Profylactische behandeling bij epilepsie

Uitgangsvraag

Welk type, dosis en vorm van primaire profylactische anti-epileptische behandeling moet worden toegediend aan patiënten met hersentumoren om epileptische aanvallen te voorkomen?

Aanbeveling

Schrijf geen geen anti-aanvalsmedicatie als primaire profylaxe bij patiënten met een hersentumor voor, vanwege onvoldoende bewijs voor effectiviteit.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Gekeken naar de conclusies over de cruciale uitkomstmaat ‘effectiviteit’ is er met zeer weinig zekerheid te zeggen of er sprake is van een klinisch relevant effect van profylactische anti-epileptische medicatie bij patiënten met een hersentumor in vergelijking met een placebo of geen behandeling. Alleen wanneer fenytoïne (of fenobarbital) werd vergeleken met een controlegroep, werd er een klinisch relevant effect gevonden in het voordeel van de profylactische anti-epileptische medicatie. Wanneer valproaat werd vergeleken met placebo was juist de controlegroep in het voordeel. De bewijskracht voor deze gevonden effecten was echter zeer laag vanwege de brede betrouwbaarheidsintervallen (imprecisie) en het risico op bias. Gekeken naar de conclusies met betrekking tot de belangrijke uitkomstmaat ‘tolerantie’ kan er ook geen eenduidig besluit worden genomen over welke interventie de voorkeur heeft. Er lijkt een klinisch relevant nadeel te zijn van fenytoïne/fenobarbital of valproaat behandeling in vergelijking met geen behandeling/placebo. Hierbij betreft het bijwerkingen van de gebruikte medicatie, zoals vermoeidheid en cognitieve klachten. Deze gevonden effecten hadden een lage bewijskracht vanwege het risico op bias. Dit betekent dat nieuwe studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Het belangrijkste doel van de interventie is het voorkómen van epileptische aanvallen bij patiëntengroep die at risk is. Het meest belangrijke voordeel van een interventie zou het uitblijven van aanvallen zijn. Het relevantste nadeel van een behandeling is dat er bijwerkingen zouden kunnen optreden. Hierbij dient in acht genomen te worden dat het ernstige zieke patiëntgroep is (met name de patiënten met een hooggradig glioom of IDH-wild type glioom, en de patiënten met hersenmetastasen) die vaak al verschillende behandelingen krijgen, waarbij zowel interacties tussen medicijnen als versterking van bijwerkingen op de loer liggen. Aan de andere kant zijn, zeker bilateraal tonisch-clonische, aanvallen een zware belasting voor deze patiënten. Er is daarbij een verschil aan te geven tussen enerzijds patiënten met een laaggradig glioom of IDH-gemuteerd glioom en anderzijds patiënten met een IDH-wild type glioom of hersenmetastasen. De eerste groep patiënten (laaggradig glioom of IDH-gemuteerd glioom) leidt vaak lange tijd een onveranderd sociaal en maatschappelijk leven, met daarbij een andere balans tussen de dreiging van een aanval en de bijwerkingen van profylactische anti-aanvalsmedicatie dan bij de tweede groep, die ernstiger ziek is.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er dient een afweging gemaakt te worden tussen de kosten van het gebruik van anti-aanvalsmedicatie enerzijds en de kosten van co-morbiditeit en extra ziekenhuisopnamen in verband met epileptische aanvallen anderzijds. De clustergroep is niet bekend met economische evaluaties. De anti-aanvalsmedicatie (bijvoorbeeld fenobarbital, fenytoïne, valproaat) die in de literatuur worden onderzocht zijn relatief goedkoop (Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas, 2022).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Er is geen kwantitatief of kwalitatief onderzoek gedaan naar de aanvaardbaarheid en haalbaarheid van profylactische behandeling bij patiënten met primaire hersentumoren of metastasen. Ongeacht de werking van de middelen, zijn de bijwerkingen van de middelen een groot bezwaar voor zowel de behandelend zorgverlener als voor de patiënt. Er zijn meer kwalitatief hoogwaardige studies nodig om te beoordelen of de bijwerkingen van profylactische behandeling opwegen tegen de eventuele voordelen met betrekking tot het voorkomen van epileptische aanvallen. De aanbeveling zal geen invloed hebben op gezondheidsgelijkheid, omdat de huidige aanbeveling de huidige manier van werken niet zal beïnvloeden. Mocht in de toekomst blijken dat profylactische behandeling wel zinvol is, dan zal dit waarschijnlijk ook geen invloed hebben op gezondheidsgelijkheid. Iedereen in Nederland heeft toegang tot de interventie. Wanneer profylactische behandeling toegepast zou worden zijn er geen andere belemmerende factoren die een rol spelen bij op het gebied van implementatie (zoals kosten). Ook zijn er geen bevorderende maatregelen of randvoorwaarden nodig. De subgroepen waar rekening mee moet worden gehouden zijnde groep patiënten met een minder (laaggradig of Isocytraat Dehydrogenase (IDH)-gemuteerd glioom) en meer (hooggradig of (IDH)-wild type glioom en hersenmetastasen) agressieve tumor. Bij beide groepen zal de afweging tussen de dreiging van een epileptische aanval en de impact van bijwerkingen op het dagelijks functioneren anders zijn, en hiermee ook de noodzaak voor de profylactische behandeling in samenspraak met de patiënt en naasten, anders worden ingeschat. De clustergroep is niet bekend met studies waarin het profylactisch gebruik van anti-aanvalsmedicatie bij kinderen wordt onderzocht.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

De beschikbare studies geven geen ondersteuning voor het primair profylactisch gebruik van anti-aanvalsmedicatie bij patiënten met hersentumoren.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In de ideale situatie kunnen patiënten met een hoog a priori risico op het ontwikkelen van epilepsie, bijvoorbeeld patiënten met hersentumoren, profylactisch behandeld worden met anti-aanvalsmedicatie zodat zij geen epileptische aanvallen krijgen. Het is onduidelijk of anti-aanvalsmedicatie het ontwikkelen van epilepsie bij deze patiëntengroep tegen kunnen gaan. Daarnaast heerst het de vraag of mogelijke nadelen van profylactische behandeling (bijvoorbeeld bijwerkingen van anti-aanvalsmedicatie, interacties met comedicatie) opwegen tegen de eventuele profylactische werking.

Deze module evalueert de rol van profylactische behandeling bij patiënten met hersentumoren of hersenmetastasen. Deze module bevat een update van de module ‘Oncologie: profylactische behandeling’ (juni 2020).

Conclusies

1. Phenytoin versus no treatment / placebo

1.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

| Low GRADE | Phenytoin may reduce early seizures when compared with no treatment or placebo in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery. However, phenytoin may result in a slight increase in late seizures when compared with no treatment or placebo in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery.

Sources: Forsyth, 2003; Lee, 1989; North, 1983; Wu, 2013 |

1.2 Adverse events (important)

| Low GRADE | Phenytoin may increase adverse events when compared with no treatment or placebo in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery.

Sources: Forsyth, 2003 |

2. Phenytoin or phenobarbital versus no treatment

2.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

| Very low GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of phenytoin or phenobarbital on seizure incidence when compared with no treatment in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery.

Sources: Franceschetti, 1990 |

2.2 Adverse events (important)

| Very low GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of phenytoin or phenobarbital on adverse events when compared with no treatment in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery.

Sources: Franceschetti, 1990 |

3. Valproic acid versus placebo

3.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

| Very low GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of valproic acid on seizure incidence when compared with placebo in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery.

Sources: Gliantz, 1996 |

3.2 Adverse events (important)

| Very low GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of valproic acid on adverse events when compared with placebo in patients with brain tumours or metastases undergoing brain surgery.

Sources: Gliantz, 1996 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Tremont-Lukats (2008) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis, and evaluated the effect of prophylactic antiepileptic drugs on seizures and adverse events in people with brain tumours. A systematic literature search was performed from 1966 to 2007. Studies were included if they 1) were controlled clinical trials with random allocation; 2) included patients with glioma, meningiomas, skull base tumours and brain metastases from any primary tumour; 3) compared prophylactic antiepileptics with no prophylaxis or prophylaxis with a placebo; 4) described the proportion of individuals free from seizures and/or adverse event rate as outcome measures. Studies were excluded if two anticonvulsants were compared. In total, five studies comprising 468 patients were included in our analysis of the literature (Forsyth, 2003; Franceschetti, 1990; Glantz, 1996; Lee, 1989; North, 1983) and also met our inclusion criteria. Characteristics of the individual studies are summarized in the evidence tables. Outcome measures included effectiveness (by seizure occurrence) and tolerance (by the adverse event rate). Risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Wu (2013) performed a randomized controlled trial, including 123 patients with intraparenchymal, supratentorial brain tumours (proven by biopsy or compelling CT/MRI). This study examined the use of phenytoin for post-operative seizure prophylaxis in patients with supratentorial brain metastases or gliomas undergoing surgical resection. Patients were randomly assigned in two groups. The intervention group (n=62, median age 56y; 60% men) received 15mg/kg of phenytoin intravenously in the operating room prior to commencing the craniotomy, followed by 100 mg every eight hours for seven days after surgery. Thereafter, the dose was tampered down with a 100 mg decrease every two days. The control group (n=61, median age 61y, 49% male) did not receive any phenytoin before or after surgery. The follow-up was 12 months. Outcome measures included effectiveness (by seizure incidence and tolerance (by minor and major adverse events).

Table 1. Summary of study characteristics

| Study | Population | Intervention | Control | Outcomes | Risk of bias |

| Tremont-Lukats, 2008 | |||||

| Forsyth, 2003 | N=100

| Phenytoin (15mg/kg) in 3 divided doses, followed by 5 mg/kg po qd.(n=46) | No treatment (n=54) | Seizure incidence Adverse events

Follow-up: >12 months | Lack of blinding of subjects and investigators. Heterogenous study population (brain metastases and low-grade gliomas) Selection bias (seizure could have been occurred between the diagnosis and randomization) |

| Franceschetti, 1990 | N=63 who never seized (27 meningioma, 23 malignant glioma, 13 metastases) | Group A; n=25: Phenobarbital (4mg/kg/day for 5 days, then 2mg/kg/day) Group B; n=16: Phenytoin (10 mg/kg/day for 5 days, then 5 mg/kg/day) | No treatment (n=22) | Seizure incidence (early postoperative and late)

Averse events (total)

| Absence of allocation concealment. Unclear sequence generation. |

| Glantz, 1996 | N=74 (51 lung cancer, 2 non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 4 glioblastoma, 2 melanoma, 4 breast cancer, 5 GBM, 6 other) | Valproic acid (50-100 ug/mL) (n=37) | Placebo (n=37) | Seizure incidence

Adverse events

Median follow-up: 7 months. | Lack of blinding of the study staff to the drug dose. |

| Lee, 1989 | N=85 (50 meningioma, 30 glioma, 5 metastases) | Phenytoin (15 mg/kg intravenously before wound closure, then 5-6 mg/kg/day intravenously) (n=44) | Placebo (n=42) | Seizure incidence (immediate and early postoperative) | No description of allocation concealment. |

| North, 1983 | N=81 (19 meningioma, 13 metastasis, 17 sellar tumour, 32 glioma) | Phenytoin (250 mg twice daily intravenously, then 100 mg orally three times daily for 12 months) (n=42) | Placebo (n=39) | Seizure incidence

Follow-up: 1 month after surgery. | Unclear sequence generation. Unclear allocation concealment. |

| Wu, 2013 | N= 123 (77 metastases and 46 gliomas) | Phenytoin (loading dose of 15 mg/kg intravenously in the operating room prior to craniotomy, followed by 100 mg every 8 hours for 7 days post-operatively, then tapered starting at post-operative day 8 with 100 mg dosage decrease every 2 days) (n=62) | No treatment (n=61) | Seizure incidence (within 30 days of surgery or more than 30 days after surgery) | Selective outcome reporting (therapeutic blood levels during the first critical days after surgery in the intervention group is a confounding factor for seizures). |

Results

1. Phenytoin versus no treatment / placebo

1.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

Effectiveness was assessed by the incidence of seizures in the early phase after surgery (within one month after surgery) and in the late phase after surgery (up to more than 12 months after surgery).

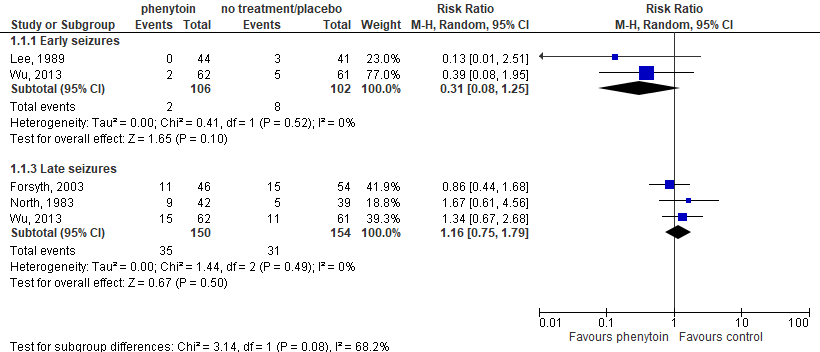

Early seizures

Two studies (Lee, 1989; Wu, 2013) assessed the number of seizures within the first month after surgery after administration of phenytoin (n=106) versus no treatment/placebo (n=102). Early seizure incidence was 1.9% in patients receiving phenytoin compared to 7.8% in patients receiving no treatment or placebo. This corresponds to a risk ratio of 0.31 (95%CI 0.08 to 1.25), thus patients receiving phenytoin had a 69% lower risk of early seizures compared to patients receiving no treatment or placebo. This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the phenytoin group. Results are shown in a forest plot, see Figure 1.

Late seizures

Three studies (Forsyth, 2003; North, 1983; Wu, 2013) assessed the number of seizures up to more than 12 months after surgery after administration of phenytoin (n=150) versus no treatment/placebo (n=154). Late seizure incidence was 23.3% in patients receiving phenytoin compared to 20.1% in patients receiving no treatment or placebo. This corresponds to a risk ratio of 1.16 (95%CI 0.75 to 1.79), thus patients receiving phenytoin had a 16% higher risk of seizures compared to patients receiving no treatment or placebo. This difference was not clinically relevant. Results are shown in a forest plot, see Figure 1.

Figure 1. Forest plot of seizure incidence

1.2 Adverse events (important)

Tolerance was assessed by the incidence of total adverse events up to more than 12 months after surgery in one study that compared phenytoin treatment (n=46) versus no treatment (n=54) (Forsyth, 2003). Adverse event incidence was 13% in patients receiving phenytoin compared to 0% in patients receiving no treatment. This corresponds to a risk difference of 0.28 (95%CI 0.15 to 0.41), thus 28 extra adverse events occurred per 100 patients in the group receiving phenytoin compared to the group receiving no treatment. This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the no treatment group.

2. Phenytoin or phenobarbital versus no treatment

2.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

Effectiveness was assessed by the incidence of seizures in the early phase after surgery and in the late phase after surgery after administering phenytoin/phenobarbital (n=41) or no treatment (n=22) by Franceschetti (1990).

Early seizures

Franceschetti (1990) reported an early seizure incidence of 7.3% in patients receiving phenytoin or phenobarbital compared to 18.2% in patients receiving no treatment. This corresponds to a risk ratio of 0.40 (95%CI 0.10 to 1.64), so patients receiving phenytoin or phenobarbital had a 60% lower risk of early seizures compared to patients receiving no treatment. This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the phenytoin/phenobarbital group.

Late seizures

Franceschetti (1990) reported on incidence of late seizure in the remaining patients after follow-up (n=39). In patients receiving phenytoin or phenobarbital (n=25), seizure incidence was 12% compared to 21.4% in patients receiving no treatment (n=14). This corresponds to a risk ratio of 0.56 (95%CI 0.13 to 2.41), so patients receiving phenytoin or phenobarbital had a 44% lower risk of total seizures compared to patients receiving no treatment. This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the phenytoin/phenobarbital group.

2.2 Adverse events (important)

Tolerance was assessed by the incidence of total adverse events after administering phenytoin/phenobarbital (n=41) or no treatment (n=22) by Franceschetti (1990). Adverse event incidence was 9.8% in patients receiving phenytoin or phenobarbital compared to 0% in patients receiving no treatment. This corresponds to a risk ratio of 0.10 (95%CI -0.01 to 0.21), so 10 extra adverse events occurred per 100 patients in the group receiving phenytoin or phenobarbital compared to the group receiving no treatment. This difference was clinically relevant in favour of the no treatment group.

3. Valproic acid versus placebo

3.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

Effectiveness was assessed by the incidence of seizures up to seven months follow-up after surgery after administering valproic acid (n=37) or placebo (n=37) by Glantz (1996). Seizure incidence was 35.1% in patients receiving valproic acid compared to 24.3% in patients receiving placebo. This corresponds to a risk ratio of 1.44 (95%CI 0.70 to 2.96), so patients receiving valproic acid had a 44% higher risk of seizures compared to patients receiving placebo. This difference was clinically relevant in favour of placebo.

3.2 Adverse events (important)

Tolerance was assessed by the incidence of adverse events up to seven months follow-up after surgery after administering valproic acid (n=37) or placebo (n=37) by Glantz (1996). Adverse event incidence was 5.4% in patients receiving valproic acid compared to 2.7% in patients receiving placebo. This corresponds to a risk difference of 0.03 (95%CI -0.06 to 0.12), so three extra adverse events occurred per 100 patients in the group receiving valproic acid compared to the group receiving placebo. This difference was not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

RCTs start at a high level of evidence.

1. Phenytoin versus no treatment / placebo

1.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome effectiveness was downgraded by two levels due to study limitations (-1, risk of bias) and crossing the border of clinical relevance (-1, imprecision). The final level is low.

1.2 Adverse events (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome adverse events was downgraded by two levels due to the heterogenous study population and selection bias (-2, risk of bias). The final level is low.

2. Phenytoin or phenobarbital versus no treatment

2.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome effectiveness was downgraded by three levels due to absence of allocation concealment (-1, risk of bias) and limited number of included patients (-2, imprecision). The final level is very low.

2.2 Adverse events (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome adverse events was downgraded by three levels due to absence of allocation concealment (-1, risk of bias) and limited number of included patients (-2, imprecision). The final level is very low.

3. Valproic acid versus placebo

3.1 Effectiveness (crucial)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome effectiveness was downgraded by three levels due to lack of blinding (-1, risk of bias) and crossing the borders of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision). The final level is very low.

3.2 Adverse events (important)

The level of evidence regarding the outcome adverse events was downgraded by three levels due to lack of blinding (-1, risk of bias) and crossing the borders of clinical relevance (-2, imprecision). The final level is very low.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

What is the effectiveness of primary seizure prophylaxis compared to no treatment or placebo in patients with brain tumors or brain metastases?

P: Patients with brain tumors or brain metastases without seizures so far

I: Prophylactic anti-seizure treatment

C: No treatment, placebo

O: Effectiveness, tolerance

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered effectiveness as a critical outcome measure for decision making, and tolerance as an important outcome measure for decision making.

The working group defined the following outcome measures:

- Effectiveness: seizure incidence, seizure freedom (Engel/ILAE classification), seizure response, or seizure recurrence.

- Tolerance: any adverse effects/events of tolerability reported.

Per outcome, the working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences.

- Seizure (incidence): RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous); 0.5 SD (continuous)

- Adverse events: RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous); 0.5 SD (continuous)

Search and select (Methods)

The search strategy dated from 01-01-2019 was updated. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 01-01-2019 (last search) until 21-06-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The search was limited to systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials. The systematic literature search resulted in 35 hits. Studies for this module were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) or randomized controlled trial;

- full-text English language publication; and

- studies according to the PICO.

Seventeen studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 14 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and two studies were included in the literature summary of this module.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature, of which one systematic review and one randomized controlled trial (thus no additional studies were found compared to the previous module dated from 2020). Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables and Table 1. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Farmacotherapeutisch Kompas, 2022. Geneesmiddelen. Geraadpleegd op 25 januari 2022: https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/preparaatteksten/f/fenobarbital; https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/preparaatteksten/f/fenytoine; https://www.farmacotherapeutischkompas.nl/bladeren/preparaatteksten/v/valproinezuur

- Tremont-Lukats IW, Ratilal BO, Armstrong T, Gilbert MR. Antiepileptic drugs for preventing seizures in people with brain tumours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Apr 16;(2):CD004424. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004424.pub2. PMID: 18425902.

- Walbert T, Harrison RA, Schiff D, Avila EK, Chen M, Kandula P, Lee JW, Le Rhun E, Stevens GHJ, Vogelbaum MA, Wick W, Weller M, Wen PY, Gerstner ER. SNO and EANO practice guideline update: Anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2021 Nov 2;23(11):1835-1844. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab152. PMID: 34174071; PMCID: PMC8563323.

- Wu AS, Trinh VT, Suki D, Graham S, Forman A, Weinberg JS, McCutcheon IE, Prabhu SS, Heimberger AB, Sawaya R, Wang X, Qiao W, Hess K, Lang FF. A prospective randomized trial of perioperative seizure prophylaxis in patients with intraparenchymal brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 2013 Apr;118(4):873-883. doi: 10.3171/2012.12.JNS111970. Epub 2013 Feb 8. PMID: 23394340; PMCID: PMC4083773.

Evidence tabellen

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Intervention (I) | Comparison / control (C)

| Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments |

| Tremont-Lukats, 2008 | SR and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials.

Literature search up to 2007

A: Forsyth, 2003 B: Frranceschetti, 1990 C: Glantz, 1996 D: Lee, 1989 E: North, 1983

Study design: A: RCT B: RCT C: RCT D: RCT E: RCT

Setting and Country: A: Multicenter, Canada, US. B: 1 tertiary car neurological institute, Italy. C: 4 hospitals, US. D: 1 tertiary care hospital, Taiwan. E: 1 tertiary care hospital, Italy.

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: A: Supported by the Alberta Cancer Board and the Foothills Hospital Foundation. We thank our patients and their families for participating in this study and Ms. Eve Lee for her expert editorial assistance. B: n.r. C: Supported in part by a National Institute of Health Cancer Center CORE grant (CA-13943). Divalproex Sodium (Depakote") and identical-appearing placebo tablets were provided by Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL. D: n.r. E: n.r.

| Inclusion criteria SR: Controlled clinical trials with random allocation, blinded or unblinded. Participants with diagnosis of glioma, using theWorldHealthOrganization (WHO) classification of brain tumors (astrocytomas grades II, III, and IV; oligodendrogliomas grades II and III; ependymomas grades II and III);meningiomas; skull base tumors, and brain metastases from any primary tumor. Prophylactic antiepileptics (treatment intervention) compared with no prophylaxis or prophylaxis with a placebo (control intervention). Participants may have had surgery for the diagnosis or treatment of the underlying tumour.

Exclusion criteria SR: We excluded studies comparing two anticonvulsants.

5 studies included

Important patient characteristics at baseline: N, mean age A: 100 patients, 56 yrs. B: 63 patients, 55 yrs. C: 74 patients, 63 yrs. D: 85 patients, E: 81 patients,

Sex: A: 61% Male B: 54% Male C: 55% Male D: E:

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes | Describe intervention:

A: Phenytoin (15mg/kg) in 3 divided doses, followed by 5 mg/kg po qd.(n=46) B: Group A; n=25: Phenobarbital (4mg/kg/day for 5 days, then 2mg/kg/day); Group B; n=16: Phenytoin (10 mg/kg/day for 5 days, then 5 mg/kg/day) E: Phenytoin (250 mg twice daily intravenously, then 100 mg orally three times daily for 12 months) (n=42

| Describe control:

A: No treatment (n=54) B: No treatment (n=22) C: Placebo (n=37) D: Placebo (n=42) E: Placebo (n=39)

| End-point of follow-up:

A: > 12 months B: > 6 months C: 7 months D: Immediate and early postoperative. E: 1 month

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N (%) A: 8 (8%) B: 22 (26%) shorter than 6 months. C: 13 (14%) D: E:

| Effectiveness Defined as seizure incidence Effect measure: RR [95% CI]: Early:

Late: A: 0.86 [0.44 to 1.68] in faovur of phenytoin.

Tolerance Defined as total adverse event incidence Effect measure: RD [95% CI]: A: 0.28 [0.15 to 0.41] in favour of no treatment.

| Author’s conclusion: The evidence for seizure prophylaxis with phenobarbital, phenytoin, and divalproex sodium in people with brain tumours is inconclusive, at best. The clinical heterogeneity between and within trials limits any claim of effectiveness or ineffectiveness. Therefore, there are no data supporting the use of prophylactic antiepileptics and the risk of adverse events lessens their overall potential benefit. Use of these antiepileptic drugs is associated with a higher risk of adverse events than in a control group, which is a major factor to consider when deciding to start seizure prophylaxis.

Risk of bias:

|

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics 2 | Intervention (I) | Comparison / control (C) 3

| Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size 4 | Comments |

| Wu, 2013 | Type of study: A Prospective Randomized Trial

Setting and country: Department of neurosurgery, USA.

Funding and conflicts of interest: This work was supported by grants from the Elias Family Fund for Brain Tumor Research, Brian McCulloch Research Fund, Gene Pennebaker Brain Cancer Fund, and the Sorenson Fund. We wish to thank them for their generosity. | Inclusion criteria: Patients with intraparenchymal, supratentorial brain tumours either proven by biopsy to be a brain metastasis or a glioma, or with compelling CT or MRI evidence of metastasis or glioma were selected for this study. All patients had to be previously untreated, with the exception of whole brain radiation therapy greater than four weeks prior to enrolment, and all patients had to undergo craniotomy for resection of their brain tumour, with the goal of maximal safe resection of the targeted lesion. All eligible patients also had to have had no seizure on presentation prior to entering the study, and not have received any prophylactic AED therapy prior to enrolment. Other inclusion criteria were: age 8 years or older, Karnofsky Performance Scale (KPS) score ≥ 70, and normal electrolytes (Na, K, Mg, PO4, and Ca within 10% of institutional normal) prior to surgery.

Exclusion criteria: Patients a history of epilepsy or seizures, solely posterior fossa tumours, the existence of any other past or concomitant intracranial pathology, prior toxicity to phenytoin, whole brain radiation therapy within 4 weeks of enrolment, any previous surgical resection other than stereotactic biopsy, leptomeningeal disease, elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT and bilirubin ≥ 3 times institutional normal), lactation and pregnancy (diagnosed by β-HCG ≥ 5 mIU/mL).

N total at baseline: Intervention: 62 Control: 61

Important prognostic factors2: Age (IQR): I: 56 (16-80) C: 61 (35-84)

Sex: I: 60% M C: 49% M

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes | Describe intervention:

Patients randomized to the prophylaxis group received a loading dose of Phenytoin (15mg/kg IV) in the operating room prior to commencing the craniotomy, followed by 100 mg every 8 hr (orally or intravenously) for 7 days post-operatively, and then tapered starting at post-operative day 8 with a 100 mg dosage decrease every two days until discontinuation. Phenytoin levels were drawn immediately after surgery and then daily in the morning while patients were in hospital. Additional boluses and/or changes in daily dosing were made as needed per the primary physician's judgment, with a therapeutic goal of maintaining phenytoin levels between 10 and 20 mg/L. Serum phenytoin levels were also measured at the day 8 follow-up.

| Describe control:

Patients randomized to the observation group did not receive any phenytoin before or after surgery until the end of their participation in the study, defined by death, definite seizure, or at the 12-month follow-up evaluation, or if informed consent was withdrawn. | Length of follow-up: 30 days after surgery and >30 days.

Loss-to-follow-up: n.r.

Incomplete outcome data: n.r.

| Effectiveness Defined as seizure incidence. Effect measure: RR [95% CI] Early 0.39 [0.08 to 1.95] in favour of phenytoin.

Late 1.34 [0.67 to 2.68] in favour of no treatment.

Tolerance n.r.

| Author’s conclusion There is no consensus among neurosurgeons treating patients with brain tumours regarding the use of peri-operative prophylactic AEDs. The low rates of seizures seen in the control arm of this prospective trial raise serious concerns about the routine use of peri-operative prophylactic phenytoin in patients with brain tumours may not be warranted. |

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors [(potential) confounders]

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Study

| Appropriate and clearly focused question?1 | Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

| Description of included and excluded studies?3 | Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4 | Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

| Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6 | Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7 | Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

| Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

|

| Tremont-Lukats, 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials; based on Cochrane risk of bias tool and suggestions by the CLARITY Group at McMaster University)

| Study reference | Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? a

| Was the allocation adequately concealed?b

| Blinding: Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented?c | Was loss to follow-up (missing outcome data) infrequent?d

| Are reports of the study free of selective outcome reporting?e

| Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?f

| Overall risk of bias If applicable/ necessary, per outcome measureg

|

| Wu, 2013 | No information;

Reason: No information was provided. | No information;

Reason: No information was provided. | Definitely yes;

Reason: Outcomes were assessed by a blinded neurologist. | Probably yes

Reason: Loss to follow-up was infrequent in intervention and control group. | Definitely yes

Reason: All relevant outcomes were reported; | Definitely no;

Reason: The trial was closed before reaching its planned accrual of 142 patients. | Some concerns (violation of intention-to-treat analysis). |

- Randomization: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomization process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomization (performed at a site remote from trial location). Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomization procedures or open allocation schedules..

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments, but this should not affect the risk of bias judgement. Blinding of those assessing and collecting outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignment influences the process of outcome assessment or data collection (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is usually not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary. Finally, data analysts should be blinded to patient assignment to prevents that knowledge of patient assignment influences data analysis.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up or the percentage of missing outcome data is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up or missing outcome data differ between treatment groups, bias is likely unless the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is not enough to have an important impact on the intervention effect estimate or appropriate imputation methods have been used.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available (in publication or trial registry), then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- Problems may include: a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used (e.g. lead-time bias or survivor bias); trial stopped early due to some data-dependent process (including formal stopping rules); relevant baseline imbalance between intervention groups; claims of fraudulent behavior; deviations from intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; (the role of the) funding body. Note: The principles of an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

- Overall judgement of risk of bias per study and per outcome measure, including predicted direction of bias (e.g. favors experimental, or favors comparator). Note: the decision to downgrade the certainty of the evidence for a particular outcome measure is taken based on the body of evidence, i.e. considering potential bias and its impact on the certainty of the evidence in all included studies reporting on the outcome.

Table of excluded studies

| Author and year | Reason for exclusion |

| Moon, 2021 | Guideline |

| Delgado, 2020 | Article in Spanish |

| Rudã, 2020 | Narrative review |

| Roth, 2021 | Guideline |

| Pan, 2021 | Does not fulfil PICO (prediction study) |

| Mathew, 2020 | Did not describe outcome measures as defined in our PICO |

| Yang, 2020 | Observational study |

| Wolpert, 2020 | Does not fulfil PICO (prediction study) |

| Harward, 2020 | Book chapter, not accessible and does not contain original data. |

| Zoccarato, 2021 | Narrative review |

| Kutteruf, 2018 | Describes the wrong patient group |

| Kamenova, 2020 | Observational study |

| Youngerman, 2020 | Based on pharmacy claims data. |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 30-05-2023

Laatst geautoriseerd : 21-11-2022

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-01-2024

In onderstaande tabel is de geldigheid te zien per richtlijnmodule. Tevens zijn de aandachtspunten vermeld die van belang zijn voor een herziening. Het cluster Epilepsie is als houder van deze richtlijn de eerstverantwoordelijke voor de actualiteit van deze richtlijn.

|

Module |

Geautoriseerd in |

Laatst beoordeeld in |

Geplande herbeoordeling |

Wijzigingen meest recente versie |

|

|

1. Startpagina - Epilepsie |

2022 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

2. Informatie voor patiënten |

2022 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

3. Definities en epidemiologie |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

4. Classificatie |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

5. Elektrofysiologisch onderzoek |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

6. Neuropsychologisch onderzoek |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

7. Immunologie |

|||||

|

7.1. Diagnostiek |

2019 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

7.2. Therapie |

7.2.1. Immunotherapie |

2019 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

7.2.2. Anti-epileptica |

2019 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

8. Beeldvormend onderzoek |

2016 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

9. Cardiologisch onderzoek |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

10. Genetisch onderzoek |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

11. Anti-epileptica |

|||||

|

11.1. Wanneer starten |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

11.2. Mono- of combinatie therapie |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

11.3. Welk anti-epilepticum |

11.3.1. Aanvallen met een focaal begin |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

2022: Module compleet herzien |

|

11.3.2. Aanvallen met een gegeneraliseerd begin |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

11.3.3. Aanvallen met een onbekend begin |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

11.4. Algemene anti-epileptica |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

11.5. Wanneer staken |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

11.6. Generiek of specialité |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 1 jaar |

|

|

|

11.7. Cannabidiol |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

12. Status epilepticus |

|||||

|

12.1. |

12.1.1. Couperen buiten het ziekenhuis en op de spoedeisende hulp |

2022 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

2022: Module compleet herzien |

|

12.1.2. Refractaire status |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

12.2. |

12.2.1. Initiële behandeling |

2022 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

2022: Module compleet herzien |

|

12.2.2. Refractaire status |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

12.2.3. Focale status |

2022 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

12.2.4. Non-convulsieve status |

2017 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

13. Bewaking bij anti-epilepticagebruik |

|||||

|

13.1. Monitoren serumspiegels anti-epileptica |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

13.2. Monitoren klinisch-chemische en hematologische parameters |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

13.3. Screening op osteoporose |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

14. Epilepsiechirurgie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

2022: tekstuele optimalisatie (n.a.v. herziening vijf modules) |

|

|

15. Neurostimulatie |

|||||

|

15.1. Nervus vagus stimulatie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

15.2. Diepe hersen stimulatie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar

|

|

|

|

16. Ketogeen dieet |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

17. Epilepsiesyndromen (bij kinderen) & anti-epileptica |

|||||

|

17.1. Absence epilepsie

|

17.1.1. Eerste keus medicatie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

17.1.2. Tweede keus medicatie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.1.3. EEG en medicatie |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.2. Juveniele myoclonus epilepsie |

17.2.1. Eerste keus medicatie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

17.2.2. Tweede keus medicatie |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.2.3. Wanneer staken? |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.3. Rolandische epilepsie |

17.3.1. Behandeling geïndiceerd? |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

17.3.2. Eerste keus medicatie |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.3.3. Tweede keus medicatie |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.4. Panayiotopoulos syndroom |

17.4.1. Behandeling geïndiceerd? |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

17.4.2. Eerste keus medicatie |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.4.3. Tweede keus medicatie |

2013 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

17.5. Koortsconvulsies |

17.5.1. Preventieve medicatie |

2015 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

17.5.2. Onderzoek bij recidiven |

2017 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

18. Oudere patiënten |

|||||

|

18.1. Diagnostiek |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

18.2. Behandeling |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

19. Verstandelijke beperking |

|||||

|

19.1. Diagnostiek |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

19.2. Behandeling |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

20. Zwangerschap en hormonen |

|||||

|

20.1. Anti-epileptica en hormonale anticonceptie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

20.2. Anti-epileptica en zwangerschap |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

20.3. Anti-epileptica en borstvoeding |

2018 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

21. Beroerte |

|||||

|

21.1. Profylactische behandeling |

2015 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

21.2. Behandeling na acuut symptomatische aanval |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

21.3. Behandeling na laat symptomatische aanval |

2017 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

21.4. Welk anti-epilepticum bij beroerte |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

22. Oncologie |

|||||

|

22.1. Profylactische behandeling |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

2022: Twee modules compleet herzien |

|

|

22.2. Welk anti-epilepticum |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

||

|

23. Psychogene niet-epileptische aanvallen |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

24. Aanvalsdetectie |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

25. SUDEP |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

26. Begeleiding |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 5 jaar |

|

|

|

27. Organisatie van zorg |

|||||

|

27.1. Welke functies in welke lijn |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

|

27.2. Wanneer verwijzen |

2020 |

2022 |

Na 3 jaar |

|

|

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

De epilepsiepatiënt in Nederland op eenduidige en wetenschappelijk onderbouwde wijze diagnosticeren en behandelen. Ter ondersteuning van de richtlijngebruiker wordt - daar waar relevant - verwezen naar de module Informatie voor patiënten. De inhoud van de patiënteninformatie valt buiten verantwoordelijkheid van de werkgroep.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met epilepsie.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2022 een multidisciplinair cluster ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met epilepsie.

De richtlijn wordt vanaf 2013 jaarlijks geactualiseerd. De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn. De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname. Eventuele mutaties in de werkgroepsamenstelling vinden plaats in overleg met de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie, de werkgroep en de betreffende beroepsvereniging. Nieuwe leden dienen te allen tijden gemandateerd te worden door de betreffende beroepsvereniging. De werkgroep wordt ondersteund door adviseurs van het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten en door een voorlichter van het Epilepsiefonds.

Clusterstuurgroep

- Prof. dr. H.J.M. Majoie (voorzitter), neuroloog, Academisch Centrum voor Epileptologie Kempenhaeghe/ Maastricht UMC+, Heeze en Maastricht

- Drs. M.H.G. Dremmen, radioloog, Erasmus MC Rotterdam

- Dr. P. Klarenbeek, neuroloog, Zuyderland Medisch Centrum, Heerlen

- Dr. J. Nicolai, kinderneuroloog, Academisch Centrum voor Epileptologie Kempenhaeghe/Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht

- Dr. B. Panis, kinderneuroloog, Maastricht UMC+, Maastricht (betrokken tot 16-3-2021)

- Dr. C.M. Delsman-van Gelder, kinderneuroloog, RadboudUMC, Nijmegen (betrokken vanaf 01-01-2022)

- Dr. P. van Vliet, neuroloog/intensivist, Haaglanden Medisch Centrum, Den Haag

- Drs. R. van Vugt, anesthesioloog, Sint Maartens Kliniek, Nijmegen

Clusterexpertisegroep

- Dr. J.A.F. Koekkoek, neuroloog, LUMC, Leiden

- Dr. J. Reijneveld, neuroloog en Universitair Hoofddocent, SEIN en Amsterdam UMC

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J. Buddeke senior adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten Utrecht

- Dr. C.T.J. Michels adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten Utrecht

- Dr. M.M.J. van Rooijen, adviseur Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten Utrecht

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle clusterleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Stuurgroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Majoie* |

Functie: Neurologie Werkgever: Academisch Centrum voor Epileptologie Kempenhaeghe, Maastricht UMC+ |

Relevante commissies

|

Lopende onderzoek- en zorginnovatieprojecten (anders dan contract research) worden gefinancierd uit Erasmusplus, ZonMW, Nationaal epilepsiefonds, stichting vrienden van

Incidenteel financiële ondersteuning aan stichting Kempenhaeghe voor organisatie refereeravonden en workshops/symposia (telkens volgens geldende wet en |

Geen actie |

|

Dremmen |

Functie: Kinderradioloog met subspecialisatie kinderneuroradiologie |

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Klarenbeek |

Functie: Neuroloog Werkgever: Zuyderland te Heerlen/Sittard (vrijgevestigd) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Nicolai |

Functie: Kinderneuroloog Werkgever: Maastricht UMC+. Tevens gedetacheerd/ werkzaam in Kempenhaeghe, Heeze; St Jansgasthuis, Weert; Elkerliek, Helmond en Viecuri, Venlo. |

Coördinator Sepion beginnerscursus; vergoeding wordt door Sepion naar AMBI goed doel gestort. Tevens betrokken bij Sepion gevorderden cursus en AVG cursus; vergoeding wordt door Sepion naar AMBI goed doel gestort. |

Boegbeeldfunctie bij een patiënten- of beroepsorganisatie |

Geen actie |

|

Panis |

Functie: Kinderarts, fellow metabole ziekten. Werkgever: Maastricht UMC+ 0.8fte, hiervan 0.2fte gedetacheerd in Radboudumc. |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie. Betrokken tot 16-03-2021. |

|

Van Vliet |

Functie: Intensivist Werkgever: Haaglanden Medisch Centrum te Den Haag |

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Vugt |

Functie: Anesthesioloog Werkgever: Sint Maartenskliniek te Nijmegen |

Lid commissie kwaliteitsdocumenten NVA (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Expertisegroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Altinbas |

Functie: Neuroloog-kinderneuroloog |

Lid intern werkgroep epilepsie en genetica SEIN (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Balvers |

Functie: Neuroloog (Behandeling van patiënten met epilepsie; klinisch, poliklinisch en in woonzorg) |

|

|

Mogelijk belangen bij Hoofdpijn. Geen restrictie voor Epilepsie. |

|

De Bruijn |

Functie: neuroloog in opleiding Werkgever: ETZ Tilburg |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Eshuis |

Functie: AIOS Spoedeisende geneeskunde Werkgever: Catharina Ziekenhuis te Eindhoven |

APLS instructeur candidate, Stichting Spoedeisende Hulp bij Kinderen (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Hofman |

Functie: Radioloog Werkgever: Maastricht UMC+ (1.0fte) |

Voorzitter interne werkgroep epilepsie en genetica SEIN (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Jenniskens |

Functie: Community manager bij EpilepsieNL (voor 1 maart 2021: Epilepsiefonds en Epilepsie Vereniging Nederland (EVN)): 0.8fte |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koekkoek |

Functie: Neuroloog Werkgever: Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum (0.8fte), Haaglanden Medisch Centrum (0.2fte) |

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Lazeron |

Functie: Neuroloog, wetenschappelijk onderzoeker Werkgever: neuroloog - Academisch centrum Epileptologie Kempenhaeghe Maastricht UMC+ (voltijds). |

CMIO bij Kempenhaeghe als gespecificeerd onderdeel van de functie bij Kempenhaeghe |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Leijten |

Functie: neuroloog Werkgever: UMC Utrecht |

Adviseur LivAssured en ProLira (onbetaald). |

|

Restrictie ten aanzien van besluitvorming met betrekking tot appartaren die aanvallen detecteren (e.g. Nightwatch®, DeltaScan®). |

|

Masselink |

Functie: Ziekenhuisapotheker Werkgever: Medisch Spectrum Twente |

Lid werkgroep Neurologische aandoeningen (inclusief gedrag) Horizonscan Geneesmiddelen, Zorginstituut Nederland (onbetaald). |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Reijneveld |

Functie: Neuroloog, Universitair Hoofddocent

Werkgever: 0.8fte Stichting Epilepsie Instellingen Nederland (SEIN) te Heemstede, 0.2fte Universitair Hoofddocent, afdeling Neurologie, Amsterdam UMC te Amsterdam. |

Voorzitter (per september 2020) Quality of Life Group van de European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ronner |

Functie: Neuroloog Werkgever: 0.8fte Amsterdam UMC |

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Schijns |

Functie: Neurochirurg met specialisatie Epilepsiechirurgie en Neuro-oncologische Chirurgie |

Chairman SectionFunctional Neurosurgery, European Association of Neurosurgical Societies (EANS): onbetaald |

Principal Invetigator (PI) EpiUltra studie. Grantverstrekker Epilepsiefonds Nederland |

Geen actie |

|

Snoeijen |

Functie: Arts Verstandelijk Gehandicapten Werkgever: Kemenhaeghe, fulltime |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Thijs |

Stichting Epilepsie Instellingen Nederland (1.0 fte) |

Geen |

|

Restrictie ten aanzien van besluitvorming met betrekking tot appartaren die aanvallen detecteren (e.g. Nightwatch®). |

|

Tousseyn |

Academisch Centrum voor Epileptologie (ACE) Kempenhaeghe/Maastricht UMC+, locatie Heeze |

Participeer in landelijke werkgroep Epilepsiechirurgie en de ACE-Werkgroep Epilepsiechirurgie |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Uiterwijk |

Functie: Epileptoloog Werkgever: Academisch Centrum voor Epileptologie Kempenhaeghe |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van 't Hof |

Functie: neuroloog Werkgever: SEIN (Stichting Epilepsie Instellingen Nederland) |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Tuijl |

Functie: Neuroloog |

|

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Tolboom |

Functie: Nucleair geneeskundige Werkgever: UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Verbeek |

Functie: Klinisch geneticus Werkgever: UMC Utrecht |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vlooswijk |

Functie: Neuroloog Werkgever: Maastricht UMC+ |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Wegner |

Functie: Neuroloog Werkgever: Stichting Epilepsie instellingen Nederland (SEIN) |

Voorts heb ik geen betaalde nevenwerkzaamheden |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door de afvaardiging van EpilepsieNL in het cluster. De verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodule is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan EpilepsieNL en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijnmodule is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers, 2010).

Need-for-update, prioritering en uitgangsvragen

Tijdens de need-for-update fase inventariseerde het cluster de geldigheid van de modules binnen het cluster. Naast de betrokken wetenschappelijke verenigingen en patiëntenorganisaties zijn hier ook andere stakeholders voor benaderd in februari 2021.

Per module is aangegeven of deze geldig is, kan worden samengevoegd met een andere module, obsoleet is en kan vervallen of niet meer geldig is en moet worden herzien. Ook was er de mogelijkheid om nieuwe onderwerpen voor modules aan te dragen die aansluiten bij één (of meerdere) richtlijn(en) behorend tot het cluster. De modules die door één of meerdere partijen werden aangekaart als ‘niet geldig’ zijn meegegaan in de prioriteringsfase. Deze module is geprioriteerd door het cluster.

Voor de geprioriteerde modules zijn door de het cluster concept-uitgangsvragen herzien of opgesteld en definitief vastgesteld.

Uitkomstmaten

Na het opstellen van de zoekvraag behorende bij de uitgangsvraag inventariseerde het cluster welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. Hierbij werd een maximum van acht uitkomstmaten gehanteerd. Het cluster waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde het cluster tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Methode literatuursamenvatting

Een uitgebreide beschrijving van de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur is te vinden onder ‘Zoeken en selecteren’ onder Onderbouwing. Indien mogelijk werd de data uit verschillende studies gepoold in een random-effects model [Review Manager 5.4] werd gebruikt voor de statistische analyses. De beoordeling van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs wordt hieronder toegelicht.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/). De basisprincipes van de GRADE-methodiek zijn: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van de bewijskracht per uitkomstmaat op basis van de acht GRADE-domeinen (domeinen voor downgraden: risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias; domeinen voor upgraden: dosis-effect relatie, groot effect, en residuele plausibele confounding).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie, in het bijzonder de mate van zekerheid dat de literatuurconclusie de aanbeveling adequaat ondersteunt (Schünemann, 2013; Hultcrantz, 2017).

| GRADE | Definitie |

| Hoog |

|

| Redelijk |

|

| Laag |

|

| Zeer laag |

|

Bij het beoordelen (graderen) van de kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs in richtlijnen volgens de GRADE-methodiek spelen grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming een belangrijke rol (Hultcrantz, 2017). Dit zijn de grenzen die bij overschrijding aanleiding zouden geven tot een aanpassing van de aanbeveling. Om de grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming te bepalen moeten alle relevante uitkomstmaten en overwegingen worden meegewogen. De grenzen voor klinische besluitvorming zijn daarmee niet één op één vergelijkbaar met het minimaal klinisch relevant verschil (Minimal Clinically Important Difference, MCID). Met name in situaties waarin een interventie geen belangrijke nadelen heeft en de kosten relatief laag zijn, kan de grens voor klinische besluitvorming met betrekking tot de effectiviteit van de interventie bij een lagere waarde (dichter bij het nuleffect) liggen dan de MCID (Hultcrantz, 2017).

Netwerk meta-analyse

Voor de beoordeling van de bewijskracht uit een netwerk meta-analyse (NMA) wordt gebruik gemaakt van de CINeMA-tool (Nikolakopoulou, 2020; Papakonstantinou, 2020). Met deze tool wordt op basis van een analyse in R de effectschattingen berekend. Voor het beoordelen van de bewijskracht, op basis van de berekende effectschattingen, worden zes domeinen geëvalueerd, namelijk Risk-of-Bias, publicatiebias, indirectheid, imprecisie, heterogeneteit and incoherentie. Voor het opstellen van de conclusies zijn principes van de GRADE working group gebruikt op basis van grenzen van klinische besluitvorming (Brignardello-Petersen, 2020).

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals aanvullende argumenten uit bijvoorbeeld de biomechanica of fysiologie, waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten, kosten (middelenbeslag), aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Deze aspecten zijn systematisch vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’ en kunnen (mede) gebaseerd zijn op expert opinion. Hierbij is gebruik gemaakt van een gestructureerd format gebaseerd op het evidence-to-decision framework van de internationale GRADE Working Group (Alonso-Coello, 2016a; Alonso-Coello 2016b). Dit evidence-to-decision framework is een integraal onderdeel van de GRADE methodiek.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door het cluster wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk (Agoritsas, 2017; Neumann, 2016). De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen. Het cluster heeft bij elke aanbeveling opgenomen hoe zij tot de richting en sterkte van de aanbeveling zijn gekomen.

In de GRADE-methodiek wordt onderscheid gemaakt tussen sterke en zwakke (of conditionele) aanbevelingen. De sterkte van een aanbeveling verwijst naar de mate van zekerheid dat de voordelen van de interventie opwegen tegen de nadelen (of vice versa), gezien over het hele spectrum van patiënten waarvoor de aanbeveling is bedoeld. De sterkte van een aanbeveling heeft duidelijke implicaties voor patiënten, behandelaars en beleidsmakers (zie onderstaande tabel). Een aanbeveling is geen dictaat, zelfs een sterke aanbeveling gebaseerd op bewijs van hoge kwaliteit (GRADE gradering HOOG) zal niet altijd van toepassing zijn, onder alle mogelijke omstandigheden en voor elke individuele patiënt.

| Implicaties van sterke en zwakke aanbevelingen voor verschillende richtlijngebruikers | ||

| Sterke aanbeveling | Zwakke (conditionele) aanbeveling | |

| Voor patiënten | De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen en slechts een klein aantal niet. | Een aanzienlijk deel van de patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kiezen, maar veel patiënten ook niet. |

| Voor behandelaars | De meeste patiënten zouden de aanbevolen interventie of aanpak moeten ontvangen. | Er zijn meerdere geschikte interventies of aanpakken. De patiënt moet worden ondersteund bij de keuze voor de interventie of aanpak die het beste aansluit bij zijn of haar waarden en voorkeuren. |

| Voor beleidsmakers | De aanbevolen interventie of aanpak kan worden gezien als standaardbeleid. | Beleidsbepaling vereist uitvoerige discussie met betrokkenheid van veel stakeholders. Er is een grotere kans op lokale beleidsverschillen. |

Organisatie van zorg

Bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijnmodule is expliciet aandacht geweest voor de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, mankracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van deze specifieke uitgangsvraag zijn genoemd bij de overwegingen. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van zorg.

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijnmodule werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met het cluster. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijnmodule aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door het cluster. De definitieve richtlijnmodule werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt)organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Agoritsas T, Merglen A, Heen AF, Kristiansen A, Neumann I, Brito JP, Brignardello-Petersen R, Alexander PE, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Guyatt GH. UpToDate adherence to GRADE criteria for strong recommendations: an analytical survey. BMJ Open. 2017 Nov 16;7(11):e018593. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018593. PubMed PMID: 29150475; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5701989.

Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Rada G, Rosenbaum S, Morelli A, Guyatt GH, Oxman AD; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: Introduction. BMJ. 2016 Jun 28;353:i2016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. PubMed PMID: 27353417.

Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, Brignardello-Petersen R, Akl EA, Davoli M, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Meerpohl J, Guyatt GH, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016 Jun 30;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. PubMed PMID: 27365494.

Brignardello-Petersen R, Florez ID, Izcovich A, Santesso N, Hazlewood G, Alhazanni W, Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Tomlinson G, Schünemann HJ, Guyatt GH; GRADE working group. GRADE approach to drawing conclusions from a network meta-analysis using a minimally contextualised framework. BMJ. 2020 Nov 11;371:m3900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3900. PMID: 33177059.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna SE, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L; AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010 Dec 14;182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. Review. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Hultcrantz M, Rind D, Akl EA, Treweek S, Mustafa RA, Iorio A, Alper BS, Meerpohl JJ, Murad MH, Ansari MT, Katikireddi SV, Östlund P, Tranæus S, Christensen R, Gartlehner G, Brozek J, Izcovich A, Schünemann H, Guyatt G. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017 Jul;87:4-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.006. Epub 2017 May 18. PubMed PMID: 28529184; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6542664.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/over_richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Neumann I, Santesso N, Akl EA, Rind DM, Vandvik PO, Alonso-Coello P, Agoritsas T, Mustafa RA, Alexander PE, Schünemann H, Guyatt GH. A guide for health professionals to interpret and use recommendations in guidelines developed with the GRADE approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016 Apr;72:45-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.11.017. Epub 2016 Jan 6. Review. PubMed PMID: 26772609.

Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Papakonstantinou T, Chaimani A, Del Giovane C, Egger M, Salanti G. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020 Apr 3;17(4):e1003082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003082. PMID: 32243458; PMCID: PMC7122720.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html.

Papakonstantinou T, Nikolakopoulou A, Higgins JPT, Egger M & Salanti G. CINeMA: Software for semiautomated assessment of the confidence in the results of network meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2020;16:e1080.

Zoekverantwoording

Zoekacties zijn opvraagbaar. Neem hiervoor contact op met de Richtlijnendatabase.