Preventie cognitieve achteruitgang en dementie

Uitgangsvraag

Welke adviezen en/of interventies zijn gewenst ter preventie van cognitieve achteruitgang?

Aanbeveling

Zet geen multicomponent interventie in met als enige doel cognitieve achteruitgang of dementie te voorkomen.

Indien een patiënt verhoogd cardiovasculair risico heeft, raadpleeg de richtlijn ‘Cardiovasculair risicomanagement’ (NHG / NIV / NVVC, 2019). Hou hierbij rekening met patiëntvoorkeuren en het risicoprofiel van de patiënt.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Negen studies hebben het effect geëvalueerd van een multicomponent interventie op cognitief en/of functioneel functioneren bij ouderen. In deze studies is er sprake van een risico op bias en de multicomponent interventie is op verschillende manieren geoperationaliseerd. De bewijskracht voor de uitkomstmaten (cognitieve achteruitgang, dagelijkse activiteiten, dementie, cognitieve stoornis en kwaliteit van leven) en de overall bewijskracht komen daarmee op zeer laag. Op basis van de huidige literatuur kan er geen conclusie worden getrokken dat een multicomponent interventie effectief is als preventie voor cognitieve achteruitgang en dementie. Dit betekent dat nieuwe studies met langdurige follow up (en eenduidige multicomponent interventie) nodig zijn voor meer bewijskracht.

De gevonden studies laten een zeer geringe verbetering cq minder achteruitgang zien op cognitieve testen bij multicomponent interventie, maar dit verschil is niet klinisch relevant. Op meer klinische uitkomstmaten zoals het krijgen van lichte cognitieve stoornissen (MCI) of dementie wordt geen effect gezien. Een recent gepubliceerde observationele follow-up voor een studiecohort opgenomen in de huidige literatuursamenvatting rapporteert ook geen risicoreductie op dementie na een follow-up van 12 jaar (dementie incidentie 11,6 % (oorspronkelijke interventiegroep) vs. 11,9% (oorspronkelijke controlegroep), hazard ratio 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89- 1.10; P = .92) (Hoevenaar-Blom, 2021).

Op grond van epidemiologische studies kunnen we patiënten informeren over welke risicofactoren voor dementie er zijn (Livingston, 2020), maar het is nog onduidelijk of al deze risicofactoren echt een causaal verband hebben met het krijgen van een dementiesyndroom en of het terugbrengen van die risicofactoren het risico op dementie verkleint. Hoewel er in deze module geen specifiek literatuuronderzoek is verricht naar unicomponent interventies, acht het cluster het benoemen van de behandeling van hoge bloeddruk als noemenswaardig. Een recente meta-analyse toonde dat langdurige intensieve behandeling van hypertensie (>2 jaar) bij personen van 55 tot 75 jaar het risico op dementie iets verlaagd (Hughes, 2020; Peters, 2022). Het netto-effect is gering maar consistent, 7.0% versus 7.5% bij een gemiddelde trial follow-up van 4.3 jaar. Hughes (2020) rapporteert odds ratio van 0.93 (95%CI 0.88 tot 0.98); absolute risicoreductie (ARR) 0.39% (95%CI 0.09 tot 0.68%) voor intensieve versus standaard bloeddrukverlaging. Peters (2022) rapporteert odds ratio van 0.87 (95%CI 0.75 tot 0.99) voor vermindering van ontwikkeling van dementie met een bloeddrukverlaging van 10/4 mm Hg ten op zichtte van placebo. Sproviero (2021) en Peters (2021) geven aan dat ondanks heterogeniteit in samples en studieopzet bloeddrukbehandeling wel degelijk veelbelovend is voor vermindering van het risico op dementie en dat aanvullende studies nodig zijn. Het individuele risicoprofiel kan bij verschillen per patient. Er zijn 9 risicofactoren geïdentificeerd, waaronder lage opleiding, overgewicht, hypertensie, slechthorendheid, roken, depressie, fysieke inactiviteit, diabetes en weinig sociale contacten. Een lagere opleiding en sociale klasse komen vaak gecombineerd voor met andere bovengenoemde risicofactoren, zoals diabetes mellitus, overgewicht, hoge bloeddruk, roken, overmatig alcoholgebruik (Livingston, 2020) waarop interventie wel effect zou kunnen geven. Toekomstige studies naar het effect van een multicomponente interventie in subgroepen (o.a. lagere opleiding, lagere sociale klasse), met een langere follow-up duur en vroegtijdige start van interventie (bijvoorbeeld vanaf middelbare leeftijd 40-60 jaar) kunnen beter bewijs opleveren.

De multicomponent interventie is op verschillende manieren geoperationaliseerd door de studies in Den Brok (2022) (zie tabel 1 in de literatuursamenvatting). Alle studies geven leefstijl en zelfmanagement advies in de interventie groep, maar in slechts vier studies is lichaamsbeweging onderdeel van de interventie en in drie daarvan ook nog cognitieve training. Hoewel een hoge kwaliteit van zorg aanwezig was in alle studies, waren de interventies in sommige studies minder intensief. Daarnaast varieerde de duur van de interventies van 12 maanden tot 10 jaar. Daarom kan geen uitspraak worden gedaan over het inzetten op interventies gericht op bepaalde risicofactoren of een bepaalde combinatie van risicofactoren, omdat onduidelijk is of specifieke interventies een groter effect hebben. Ook de vraag hoelang interventies zouden moeten duren en of meer intensieve interventies misschien meer effectief zijn is niet te beantwoorden op basis van deze studies. Denk daarbij aan interventies die een sterkere daling in bloeddruk of cholesterol bereiken, een sterkere gewicht reductie of toename in lichaamsbeweging.

Er is geen eenduidig bewijs dat een multicomponent interventie effect heeft op het cognitief functioneren. Dit hangt mede af hoe het cognitief functioneren in deze studies is gemeten. Grotere overeenstemming over hoe cognitieve achteruitgang beoordeeld moet worden, kan helpen om interventies beter te beoordelen. Hafdi (2021) rapporteert cognitieve achteruitgang aan de hand van neuropsychologische tests (NTB), MoCA en MMSE. Op basis van NTB is er bewijs voor een klein gunstig effect van multicomponent interventies op cognitief functioneren. Echter, dit effect is alleen waargenomen in de studies waarin cognitieve training onderdeel was van de multicomponent interventie en dus wellicht een leereffect voor cognitieve testen in de interventiegroep aanwezig is. Op basis van de MOCA is er zeer lage kwaliteit bewijs voor een klein gunstig effect van multicomponent interventies op cognitief functioneren. Er is geen bewijs voor een effect op de MMSE, de meest gebruikte uitkomstmaat.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en evt. hun verzorgers)

Voor patiënten is het belangrijk om zelf iets te kunnen doen om cognitieve achteruitgang te remmen of zelfs te voorkomen. De patiënt hecht hierbij veel belang aan uitleg over de risicofactoren die geassocieerd zijn met ontwikkeling van dementie. Hierbij is het goed om uit te leggen dat wanneer men aan de slag wil met leefstijl een multicomponent interventie het meest zinvol is en dat de meeste ervaring en hoogste verwachting bestaat ten aanzien van gecombineerde interventies gericht op cardiovasculaire risicofactoren. De verwachting is dat de meeste patiënten positief staan tegenover de inzet van multicomponent interventies gericht op voeding, beweging, behandelen van cardiovasculaire risicofactoren, sociale activiteiten en cognitieve stimulatie (leren van nieuwe vaardigheden, bijvoorbeeld muziek, taal leren).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

De kosten van de multicomponent interventie moeten in een groot deel van de gevallen door de patiënt zelf worden betaald. De meerwaarde voor preventie van dementie en cognitieve achteruitgang is niet aangetoond. Of deze kosten opwegen tegen de (beperkte) gezondheidswinst moet per patiënt worden afgewogen. Bij patiënten met een hoog cardiovasculair risicoprofiel is behandelen volgens CVRM-richtlijn zinvol gezien de wel bewezen risicoreductie op hart- en vaatziekten in het algemeen en het effect wat hierdoor secundair mogelijk op de hersenen verwacht kan worden.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Multicomponent interventies op voeding, beweging, cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en cognitieve training zijn relatief eenvoudig en relatief weinig tijdrovend voor de zorgverlener. Echter gaat het grotendeels om leefstijlinterventies, die veel vragen van zowel de patiënt als diens omgeving. We verwachten meer belemmerende factoren voor personen met geringe gezondheidsvaardigheden, lager inkomen en lage sociale klasse. We weten dat de verandering in leefstijl vaak lastiger is voor deze groepen terwijl de omgeving er minder op is ingericht. Daarnaast worden de kosten vaak niet vergoed en dit is een grotere barrière voor de groepen met een laag inkomen.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

De komende jaren wordt een toename verwacht in het aantal mensen met dementie (Livingston, 2020). Een veel gestelde vraag in de spreekkamer van een patiënt die zich zorgen maakt om dementie te krijgen is: ‘dokter wat kan ik er zelf aan doen om cognitieve achteruitgang te remmen of zelfs te voorkomen?’ Leeftijd is de belangrijkste risicofactor. Belangrijke andere risicofactoren voor het ontwikkelen van dementie zijn hypertensie, diabetes, roken, overmatig alcoholgebruik en onvoldoende lichaamsbeweging (Livingston, 2020). Ondanks dat niet zeker is of elk van deze risicofactoren causaal verbonden is met het ontstaan van dementie, ligt een multicomponent interventie waarbij meerdere risicofactoren tegelijkertijd worden aangepakt op basis van de huidige inzichten het meest voor de hand. Ook omdat deze factoren los van dementie relevant zijn voor de preventie van andere aandoeningen, zoals hart- en vaatziekten. Daarom is er een literatuur search gedaan gericht op multicomponent interventies d.w.z. voeding, beweging, cardiovasculaire risicofactoren en cognitieve training in de preventie van cognitieve achteruitgang.

Conclusies

1. Cognitive decline (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a multicomponent intervention on cognitive decline when compared with placebo in patients at risk for dementia.

Sources: Hafdi, 2021 (including Ngandu 2015; Andrieu 2017; Richard 2019; Komulainen 2010; Lee 2014; Moll 2016; Li 2018; Chen 2020); Den Brok, 2022 |

2. Daily activities (critical)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a multicomponent intervention on daily activities when compared with placebo in patients at risk for dementia.

Sources: Hafdi, 2021 (including Ngandu, 2015; Moll, 2016; Andrieu, 2017; Richard, 2019; Chen, 2020) |

3. Incidence of dementia (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a multicomponent intervention on the incidence of dementia when compared with placebo in patients at risk for dementia.

Sources: Hafdi, 2021 (including Moll, 2016; Espeland, 2017) |

4. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a multicomponent intervention on the incidence of mild cognitive impairment when compared with placebo in patients at risk for dementia.

Source: Hafdi, 2021 (including Espeland, 2017) |

5. Quality of life (important)

|

Very low GRADE |

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of a multicomponent intervention on the quality of life when compared with placebo in patients at risk for dementia.

Source: Hafdi, 2021 (including Strandberg, 2017) |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Hafdi (2021) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis and evaluated the effects of multicomponent interventions on the prevention of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults. A systematic literature search was performed up until 28 April 2021. Studies were included if they 1) were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a double-blinded, single-blinded, open and 'prospective, randomised, open, blinded end-point' (PROBE) design and an outcome of cognitive function or incident dementia, 2) had a follow-up of ≥12 months, 3) had ≥400 participants, 4) participants were ≥50 years of age, 5) included a multicomponent intervention with more than one component (e.g. pharmacological treatment, physical activity, dietary manipulations), but not including two or more drugs targeting the same therapeutic target (e.g. two antihypertensive medications), 6) had a control condition of no intervention, usual care, placebo or any other type of sham intervention, but not single-component interventions intended to reduce dementia risk, 7) assessed cognitive function or incidence of dementia according to any of the validated criteria current at the time of the study. In total nine randomized control trials (RCTs) comprising 18.452 patients were included (Komulainen, 2010; Ngandu, 2015; Richard, 2019; Lee, 2014; Li, 2018; Espeland, 2017; Andrieu, 2017; Moll, 2016; Chen, 2020). Characteristics of the individual studies are summarized in the evidence tables and table 1.

Den Brok (2022) performed a pooled analysis of individual participant data from two parallel RCTs comprising 4162 patients (Andrieu, 2017 n=1680; Moll, 2016 n=3526). Both RCTs were included in Hafdi (2021). Both RCTs examined the effects of a multicomponent intervention on the prevention of cognitive decline in a community-dwelling population free from dementia at baseline and over 70 years of age. The RCTs compared a multicomponent intervention to usual care. Moll (2016) compared two groups (one intervention group, one control group). Andrieu (2017) compared four groups (two intervention groups, two control groups) also containing a comparison of omega-3 capsules to placebo capsules. For the pooled analysis the omega-3 and placebo groups were merged, thus half of the patients in both groups were on (placebo) and the other half were on omega-3 capsules. Outcome measure was cognitive decline, which was measured with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Characteristics of the individual studies are summarized in the evidence tables and table 1.

Table 1. Summary of study characteristics

|

Study |

Population |

Intervention |

Control |

Outcomes |

Follow-up |

|

Hafdi, 2021 |

|||||

|

Komulainen, 2010 |

1410 patients (group 1: 234, group 2: 234, control: 236), 65.9 yrs |

Group 1: aerobic exercise + diet. Group 2: resistance training + diet. |

Oral information with general advice on diet and physical activity. |

Cognitive decline: MMSE |

2 years |

|

Ngandu, 2015 and Strandberg, 2017 (for the outcome quality of life) |

1260 patients (631 intervention, 629 control), 69.3 yrs |

Nutritional advice, physical exercise, and cognitive training with 6 monthly assessments by study nurse. |

Regular health advice. |

Cognitive decline: MMSE and composite score neuropsychological test battery (NTB) Quality of life: Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (RAND-36) Daily activities: multiple Activities of Daily Living related questionnaires. |

2 years |

|

Richard, 2019 |

2724 patients (1389 intervention, 1335 control), 69 yrs High risk population with ≥2 cardiovascular risk factors or a history of cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes. |

Continuous coaching to facilitate self-management of cardiovascular risk factors via internet-based platform with remote support from a coach, goal setting at start, boost-call at 12 months. |

Static platform, similar in appearance, with limited general health information only, without interactive components or a remote coach. |

Cognitive decline: MMSE and composite score neuropsychological test battery (NTB) Daily activities: late life function and disability instrument. |

18 months |

|

Lee, 2014 |

1115 patients (group 1: 215, group 2: 241, group 3: 211, group 4: 236, control: 212), 77.1 yrs |

Group 1: every two months telephonic lifestyle review. Group 2: monthly telephonic lifestyle review plus educational items. Group 3: every two months health worker visit to review lifestyle. Group 4: every two months health worker visit to review lifestyle plus behavioural reinforcement through rewards. |

Lifestyle advice. |

Cognitive decline: MMSE |

18 months |

|

Li, 2018 |

510 patients (group 1: 116, group 2: 209 control group 1: 38, control group 2: 147), 45.6 yrs High risk population of mine workers with hypertension (SPB > 140, DBP > 90 or taking antihypertensive drugs 2 weeks before the study) |

Group 1: lifestyle advice plus medication. Group 2: lifestyle advice only. |

Group 1: medication without lifestyle advice. |

Cognitive decline: MoCA |

2 years |

|

Espeland, 2017 |

5145 patients (2570 intervention, 2575 control), 58.8 yrs High risk population with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (≥ 27 kg/m2 if currently taking insulin), Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

Lifestyle: 7% weight loss goal with calorie goals and physical activities support. |

Three group educational/social support sessions each year for 4 years after randomizations of the last volunteer. |

Cognitive decline: modified version of the MMSE (3MSE, 100-point scale), Incidence of dementia Mild Cognitive Impairment |

10-13 years |

|

Andrieu, 2017* |

1680 patients (group 1: 417, group 2: 420 control: 420), 75.3 yrs High risk population with at least one of the following: spontaneous memory complaint expressed to their physician, limitation in one instrumental activity of daily living, or slow gait speed (≤ 0.8 meter/second, or more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metre). |

Group 1: Omega-3 capsules and multidomain intervention with cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and nutrition. Group 2: Placebo capsules and multidomain intervention with cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and nutrition. |

Group 1: Daily placebo capsules (vs omega-3). Group 2: Usual care (vs multidomain). |

Cognitive decline: MMSE and composite score neuropsychological test battery (NTB) Daily activities: Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Prevention Instrument (ADCSADLPI) |

36 months |

|

Moll, 2016* |

3526 patients (1890 intervention, 1636 control), 74.5 yrs |

Nurse-led multidomain cardiovascular care (lifestyle advice and medication). |

Usual care. |

Cognitive decline: MMSE Incidence of dementia Daily activities: Amsterdam Linear Disability Scale |

6-8 years |

|

Chen, 2020 |

1082 patients (549 intervention, 533 control), 75.1 yrs High risk population with subjective memory impairment and/or loss of ≥ 1 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and/or timed 6-mertre walk speed ≤ 1 metre/second |

Physical training and advice on managing/preventing chronic disease by physician. |

Usual care, including offering conventional health education via three monthly telephone calls. |

Cognitive decline: MoCA Daily activities: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

12 months |

|

Den Brok, 2022 |

|||||

|

Den Brok, 2022 |

4162 patients (median age 74 yrs) |

Andrieu, 2017 Group 1: Omega-3 capsules and multidomain intervention. Group 2: Placebo capsules and multidomain intervention.

Moll, 2016 Nurse-led multidomain cardiovascular care (lifestyle advice and medication). |

Andrieu 2017 Usual care (vs multidomain), with half participants taking placebo capsules and other half omega-3 capsules.

Moll, 2016 Usual care. |

Cognitive decline: MMSE |

3-4 years |

|

*Included in pooled analysis of Den Brok (2022). |

|||||

Results

1. Cognitive decline (critical)

Both studies (Hafdi, 2021; Den Brok, 2022) reported on cognitive decline, using 9 RCTs (Komulainen, 2010; Ngandu, 2015; Richard, 2019; Lee, 2014; Li, 2018; Espeland, 2017; Andrieu, 2017; Moll, 2016; Chen, 2020). The outcome cognitive decline was assessed with three different measures:

- Composite score from a neuropsychological test battery (NTB)

- Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

Composite score from a neuropsychological test battery (NTB)

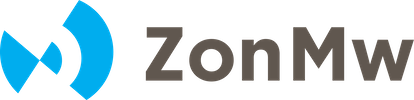

For the comparison between multicomponent intervention and control, three studies (Ngandu, 2015; Andrieu, 2017; Richard, 2019) with 4617 participants were combined by Hafdi (2021) in a meta-analysis. Analyses showed that the mean difference in the NTB score between the multicomponent-group (n=2482) and the control-group (n=2135) was 0.03 (95%CI 0.01 to 0.06) favouring multicomponent intervention, see Figure 1. This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 1 Results of the meta-analysis for the effect of a multicomponent intervention on cognitive decline assessed by a neuropsychological test battery (NTB).

Two studies (Ngandu, 2015; Andrieu, 2017) performed subgroup analysis for baseline cognitive status based on MMSE score (Andrieu, 2017: <30 points, Ngandu, 2015: <26 points) and were combined in a meta-analysis for 2331 patients by Hafdi (2021). Analyses showed that the mean difference in the NTB score favoured multicomponent intervention in the low baseline cognition subset 0.06 (95%CI 0.01 to 0.11; 1414 participants), but not in participants with a high baseline cognition (mean difference: 0.01, 95%CI -0.01 to 0.04; 917 participants). This difference was not clinically relevant.

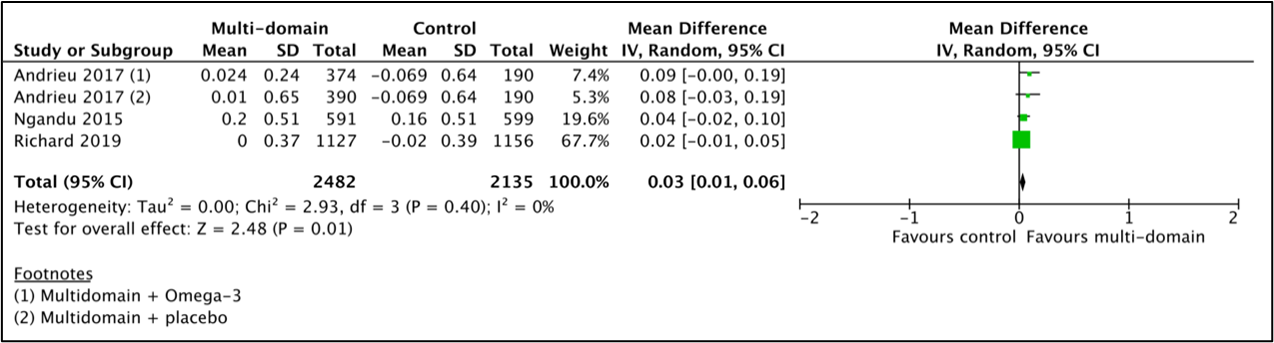

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

For the comparison between multicomponent intervention and control, four studies (Ngandu, 2015; Andrieu 2017; Richard, 2019) from Hafdi (2021) were combined with Den Brok (2022) in a meta-analysis of 8891 participants. Analyses showed a mean difference between multicomponent-group (n=4774) and the control-group (n=4117) was 0.01 (95%CI -0.06 to 0.08), see Figure 2. This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 2 Results of the meta-analysis for the effect of a multicomponent intervention on cognitive decline assessed by MMSE.

Espeland (2017) from Hafdi (2021) was not included in the MMSE meta-analysis as it used a modified version of the MMSE (3MSE, 100-point scale). This study also did not observe a clinically relevant difference in cognitive decline measured with the 3MSE (mean difference: 0.06 point, 95%CI -0.31 to 0.44).

Den Brok (2022) performed a subgroup analysis for baseline cognition based on MMSE < 26 at baseline. In the multicomponent intervention group, the MMSE declined less in those with MMSE <26 at baseline (n=250; mean difference: 0.84 point, 95%CI 0.15 to 1.54) compared to those with MMSE ≥26 at baseline (n=3454; mean difference: -0.03, 95%CI -0.12 to 0.06). This difference was not clinically relevant.

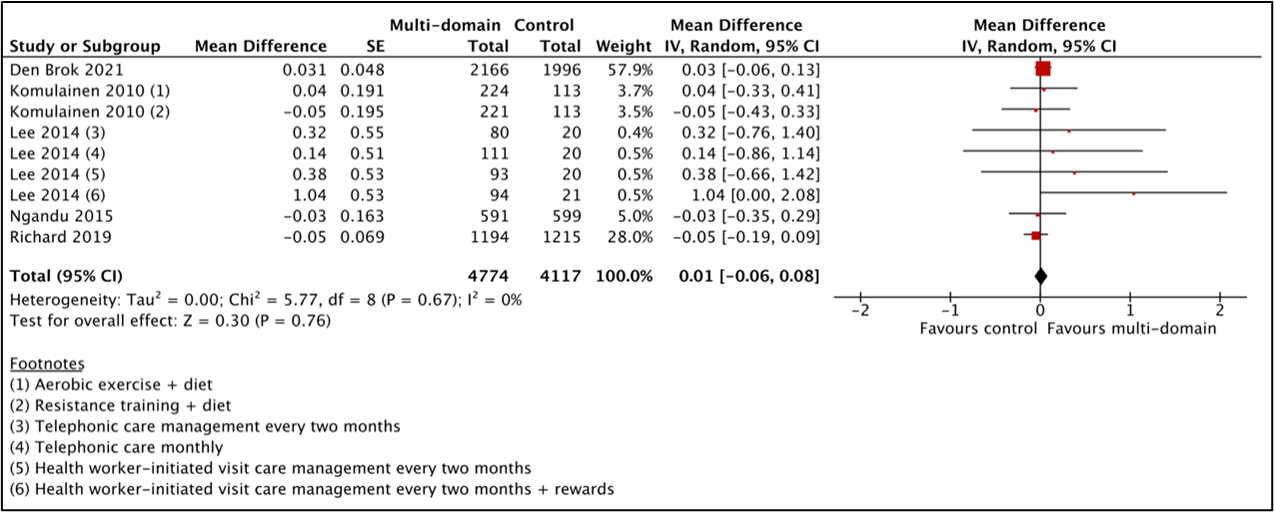

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)

For the comparison between multicomponent intervention and control, two studies (Li, 2018; Chen, 2020) with 1554 participants were combined by Hafdi (2021) in a meta-analysis. Both studies have severe study limitations with issues around randomization, trial registration and statistical analyses (described in more detail in the evidence table). Analyses showed that the mean difference between the multicomponent-group (n=874) and the control-group (n=680) was 0.76 (95%CI 0.05 to 1.46) favouring multicomponent intervention, see Figure 3. This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 3 Results of the meta-analysis for the effect of a multicomponent intervention on cognitive decline assessed by MoCA.

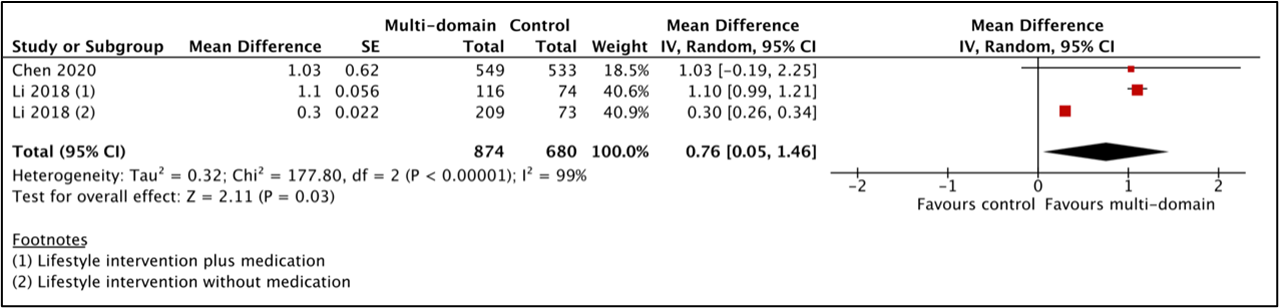

2. Daily activities (critical)

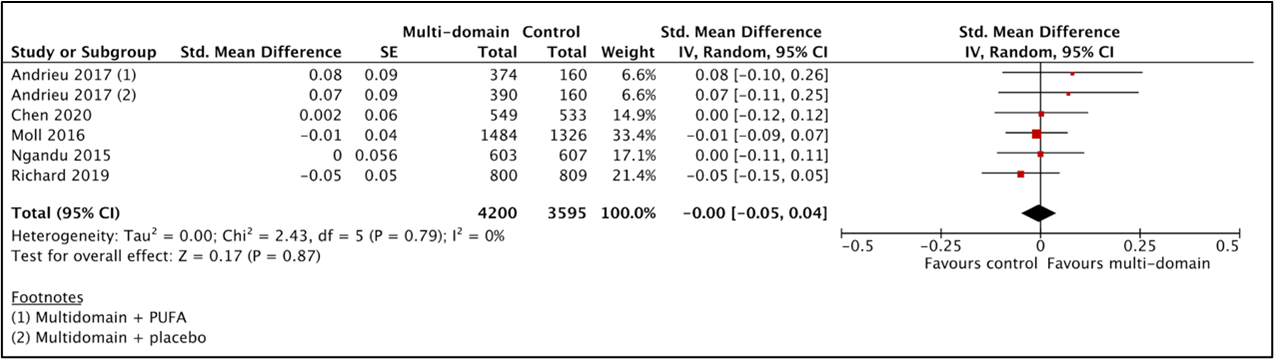

For the comparison between multicomponent intervention and control, five studies (Andrieu, 2017; Chen, 2020; Moll, 2016; Ngandu, 2015; Richard, 2019) with 7795 participants were combined by Hafdi (2021) in a meta-analysis. Analyses showed that the standardized mean difference between the multicomponent-group (n=4200) and the control-group (n=3595) was -0.00 (95%CI -0.05 to 0.04), see Figure 4. This difference was not clinically relevant.

Figure 4 Results of the meta-analysis for the effect of a multicomponent intervention on daily activities.

3. Incidence of dementia (important)

For the comparison between multicomponent intervention and control, two studies (Espeland 2017, Moll 2016) with 7256 participants were combined by Hafdi (2021) in a meta-analysis. Analyses showed that dementia was present in 155 out of 3771 (4.1%) patients in the multicomponent-group and in 146 out of 3485 (4.2%) patients in the control-group, resulting in a risk ratio of 0.94 (95%CI 0.76 to 1.18). This difference was not clinically relevant.

4. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment (important)

One study (Espeland, 2017) from Hafdi (2021) evaluated the effect of a multicomponent intervention on MCI incidence in 3802 patients. In the intervention-group in 122 out of 1918 patients (6.4%) and in the control-group 124 out of 1884 patients (6.6%) were diagnosed with MCI. This resulted in a risk ratio of 0.97 (95%CI 0.76 to 1.23). This difference was not clinically relevant.

5. Quality of life (important)

One study (Strandberg, 2017) from Hafdi (2021) evaluated the effect of a multicomponent intervention on quality of life in 1260 patients. The standardized mean difference in RAND-36 (SF-36) score between the multicomponent-group (n=631) and the control-group (n=629) was 0.18 for general health, 0.013 for physical function, 0.08 for role physical, 0.05 for role mental, 0.03 for vitality, 0.02 for mental health, 0.02 for social function and 0.01 for bodily pain, all favouring the multicomponent-group. For none of the RAND-36 components the difference between the groups was clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. The level of evidence regarding the outcome cognitive decline started at high but was downgraded by three levels to very low due to study limitations including lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and heterogeneity between studies (-1, inconsistency).

2. The level of evidence regarding the outcome daily activities started at high but was downgraded by three levels to very low due to study limitations including lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias (-1; risk of bias), heterogeneity between studies and conflicting results between studies (-2, inconsistency).

3. The level of evidence regarding the outcome incidence of dementia started at high but was downgraded by three levels to very low due to study limitations including lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and heterogeneity between studies (-1, inconsistency).

4. The level of evidence regarding the outcome mild cognitive impairment started at high but was downgraded by three levels to very low due to study limitations lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel (-1, risk of bias), imprecision (-1, confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference and the inclusion of patients from only one study) and all study participants had a history of diabetes type 2 which means there is uncertain external validity to other populations (indirectness, -1).

5. The level of evidence regarding the outcome quality of life started at high but was downgraded by three levels to very low due to study limitations including lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias (-2; risk of bias) and imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference and the inclusion of patients from only one study).

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question: What are the effects of multicomponent interventions intended to improve cognitive/functional course in patients with cognitive symptoms, without pre-existing cognitive disorders, aged 50 years and above?

P: patients with cognitive symptoms, without pre-existing cognitive disorders, aged 50 years and above

I: multicomponent intervention with more than one component (e.g. pharmacological treatment, physical activity, dietary manipulations) with duration at least 12 months

C: placebo, no intervention/usual care, waiting list

O: cognitive decline, daily activities, incidence of dementia, incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), well-being/quality of life

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered cognitive decline and a reduction in activities of daily living (henceforward: Daily Activities) as critical outcome measures for decision making; and incidence of dementia, incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as well as well-being/quality of life as important outcome measures for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies.

Per outcome, the working group defined the following differences as minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

- Cognitive decline: RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous); 0.5 SD (continuous)

- Activities of daily living: RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous); 0.5 SD (continuous)

- Incidence of dementia: RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous)

- Incidence of mild cognitive impairment: RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous)

- Well-being/quality of life: RR ≤0.8 or ≥1.25 (dichotomous); 0.5 SD (continuous)

Search and select (Methods)

The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until 17 January 2022. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 383 hits. Studies for this module were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic reviews (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available), randomized controlled trials, or observational comparative studies,

- full-text English language publication,

- adults aged ≥ 50 years,

- studies including ≥ 20 (ten in each study arm) patients, and

- studies according to the PICO.

A total of 207 studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening. After reading the full text, 205 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods) and 2 studies were included.

Results

Two studies were included in the analysis of the literature, one is a systematic review including nine studies and the other is a pooled analysis for two of the nine studies. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- den Brok MGHE, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Coley N, Andrieu S, van Dalen J, Meiller Y, Guillemont J, Brayne C, van Gool WA, Moll van Charante EP, Richard E. The Effect of Multidomain Interventions on Global Cognition, Symptoms of Depression and Apathy - A Pooled Analysis of Two Randomized Controlled Trials. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(1):96-103. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2021.53. PMID: 35098979.

- Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Brayne C, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Costafreda SG, Dias A, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Ogunniyi A, Orgeta V, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020 Aug 8;396(10248):413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. Epub 2020 Jul 30. PMID: 32738937; PMCID: PMC7392084.

- Hafdi M, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Richard E. Multi-domain interventions for the prevention of dementia and cognitive decline. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Nov 8;11(11):CD013572. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013572.pub2. PMID: 34748207; PMCID: PMC8574768.

- Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Richard E, Moll van Charante EP, van Wanrooij LL, Busschers WB, van Dalen JW, van Gool WA. Targeting Vascular Risk Factors to Reduce Dementia Incidence in Old Age: Extended Follow-up of the Prevention of Dementia by Intensive Vascular Care (preDIVA) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2021 Dec 1;78(12):1527-1528. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.3542. Erratum in: JAMA Neurol. 2022 Jan 1;79(1):93. Erratum in: JAMA Neurol. 2022 Jan 10;: PMID: 34633434; PMCID: PMC8506299.

- Hughes D, Judge C, Murphy R, Loughlin E, Costello M, Whiteley W, Bosch J, O'Donnell MJ, Canavan M. Association of Blood Pressure Lowering With Incident Dementia or Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020 May 19;323(19):1934-1944. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4249. PMID: 32427305; PMCID: PMC7237983.

- Sproviero W, Winchester L, Newby D, Fernandes M, Shi L, Goodday SM, Prats-Uribe A, Alhambra DP, Buckley NJ, Nevado-Holgado AJ. High Blood Pressure and Risk of Dementia: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study in the UK Biobank. Biol Psychiatry. 2021 Apr 15;89(8):817-824. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.12.015. Epub 2020 Dec 27. PMID: 33766239.

- Peters R, Breitner J, James S, Jicha GA, Meyer PF, Richards M, Smith AD, Yassine HN, Abner E, Hainsworth AH, Kehoe PG, Beckett N, Weber C, Anderson C, Anstey KJ, Dodge HH. Dementia risk reduction: why haven't the pharmacological risk reduction trials worked? An in-depth exploration of seven established risk factors. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2021 Dec 8;7(1):e12202. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12202. PMID: 34934803; PMCID: PMC8655351.

- Peters R, Xu Y, Fitzgerald O, Aung HL, Beckett N, Bulpitt C, Chalmers J, Forette F, Gong J, Harris K, Humburg P, Matthews FE, Staessen JA, Thijs L, Tzourio C, Warwick J, Woodward M, Anderson CS; Dementia rIsk REduCTion (DIRECT) collaboration. Blood pressure lowering and prevention of dementia: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022 Oct 25:ehac584. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac584. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36282295.

Evidence tabellen

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

|

Study

|

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1 |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2 |

Description of included and excluded studies?3 |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4 |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5 |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6 |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7 |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8 |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9 |

|

Hafdi, 2021 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes, although the type of multicomponent intervention per study varies. Some studies also include medication, while others only include lifestyle interventions. |

Unclear, cannot be formally ruled out as the authors could not assess publication bias in funnel plot because of the limited number of identified studies |

Yes |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs)

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table etc.)

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (e.g. Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (e.g., funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (e.g., Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included, score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) |

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Hafdi 2021

[individual study characteristics deduced from Hafdi 2021] |

SR and meta-analysis of 9 parallel RCTs.

Literature search up to 28 April 2021

A: Komulainen, 2010 (DRs extra) B: Ngandu, 2015 (Finger) C: Richard, 2019 (Hatice 2019) D: Lee, 2014 E: Li, 2018 F: Espeland, 2017 (Look AHEAD 2017) G: Andrieu, 2017 France placebo-randomized superiority trial with four parallel groups including 30 memory centers (MAPT 2017) H: Moll, 2016 Netherlands open-label cluster RCT including 116 general practices (preDIVA 2016) I: Chen, 2020 (Taiwan Health 2020)

Three studies were carried out in a community-based setting (A,D,H) and six studies were carried out via a healthcare facility.

One study (Espeland, 2017) is at unclear risk of bias as the study was partially funded by commercial funding sources but did not explicitly state the exact role of their funding sources. |

Inclusion criteria SR: double-blinded, single-blinded, open and 'prospective, randomised, open, blinded end-point' (PROBE) design studies with a minimum follow-up of 12 months and 400 or more participants with participants over 50 years of age; 9 studies included.

Participants were over 50 years of age, including unselected and high-risk populations (with known risk factors for dementia and/or subjective cognitive symptoms or cognitive impairment not fulfilling criteria for a dementia diagnosis).

N, mean age A: 1410 patients (group 1: 234, group 2: 234, control: 236), 65.9 yrs B: 1260 patients (631 intervention, 629 control), 69.3 yrs C: Total: 2724 (1389 intervention, 1335 control), 69 yrs D: Total: 1115 (intervention 1: 215, intervention 2: 241, intervention 3: 211, intervention 4: 236, Control: 212), 77.1 yrs E: Total 510 (Intervention: group 1: 116, group 2: 209 Control: group 1: 38, group 2: 147), 45.6 yrs F: Total: 5145 (intervention: 2570, control: 2575), 58.8 yrs G: Total: 1680 (Intervention: Group 1: 417, group 2: 420 Control: 420), 75.3 yrs H: Total: 3526 (Intervention: 1890, Control: 1636), 74.5 yrs I: Total: 1082 (Intervention: 549 Control: 533), 75.1 yrs

C, E,F,G&I includes a high risk population C: >=2 cardiovascular risk factors or a history of cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes. E: mine workers with hypertension (SPB > 140, DBP > 90 or taking antihypertensive drugs 2 weeks before the study) F: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (≥ 27 kg/m2 if currently taking insulin), Type 2 diabetes mellitus G: At least one of the following: spontaneous memory complaint expressed to their physician, limitation in one instrumental activity of daily living, or slow gait speed (≤ 0.8 meter/second, or more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metre). I: Subjective memory impairment and/or loss of ≥ 1 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), and/or timed 6-mertre walk speed ≤ 1 metre/second |

Multi-domain interventions with more than one component, not including two or more drugs targeting the same therapeutic target (e.g. two antihypertensive medications) delivered by trained professionals. Major components of modification include, but are not limited to, pharmacological treatment, physical activity, and dietary manipulations.

All nine studies incorporated lifestyle and self-management advice, no study used a predefined pharmacological treatment, four incorporated exercise (A,B,G,I) and three (B,G,I) also delivered cognitive training.

A: Group 1: aerobic exercise + diet. 5 x 60 minutes/week aerobic exercise. 5 individual exercise or nutrition session in 1st year and every 6 months thereafter B: 6 monthly assessments with study nurse. Nutrition: 3 individual and 7-9 group sessions. Physical exer- cise: 1-3/week muscle strength, 2-5/week aerobic. Cognitive training: 10 group, 72 individual sessions. C: Continuous coaching to facilitate self-management of cardiovascular risk factors via intern-based platform with remote support from a coach, goal setting at start, boost-call at 12 months. D: Group 1: every two months telephonic care management (10-15 minutes) reviewing participants' lifestyle behaviour Group 2: monthly telephonic care management and educational items Group 3: every two months health worker-initiated visit care management (15-20 minutes) reviewing participants' lifestyle behaviour Group 4: every two months health worker-initiated visit care management (15-20 minutes) reviewing participants' lifestyle behaviour plus behavioural reinforcement through rewards such as golden medals E: Group 1: (using medication) Health education and behaviour counselling monthly. Regular health seminars and free education material on prevention of hypertension every 3 months. Monthly SMS reminders to improve lifestyle. Monthly phone calls concerning blood pressure and lifestyle Group 2: (not using medication) Health education and behaviour counselling monthly. Regular health seminars and free education material on prevention of hypertension every 3 months. Monthly SMS reminders to improve lifestyle. Monthly phone calls concerning blood pressure and lifestyle F: 7% weight loss goal with targeted daily calorie goals of 1,200– 1,800 according to initial weight and ≥ 175 minutes/week of physical activities such as brisk walking. Intervention sessions occurred weekly at months 1–6 and then tapered to 3 per month for the remainder of the first year, 6 months, and monthly thereafter, with additional support with monthly phone or e-mail contacts. G: Group 1: Two capsules of PUFA daily and 2-hour group sessions focusing on three domains (cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and nutrition) and a preventive consultation (at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months) with a physician to optimise management of cardiovascular risk factors and detect functional impairments. Twelve small group sessions of the multi-domain intervention were done in the first 2 months of the trial. Each session included 60 minutes of cognitive training, 45 minutes of advice about and demonstrations of physical activity and 15 minutes of nutritional advice. Group 2: Two capsules of placebo daily and 2-hour group sessions focusing on three domains (cognitive stimulation, physical activity, and nutrition) and a preventive consultation (at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months) with a physician to optimise management of cardiovascular risk factors and detect functional impairments. Twelve small group sessions of the multi-domain intervention were done in the first 2 months of the trial. Each session included 60 minutes of cognitive training, 45 minutes of ad- vice about and demonstrations of physical activity and 15 minutes of nutritional advice. H: Nurse-led multidomain cardiovascular care (lifestyle advice supported by motivational interviewing techniques and drug treatment for hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus or antithrombotic drugs) I: Four structured 2-hour training sessions in the first month, two during the second, and one in each of the next 10 months. In addition, every 3 or 4 months, some activities were curtailed, and a visiting doctor instead gave a 30 to 60 minutes class on preventing/man- aging chronic disease |

Two studies delivered care as usual via the general practitioner (E,H), one used daily placebo pills and no lifestyle intervention (G), and six gave concise health and lifestyle advice (A-D,F,I).

A: Oral information about general public health advice on diet and physical activity. B: Regular health advice C: Static platform, similar in appearance, with limited general health information only, without interactive components or a remote coach. D: Lifestyle advice E: Group 1 (compared to intervention group 1): medication + no lifestyle intervention F: Three group educational/social support sessions each year for 4 years after randomizations of the last volunteer G: Daily placebo pills (vs omega-3) and usual care (vs multidomain). H: Usual care I: Conventional health education in the Efficacy Study control group entailed periodic telephone calls (~3 monthly) by local research site staff to offer participants health education and advice (the intervention group did not receive such calls)

|

Duration of follow-up: Outcomes were assessed after follow-up times ranging from 12 months to 13 years. A: 2 years (for cognition) B: 2 years C: 18 months D: 18 months E: 2 years F: 10-13 years G: 36 months H: 6-8 years I: 12 months

Complete outcome data (intervention/control) A: 96% complete for MMSE B: 95% complete outcome data, no indicators of selective drop out C: 91% of participants in control, 86% in intervention D: More than half of the participants dropped out during the intervention and were not retrieved for final assessment. It seems like people were first randomised and afterwards they were asked if they were willing to participate E: Authors report no dropout from the study (at all). No attrition or excluded participants F: 74% of participants had data on the primary outcome. G: 90% complete outcome data, number of excluded did not differ significantly between groups. Excluded participants were older and with lower education. H: Follow-up data for the primary outcome of dementia were obtained for 3454 (98∙0%) participants. I: 74,7% in intervention and 70.4% in control group available for analysis.

|

Cognitive decline, incidence of dementia, incidence of cognitive impairment, activities of daily living (ADL) or quality of life. Could be cognitive screening instruments, multi-domain cognitive assessment scales, neuropsychological test batteries, quality of life instruments, ADL instruments or dementia diagnosis according to any of the validated criteria current at the time of the study.

Cognitive decline Defined as the decline in cognitive functioning measured at two separate occasions with any validated measure, including Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), composite score from a neuropsychological test battery (NTB) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

Composite score, Mean difference, IV [95%CI]: B: 0.04 [-0.02, 0.10] C: 0.02 [-0.01, 0.05] G: 0.08 [-0.03, 0.19] group 1 (multidomain plus PUFA) 0.09 [-0.00, 0.19] group 2 (multidomain plus placebo) Pooled effect random effects model: 0.03 [0.01, 0.06] favouring multi-domain. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

MMSE Mean difference, IV [95%CI]: A: 0.04 [-0.33, 0.41] group 1 (aerobic exercise plus diet) -0.05 [-0.43, 0.33] group 2 (resistance training plus diet) B: -0.03 [-0.35, 0.29] C: -0.05 [-0.19, 0.09] D: 0.32 [-0.76, 1.40] group 1 (bimonthly telephonic care) 0.14 [-0.86, 1.14] group 2 (monthly telephonic care) 0.38 [-0.66, 1.42] group 3 (bimonthly health worker-initiated visit care) 1.04 [0.00, 2.08] group 4 (bimonthly health worker-initiated visit care plus rewards) G: 0.12 [-0.15, 0.38] group 1 (multidomain plus PUFA) 0.12 [-0.15, 0.38] group 2 (multidomain plus placebo) H: 0.01 [-0.11, 0.13] Pooled effect random effects model: 0.02 [-0.06, 0.09] favouring multi-domain. Heterogeneity (I2): 0% F was not included in the MMSE meta-analysis as it used a modified version of the MMSE (3MSE, 100-point scale). F also did not observe a difference in cognitive decline measured with the 3MSE (MD 0.06 point [95%CI -0.31 to 0.44]).

MoCA Mean difference, IV [95%CI]: E: 1.10 [0.99, 1.21] group 1 (lifestyle plus medication) 0.30 [0.26, 0.34] group 2 (lifestyle only) I: 1.03 [-0.19, 2.25] Pooled effect random effects model: 0.76 [0.05, 1.46] favouring multi-domain intervention. Heterogeneity (I2): 99%

Incidence of dementia or any subtype of dementia Incidence of dementia, as assessed by an independent outcome committee. RR [95%CI]: F: 0.98 [0.61, 1.57] H: 0.93 [0.73, 1.20] Pooled effect random effects model: 0.94 [95%CI 0.76 to 1.18] favouring multi-domain Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Incidence of mild cognitive impairment, as assessed by an independent outcome committee RR (M-H, Random, 95%CI) F: 0.97 [0.76, 1.23] favouring multi-domain

Quality of life Defined by mean change on the RAND-36 (SF-36) score in intervention/control.

B: general health 1.5/-1.6, P < 0.001 physical activity -2.3/-4.0, role physical -17/-4.7, role mental -0.1/-1.7, vitality -0.3/-0.9, -0.6/-0.9, social function -0.8/-1.2, bodily pain -2.4/-2.1,

Activities of daily living (ADL) Defined as measured by any validated questionnaire, including multiple ADL related questionnaires (B), the late life function and disability instrument (C), Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Prevention Instrument (ADCSADLPI) (G), the Amsterdam Linear Disability Scale (H) and Instrumental Activities of Daily living (I). For most scales a lower score indicates more disability, but for study B the point estimate of the trial was multiplied with -1 to align the direction of the scales.

Standardized mean difference, IV [95%CI]: Effect measure: RR, RD, mean difference [95%CI]: B: 0.00 [-0.11, 0.11] C: -0.05 [-0.15, 0.05] G: 0.08 [-0.10, 0.26] group 1 (multidomain plus PUFA) 0.07 [-0.11, 0.25] group 2 (multidomain plus placebo) H: -0.01 [-0.09, 0.07] I: 0.00 [-0.12, 0.12] Pooled effect random effects model: -0.00 [-0.05, 0.04] Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

|

The authors found no convincing evidence that multi-domain interventions can prevent incident dementia, incident MCI, quality of life or activities of daily living. There was a small effect of multi-domain interventions on cognitive functioning (assessed by NTB and MoCA). Although no evidence for an effect was found when cognitive decline was assessed with the MMSE, the most widely used outcome measure. The effect assessed by NTB was only observed in studies with cognitive training, thus a potential learning effect could be present in the cognitive testing in the intervention group.

Overall, the quality of included studies was low. All studies had no blinding to allocation of participants and personnel to the (lifestyle) interventions. Moreover, Li 2018 was at high risk of selection bias due to randomization per working district. Four studies were at high risk for incomplete outcome data due to various reasons: >25% loss to follow-up (Chen 2020 and Espeland 2017), unclear randomization that may have affected drop-out (Lee 2014) and differential drop-out for MMSE in the intervention (86%) versus control (91%) (Richard 2019). High risk for selective reporting in Komulainen 2010, because the authors did not report on individual tests nor total scores for a score that they obtained. Selective reporting could not be assessed for studies that either did not publish a protocol (Lee 2014, Li 2018, Chen 2020), register in a trial register (Lee 2014, Li 2018) or only identified primary outcomes in their trial registration (Chen 2020). Finally two studies were at high risk of bias due to their statistical analysis. Li 2018 reported one-way ANOVA for two group comparison. Lee 2014 used cluster as unit of analysis instead of taking a cluster effect into account in the analysis, used single instead of multiple imputation and was unclear about the follow-up MMSE for the control group which hampered effect size interpretation.

Level of evidence: GRADE VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on dementia incidence The evidence was downgraded three levels to very low due to lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias in Espeland 2017.

VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on mild cognitive impairment. The evidence was downgraded three levels to very low quality due to indirectness since all study participants had a history of diabetes type 2, lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias in Espeland 2017 as well as the inclusion of a single study (imprecision, -1).

VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on cognitive decline measured by the composite score NTB. The evidence was downgraded three levels to very low due to lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and attrition bias in Espeland 2017 (large study with a 67.7% weight in the meta-analysis).

VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on cognitive decline measured by MMSE The evidence was downgraded three levels to very low quality due to lack of blinding to allocation of participants and indirectness since the MMSE is a screening tool that was not formally developed to quantify cognitive decline over time.

VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on cognitive decline measured by MoCA The evidence level was downgraded by three levels due to lack of blinding to allocation of participants, very serious study limitations for Li 2018, inconsistency (I2: 99%) and indirectness since the MoCA is a screening tool that was not formally developed to quantify cognitive decline over time.

VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on functioning measured by activities of daily living (ADL) The evidence was downgraded three levels to very low due to lack of blinding to allocation of participants and personnel and study limitations in two studies that collectively have a weight of 36% (attrition bias in Espeland 2017 and potential selective reporting with no published protocol (Chen 2020).

VERY LOW Multicomponent intervention vs control Effect on quality of life measured by RAND-36 (SF-36) score The evidence was downgraded three levels to very low due to lack of blinding to allocation of participants and the inclusion of a single study (imprecision, -1).

Sensitivity analyses, excluding low quality studies for:

Subgroup analysis comparing cognitive impairment versus no cognitive impairment for the cognitive decline outcome in Ngandu 2015 (MMSE >26 and <27) and Andrieu 2017 (MMSA <30 and 30). Low MMSE MD IV, random 0.06 [0.01, 0.11] High MMSE 0.01 [-0.01, 0.04] Total 0.03 [0.01, 0.05 |

|

den Brok 2022

[pooled study characteristics deduced from den Brok 2022, individual study characteristics described under Hafdi 2012 (also see row above)] |

Pooled analysis of individual participant data for cognitive functioning (measured via MMSE) from 2 parallel RCTs. These 2 RCTs were also included as study G and H in Hafdi 2021 (see row above).

G: Andrieu, 2017 (MAPT 2017) H: Moll, 2016 (preDIVA 2016)

|

Two 'prospective, randomised, open, blinded end-point' (PROBE) design studies with a community-dwelling population free from dementia at baseline over 70 years of age.

N, age G: Total: 1680 (Intervention: Group 1: 417, group 2: 420 Control: 420), mean age 75.3 yrs H: Total: 3526 (Intervention: 1890, Control: 1636), mean age 74.5 yrs

Pooled: 4162 individuals (median age 74 yrs).

G includes a high risk population with at least one of the following: spontaneous memory complaint expressed to their physician, limitation in one instrumental activity of daily living, or slow gait speed (≤ 0.8 meter/second, or more than 5 seconds to walk 4 metre).

|

See description of studies G and H in summary Hafdi 2021 (row above). |

See description of studies G and H in summary Hafdi 2021 (row above). |

Duration of follow-up: 3-4 years of follow-up

Complete outcome data (intervention/control) 3704 of 4162 individuals (89%) in MMSE analysis. |

Cognitive decline Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) mean difference 0.03 [-0.06, 0.13]. |

Planned follow-up analysis with individuals with a lower cognitive function at baseline (MMSE < 26), mean difference 0.84 (0.15-1.54).

Overall, there were some concerns for risk of bias for the two included studies in the pooled analysis.

Allocation sequence generation and concealment was definitely yes for both studies. Moll, 2016 used computer algorithm to generate randomization and used cluster randomisation with general practice as the unit of randomisation after all baseline visits at a healthcare centre were completed to conceal allocation. Andrieu, 2017 used computer generated randomisation and an automated interactive voice response system to conceal allocation.

Blinding was definitely no for both studies. Andrieu, 2017 quote “In view of the nature of the multi-domain intervention, the study was unblinded for this component, but the independent neuropsychologists who were trained to assess cognitive outcomes were blinded to group assignment”. In Moll, 2016 personnel was not blinded while participants were blinded to group allocation. Quote: "All outcome assessors were masked to group allocation and were not involved in intervention activities. The final clinical assessment was done by an independent investigator who was masked to group allocation."

Loss to follow-up was probably yes infrequent. Of the 5205 individuals in the two studies, 4162 (80%) individuals had at least one follow-up visit and were included in the pooled analysis. Excluded participants were older, with lower education, lower MMSE score and a higher mean systolic blood pressure.

Free of selective reporting is definitely yes for den Brok 2022. The pooled analysis focused on the outcomes for which both studies collected data and reported on all these outcomes.

No other biases were detected for den Brok, 2022. |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 15-10-2024

Laatst geautoriseerd : 01-10-2023

Geplande herbeoordeling : 15-10-2029

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten (www.demedischspecialist.nl/kennisinstituut) en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Samenstelling cluster

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodules is in 2021 een multidisciplinair cluster ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen en partijen (zie hiervoor de Samenstelling van het cluster) die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met dementie en delier.

Per geprioriteerde module wordt door het cluster bekeken welke expertise gewenst is bij de uitwerking en wordt gezamenlijk een verdeling gemaakt in mate van betrokkenheid van clusterleden. Alle clusterexpertiseleden die direct betrokken waren bij de modules, staan hieronder per module vermeld. Tijdens de richtlijnontwikkeling lezen alle clusterleden kritisch mee.

Clusterstuurgroep

- Dhr. prof. dr. M.G.M. (Marcel) Olde Rikkert (voorzitter), klinisch geriater, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; NVKG

- Dhr. prof. dr. A.R. (Tony) Absalom, anesthesioloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen; NVA

- Dhr. dr. J.H.J.M. (Jeroen) de Bresser, radioloog, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, Leiden; NVvR

- Mevr. J.L.M. (Josephine) Lambregts, patiëntvertegenwoordiger; Alzheimer Nederland

- Mevr. dr. I.K. (Indrag) Lampe, psychiater, OLVG, Amsterdam; NVvP

- Mevr. prof. dr. B.C. (Barbara) van Munster, internist, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen; NIV

- Dhr. prof. dr. E. (Edo) Richard, neuroloog, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; NVN

- Mevr. prof. dr. Ir. C. (Charlotte) Teunissen, klinisch chemicus, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam; NVKC

- Mevr. drs. S. (Simone) Verhaar, klinisch geriater, Catharina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven; NVKG

- Dhr. dr. A.M.J.S. (Ton) Vervest, orthopedisch chirurg, Tergooi MC, Hilversum; NOV

Betrokken clusterexpertiseleden

Richtlijn Dementie: Module 1 ‘Screening op dementie/cognitieve stoornissen in het ziekenhuis’

- Mevr. dr. T.R. (Rikje) Ruiter, internist, Maasstad Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam; NIV

- Mevr. dr. P.E. (Petra) Spies, klinisch geriater, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn/Zutphen; NVKG

Richtlijn Dementie: Module 2 ‘Preventie cognitieve achteruitgang en dementie’

- Dhr. dr. J.A.H.R. (Jurgen) Claassen, klinisch geriater, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; NVKG

- Mevr. dr. M.E.A. (Marlise) van Eersel, internist, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen; NIV

- Mevr. dr. N. (Niki) Schoonenboom, neuroloog, Spaarne Gasthuis, Haarlem/Hoofdorp, NVN

Richtlijn Dementie: Module 3 ‘Genetische risicofactoren’

- Dhr. dr. P.L.J. (Paul) Dautzenberg, klinisch geriater, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, 's-Hertogenbosch; NVKG

- Dhr. dr. E.G.B. (Jort) Vijverberg, neuroloog, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam, NVN

- Mevr. dr. M.A. (Marjolein) Wijngaarden, internist, Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum, Leiden, Leiden; NIV

Richtlijn Dementie:

Module 4 ‘Diagnostiek van dementie bij personen met een verstandelijke beperking’

- Mevr. dr. R.L. (Rozemarijn) van Bruchem-van Visser, internist, ErasmusMC, Rotterdam; NIV

- Mevr. dr. A.M. (Agnies) van Eeghen, arts Verstandelijk Gehandicapten, AmsterdamUMC, Amsterdam en ’s Heeren Loo; NVAVG

- Dhr. dr. R.B. (Rients) Huitema, klinisch neuropsycholoog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen, Groningen; NIP

- Mevr. dr. M. (Marieke) Perry, huisarts/onderzoeker, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; NHG

- Mevr. drs. M.M.E. (Marlies) Sleegers-Kerkenaar, klinisch geriater, Catharina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven; NVKG

- Mevr. drs. V.C.J. (Vera) van Stek-Smits, klinisch neuropsycholoog, Basalt Revalidatie HMC Westeinde, Den Haag; NIP

Richtlijn Delier bij volwassenen en ouderen:

Module 5 ‘Preventief staken van middelen met anticholinerge werking bij risico delier’

- Mevr. drs. L. (Lieke) Mitrov, ziekenhuisapotheker, Maasstad Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam; NVZA

- Dhr. dr. J.A.H.R. (Jurgen) Claassen, klinisch geriater, Radboudumc, Nijmegen; NVKG

- Dhr. dr. P.L.J. (Paul) Dautzenberg, klinisch geriater, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, 's-Hertogenbosch; NVKG

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle clusterleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van de clusterleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

Clusterstuurgroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Olde Rikkert* |

Hoogleraar Geriatrie, Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Hoofdredacteur Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde |

Geen; uitsluitend ZonMw gefinancierd onderzoek dat overheidsbelang centraal stelt. Sinds 2017 geen farma-onderzoek meer. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Absalom |

Hoogleraar Anesthesiologie, UMCG, Groningen |

Consultancy werkzaamheden (betaald, alle betalingen aan UMCG) 6. Consultancy werk voor Becton Dickinson (Eysins, Switzerland) en Terumo (Tokyo, Japan) – technische advies over spuitpompen. Niet gerelateerd aan dementie/ MCI/ delier. |

Extern gefinancierd onderzoeken, maar financier heeft geen belangen bij de richtlijn. * Rigel Pharmaceuticals (San Francisco, USA) (PAST) * The Medicines Company (Parsippany, NJ, USA)(PAST) |

Geen restricties, omdat adviseurswerk niet gerelateerd is aan de afbakening van het cluster |

|

Bresser |

- Neuroradioloog 1.0fte, LUMC, Leiden |

Geen |

Mijn onderzoek wordt mede gesponsord door Alzheimer Nederland. Deze financier heeft geen belang bij bepaalde uitkomsten van de richtlijn. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Lambregts |

Medewerker belangenbehartiging bij Alzheimer Nederland |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Lampe |

Psychiater, OLVG Ziekenhuis, Amsterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Richard |

Neuroloog (1.0fte) Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

- Neuroloog-onderzoeker AmsterdamUMC, locatie AMC, gastvrijheidsaanstelling. |

Geen, uitsluitend onderzoek financiering van non-profit instellingen (e.g. ZonMw, Europese Commissie). |

Geen restrictie |

|

Teunissen |

Hoofd Neurochemisch laboratorium, Afdeling Klinische Chemie, AmsterdamUMC, lokatie VUmc, Amsterdam |

*Adviseur voor educatief blad: Mednet Neurologie (betaald). * Alle betalingen zijn aan het AmsterdamUMC. |

Onderzoeksubsidies zijn ontvangen van European Commission (Marie Curie International Training Network, JPND), Health Holland, ZonMW, Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, The Selfridges Group Foundation, Alzheimer Netherlands, Alzheimer Association. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Munster |

* Hoogleraar Interne Geneeskunde, Ouderengeneeskunde/Geriatrie, UMCG, Groningen. *Plaatsvervangend opleider Geriatrie, UMCG, Groningen. |

- 2020 – heden Voorzitter Alzheimer Centrum Groningen (alle functies zijn onbetaald) |

*2022 ZONMw: Young Onset Dementia- INCLUDED: Advance care planning. 2022 ZEGG/ZONMw: "The impact of a comprehensive geriatric assessment including advance care planning in acutely hospitalized frail patients with cognitive disorders: the GOAL study" |

Geen restrictie |

|

Verhaar |

Klinisch geriater, Catharina Ziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Lid richtlijnen commissie NVKG (onbetaald) |

Onderzoeksubsidies zijn ontvangen van European Commission (Marie Curie International Training Network, JPND), Health Holland, ZonMW, Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, The Selfridges Group Foundation, Alzheimer Netherlands, Alzheimer Association. |

Geen restrictie |

|

Vervest |

Orthopedisch chirurg, Tergooi MC, Hilversum |

Lid regionaal tuchtcollege van de gezondheidszorg Den Haag |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

Clusterexpertisegroep

|

Clusterlid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Appelman |

Neuroradioloog, Universitair Medisch Centrum Groningen |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restricties |

|

Berckel |

Nucleair geneeskundige Amsterdam UMC |

Alleen betaling aan instituut. Geen directe betaling. |

*Onderzoeksprojecten van Bart van Berckel ontvingen subsidie van EU-FP7, CTMM, ZonMw, NWO en Alzheimer Nederland. BvB heeft contract research uitgevoerd voor Rodin, IONIS, AVID, Eli Lilly, UCB, DIAN-TUI en Janssen. * Bart van Berckel was spreker bij een symposium georganiseerd door Springer Healthcare. *Bart van Berckel verricht consultancy activiteiten voor IXICO in de vorm van beoordeling van PET scans. BvB is een trainer voor GE. * Bart van Berckel ontvangt alleen van Amsterdam UMC financiële tegemoetkoming." |

Geen restricties |

|

Claassen |

Universitair hoofddocent en klinisch geriater (1.0 fte), Radboudumc, Nijmegen |

Geen |

*Fase 3 onderzoek Novo Nordisk (EVOKE, NCT04777396. Wereldwijde geneesmiddelenstudie (semaglutide) over Alzheimer. Rol als lokale PI. Middel komt niet aan bod in huidige vijf modules. *MOCIA-project, gefinancierd door ZonMW (www.mocia.nl). *ABOARD onderzoek (gefinancierd door ZonMW en Health Holland, projectnummer: 73305095007) *Onderzoekslijn rond de rol van vasculaire factoren in het ontstaan van en progressie van dementie co-auteur van het boek ‘Wat kun je doen aan dementie? ‘ uitg Lannoo Campus" |

Geen restricties, belangen zijn niet gerelateerd aan de uit te werken module |

|

Dautzenberg |

*Klinisch geriater (0.8fte), Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, 's-Hertogenbosch |

* Betaald klinisch geriater JBZ, Staflid vakgroep geriatrie JBZ met supervisie taken kliniek, poli kliniek en SEH; consulentschap bij Reinier van Arkel; polikliniek geriatrie. Lid Top Klinisch Centrum Cognitie. |

Geen |

Geen restricties, belangen zijn niet gerelateerd aan de uit te werken modules |

|

Groeneveld |

Verpleegkundig consulent geriatrie, Catharina ziekenhuis, Eindhoven |

EBPscholing en borging in Catharinaziekenhuis (2 uur per week vanuit KIPZ) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Lahdidioui |

Internist ouderengeneeskunde, HagaZiekenhuis, Den Haag. |

* Docent, SOOL Leiden (Specialisme Ouderengeneeskunde Opleiding Leiden), Leids Universitair Medisch Centrum; (betaald). |

* ZonMw - Stimuleren van weloverwogen besluitvorming aangaande deelname aan het bevolkingsonderzoek baarmoederhalskanker bij Turks- en Marokkaans-Nederlandse vrouwen – a blended learning approach - projectleider |

Geen restrictie |

|

Lavalaye |

Nucleair geneeskundige, Sint Antonius ziekenhuis |

Raad van advies prostaatkankerstichting (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Huitema |

Klinisch neuropsycholoog, UMCG, Groningen. |

Geen |

* A Functional Architecture of the Brain for Vision (ERC grant number 339374) - localPI * Young Onset Dementia- INCLUDED (ZonMw) |

Geen restrictie |

|

Mitrov |

Ziekenhuisapotheker, Maasstad ziekenhuis en Ikazia Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Perry |

* Huisarts, Huisartsenpraktijk Velp, 0.5 fte |

* Auteur hoofdstuk Vergeetachtigheid in Álledaagse klachten 2020 (onkostenvergoeding) * Diverse malen gastspreker bij verschillende Alzheimer Cafés (vrijwillig) |

Projectleider DementieNet (financiering door Giekes-Strijbis fonds, Alzheimer Nederland en ZonMw) |

Geen restrictie |

|

Roks |

Neuroloog, ETZ Tilburg |

METC Brabant, lid en vice voorzitter (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Ruiter |

*Internist ouderen geneeskunde en klinische farmacologie (0.8fte), Maasstad Ziekenhuis, Rotterdam *Post-doctoraal onderzoeker & Epidemioloog B (0.1fte), Erasmus MC, Rotterdam |

Voorzitter werkgroep kwaliteit & richtlijnen kerngroep ouderengeneeskunde NIV |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Schoonenboom |

Neuroloog, Spaarnegasthuis, Haarlem |

NVN werkroep cognitieve neurologie Principal investigator Spaarne Gasthuis (Maria Stichting) PRECODE advies wetensc NGN wetenschapscommissie |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Seelaar |

*Neuroloog, Erasmus MC, afdeling neurologie & Alzheimercentrum Erasmus MC (0.4fte) |

Member of the working group European Reference Network of rare neurological diseases (ERN-RND) working group Frontotemporal dementia. Dit betreft advies mbt Europese richtlijnen en advies ikh diagnostiek en zorg mbt Forntotemporale dementie (onbetaald) |

*A phase 2 study to evaluate safety of long-term AL001 Dosing in FTD patients (INFRONTS-2). Company: Alector, Clinicaltrails.gov, NCT03987295. Trial bij patienten met FTD obv een Progranuline mutatie. Geen belangenconflict bij (bepaalde) uitkomst van het advies of de richtlijn" |

Geen restrictie |

|

Simons |

Internist-intensivist, Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, 's Hertogenbosch |

FCCS Instructeur NVIC (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Sleegers-Kerkenaar |

Klinisch geriater, Catharina Ziekenhuis Eindhoven |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Spies |

Klinisch geriater, Gelre ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn & Zutphen |

*Redactie leerboek Inleiding in de gerontologie en geriatrie (betaald) |

Mede-auteur van het boek 'Wat kun je doen aan dementie?' (betaald) |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Bruchem-Visser |

Internist ouderengeneeskunde, Erasmus MC, 1 fte |

Medezeggenschapsraad CSG Comenius (onkostenvergoeding) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Van Eeghen |

Arts voor Verstandelijk Gehandicapten. Werkgevers: *Emma Kinderziekenhuis, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam; *Advisium, 's Heeren Loo, Amersfoort |

Scientific advisory boards bij: * Jazz pharmaceuticals, op gebied van studies over effectiviteit van cannabis-olie bij genetische syndromen. * Shionogu pharmaceuticals: op gebied van Fragiele X syndroom

Overige nevenfuncties: * Voorzitter wetenschappelijke adviesraad Stichting TSC Fonds * Wetenschappelijke adviesraad Zeldsamen * Voorzitter richtlijn medische begeleiding bij Down Syndroom * Voorzitter Stuurgroep Richtlijnontwikkeling NVAVG * Voorzitter werkgroep richtlijnontwikkeling ERN ITHACA |

PI van diverse internationale richtlijnprojecten, funded door Europese Commissie / European Reference Network ITHACA

Onderzoekslijn dementie bij genetische syndromen en/of VB, funding door Epilepsie NL, ’s Heeren Loo.

Onderzoekslijn cannabidiol studies funded door Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Onderzoekslijnen naar uitkomstmaten funded door ForWishdom, APH Amsterdam UMC, ’s Heeren Loo. Overige onderzoeksprojecten funded door Metakids, ’s Heeren Loo, ZonMw.

|

Geen restrictie |

|

van Eersel |

Internist-ouderengeneeskunde, UMCG, Groningen |

Lid van Wetenschapscommissie Ouderengeneeskunde NIV/NVKG (onbetaald)

|

ZonMW (#73305095007) - ABOARD, A Personalized Medicine Approach for Alzheimer’s Disease. |

Geen restrictie |

|

van Stek-Smits |

Neuropsycholoog/gezondheidszorgpsycholoog, Basalt Revalidatie, locatie HMC Westeinde, Den Haag (poliklinische neuro-revalidatie) |

* Bestuurslid Nederlands Geheugenpoli Netwerk |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Vernooij |

*Hoogleraar/medisch specialist, afd Radiologie Erasmus MC 0.8fte *Hoogleraar, afd Epidemiologie, Erasmus MC 0.2fte |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Vijverberg |

*Neuroloog, Amsterdam UMC afdeling Neurologie/ Alzheimercentrum Amsterdam |

Consultant/adviseurschap is voor meerdere bedrijven die onderzoek doen naar medicatie bij AD/FTD/PSP. Geen invloed op de huidige richtlijn |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

|

Wijngaarden |

Internist-ouderengeneeskunde (0.8fte), LUMC, Leiden |

* lid werkgroep NIV ouderengeneeskunde kwaliteit en richtlijnen (onbetaald) * lid richtlijn dementie in de palliatieve fase (onbetaald) |

Geen |

Geen restrictie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door de afvaardiging van Alzheimer Nederland in de clusterstuurgroep. De verkregen input is actief meegenomen bij het opstellen van de uitgangsvragen, de keuze voor de uitkomstmaten en bij het opstellen van de overwegingen. De conceptmodule is tevens ter commentaar voorgelegd aan Alzheimer Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijnmodule is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling is de richtlijnmodule op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module 1 ‘Screening op dementie/ cognitieve stoornissen in het ziekenhuis’ |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet, het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, of het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 2 ‘Preventie cognitieve achteruitgang en dementie’ |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet, het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, of het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 3 ‘Genetische risicofactoren’ |

Geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (>40.000 patiënten), volgt uit de toetsing dat het overgrote deel (±90%) van de zorgaanbieders en zorgverleners al aan de norm voldoet, het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft, of het geen toename in het aantal in te zetten voltijdsequivalenten aan zorgverleners betreft en het geen wijziging in het opleidingsniveau van zorgpersoneel betreft. Er worden daarom geen financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module 4 ‘Diagnostiek van dementie bij personen met een verstandelijke beperking’ |

Geen financiële gevolgen |