Bijwerkingen lange termijn gebruik PPI

Uitgangsvraag

Hoe moeten we omgaan met langdurig gebruik van protonpompremmers door volwassenen met gastro-oesofageale refluxziekte?

Aanbeveling

Continueer een PPI indien er een indicatie is voor chronisch PPI-gebruik. De bewijskracht van de resultaten over het risico op bijwerkingen van lange termijn PPI-gebruik is namelijk erg laag.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Op basis van de geïncludeerde studies zijn we onzeker over het effect van protonpompremmers (PPI’s) op alle uitkomstmaten. De bewijskracht van de gevonden resultaten is erg beperkt vanwege met name het risico op bias en imprecisie. De overall bewijskracht voor deze module is dan ook zeer laag en er is duidelijk sprake van een kennislacune.

Het is belangrijk om de voor- en nadelen van chronisch PPI-gebruik tegen elkaar af te wegen. Voordelen van chronisch PPI-gebruik bij patiënten met een gecompliceerde vorm van refluxziekte zijn dat refluxoesofagitis graad C of D of een peptische strictuur effectief wordt behandeld en dat een PPI effectiever is dan een H2-receptorantagonist in het voorkomen van een recidief (Vigneri, 1995 en Smith, 1994). In het algemeen adviseren wij een standaarddosis te gebruiken (Tabel 2). Indien er sprake is van ongecompliceerde vorm van refluxziekte, zoals patiënten zonder refluxoesofagitis of met refluxoesofagitis graad A of B, dan is het chronisch gebruik van een PPI vaak niet nodig. In een trial waarbij na een succesvolle eerste behandeling met een PPI werd gerandomiseerd naar ‘on-demand’ PPI versus placebo was 83% van de patiënten die een PPI gebruikten klachtenvrij na zes maanden en 56% van de patiënten die placebo gebruikten (Lind, 1999). Andere RCTs bevestigen dat de meerderheid van deze patiënten klachtenvrij zijn zonder chronisch PPI-gebruik of met ‘on-demand’ gebruik alleen.

Tabel 2: Overzicht standaarddosis van protonpompremmers bij patiënten met een gecompliceerde vorm van refluxziekte (NICE, 2019)

|

Protonpompremmer |

Standaarddosis |

|

Omeprazol |

1 dd 40 mg |

|

Esomeprazol |

1 dd 40 mg |

|

Lansoprazol |

1 dd 30 mg |

|

Pantoprazol |

1 dd 40 mg |

|

Rabeprazol |

1 dd 20 mg |

Een nadeel is het risico op bijwerkingen van een PPI bij chronisch gebruik. Ondanks de lange lijst aan mogelijke bijwerkingen is de bewijskracht zeer laag (Islam, 2018 en Freedberg, 2017) en is de klinische relevantie beperkt. Het absolute risico per patiënt lijkt, zeker indien er een standaarddosis wordt gebruikt, in alle gevallen laag te zijn. De expert review van de American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) door Freedberg (2017) bevestigt de bevindingen van de systematische review van Islam (2018) voor de genoemde bijwerkingen. Ook zij concluderen voor alle bovengenoemde bijwerkingen dat de bewijskracht laag tot zeer laag is, vanwege de aard van de studies (veelal observationeel), vanwege inconsistenties, verschillende vormen van bias, het ontbreken van dosis effect relatie en ‘residual confounding’ (Freedberg, 2017). Het advies wijkt voor deze bijwerkingen in de expert review van Freedberg (2017) dan ook niet af van het advies op basis van de systematische review van Islam (2018).

Overige bijwerkingen

Een aantal bijwerkingen en/of combinaties die niet in de literatuuranalyse zijn meegenomen en mogelijk tot zorgen leiden bij voorschrijvers van PPI’s worden hieronder kort behandeld:

Clopidogrel en PPI

Het is aangetoond dat omeprazol de vorming van de actieve metaboliet van clopidogrel bijna halveert door remming van het enzym CYP2C19. Deze farmacokinetische interactie gaat gepaard met een vermindering van de remming van de trombocytenaggregatie met meer dan 30% (Angiolillo, 2010). Tevens zijn er CYP2C19 polymorfismen vastgesteld die de werkzaamheid van clopidogrel beïnvloeden en mogelijk ook de kans op een interactie gemedieerd door cytochroom P-450 vergroten (Bhatt, 2009; Simon, 2009; Shuldiner, 2009; Mega, 2009 en Collet, 2009). Hoewel sommige observationele studies een interactie suggereren tussen clopidogrel en PPI’s met mogelijk een significant klinisch effect (Ho, 2009 en Juurlink, 2009), wordt deze interactie in andere studies niet gevonden (O’Donoghue, 2009 en Depta, 2010). Pantoprazol heeft een veel geringer effect op de farmacokinetiek en de trombocytenaggregatie bij gelijktijdig gebruik van clopidogrel. In de gerandomiseerde COGENT-studie blijkt echter ook omeprazol geen significante noch relevante verhoogde cardiovasculaire interactie te geven in vergelijking met placebo (Hazard ratio (HR, 95% BI): 0,99 (0,68 tot 1,44; P=-0,96). (Bhatt, 2010). Het risico op mogelijke onwerkzaamheid van clopidogrel kan vermeden worden door alternatieve therapie te overwegen.

Myocardinfarct

Er is gepostuleerd dat PPI’s het risico op een myocardinfarct vergroten door verschillende mechanismen, waaronder het veroorzaken van vasoconstrictie. In de COGENT-studie, een grote gerandomiseerde studie waarin 3761 patiënten zijn geïncludeerd met een hoog risico voor myocardinfarct, is een dergelijk effect niet vastgesteld. Van de 109 patiënten met een cardiovasculair event vond 4,9% plaats in de omeprazol groep en 5,7% in de placebogroep (HR 0,99 (95% BI): 0,68 tot 1,44; P=-0,96) (Bhatt, 2010).

Levercirrose en PPI

Aangeraden wordt om bij levercirrose het gebruik van een PPI te beperken tot patiënten met een harde indicatie, vanwege een licht verhoogd risico op spontane bacteriële peritonitis en hepatische encefalopathie (Mahmud, 2022). Vanwege de hepatische klaring wijzigt de kinetiek van PPI’s. Bij Child-Pugh C is alleen van esomeprazol aangetoond dat de kinetiek niet sterk wijzigt en daarom heeft esomeprazol 20 mg 1dd1 de voorkeur (www.geneesmiddelenbijlevercirrose.nl).

Microscopische colitis en PPI.

Een review van kleine case-control studies en case series laat een mogelijke associatie zien tussen PPI-gebruik en microscopische colitis (Law, 2017). Een case-control studie laat een OR (95% BI) zien van 7,3 (4,5 tot 12,1 (Masclee, 2015)). Er zijn echter nog geen dosis-effectstudies.

Dementie

Aangezien PPI’s in vitro een enzym blokkeren dat β-amyloid afbreekt, is gesuggereerd dat er een associatie is tussen dementie en chronisch PPI-gebruik. Een groot Duits nationaal retrospectief database onderzoek laat een associatie zien tussen chronisch PPI-gebruik en het risico op dementie (Gomm, 2016). Patiënten met comorbiditeit gebruiken in de regel ook vaker chronisch een PPI, en het is niet onaannemelijk dat de gevonden associatie tussen PPI-gebruik en dementie te verklaren valt door de bijkomende comorbiditeit bij patiënten met dementie.

Kanker

PPI-gebruik is niet geassocieerd met de ontwikkeling van maagkanker of een neuro-endocrine tumor (Attwood, 2015). Hoewel gastrine in vitro een trofisch effect heeft op dikkedarmcellen in muizen (Wang, 1996), is een verhoogd risico op dikke darmkanker in vele populatiestudies niet bevestigd (Robertson, 2007).

Staken van een PPI

Indicaties voor chronisch PPI-gebruik in het kader van refluxziekte zijn refluxoesofagitis graad C of D, een slokdarm ulcus, peptische strictuur, Barrettoesofagus en indien het de wens van de patiënt is om de medicatie te continueren vanwege het gunstig effect op klachten. Bij alle overige vormen van refluxziekte valt een tijdelijk gebruik te overwegen. Het staken van een PPI dient uitsluitend te gebeuren op basis van het ontbreken van een indicatie, niet vanwege het eventuele kleine risico op bijwerkingen. Geen enkele RCT heeft aangetoond dat patiënten die een PPI gebruiken een verhoogde incidentie hebben van aan PPI-geassocieerde bijwerkingen (Moayyedi, 2019). Echter, als er geen indicatie is om PPI te gebruiken, dan zijn ook kleine risico’s van belang. Indien besloten wordt om de PPI-behandeling te staken, dan is het van belang om de patiënt voor te lichten over leefstijl- en voedingsadviezen. Zie hiervoor module leefstijl- en voedingsadviezen.

Oudere patiënten en PPI

De prevalentie van PPI-gebruik onder oudere patiënten (mensen ≥ 70 jaar) is verhoogd en meerdere studies hebben aangetoond dat de indicatie nogal eens ontbreekt (Pottegard, 2016; Daniels, 2020; Bustillos, 2018; Lassalle, 2020 en Rotman, 2013). De incidentie van bijwerkingen zoals diarree, verminderde vitamine B12-opname, hypomagnesemie, maagdarminfecties en heupfracturen is weliswaar laag, maar oudere patiënten hebben een groter risico op deze bijwerkingen (Farrell, 2017). Overwegingen voor het continueren, minderen of stoppen van PPI’s bij mensen ≥70 jaar die chronisch PPI’s gebruiken in de context van de behandeling van maagklachten, preventie van maagcomplicaties en bijwerkingen wordt beschreven in het kennisdocument Minderen en Stoppen van Protonpompremmers behorende bij de multidisciplinaire richtlijn Polyfarmacie bij Ouderen.

Mensen met een verstandelijke beperking en PPI

De prevalentie van gastro-oesofageale refluxziekte (GORZ) onder geïnstitutionaliseerde mensen met een verstandelijke beperking bedraagt ongeveer 50%, waarbij 70% van deze refluxpatiënten endoscopisch vastgestelde refluxoesofagitis heeft (Böhmer, 2000). Bij symptomen als hematemese, rumineren, gedragsverandering, het weigeren van voedsel of tanderosie is er een verhoogd risico op GORZ. Ook bij mensen met een verstandelijke beperking is de behandeling met een PPI zeer effectief. Adviezen omtrent bijwerkingen van PPI’s bij mensen met een verstandelijke beperking verschillen niet van de adviezen voor mensen met geen verstandelijke beperking.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten met refluxziekte kunnen PPI’s een positief effect hebben op de symptomen en hun kwaliteit van leven. Het bewijs voor bijwerkingen van PPI’s is beperkt. Echter, zorgen over bijwerkingen bij patiënten kunnen leiden tot onnodig staken van deze medicatie, vaak zonder overleg met de voorschrijver (Kurlander, 2019). Goede voorlichting vooraf over werking en de kans op bijwerkingen kan de patiënt helpen de juiste afweging te maken. Op de website apotheek.nl is betrouwbare informatie te vinden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van PPI’s zijn in het algemeen laag (www.medicijnkosten.nl).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Overwegingen omtrent aanvaarbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie spelen geen rol bij de huidige aanbeveling.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Een PPI is een effectieve behandeling voor patiënten met GORZ. Ondanks dat er veel studies rapporteren over bijwerkingen van PPI’s is het bewijs hiervoor erg beperkt. Voor de patiënten met een juiste indicatie voor PPI-gebruik wegen de voordelen van PPI-gebruik op tegen de (potentiële) nadelen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Protonpompremmers (PPI’s) zijn effectief voor de behandeling van gastro-oesofageale refluxziekte (GORZ) en geneesmiddelen die veel worden voorgeschreven. Deze medicatie wordt vaak chronisch gebruikt en de indicatie staat nogal eens ter discussie. De laatste jaren is er steeds meer aandacht voor een scala aan gerapporteerde bijwerkingen. Echter, voor vele vermeende bijwerkingen is een direct causaal verband niet aangetoond, en de klinische relevantie van de meeste bijwerkingen lijkt beperkt. De aandacht voor deze bijwerkingen is de laatste tijd groot geweest wat heeft gezorgd voor nogal wat onrust bij zowel voorschrijvers als bij patiënten.

Conclusies

Pneumonia

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure pneumonia compared with no PPI use in adult patients.

Source: Islam, 2018 |

Hip fracture

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure hip fracture compared with no PPI use in adult patients.

Source: Islam, 2018 |

Kidney disease

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure kidney disease compared with no PPI use in adult patients.

Source: Islam, 2018 |

Vitamin B12 deficiency

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure vitamin B12 deficiency compared with no PPI use in adult patients.

Source: Islam, 2018 |

Hypomagnesemia

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure hypomagnesemia compared with no PPI use in adult patients.

Source: Islam, 2018 |

Infectious enterocolitis

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure infectious enterocolitis compared with placebo in adult patients with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease.

Source: Moayyedi, 2019 |

Clostridium difficile infection

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure clostridium difficile infection compared with placebo in adult patients with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease.

Source: Moayyedi, 2019 |

Iron deficiency

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of PPIs on the outcome measure iron deficiency compared with no PPI use in adult patients.

Source: Attwood, 2015 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

The data of the systematic review of Islam (2018) were used to analyze the results on the outcome measures pneumonia, hip fracture, kidney disease, hypomagnesemia and vitamin B12 deficiency. The other individual studies (Attwood, 2015 and Moayyedi, 2019) were used to describe the results on the outcome measures clostridium difficile infection, infectious enterocolitis and iron deficiency.

Systematic review

Islam (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the possible association between the use of PPIs and long-term adverse effects. Databases that were used for the literature search, included Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Database of Systematic Reviews. Only studies that evaluated the adverse effects of PPI use over at least a three-month period, were included. A total of 43 studies (32 case-control, eight cohort and three cross-sectional studies) were included in the systematic review, almost all conducted in industrialized countries. Quality of the studies was assessed using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Study outcomes included hip fracture, community acquired pneumonia, colorectal, pancreatic and gastric cancer, kidney disease, cardiac disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, Alzheimer’s disease and hypomagnesemia. Of all included studies in the systematic review, 16 studies were not included in the meta-analysis due to inadequate methods (high risk of bias) or overlapping study populations. For our literature analysis, five studies were further excluded (see exclusion table) due to inclusion of children (Freedberg, 2015), missing data on the number of patients in the control group (Luk, 2013) or cross-sectional designs (Kieboom, 2015; Markovits, 2014; Lindner, 2014), giving a total of 22 relevant individual studies. In these studies, mean or median age ranged from 51-82 years, although some studies only reported the proportion of patients aged ≥ 60 years. Proportion of males ranged from 18-53%, with two studies including (almost) exclusively males (Adam, 2014 and Hermos, 2012). Length of follow-up ranged from three months to ten years, although this was not reported in all studies (N=8).

Individual studies

Moayyedi (2019) performed a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which they evaluate the efficacy and safety of long-term use of PPIs. This study was part of the Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies (COMPASS) trial, in which patients with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease were randomized to either rivaroxaban, aspirin or rivaroxaban + aspirin. Patients who were not already taking PPI at baseline, were randomized to receive pantoprazole (40 mg once daily, N=8791) or placebo (once daily, N= 8807). Mean age was 67.6 years and 78% of the participants was male. In total, 23% and 2.6% of the participants was respectively current smoker or had a history of a peptic ulcer. Follow-up was three years. Respectively 21% and 22% of the participants in the pantoprazole-group and placebo-group discontinued study medication permanently during the trial period.

Attwood (2015) evaluated the safety of long-term use of PPIs in patients that participated in the SOPRAN-trial and the LOTUS-trial. Both trials were multicenter, open-label randomized trials. Details on both trials are described separately:

SOPRAN-trial

In the SOPRAN-trial patients with chronic gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and reflux esophagitis were randomized to treatment with omeprazole (20 mg or adjusted to 40 mg once daily and then 20 mg twice daily if required, N=155) or open anti-reflux surgery (ARS, N=155). Follow-up period was 12 years. Median age was 54 years in the omeprazole-group, compared to 50 years in the ARS-group. In the omeprazole-group, 75% of the participants were male, compared to 77% in the ARS-group.

LOTUS-trial

In the LOTUS-trial patients with chronic GERD were randomized to treatment with esomeprazole (20 mg or 40 mg once daily, N=266) or laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery (ARS, N=288). Follow-up period was seven years. Median age was 46 years in the esomeprazole-group, compared to 44 years in the ARS-group. In the esomeprazole-group, 75% of the participants were male, compared to 69% in the ARS-group.

Results

Pneumonia

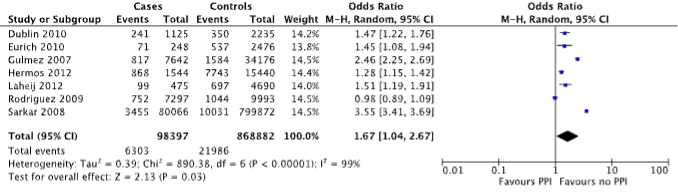

Seven case-control studies reported on the outcome measure pneumonia (Dublin, 2010; Eurich, 2010; Gulmez, 2007; Hermos, 2012; Laheij, 2012; Rodriguez, 2009 and Sarkar, 2008), which was defined as community-acquired pneumonia. A total of 6,303/98,397 (6.4%) patients with pneumonia were PPI users, compared to 21,986/868,882 (2.5%) of controls (Figure 1). The corresponding odds ratio (OR, 95%CI) is 1.67 (1.04 to 2.67), in favor of no PPI use. This is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 1. Forest plot of the comparison between patients with pneumonia and controls by means of PPI use (Islam, 2018).

Hip fracture

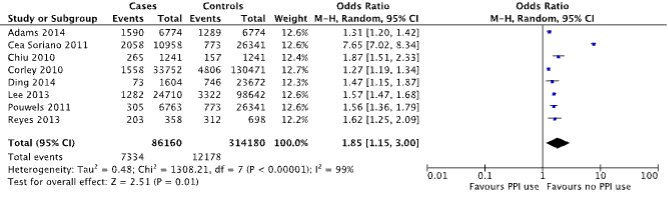

Eight case-control studies reported on the outcome measure hip fracture (Adams, 2014; Cea Soriano; Chiu, 2010; Corley, 2010; Ding, 2014; Lee, 2013; Pouwels, 2011 and Reyes, 2013). A total of 7,334/86,160 (8.5%) patients with hip fracture were PPI users, compared to 12,178/314,180 (3.9%) of controls (Figure 2). The corresponding OR (95%CI) is 1.85 (1.15 to 3.00), in favor of no PPI use. This is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 2. Forest plot of the comparison between patients with hip fracture and controls by means of PPI use (Islam, 2018).

Kidney disease

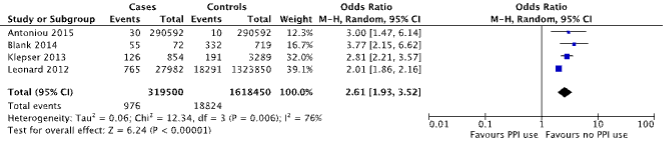

Three case-control studies and one cohort study reported on the outcome measure kidney disease (Antoniou, 2015; Blank, 2014; Klepser, 2013 and Leonard, 2012), which was defined as acute kidney injury. A total of 976/319,500 (0.3%) patients with kidney disease were PPI users, compared to 18,824/1618,450 (1.1%) of controls (Figure 3). The corresponding OR (95%CI) is 2.61 (1.93 to 3.52), in favor of no PPI use. This is considered clinically relevant.

Figure 3. Forest plot of the comparison between patients with kidney disease and controls by means of PPI use (Islam, 2018).

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Two case-control studies reported on the outcome measure vitamin B12 deficiency (Valuck, 2004 and Lam, 2013). For this outcome measure, data from the individual studies was used. Valuck (2004) reported on vitamin B12 deficiency as a serum level of less than 130 mg/mL or when methylmalonic acid (MMA) and homocysteine (HCYS) were elevated (in combination with a low-normal vitamin B12 serum levels of 130 to 300 mg/mL). A total of 16/53 (30.1%) patients with vitamin B12 deficiency were current PPI users, compared to 42/212 (19.9%) of controls. The corresponding OR (95%CI) is 1.75 (0.89 to 3.44), in favor of no PPI use. This is considered clinically relevant.

Lam (2013) reported on vitamin B12 deficiency as defined by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or with abnormally low serum values of B12 (not defined) or with injections with vitamin B12 for at least six months. A total of 3,120/25,956 (12%) patients with vitamin B12 deficiency were current PPI users, compared to 13,210/184,199 (7.2%) of controls. The corresponding OR (95%CI) is 1.77 (1.70 to 1.84), in favor of no PPI use. This is considered clinically relevant.

Hypomagnesemia

One individual case-control study reported on the outcome measure hypomagnesemia (Zipursky, 2014). For this outcome measure, data from the individual study was used. Hypomagnesemia was defined as hypomagnesemia or magnesium deficiency according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). However, only patients who were hospitalized were considered. A total of 143/366 (39.1%) patients with hypomagnesemia were current PPI users (used within the past 90 days), compared to 305/1,464 (20.8%) of controls. The corresponding (adjusted) OR (95%CI) is 1.43 (1.06 to 1.93), in favor of no PPI use. This is considered clinically relevant.

Infectious enterocolitis

One trial reported on the outcome measure infectious enterocolitis (Moayyedi, 2019). Infectious enterocolitis was defined as other enteric infections (not further specified). In the pantoprazole-group, 119/8791 (1.4%) participants had an enteric infection, compared to 90/8,807 (1%) in the placebo-group. The corresponding OR (95%CI) is 1.33 (1.01 to 1.75), in favor of the placebo-group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Clostridium difficile infection

One trial reported on the outcome measure clostridium difficile infection (CDI, Moayyedi, 2019). In the pantoprazole-group, 9/8,791 (0.1%) participants had a CDI, compared to 4/8,807 (<0.1%) in the placebo-group. The corresponding OR (95%CI) is 2.26 (0.70 to 7.34), in favor of the placebo-group. This difference is considered clinically relevant.

Iron deficiency

None of the included studies reported on the outcome measure iron deficiency. However, one study reported on the outcome measures ferritin and iron-binding capacity (Attwood, 2015), which are both related to iron deficiency. Therefore, it was decided to analyze those (indirect) results in the literature analysis.

Ferritin

Results of the SOPRAN-trial and LOTUS-trial (Attwood, 2015) are described in Table 1. After five years of follow-up, ferritin levels are 79 µg/L in the PPI-group and 80 µg/L in the surgery group of the SOPRAN-trial (SDs not reported). This corresponds to a mean difference of 1, in favor of the surgery-group. Five-year follow-up ferritin levels are 156 µg/L in the PPI-group of the LOTUS-trial, compared to 122 µg/L in the surgery-group. This corresponds to a mean difference of 34 µg/L, in favor of the PPI-group. The standardized mean difference could not be calculated since SDs are not reported.

Iron-binding capacity

Results of the LOTUS-trial (Attwood, 2015) are described in Table 1. After five years of follow-up, iron-binding capacity was 55.1 µmol/L in the PPI-group and 56.7 µmol/L in the surgery-group (SDs not reported). This corresponds to a mean difference of 1.6, in favor of the surgery-group. The standardized mean difference could not be calculated since SDs are not reported.

Table 4: The effect of proton pump inhibitors on ferritin (µg/L) and iron-binding capacity (µmol/L) in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease, randomized to (es)omeprazole or (open/laparoscopic)anti-reflux surgery, using data of the SOPRAN-trial and the LOTUS-trial (Attwood, 2015).

|

|

SOPRAN-trial |

LOTUS-trial |

|||||||||

|

|

N |

Baseline |

1 year |

3 years |

5 years |

|

Baseline |

1 year |

3 years |

5 years |

|

|

Ferritin (µg/L) |

|

|

|||||||||

|

PPI-group |

93-111 |

70 |

71 |

67 |

79 |

180-265 |

118 |

131 |

133 |

156 |

|

|

Surgery |

84-103 |

92 |

66 |

55 |

80 |

158-245 |

111 |

109 |

120 |

122 |

|

|

Iron-binding capacity (µmol/L) |

|

|

|||||||||

|

PPI-group |

- |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

179-265 |

53.9 |

54.4 |

53.0 |

55.1 |

|

|

Surgery |

- |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

157-245 |

55.0 |

55.7 |

53.5 |

56.7 |

|

PPI=proton pump inhibitors, NA=not assessed.

Level of evidence of the literature

Pneumonia

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure pneumonia comes from observational studies and therefore started at low certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias (risk of residual confounding, downgraded one level) and the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the upper boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Hip fracture

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hip fracture comes from observational studies and therefore started at low certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias (missing data not reported for several studies, risk of residual confounding, downgraded one level) and the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the upper boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Kidney disease

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure kidney disease comes from observational studies and therefore started at low certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias (missing data not reported for several studies, risk of residual confounding, downgraded one level).

Vitamin B12 deficiency

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure vitamin B12 deficiency comes from observational studies and therefore started at low certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias (missing data not reported for one large study, risk of residual confounding, downgraded one level).

Hypomagnesemia

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure hypomagnesemia comes from an observational study and therefore started at low certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was high risk of bias (missing data and length of follow-up not reported, risk of residual confounding, downgraded one level) and the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the upper boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded one level).

Infectious enterocolitis

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure infectious enterocolitis comes from a RCT and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (risk on misclassification, downgraded one level) and the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the upper boundary of clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded one level). Finally, study population consists of elderly with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease (indirectness, downgraded one level). Although, several employees of the sponsor were actively involved (e.g. study design, interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript), the level of evidence was not further downgraded because it does not seem to have had an influence on the results.

Clostridium difficile infection

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure infectious enterocolitis comes from a RCT and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (risk on misclassification, downgraded one level). Furthermore, the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded two levels). Finally, study population consists of elderly with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease (indirectness, downgraded one level). Although, several employees of the sponsor were actively involved (e.g. study design, interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript), the level of evidence was not further downgraded because it does not seem to have had an influence on the results.

Iron deficiency

RCT

The level of evidence regarding the outcome measure iron deficiency comes from RCTs and therefore started at high certainty. The level of evidence was downgraded to very low. There was risk of bias (open-label trial, unclear allocation sequence and concealment, downgraded two levels) and the effect estimate (95%CI) crossed the boundaries of clinical relevance (imprecision, downgraded two levels). Furthermore, the outcome measures are indirect (indirectness, downgraded one level). Although, several employees of the sponsor were actively involved (e.g. study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript), the level of evidence was not further downgraded because it does not seem to have had an influence on the results.

Zoeken en selecteren

Two different literature searches were performed. At first we searched for systematic reviews. After this we performed an additional search to supplement the selected review(s) with studies on outcome measures that were not addressed in the systematic reviews.

The first step was a systematic review of the literature to answer the following question: What are the adverse outcomes on the long-term in adults using proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)?

P (Patients) adults using PPIs

O (Outcomes) adverse outcomes

The results of the first search were initially used to create an overview of adverse outcomes which possibly could be related to the long-term use of PPIs. Based on this overview, the working group selected eight adverse outcomes that needed to be addressed in the systematic literature analysis.

Besides, the results of this first search were used to identify systematic reviews that analyze results on those eight adverse outcomes. Five outcome measures (i.e. pneumonia, hip fracture, kidney disease, vitamin B12 deficiency and hypomagnesemia) were addressed in one of the systematic reviews (Islam, 2018). Therefore, a second search was performed to find information on the three outcome measures (i.e. infectious enterocolitis, clostridium difficile infection and iron deficiency) that were not addressed in this systematic review.

The second step was a systematic review of the literature to answer the following question, in order to supplement data in the selected systematic review:

What are the effects of long-term use of PPIs on the outcome measures infectious enterocolitis, clostridium difficile infection and iron deficiency?

P (Patients) adults using PPIs

I (Intervention) PPIs

C (Comparison) no PPIs

O (Outcomes) adverse outcomes (infectious enterocolitis, clostridium difficile infection and iron deficiency)

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group decided not to differentiate between the different adverse outcomes and therefore considered all outcome measures as important for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

For all outcome measures, the default thresholds proposed by the international GRADE working group were used as a threshold for clinically relevant differences: a 25% difference in relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes (RR< 0.8 or RR> 1.25), and 0.5 standard deviations (SD) for continuous outcomes.

Search and select (Methods)

Two different literature searches were performed. At first we searched for systematic reviews. After this we performed an additional search to supplement the selected review with studies on outcome measures that were not addressed in the systematic review.

Search 1: systematic reviews

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until July 19th 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 98 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: systematic reviews with meta-analysis evaluating the adverse effects of long-term use of PPI’s (i.e. > eight weeks). 30 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 29 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and one study was included (Islam, 2018).

Search 2: observational studies

Since the study of Islam (2018) did not report on the outcome measures infectious enterocolitis, clostridium difficile infection and iron deficiency, a second search was performed. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until September 5th 2023. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 1942 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria: comparative studies on the effects of long-term use of PPIs (i.e. > eight weeks) in adults on the outcome measures infectious enterocolitis, clostridium difficile infection and iron deficiency. Ten studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, eight studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included (Attwood, 2015 and Moayyedi, 2019).

Results

One systematic review with 22 relevant studies (Islam, 2018), and two additional studies were included in the analysis of the literature (Attwood, 2015 and Moayyedi, 2019). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Angiolillo DJ, Gibson CM, Cheng S, Ollier C, Nicolas O, Bergougnan L, Perrin L, LaCreta FP, Hurbin F, Dubar M. Differential effects of omeprazole and pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel in healthy subjects: randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover comparison studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jan;89(1):65-74. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.219. Epub 2010 Sep 15. PMID: 20844485.

- Attwood SE, Ell C, Galmiche JP, Fiocca R, Hatlebakk JG, Hasselgren B, Långström G, Jahreskog M, Eklund S, Lind T, Lundell L. Long-term safety of proton pump inhibitor therapy assessed under controlled, randomised clinical trial conditions: data from the SOPRAN and LOTUS studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Jun;41(11):1162-74. doi: 10.1111/apt.13194. Epub 2015 Apr 10. PMID: 25858519.

- Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, Cohen M, Lanas A, Schnitzer TJ, Shook TL, Lapuerta P, Goldsmith MA, Laine L, Scirica BM, Murphy SA, Cannon CP; COGENT Investigators. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Nov 11;363(20):1909-17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007964. Epub 2010 Oct 6. PMID: 20925534.

- Bhatt DL. Tailoring antiplatelet therapy based on pharmacogenomics: how well do the data fit? JAMA. 2009 Aug 26;302(8):896-7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1249. PMID: 19706866.

- Böhmer CJ, Klinkenberg-Knol EC, Niezen-de Boer MC, Meuwissen SG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in intellectually disabled individuals: how often, how serious, how manageable? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Aug;95(8):1868-72. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02238.x. PMID: 10950028.

- Bustillos H, Leer K, Kitten A, Reveles KR. A cross-sectional study of national outpatient gastric acid suppressant prescribing in the United States between 2009 and 2015. PLoS One. 2018 Nov 30;13(11):e0208461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208461. PMID: 30500865; PMCID: PMC6267968.

- Collet JP, Hulot JS, Pena A, Villard E, Esteve JB, Silvain J, Payot L, Brugier D, Cayla G, Beygui F, Bensimon G, Funck-Brentano C, Montalescot G. Cytochrome P450 2C19 polymorphism in young patients treated with clopidogrel after myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Lancet. 2009 Jan 24;373(9660):309-17. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61845-0. Epub 2008 Dec 26. PMID: 19108880.

- Daniels B, Pearson SA, Buckley NA, Bruno C, Zoega H. Long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors: whole-of-population patterns in Australia 2013-2016. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020 Mar 19;13:1756284820913743. doi: 10.1177/1756284820913743. PMID: 32218806; PMCID: PMC7082869.

- Depta JP, Bhatt DL. Omeprazole and clopidogrel: Should clinicians be worried? Cleve Clin J Med. 2010 Feb;77(2):113-6. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09173. PMID: 20124268.

- Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, Boghossian T, Pizzola L, Rashid FJ, Rojas-Fernandez C, Walsh K, Welch V, Moayyedi P. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2017 May;63(5):354-364. PMID: 28500192; PMCID: PMC5429051.

- Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The Risks and Benefits of Long-term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017 Mar;152(4):706-715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031. PMID: 28257716.

- Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, Broich K, Maier W, Fink A, Doblhammer G, Haenisch B. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitors With Risk of Dementia: A Pharmacoepidemiological Claims Data Analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Apr;73(4):410-6. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791. PMID: 26882076.

- Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, Rumsfeld JS. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009 Mar 4;301(9):937-44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261. PMID: 19258584.

- Islam MM, Poly TN, Walther BA, Dubey NK, Anggraini Ningrum DN, Shabbir SA, Jack Li YC. Adverse outcomes of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Dec;30(12):1395-1405. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001198. PMID: 30028775.

- Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, Szmitko PE, Austin PC, Tu JV, Henry DA, Kopp A, Mamdani MM. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009 Mar 31;180(7):713-8. Doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. Epub 2009 Jan 28. PMID: 19176635; PMCID: PMC2659819.

- Kurlander JE, Kennedy JK, Rubenstein JH, Richardson CR, Krein SL, De Vries R, Saini SD. Patients' Perceptions of Proton Pump Inhibitor Risks and Attempts at Discontinuation: A National Survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb;114(2):244-249. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000061. PMID: 30694867.

- Lassalle M, Le Tri T, Bardou M, Biour M, Kirchgesner J, Rouby F, Dumarcet N, Zureik M, Dray-Spira R. Use of proton pump inhibitors in adults in France: a nationwide drug utilization study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020 Mar;76(3):449-457. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02810-1. Epub 2019 Dec 14. PMID: 31838548.

- Law EH, Badowski M, Hung YT, Weems K, Sanchez A, Lee TA. Association Between Proton Pump Inhibitors and Microscopic Colitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2017 Mar;51(3):253-263. doi: 10.1177/1060028016673859. Epub 2016 Oct 13. PMID: 27733667.

- Lind T, Havelund T, Lundell L, Glise H, Lauritsen K, Pedersen SA, Anker-Hansen O, Stubberöd A, Eriksson G, Carlsson R, Junghard O. On demand therapy with omeprazole for the long-term management of patients with heartburn without oesophagitis--a placebo-controlled randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999 Jul;13(7):907-14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00564.x. PMID: 10383525.

- Masclee GM, Coloma PM, Kuipers EJ, Sturkenboom MC. Increased risk of microscopic colitis with use of proton pump inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 May;110(5):749-59. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.119. Epub 2015 Apr 28. PMID: 25916221.

- Mahmud N, Serper M, Taddei TH, Kaplan DE. The Association Between Proton Pump Inhibitor Exposure and Key Liver-Related Outcomes in Patients With Cirrhosis: A Veterans Affairs Cohort Study. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul;163(1):257-269.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.052. Epub 2022 Apr 6. PMID: 35398042; PMCID: PMC10020994.

- Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, Connolly SJ, Dyal L, Shestakovska O, Leong D, Anand SS, Störk S, Branch KRH, Bhatt DL, Verhamme PB, O'Donnell M, Maggioni AP, Lonn EM, Piegas LS, Ertl G, Keltai M, Bruns NC, Muehlhofer E, Dagenais GR, Kim JH, Hori M, Steg PG, Hart RG, Diaz R, Alings M, Widimsky P, Avezum A, Probstfield J, Zhu J, Liang Y, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Kakkar AK, Parkhomenko AN, Ryden L, Pogosova N, Dans AL, Lanas F, Commerford PJ, Torp-Pedersen C, Guzik TJ, Vinereanu D, Tonkin AM, Lewis BS, Felix C, Yusoff K, Metsarinne KP, Fox KAA, Yusuf S; COMPASS Investigators. Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitors Based on a Large, Multi-Year, Randomized Trial of Patients Receiving Rivaroxaban or Aspirin. Gastroenterology. 2019 Sep;157(3):682-691.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056. Epub 2019 May 29. PMID: 31152740.

- Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias W, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 22;360(4):354-62. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. Epub 2008 Dec 22. PMID: 19106084.

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019 Oct. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 184.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552570/

- O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, Michelson AD, Hautvast RW, Ver Lee PN, Close SL, Shen L, Mega JL, Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009 Sep 19;374(9694):989-997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61525-7. Epub 2009 Aug 31. PMID: 19726078.

- Pottegård A, Broe A, Hallas J, de Muckadell OB, Lassen AT, Lødrup AB. Use of proton-pump inhibitors among adults: a Danish nationwide drug utilization study. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016 Sep;9(5):671-8. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16650156. Epub 2016 May 26. PMID: 27582879; PMCID: PMC4984329.

- Robertson DJ, Larsson H, Friis S, Pedersen L, Baron JA, Sørensen HT. Proton pump inhibitor use and risk of colorectal cancer: a population-based, case-control study. Gastroenterology. 2007 Sep;133(3):755-60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.014. Epub 2007 Jun 20. PMID: 17678921.

- Rotman SR, Bishop TF. Proton pump inhibitor use in the U.S. ambulatory setting, 2002-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056060. Epub 2013 Feb 13. PMID: 23418510; PMCID: PMC3572154.

- Shuldiner AR, O'Connell JR, Bliden KP, Gandhi A, Ryan K, Horenstein RB, Damcott CM, Pakyz R, Tantry US, Gibson Q, Pollin TI, Post W, Parsa A, Mitchell BD, Faraday N, Herzog W, Gurbel PA. Association of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype with the antiplatelet effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy. JAMA. 2009 Aug 26;302(8):849-57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1232. PMID: 19706858; PMCID: PMC3641569.

- Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Méneveau N, Steg PG, Ferrières J, Danchin N, Becquemont L; French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) Investigators. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jan 22; 360(4):363-75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. Epub 2008 Dec 22. PMID: 19106083.

- Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R, Ross BA, Bate CM, Brown P, Dronfield MW, Green JR, Hislop WS, Theodossi A, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign esophageal stricture. Restore Investigator Group. Gastroenterology. 1994 Nov;107(5):1312-8. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90532-0. PMID: 7926495.

- Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, Di Mario F, Battaglia G, Mela GS, Pilotto A, et al. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995 Oct 26;333(17):1106-10. Doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510263331703. PMID: 7565948.

- Wang TC, Koh TJ, Varro A, Cahill RJ, Dangler CA, Fox JG, Dockray GJ. Processing and proliferative effects of human progastrin in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996 Oct 15;98(8):1918-29. doi: 10.1172/JCI118993. PMID: 8878444; PMCID: PMC507632.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question: What are the unfavourable effects of long-term use of PPI’s?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Islam, 2018

[individual study characteristics deduced from [Islam, 2018 ]]

|

SR and meta-analysis of cohort/case-control and cross-sectional studies

Literature search up to [July/2016]

A: Sarkar, 2008 B: Rodrigiuez, 2009 C: Laheij, 2012 D: Hermos, 2012 E: Gulmez, 2007 F: Eurich, 2010 G: Dublin, 2010 H: Adams, 2014 I: Reyes, 2013 J: Corley, 2010 K: Chiu, 2010 L: Ding, 2014 M: Lee, 2013 N: Cea Soriano, 2011 O: Pouwels, 2011 P: Leonard, 2012 Q: Klepser, 2013 R: Blank, 2014 S: Antoniou, 2015 T: Valuck, 2004 U: Lam, 2013 V: Zipursky, 2014

Study design: RCT [parallel / cross-over], cohort [prospective / retrospective], case-control

Cohort: S Case-control: A-R, T-V

Setting and Country: A: United Kingdom B: Sweden C: Netherlands D: United States E: Denmark F: Canada G: United States H: United States I: Spain J: United States K: United Kingdom K: Taiwan L: United States M: South Korea N: United Kingdom O: Netherlands P: United Kingdom Q: United States R: New Zealand S: Canada T: United States U: United States V: Canada

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest. Funding source not reported. |

Inclusion criteria SR: Observational studies reporting relevant risk and adverse events of use of PPIs compared to non-PPI users.

Exclusion criteria SR: Case-reports, editorials, reviews, clinical trials, studies without ORs or HRs (or when unable to calculate) or adverse events as outcome measure. Studies with exposure to PPIs of ≤ 3 months, patients aged ≤ 18 years.

Total of 43 studies included, of which 22 studies are relevant and reported in this table.

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

Studies vary widely with respect to age and sex ratio. Study groups within studies are largely similar, although mean age in the intervention group is significantly higher in study of Sarkar (2008). |

Use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) for at least 3 months.

|

No use of PPIs

|

End-point of follow-up:

|

Effect measures: OR, HR [95%CI]

Pneumonia A: OR 3.55 [3.41 to 3.69] B: OR 1.16 [1.03 to 1.31] C: OR 1.98 [1.36 to 2.62] D: OR 1.29 [1.15 to 1.45] E: OR 2.46 [2.25 to 2.69] F: OR 1.45 [1.08 to 1.94] G: OR 1.47 [1.22 to 1.76] Total effect estimate: OR 1.67 [1.04 to 2.67]

Hip fracture H: OR 1.31 [1.20 to 1.42] I: OR 1.44 [1.09 to 1.89] J: OR 1.27 [1.19 to 1.34] K: OR 1.87 [1.51 to 2.33] L: HR 1.47 [1.15 to 1.87] M: OR 1.34[1.24 to 1.44] N: OR 1.31 [1.28 to 1.33] O: OR 1.56[1.41 to 1.86] Total effect estimate: OR 1.42 [1.33 to 1.53]

Kidney disease P: OR 2.01 [1.86 to 2.16] Q: OR 1.72 [1.27 to 2.32] R: OR 3.77 [2.15 to 6.62] S: HR 3.00 [1.47 to 6.14] Total effect estimate: OR 2.61 [1.93 to 2.25]

Vitamin B12 deficiency T: OR 4.45 [1.47 to 13.34] U: OR 1.25 [1.17 to 1.34]

Hypomagnesia V: OR 1.43 [1.06 to 1.93]

|

Study authors report Although the study authors point out the significant statistical and clinical difference between the included studies, they warn to be more cautious in prescription of PPIs due to the possible result in chronic diseases.

Study lacks important details on study characteristics, including baseline characteristics of study population and duration of follow-up. Authors have excluded low-quality studies for pooled analysis but do not report results of the quality assessment. Many studies have no information on missing data, although this might be due to retrospective design (with exclusion of patients with missing data).

Results for Valuck (2004) are based on only 2 patients with PPI use and 12 patients with H2RA use. Results of study by Lam (2013) are based on H2RA use. Data of both studies will be retrieved from the individual study articles and analysed separately. |

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

Research question: What are the unfavourable effects of long-term use of PPI’s?

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Moayyedi, 2019 |

Type of study: 3x2 partial factorial, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial

Setting and country: 580 centers, 33 contda

Funding and conflicts of interest: Several authors reported COI, two authors are employed at Bayer BV, funding by commercial company. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with stable coronary or peripheral arterial disease, aged ≥65 years. Younger atherosclerotic participants were eligible if they had arterial disease involving 2 cardiovascular beds and/or had 2 additional risk factors.

Exclusion criteria: Patients having a clinical need for long-term PPI Therapy, unwilling to discontinue their H2 receptor antagonist or PPI therapy, a high risk of bleeding from any site, had severe heart failure, significant renal impairment, need for dual antiplatelet therapy, or known hypersensitivity to any of the study drugs.

N total at baseline: Intervention: 8791 Control: 88007

Important prognostic factors2: Age (mean± SD): I: 67.6±8.1 C: 67.7±8.1

Sex (%M): I: 78 C: 79

BMI (mean±SD) I: 28.3±4.7 C: 28.4±4.7

Taking PPI at start of the trial (%) I: 0.6 C: 0.9

Previous peptic ulcer (%) I: 3 C:2.5

Current smoker (%) I: 23,5% C: 23%

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes

|

Pantaprazole 40 mg once daily

|

Placebo

|

Length of follow-up: 3 years( visits at 1 month, 6 months, and then at 6-month intervals)

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: 10/8791 (%) Reasons (NR)

Control: 16/8807 (%) Reasons (NR)

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: 2 (0.02) Reasons (NR))

Control: 1 (0.01%) Reasons (NR)

|

Clostridium difficile infection *(n/N (%)) I: 9/8791 (0.1) C: 24/8807 (<0.1) OR (95%CI): 2.26 (0.70-7.34) P= 0.18

Enteric infection (n/N (%))* I: 119/8791 (1.4) C: 90/8807 (1.0) OR (95%CI): 1.33 (1.01-1.75) P= 0.04

The number needed to harm (95%CI) for enteric infections was 301 (152–9190) after a median of 3 years of PPI use |

Authors conclusion

Remarks Part of the COMPASS-trial, in which patients were randomized to rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily with or without aspirin 100 mg once daily or aspirin 100 mg once daily alone.

Adherence to study medication was assessed by return tablet count at each visit with >80% of medication taken being defined as compliant.

Discontinuation was defined as any patient that permanently discontinued pantoprazole or placebo at any point in the trial and for the remainder of the trial.

Discontinuation of the drug (%): I: 21.4 C: 22.4

Reasons: serious adverse events, patient decision not due to side effect, bleeding, physician decision not due to other event, use of open-label study drug, non-serious adverse event.

|

|

Attwood, 2015 |

Type of study: Open-label randomized controlled trials (SOPRAN-trial and LOTUS-trial)

Setting and country: Multicentre, Europe SOPRAN: 1991 to 2005 LOTUS: 2001 to 2009

Funding and conflicts of interest: Several authors reported COI, two authors are employed at AstraZeneca, funding by commercial company. |

Inclusion criteria: Patients with chronic GERD who were suitable candidates for either treatment. Both studies included only patients who were responsive to initial PPI therapy.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with significant comorbidities and those considered likely to be poorly compliant.

N total at baseline: SOPRAN I: 155 C:155

LOTUS: I: 288 C: 266

Important prognostic factors2: Age (median years): SOPRAN I: 50 C:54

LOTUS: I: 44 C: 46

Sex (% Male) SOPRAN I: 77 C: 75

LOTUS: I: 69 C:75

BMI, previous peptic ulcer, current smoker and PPI at baseline NR

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes |

SOPRAN Omeprazole (20 mg or 40 mg once daily) – 12 years median exposure time

LOTUS Esomeprazole (20 mg once daily, adjusted to 40 mg once daily and then 20 mg twice daily if required)

|

SOPRAN Open ARS – 10 years median exposure time

LOTUS Laparoscopic ARS – 5 years median exposure time

|

Length of follow-up: 5 year (LOTUS-trial) and 12 year (SOPRAN-trial)

Loss-to-follow-up: SOPRAN It is only reported that 7% and 0.6% withdrew before surgery and PPI treatment respectively.

LOTUS** It is only reported that 14% and 0% withdrew before surgery and PPI treatment respectively.

*Details are described in papers on the study design. ** I: 28% was lost to follow-up at 5 year, C: 38% was lost to follow-up at 5 year. *** I: 54% was lost to follow-up after 12 year, C: 63% was lost to follow-up after 12 year

Incomplete outcome data: SOPRAN I: >40/155 C: >50/155 Reasons (NR)

LOTUS I: >1/266 C: >40/288 Reasons (NR)

|

Iron binding capacity (µmol/L) SOPRAN NR

LOTUS - baseline I: 53.9 C:55.0 LOTUS - 1 year I: 54.4 C: 55.7 LOTUS - 3 year I: 53.0 C: 53.5

LOTUS - 5 year I: 55.1 C: 56.7 Effect size: NR P: NR

Ferritin (µ/L) SOPRAN – baseline I: 70 C: 92 SOPRAN – 1 year I: 71 C: 66 Effect size: NR SOPRAN – 3 year I: 67 C: 55 SOPRAN – 5 year I: 79 C: 80

LOTUS - baseline I: 118 C: 111 LOTUS - 1 year I: 131 C: 109 LOTUS - 3 year I: 133 C: 120 LOTUS - 5 year I: 156 C: 122 Effect size: NR P: NR

Gastroenteritis* SOPRAN I: 1 C: 2

LOTUS I: 3 C: 1

*As part of the outcome measure Serious Adverse Events.

|

Authors conclusion No major safety concerns were identified during 5– 12 years of continuous PPI therapy with esomeprazole and omeprazole.

Remarks As a natural consequence of the exceptionally long study periods, many patients discontinued before the end of the SOPRAN (14 years) and LOTUS studies (7 years). To ensure enough data points were available at each time increment for a robust analysis, 12-year and 5-year cut-offs were applied to the SAE analysis sets for the SOPRAN and LOTUS studies respectively. For both laboratory analysis sets, a 5-year cut-off was applied. It should be noted that data patterns beyond these time points are still similar to those reported in this manuscript.

The safety population was defined as all patients who took at least one dose of omeprazole/esomeprazole or received ARS and for whom data were available after treatment initiation.

|

|

Al Ali, 2022 |

Type of study: Cross sectional study

Setting and country: Outpatient clinic, Iraq

Funding and conflicts of interest: Authors declare no COI, no funding reported |

Inclusion criteria: NR

Exclusion criteria: NR

N total at baseline: Intervention: 40 Control: 50

Important prognostic factors2: Age (mean±SD)) I: 42.05±9.57 C: 40.75±8.03

Sex (% M) I: 57.5 C: 56

BMI (mean±SD) I: 31.25±5.91 C: 29.62±6.55

Current smoker and former peptic ulcer NR

Groups comparable at baseline? Patient group had higher weight and BMI. Other relevant characteristics are not reported.

|

Omeprazole (40 mg, long term, at least one year)

|

No medication (healthy patients)

|

Length of follow-up: N.A.

Loss-to-follow-up: N.A.

Incomplete outcome data: N.A.

|

Ferritin (mg/dL) Was estimated by an ELISA I: 18.19±16.19 C: 69.85±53.70 MD (95%CI): NR P=<0.0001 |

Authors conclusion In this study, the objective was to assess the effect of long term omeprazole medication on blood parameters. Omeprazole is very effective in controling gastric acid secretion. Accumulating data suggest that long-term use of omeprazole may lead to a reduction in the numbers of circulating RBCs and their indices, ultimately leading to anemia. We have demonstrated for the first time that long-term use of omeprazole causes vitamin D deficiency. Low level of vitamin D is due to inhibited production of gastric acid which is necessary for calcium mineral absorption, consequently resulting in hypocalcemia. Both hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia may affect the cardiovascular system, therefore, levels of serum magnesium should also be measured to evaluate any abnormality in the serum mineral levels and their relation with cardiovascular health. Omeprazole may be associated with development of kidney functional disorders, therefore, physicians should be cautious when prescribing PPIs because of their adverse effects. A further study with higher number of enrolled patients could assess the various long-term adverse effects of omeprazole medication on the organ systems by performing comprehensive blood and biochemical tests. |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Research question: What are the unfavourable effects of long-term use of PPI’s?

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Islam, 2018 |

Yes, aim, PICO and inclusion criteria of the study are clearly reported. |

Yes, comprehensive search strategy reported. |

Yes, clear description and flowchart of included and excluded studies. |

No, several relevant characteristics are not reported, including age, sex distribution and follow-up period (if applicable). |

No, not reported, although this was taken account in the individual studies. |

Yes, use of Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, although results are not reported in the study article. |

Yes, although, studies do differ with respect to age and sex distribution. |

No, not mentioned |

Yes, no conflicts of interest |

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

Research question: What are the unfavourable effects of long-term use of PPI’s?

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?

Were patients blinded?

Were healthcare providers blinded?

Were data collectors blinded?

Were outcome assessors blinded?

Were data analysts blinded?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Definitely yes Probably yes Probably no Definitely no |

Overall risk of bias If applicable/necessary, per outcome measure

LOW Some concerns HIGH

|

|

Moayyedi, 2019 |

Definitely yes;

Reason: schedules were computer-generated and delivered through an interactive web response system.

|

Definitely yes;

Reason: delivered through an interactive web response system. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Participants, health care staff, and researchers were blinded |

Definitely yes;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no;

Reason: Two authors/researchers are employed at Bayer and were actively involved; Besides, outcomes were assessed during interviews and by checking medical records, which might have led to misclassification/bias towards null.

|

Some concerns (all outcomes)

Reason: two authors/researchers are employed at Bayer (but this seems not to have had an influence on the results) and risk of misclassification.

|

|

Attwood, 2015 LOTUS-trial |

No information |

No information |

Definitely no;

Reason: open-label trial |

Probably no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was different between intervention and control group |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no;

Two authors/ researchers are employed at AstraZeneca and were actively involved |

HIGH

Reason: open-label trial, unclear allocation sequence and concealment, different loss to follow-up, two authors/researchers are employed at AstraZeneca (but this seems not to have had an influence on the results) |

|

Attwood, 2015 SOPRAN-trial |

No information |

No information |

Definitely no;

Reason: open-label trial |

Probably no;

Reason: Loss to follow-up was different between intervention and control group (more in ARS-group) |

Definitely yes;

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported |

Probably no;

Two authors/ researchers are employed at AstraZeneca and were actively involved |

HIGH

Reason: open-label trial, unclear allocation sequence and concealment, two authors/researchers are employed at AstraZeneca (but this seems not to have had an influence on the results) |

Table of excluded studies (voor systematic review search I)

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Aleraij S, Alhowti S, Ferwana M, Abdulmajeed I. Effect of proton pump inhibitors on bone mineral density: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Bone Rep. 2020 Nov 10;13:100732. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2020.100732. PMID: 33299906; PMCID: PMC7701953. |

Wrong outcome measure (focus on bone mineral density) |

|

Briganti SI, Naciu AM, Tabacco G, Cesareo R, Napoli N, Trimboli P, Castellana M, Manfrini S, Palermo A. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Fractures in Adults: A Critical Appraisal and Review of the Literature. Int J Endocrinol. 2021 Jan 15;2021:8902367. doi: 10.1155/2021/8902367. PMID: 33510787; PMCID: PMC7822697. |

No meta-analysis |

|

Chinzon D, Domingues G, Tosetto N, Perrotti M. SAFETY OF LONG-TERM PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS: FACTS AND MYTHS. Arq Gastroenterol. 2022 Apr-Jun;59(2):219-225. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.202202000-40. PMID: 35830032. |

Narrative review |

|

Dahal K, Sharma SP, Kaur J, Anderson BJ, Singh G. Efficacy and Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitors in the Long-Term Aspirin Users: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Ther. 2017 Sep/Oct;24(5):e559-e569. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000637. PMID: 28763306. |

Wrong study population (long-term aspirin users) |

|

Eusebi LH, Rabitti S, Artesiani ML, Gelli D, Montagnani M, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Proton pump inhibitors: Risks of long-term use. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;32(7):1295-1302. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13737. PMID: 28092694. |

Narrative review (methodology unclear) |

|

Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The Risks and Benefits of Long-term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017 Mar;152(4):706-715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031. PMID: 28257716. |

Expert review (AGA) + relevant publications |

|

Hatemi İ, Esatoğlu SN. What is the long term acid inhibitor treatment in gastroesophageal reflux disease? What are the potential problems related to long term acid inhibitor treatment in gastroesophageal reflux disease? How should these cases be followed? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;28(Suppl 1):S57-S60. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.15. PMID: 29199170. |

Short communication, methodology not reported |

|

Hussain MS, Mazumder T. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors adversely affects minerals and vitamin metabolism, bone turnover, bone mass, and bone strength. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2021 Oct 25;33(5):567-579. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2021-0203. PMID: 34687598. |

Narrative review (methodology unclear), focused on several parameters with regards to bone health. |

|

Jaynes M, Kumar AB. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018 Nov 19;10:2042098618809927. doi: 10.1177/2042098618809927. PMID: 31019676; PMCID: PMC6463334. |

Narrative review |

|

Khan MA, Yuan Y, Iqbal U, Kamal S, Khan M, Khan Z, Lee WM, Howden CW. No Association Linking Short-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use to Dementia: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 May;115(5):671-678. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000500. PMID: 31895707. |

Wrong outcome measure (focus on dementia) |

|

Koyyada A. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors as a risk factor for various adverse manifestations. Therapie. 2021 Jan-Feb;76(1):13-21. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2020.06.019. Epub 2020 Jul 9. PMID: 32718584. |

Narrative review, one author |

|

Maes ML, Fixen DR, Linnebur SA. Adverse effects of proton-pump inhibitor use in older adults: a review of the evidence. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2017 Sep;8(9):273-297. doi: 10.1177/2042098617715381. Epub 2017 Jun 29. PMID: 28861211; PMCID: PMC5557164. |

Wrong study population (older adults)?, narrative review |

|

Perry IE, Sonu I, Scarpignato C, Akiyama J, Hongo M, Vega KJ. Potential proton pump inhibitor-related adverse effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020 Dec;1481(1):43-58. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14428. Epub 2020 Aug 6. Erratum in: Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021 Mar;1487(1):74. PMID: 32761834. |

Narrative review (derived from presentations OESO) |

|

Plaut T, Graeme K, Stigleman S, Hulkower S, Woodall T. Clinical Inquiries. How often does long-term PPI therapy cause clinically significant hypomagnesemia? J Fam Pract. 2018 Sep;67(9):576-577. PMID: 30216399. |

Clinical inquiry in journal of family practice |

|

Poly TN, Islam MM, Yang HC, Wu CC, Li YJ. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of hip fracture: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoporos Int. 2019 Jan;30(1):103-114. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4788-y. Epub 2018 Dec 12. PMID: 30539272. |

More extensive review (Islam, 2018) availabe. |

|

Schubert ML. Adverse effects of proton pump inhibitors: fact or fake news? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018 Nov;34(6):451-457. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000471. PMID: 30102612. |

Narrative review (one author) |

|

Sun S, Cui Z, Zhou M, Li R, Li H, Zhang S, Ba Y, Cheng G. Proton pump inhibitor monotherapy and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017 Feb;29(2). doi: 10.1111/nmo.12926. Epub 2016 Aug 30. PMID: 27577963. |

Wrong outcome measure (focus on CV events) |

|

Boghossian TA, Rashid FJ, Thompson W, Welch V, Moayyedi P, Rojas-Fernandez C, Pottie K, Farrell B. Deprescribing versus continuation of chronic proton pump inhibitor use in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Mar 16;3(3):CD011969. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011969.pub2. PMID: 28301676; PMCID: PMC6464703. |

Comparison between deprescribing vs continual use of PPI |

|

Corsonello A, Lattanzio F, Bustacchini S, Garasto S, Cozza A, Schepisi R, Lenci F, Luciani F, Maggio MG, Ticinesi A, Butto V, Tagliaferri S, Corica F. Adverse Events of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Potential Mechanisms. Curr Drug Metab. 2018;19(2):142-154. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666171207125351. PMID: 29219052. |

Focus on potential mechanism of several adverse events of PPI |

|

Dubcenco E, Beers-Block PM, Kim LP, Schotland P, Levine JG, McCloskey CA, Bashaw ED. A Proton Pump Inhibitor in the Reformulation Setting: Bioequivalence and Potential Implications for Long-Term Safety. Clin Transl Sci. 2017 Sep;10(5):387-394. doi: 10.1111/cts.12475. Epub 2017 Jun 15. PMID: 28618191; PMCID: PMC5593167. |

Included wrong study designs (e.g. animal studies), very limited information on results on BMD (outcome was also reported in Aleraij, 2020) |

|

Friedman AJ, Elseth AJ, Brockmeyer JR. Proton Pump Inhibitors, Associated Complications, and Alternative Therapies: A Shifting Risk Benefit Ratio. Am Surg. 2022 Jan;88(1):20-27. doi: 10.1177/0003134821991988. Epub 2021 Feb 9. PMID: 33560890. |

Narrative review |

|

Frieling 2019 Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Long-term Side Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors ? |

Full text not available |

|

Paz MFCJ, de Alencar MVOB, de Lima RMP, Sobral ALP, do Nascimento GTM, Dos Reis CA, Coêlho MDPSS, do Nascimento MLLB, Gomes Júnior AL, Machado KDC, de Menezes APM, de Lima RMT, de Oliveira Filho JWG, Dias ACS, Dos Reis AC, da Mata AMOF, Machado SA, Sousa CDC, da Silva FCC, Islam MT, de Castro E Sousa JM, Melo Cavalcante AAC. Pharmacological Effects and Toxicogenetic Impacts of Omeprazole: Genomic Instability and Cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020 Mar 28;2020:3457890. doi: 10.1155/2020/3457890. PMID: 32308801; PMCID: PMC7146093. |

Focus on mechanism of action of (adverse/protective effects of) omeprazol , included e.g. animal studies |

|

Aghaloo T, Pi-Anfruns J, Moshaverinia A, Sim D, Grogan T, Hadaya D. The Effects of Systemic Diseases and Medications on Implant Osseointegration: A Systematic Review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2019 Suppl;34:s35-s49. doi: 10.11607/jomi.19suppl.g3. PMID: 31116832. |

Wrong study population (implant patients) |

|

Colmenares EW, Pappas AL. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Risk for Myopathy? Ann Pharmacother. 2017 Jan;51(1):66-71. doi: 10.1177/1060028016665641. Epub 2016 Aug 20. PMID: 27539734. |

Narrative review (case reports on myopathy like ADR) |

|

Devitt J, Lyon C, Swanson SB, DeSanto K. What are the risks of long-term PPI use for GERD symptoms in patients > 65 years? J Fam Pract. 2019 Apr;68(3):E18-E19. PMID: 31039222. |

Clinical inquiry in journal of family practice |

|

Rajan P, Iglay K, Rhodes T, Girman CJ, Bennett D, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Risk of bias in non-randomized observational studies assessing the relationship between proton-pump inhibitors and adverse kidney outcomes: a systematic review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022 Feb 10;15:17562848221074183. doi: 10.1177/17562848221074183. PMID: 35173802; PMCID: PMC8841917. |

Wrong outcome (risk of bias in studies)

|

|

Schnoll-Sussman F, Katz PO. Clinical Implications of Emerging Data on the Safety of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2017 Mar;15(1):1-9. doi: 10.1007/s11938-017-0115-5. PMID: 28130652. |

Narrative review (conclusions not clear)

|

|

Schubert ML. Proton pump inhibitors: misconceptions and proper prescribing practice. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2020 Nov;36(6):493-500. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000676. PMID: 32868506. |

Narrative review (one author) |

Table of excluded studies from the meta-analysis of Islam (2018)

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Freedberg DE, Haynes K, Denburg MR, Zemel BS, Leonard MB, Abrams JA, Yang YX. Use of proton pump inhibitors is associated with fractures in young adults: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2015 Oct;26(10):2501-7. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3168-0. Epub 2015 May 19. PMID: 25986385; PMCID: PMC4575851. |

Mostly children and adolescents included. |

|

Luk CP, Parsons R, Lee YP, Hughes JD. Proton pump inhibitor-associated hypomagnesemia: what do FDA data tell us? Ann Pharmacother. 2013 Jun;47(6):773-80. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R556. Epub 2013 Apr 30. PMID: 23632281. |

Number of patients in control group not reported. |

|

Kieboom BC, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Eijgelsheim M, Franco OH, Kuipers EJ, Hofman A, Zietse R, Stricker BH, Hoorn EJ. Proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015 Nov;66(5):775-82. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.05.012. Epub 2015 Jun 26. PMID: 26123862. |

Cross-sectional analysis of data from cohort study. |

|

Lindner G, Funk GC, Leichtle AB, Fiedler GM, Schwarz C, Eleftheriadis T, Pasch A, Mohaupt MG, Exadaktylos AK, Arampatzis S. Impact of proton pump inhibitor use on magnesium homoeostasis: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary emergency department. Int J Clin Pract. 2014 Nov;68(11):1352-7. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12469. Epub 2014 Jun 4. PMID: 24898571. |

Cross-sectional study |

|

Markovits N, Loebstein R, Halkin H, Bialik M, Landes-Westerman J, Lomnicky J, Kurnik D. The association of proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia in the community setting. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014 Aug;54(8):889-95. doi: 10.1002/jcph.316. Epub 2014 May 6. PMID: 24771616. |

Cross-sectional study |

Table of excluded studies Search II

|

Reference |

Reason for exclusion |

|

Abramowitz, J. and Thakkar, P. and Isa, A. and Truong, A. and Park, C. and Rosenfeld, R. M. Adverse Event Reporting for Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery (United States). 2016; 155 (4) :547-554 |

SR of SRs |

|

Al Ali, H. S. and Jabbar, A. S. and Neamah, N. F. and Ibrahim, N. K. Long-Term Use of Omeprazole: Effect on Haematological and Biochemical Parameters. Acta medica Indonesiana. 2022; 54 (4) :585-594 |

Cross-sectional study |

|

Caos, A. and Breiter, J. and Perdomo, C. and Barth, J. Long-term prevention of erosive or ulcerative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease relapse with rabeprazole 10 or 20 mg vs. placebo: Results of a 5-year study in the United States. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005; 22 (3) :193-202 |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Freston, J. W. and Hisada, M. and Peura, D. A. and Haber, M. M. and Kovacs, T. O. and Atkinson, S. and Hunt, B. The clinical safety of long-term lansoprazole for the maintenance of healed erosive oesophagitis. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2009; 29 (12) :1249-1260 |

Wrong outcomes |

|

Roncarati G, Dallolio L, Leoni E, Panico M, Zanni A, Farruggia P. Surveillance of Clostridium difficile Infections: Results from a Six-Year Retrospective Study in Nine Hospitals of a North Italian Local Health Authority. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jan 10;14(1):61. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010061. PMID: 28075419; PMCID: PMC5295312. |

Wrong definition of PPI use (within 30 days before CDI) |

|

Seo, S. I. and You, S. C. and Park, C. H. and Kim, T. J. and Ko, Y. S. and Kim, Y. and Yoo, J. J. and Kim, J. and Shin, W. G. Comparative risk of Clostridium difficile infection between proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonists: A 15-year hospital cohort study using a common data model. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Australia). 2020; 35 (8) :1325-1330 |

Wrong definition of PPI use (≥7 days) |

|

Thurber, K. M. and Otto, A. O. and Stricker, S. L. Proton pump inhibitors: Understanding the associated risks and benefits of long-term use. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2023; 80 (8) :487-494 |

Narrative review |

|

Caos, A. and Breiter, J. and Perdomo, C. and Barth, J. Long-term prevention of erosive or ulcerative gastro-oesophageal reflux disease relapse with rabeprazole 10 or 20 mg vs. placebo: Results of a 5-year study in the United States. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005; 22 (3) :193-202 |

Double result |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 14-10-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 14-10-2024

Geplande herbeoordeling : 14-10-2026

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). Patiëntenparticipatie bij deze richtlijn werd medegefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Patiënten Consumenten (SKPC) binnen het programma KIDZ.

De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2021 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van de werkgroep) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met GORZ.

Werkgroep

- Prof. dr. A.J. Bredenoord, MDL-arts, Amsterdam UMC, NVMDL (voorzitter)

- Dr. J.M. Conchillo, MDL-arts, Maastricht UMC+, NVMDL

- Dr. R.C.H. Scheffer, MDL-arts, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, NVMDL