma-aanval. |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Braunstahl |

Longarts, Franciscus Gasthuis & Vlietland Rotterdam |

Null-aanstelling ErasmusMC voor onderzoek: onbetaald. Deelname RL ernstig astma en KNO-RL, obesitas |

Vergoeding: Presentaties en incidenteel advieswerk voor Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Novartis, GSK, AstraZeneca, ALK, MEDA en Chiesi. (wrsch speelt deze longmedicatie geen rol in deze richtlijn)

Deelname richtlijn ernstig astma Deelname klankbordgroep van het project ‘Obesitas volwassenen’

Webinar over orale corticosteroïden bij astma (GSK)

Geen vergoeding: Redactie NTvAAKI Bestuur RoLeX astma/COPD nascholingen Bestuur Rapsodi, ernstig astma database NL Voorzitter astmasectie NVALT Wetenschappelijke adviescommissie Longfonds |

Geen actie |

|

Scholma |

Verpleegkundig specialist longziekten Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis Assen |

vrijwilliger longfonds, expertgroep zorgaanpak COPD (chiesi). Geen relatie met longaanval astma voorzitter kwaliteitsteam Assen van de HZD |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntperspectief door afgevaardigde patiëntenvereniging Longfonds in de werkgroep. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan het Longfonds en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Wkkgz & Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke substantiële financiële gevolgen

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Dosisaerosol bij longaanval astma |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) niet breed toepasbaar zijn (<5.000 patiënten) en zal daarom naar verwachting geen substantiële financiële gevolgen hebben voor de collectieve uitgaven. |

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Knelpuntenanalyse en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerde de werkgroep de knelpunten in de zorg voor patiënten met een longaanval astma.

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de werkgroep concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde de werkgroep welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model. Review Manager 5.4 werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodi

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. De werkgroep heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

|

Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers |

||

|

|

||

|

|

Sterke aanbeveling |

Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling |

|

Voor patiënten |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. |

Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

|

Voor behandelaars |

De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. |

Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

|

Voor beleidsmakers |

De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. |

Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. Doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. Doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. Doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.