TRAM/DIEP flap types breast reconstruction

Question

What is the role of a free TRAM flap, pedicled TRAM flap or DIEP flap?

Recommendation

A free (muscle sparing) TRAM or DIEP flap is preferable to a pedicled TRAM flap.

In patients with sufficient abdominal tissue, perform a DIEP flap or free (muscle sparing) TRAM flap.

Refer patients without a suitable abdominal donor site who have a strong preference for autologous reconstruction to a centre with specialized microsurgical expertise.

Considerations

Autologous breast reconstructions, such as a pedicled or free vascularized tissue flap, use the body’s own tissue. Major improvements in breast reconstruction over the past thirty years have been the introduction of the pedicled TRAM flap in the 1980s and the implementation of microsurgical techniques. The pedicled TRAM flap allowed better shaping of the breast. Microsurgical techniques subsequently improved the perfusion of the flaps used. Other important developments included the reduction in donor site morbidity and skin sparing mastectomy techniques, resulting in a more predictable aesthetic result.

Assessment of indication and use of current autologous breast reconstructions techniques faces the same challenges as almost every surgical treatment, namely the lack of randomized studies. We performed a number of meta-analyses in an attempt to combine the results of multiple studies in order to create a comparison. Interpretation of these data is complicated by the heterogeneity of the results, limiting the value of the conclusions of these meta-analyses. The recommendations about the autologous reconstruction technique to be used outlined below are therefore primarily based on publications from centers with extensive expertise in the field of one or two techniques. The final choice is primarily dictated by patient characteristics, such as breast size, amount of available abdominal tissue, and the technical expertise of the surgical team, including mastery of microsurgical techniques. The advantages and disadvantages of each technique affecting selection are briefly summarized below.

Pedicled Transverse Rectus Abdominis Myocutaneous (TRAM) flap

Hartrampf et al described the pedicled TRAM flap in 1982, consisting of skin, fat and muscle tissue harvested from the lower abdomen. This represented a major leap forward in breast reconstruction, as a conical breast shape could now be achieved without using an implant. The procedure is not complex, and microsurgical techniques are not required. One problem with the pedicled TRAM flap is the risk of partial flap necrosis or venous congestion. This is primarily caused by the blood supply, which comes from the non-dominant superior epigastric vessels. Additionally, a polypropylene mesh is often required to strengthen the abdominal wall, as either one or both rectus abdominis muscles are transposed. This also leads to a relatively elevated risk of problems with venous congestion of the flap and requires strict selection (including a BMI <30 kg/m, no smoking, no diabetes mellitus).

Free TRAM flap

The free TRAM flap is the most commonly used free vascularized flap in breast reconstructions worldwide. The free TRAM flap improves the options for shaping the breast, as its transposition is not limited by the vascular pedicle. Additionally, the free TRAM flap theoretically has a better blood supply than the pedicled TRAM flap as the dominant inferior epigastric vessels are used as the pedicle (Vega et al, 2008). However, microsurgical expertise is required, and removal of one or both rectus abdominis muscles requires use of a polypropylene mesh to strengthen the abdominal wall.

The muscle-sparing TRAM flap (mini-TRAM)

In this procedure, only a small part of the rectus muscle is harvested; usually a section overlapping the medial and/or lateral row of perforating vessels. The muscle-sparing TRAM flap is a modification of the TRAM flap designed to reduce donor site morbidity. This flap can be used both pedicled and free. Use of a mesh to strengthen the abdominal wall is usually unnecessary (Nahabedian & Manson, 2002).

Free Deep Inferior Epigastric artery Perforator (DIEP) flap

The perforator flap concept, in which the feeding vessels between the muscles are dissected out, was applied to the TRAM flap resulting in the DIEP flap (Koshima & Soeda, 1989). This causes less harm to the donor site, as the rectus abdominis muscles and nerves are spared. Strengthening of the abdominal wall using a mesh is not required. However, the surgery is much more technically demanding, with longer operative times than a TRAM flap.

Free Superficial Inferior Epigastric Artery (SIEA) flap

This is a non-perforator flap from the lower abdomen (Chevary, 2004) with a further reduction of donor site complications (compared to the DIEP flap), as no dissection between rectus muscles is required. The blood supply to the flap is provided by the superficial inferior epigastric vessels that originate from the femoral arteries in the groin. These arteries are only sufficiently large in about 24% of cases (Rozen et al, 2010).

However, the risk of microsurgical complications is higher due to small blood vessel diameters of sometimes less than 1.5 mm, a short vascular pedicle with a smaller perfusion area, and the risk of lymph leakage in the groin (Spiegel & Khan, 2007). The SIEA flap is only occasionally used in The Netherlands.

Not all women have sufficient abdominal excess tissue for a unilateral or bilateral breast reconstruction. Therefore, autologous breast reconstruction techniques that use other body sites with skin/fat excess were developed. The most commonly used techniques are described below.

Free Superior or Inferior Gluteal Artery Perforator (SGAP/IGAP) flap

This perforator flap from the gluteal region spares the gluteus muscles and is primarily used if the abdominal area is not suitable as a donor site (LoTempio & Allen, 2010). The procedure is technically challenging. The vascular pedicle is relatively short, the patient is in a prone or lateral supine position, and there is a significant risk of contour deformation of the buttock along with pain complaints when sitting following an IGAP. The risk of microsurgical complications is also higher than for a DIEP or TRAM flap (Baumeister et al, 2010; Mirzabeigi et al, 2011).

Transverse Myocutaneous Gracilis (TMG) flap

This flap can be used for the reconstruction of smaller breasts. It is a skin/muscle flap in which skin, fat and the gracilis muscle are harvested from the inner thigh. The flap is relatively simple to harvest, with relatively few functional complaints following surgery. The skin island can also be extended vertically to obtain more skin, fat and volume (Wechselberger & Schoeller, 2004).

However, the volume of the flap is not particularly large, and the skin island is relatively small. This makes the flap less suitable for delayed breast reconstructions and often results in a relatively small breast. Additionally, secondary contour deformities of the breast may occur due to atrophy of the gracilis muscle (Locke et al, 2012).

Microsurgeons are continuously searching for the ideal alternative flap when the abdomen is not a suitable donor site. However, these flaps – such as the Rubens flap, the Profunda Artery Perforator (PAP) flap or the lateral thigh perforator (LTP) flap – are currently only very rarely used, and therefore not discussed in further detail here. Referral to a center with specific expertise is recommended for these procedures.

Evidence

Background

The following autologous tissue reconstructions are currently being performed in The Netherlands (see considerations paragraph for autologous breast reconstruction technique details): pedicled TRAM flap, pedicled latissimus dorsi flap, free TRAM, DIEP, SIEA, SGAP, IGAP and TMG flaps. Rarely used flaps are the Rubens fat pad flap and more recently the PAP flap and the lateral thigh perforator flap. The choice depends on patient wishes, plastic surgeon experience and preference, and access to information. Regarding the latter two, reducing variation between practices is desirable. This chapter also summarizes the current literature on this topic.

Conclusions / Summary of Findings

1. What are the (un)favorable effects of a free TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

|

very low (GRADE) |

Flap necrosis

The risk of flap necrosis appears to decrease by factor 2 if the breast is reconstructed using a free TRAM flap rather than a DIEP flap. Sources (Man et al, 2009; Nelson et al, 2010; Takeishi et al, 2008) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Partial flap necrosis

There is a trend toward the risk of partial flap necrosis reducing by about two-thirds if a breast is reconstructed using a free TRAM flap rather than a DIEP flap. Sources (Man et al, 2009; Nelson et al, 2010) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Fat necrosis

The risk of fat necrosis appears to decrease by almost a factor of 2 if a breast is reconstructed using a free TRAM flap rather than a DIEP flap.

Sources (Man et al, 2009; Nelson et al, 2010; Takeishi et al, 2008) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Abdominal weakness and bulge

The risk of abdominal weakness and bulge appears to increase by almost a factor of 2 if a breast is reconstructed using a free TRAM flap rather than a DIEP flap.

Sources (Man et al, 2009; Nelson et al, 2010; Takeishi et al, 2008) |

2. What are the (un)favorable effects of a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a TRAM flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

|

very low (GRADE) |

Flap necrosis

There appears to be no difference in flap necrosis between breast reconstructions with pedicled or free TRAM flaps.

Sources (Baldwin et al, 1994; Gherardini et al, 1994; Moran et al, 2000) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Partial flap necrosis

There appears to be no difference in partial necrosis between breast reconstructions with pedicled or free TRAM flaps.

Sources (Baldwin et al, 1994; Gherardini et al, 1994; Moran et al, 2000) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Fat necrosis

There appears to be no difference in fat necrosis between breast reconstructions with pedicled or free TRAM flaps.

Sources (Baldwin et al, 1994; Moran et al, 2000) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Abdominal weakness and bulge

The risk of abdominal weakness and bulge may be over twice as low if the breast is reconstructed using a pedicled rather than a free TRAM flap.

Sources (Moran et al, 2000) |

|

- |

Pulmonary embolism, aesthetic result and oncologic safety There is a lack of evidence for the effect of breast reconstruction using a DIEP flap compared with a free TRAM flap on pulmonary embolism, aesthetic result and oncologic safety. |

3. What are the (un)favorable effects of a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

|

very low (GRADE) |

Flap necrosis

The risk of flap necrosis may be lower if the breast is reconstructed using a pedicled TRAM flap rather than a free DIEP flap.

Sources (Chun et al, 2010) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Fat necrosis

The risk of fat necrosis appears to decrease by factor 2 if the breast is reconstructed with a pedicled TRAM flap rather than a DIEP flap.

Sources (Chun et al, 2010) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Abdominal weakness and bulge

The risk of abdominal weakness and bulge may be lower if the breast is reconstructed using a pedicled TRAM flap rather than a free DIEP flap.

Sources (Chun et al, 2010) |

|

very low (GRADE) |

Abdominal hernia

The risk of abdominal hernia may be higher if the breast is reconstructed using a pedicled TRAM flap rather than a free DIEP flap.

Sources (Chun et al, 2010) |

|

- |

Partial necrosis, pulmonary embolism, aesthetic result and oncologic safety. There is a lack of evidence for the effect of breast reconstruction using a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap on partial necrosis, pulmonary embolism, aesthetic result and oncologic safety. |

Literature summary

1. What are the (un)favorable effects of a free TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

One systematic review (Man et al, 2009) of six comparative retrospective sequential patient series (Bajaj et al, 2006; Blondeel et al, 1997; Bonde et al, 2006; Kroll et al, 2000; Nahabedian et al, 2005; Scheer et al, 2006) and two more recently published comparative retrospective patient series (Nelson et al, 2010; Takeishi et al, 2008) were included in the literature analysis.

A total of eight retrospective patient series examined the complications of a free TRAM flap reconstruction with those of a DIEP flap reconstruction in patients with immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.

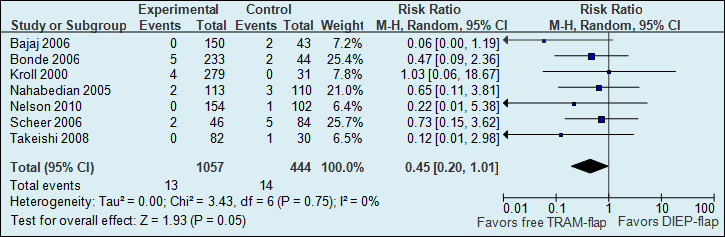

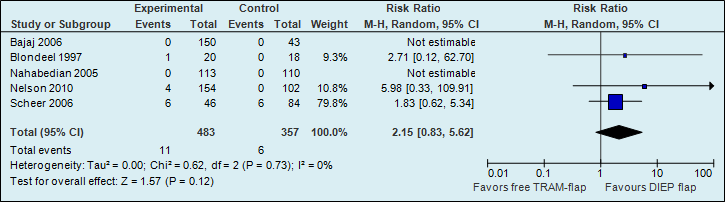

A meta-analysis of seven studies showed that the probability of total flap necrosis is two times higher if reconstructions are performed using a DIEP flap (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Total flap loss (major postoperative flap complication)

The number of total flap necrosis in the studies decreased from 32 per 1000 to 12 per 1000.

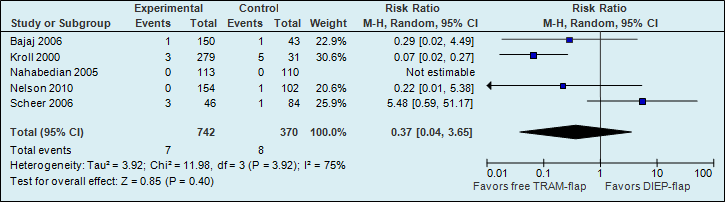

A meta-analysis of five studies showed that the risk of partial flap necrosis is higher if reconstructions are performed with a DIEP flap; however, this difference is not statistically significant (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Partial flap necrosis (major postoperative flap complication)

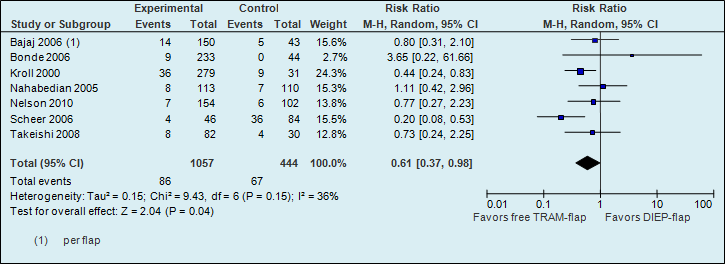

A meta-analysis of seven studies showed that the risk of fat necrosis is almost two times higher if reconstructions are performed using a DIEP flap (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Fat necrosis (postoperative flap complication)

The number of fat necrosis in the studies decreased from 151 per 1000 to 92 per 1000.

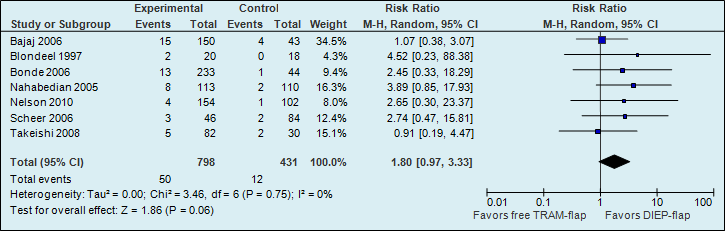

A meta-analysis of seven studies showed that the risk of abdominal weakness and bulge is almost two times higher if reconstructions are performed using a free TRAM flap (see figure 4).

Figure 4. Abdominal bulge (postoperative donor site complication)

The number of abdominal weakness and bulge cases in the studies decreased from 28 per 1000 to 50 per 1000.

A meta-analysis of five studies showed that the risk of abdominal hernia is more than twice as high if reconstructions are performed with a free TRAM flap (see figure 5).

Figure 5. Abdominal bulge (postoperative donor site complication)

Oncologic safety and aesthetic result were not studied as outcome measures.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measures flap necrosis, fat necrosis, abdominal weakness and bulge is very low, as the studies were not randomized (highly significant limitations in study design) and the number of events is low (imprecision).

The level of evidence for the outcome measure partial flap necrosis is very low, as the studies were not randomized (highly significant limitations in study design) and the results were conflicting (heterogeneity; I2 = 75%).

Furthermore, the studies were performed in ‘centers of excellence’, so the question remains whether their results can be extrapolated to all other centers.

The level of evidence for the outcome measures pulmonary embolism, oncologic safety and aesthetic result cannot be assessed, as there are no comparative studies with these outcome measures.

2. What are the (un)favorable effects of a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a TRAM flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

Three comparative retrospective cohorts (Baldwin et al, 1994; Gherardini et al, 1994; Moran et al, 2000) were included in the systematic literature review. These studies compared the number of complications of a pedicled TRAM flap with those of a free TRAM flap in patients undergoing immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.

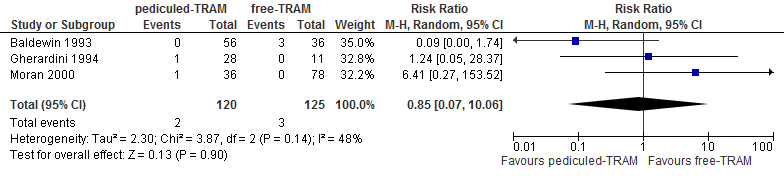

A meta-analysis of three studies showed no differences in flap necrosis between reconstructions using a pedicled or free TRAM flap (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Total flap loss

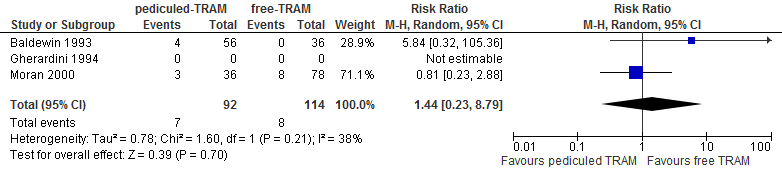

A meta-analysis of three studies showed that the risk of partial flap necrosis is twice as high if reconstruction is performed with a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a free TRAM flap (not statistically significant, see figure 7).

Figure 7. Partial flap loss

A meta-analysis of two studies showed no differences in fat necrosis between reconstructions using a pedicled or free TRAM flap (see figure 8).

Figure 8. Fat necrosis

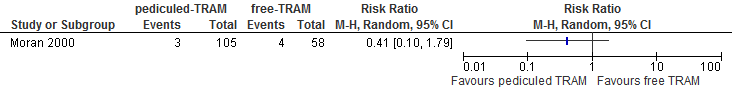

A systematic review of one study showed that the chance of abdominal weakness and bulge is higher in reconstructions with a free TRAM flap compared with a pedicled TRAM flap (not statistically significant, see figure 9).

Figure 9. Abdominal bulge or hernia

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measures of flap necrosis, partial flap necrosis and fat necrosis is very low, because the studies were not randomized (highly significant limitations in study design) the study populations are small, the number of events is low (imprecision) and the results are conflicting (statistical heterogeneity with an I2 varying from 38% to 71%).

The level of evidence for the outcome measures abdominal weakness and bulge is very low, as the studies were not randomized (highly significant limitations in study design) with a small study population and a low number of events (imprecision).

Furthermore, the studies were performed in ‘centers of excellence’, so the question remains whether their results can be extrapolated to all other centers.

The level of evidence for the outcome measures pulmonary embolism, oncologic safety and aesthetic result cannot be assessed, as there are no comparative studies with these outcome measures.

3. What are the (un)favorable effects of a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

One retrospective cohort study (Chun et al, 2010) was included in the systematic literature review. Chun et al compared the number of complications of a pedicled TRAM flap with those of a DIEP flap in patients undergoing immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.

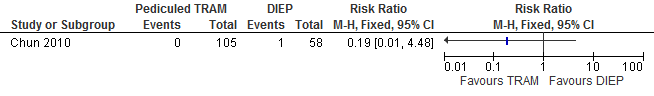

The results show that the risk of flap necrosis is higher if reconstructions are performed with a DIEP flap compared with a pedicled TRAM flap (not statistically significant, see figure 10).

Figure 10. Total flap loss

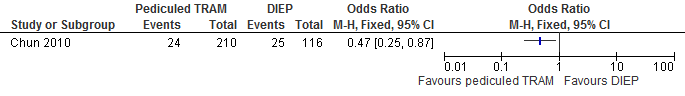

The results show that the risk of fat necrosis is significantly higher if reconstructions are performed with a DIEP flap compared with a pedicled TRAM flap (see figure 11).

Figure 11. Fat necrosis

The number of fat necroses in the studies decreases from 216 per 1000 to 101 per 1000.

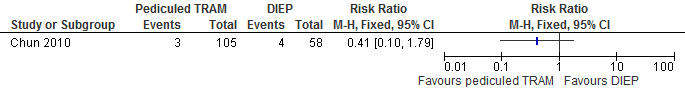

The results show that the risk of abdominal weakness and bulge is higher if reconstructions are performed with a DIEP flap compared with a pedicled TRAM flap (not statistically significant, see figure 12).

Figure 12. Abdominal bulge

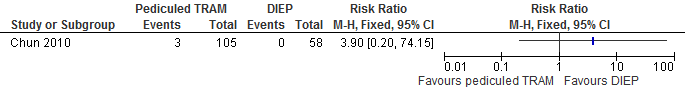

The results show that the risk of abdominal hernia is higher if reconstructions are performed with a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap (not statistically significant, see figure 13).

Figure 13. Hernia

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence for the outcome measures flap necrosis, fat necrosis, abdominal weakness and bulge/hernia is very low, as the studies were not randomized (highly significant limitations in study design), the study populations are small and the number of events is low (imprecision).

Furthermore, the studies were performed in ‘centers of excellence’, so the question remains whether their results can be extrapolated to all other centers.

The level of evidence for the outcome measures partial necrosis, pulmonary embolism, oncologic safety and aesthetic result cannot be assessed, as there are no comparative studies with these outcome measures.

Search and select

Three systematic literature analyses were performed in order to answer the primary question, examining the following questions:

- What are the (un)favorable effects of a free TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

- What are the (un)favorable effects of a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a free TRAM flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

- What are the (un)favorable effects of a pedicled TRAM flap compared with a DIEP flap in patients with an indication for autologous breast reconstruction?

Search and selection (Method)

Medline (OVID), Embase and Cochrane databases were searched for autologous breast reconstruction. The search justification is listed at the end of this chapter. The literature search yielded 751 results. Studies that met the following selection criteria were included in the literature summary: original studies; comparative studies; systematic review of comparative studies; comparison of different autologous breast reconstruction techniques and complications, aesthetic result and oncologic safety as outcome measures.

Relevant outcome measures

The working group considered major complications (total flap necrosis; partial flap necrosis; pulmonary embolism) a critical outcome measure for decision-making, and aesthetic result, oncologic safety and minor complications (fat necrosis; abdominal weakness and bulge, abdominal herniation) important outcome measures for decision-making.

Seven studies were included in the literature analysis (Baldwin et al, 1994; Chun et al, 2010; Gherardini et al, 1994; Man et al, 2009; Moran et al, 2000; Nelson et al, 2010; Takeishi et al, 2008), including one systematic review (Man et al, 2009).

Methods

Authorization date and validity

Last review : 01-03-2015

The Board of the Dutch Society for Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (NVPC) will assess whether this guideline is still up-to-date in 2018 at the latest. If necessary, a new working group will be appointed to revise the guideline. The guideline’s validity may lapse earlier if new developments demand revision at an earlier date.

As the holder of this guideline, the NVPC is chiefly responsible for keeping the guideline up to date. Other scientific organizations participating in the guideline or users of the guideline share the responsibility to inform the chiefly responsible party about relevant developments within their fields.

General details

Guideline development was funded by the Quality Fund for Medical Specialists (SKMS) and The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw).

Scope and target group

Guideline goal

To develop a multidisciplinary, evidence-based guideline for breast reconstruction in women undergoing breast conserving therapy or mastectomy for breast cancer, or following prophylactic mastectomy.

Guideline scope

The guideline focuses on all patients with an indication for breast reconstruction following breast conserving therapy or mastectomy. Additionally, the guideline may be applied to breast reconstruction in patients who have undergone surgical treatment for a benign breast condition. The guideline does not comment on the treatment of breast cancer. We refer the reader to the NABON guideline for the treatment of breast cancer (www.richtlijnendatabase.nl), which this guideline complements.

Unfortunately, circumstances did not permit a medical oncologist representing the NVMO to participate in the working group. Thus, the current version lacks a module on chemotherapy and breast reconstruction. The working group strives to create such a module for this guideline in the near future.

Intended audience for the guideline

The guideline aims to provide practical guidance for plastic surgeons and members of the multidisciplinary breast cancer team (surgical oncologist, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, radiologist, pathologist, psychologist, breast care nurse specialist). A version for patients has recently been developed (https://www.b-bewust.nl/pif_borstreconstructie).

Samenstelling werkgroep

A multidisciplinary working group was appointed to develop the guideline in October 2011, consisting of representatives from all relevant specialties involved in the care for patients with breast reconstruction (see above for working group membership). Working group members were mandated by their professional organizations. The working group worked on developing the guideline for 2 years. The working group is responsible for the full text of this guideline.

- Dr. M.A.M. Mureau (President), MD, PhD, plastic surgeon, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam

- Professor Dr. R.R.W.J. van der Hulst, MD, PhD, plastic surgeon, Maastricht University Medical Center/Orbis Medical Center/Viecuri Medical Center, Maastricht

- Dr. L. A.E. Woerdeman, MD, PhD, plastic surgeon, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek / Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam

- Drs. A.A.W.M van Turnhout, MD, plastic surgeon, Tergooi Hospital, Hilversum Site

- N.A.S. Posch, MD, plastic surgeon, Haga Hospital, The Hague

- Dr. M.B.E. Menke-Pluijmers, MD, PhD, oncologic surgeon, Albert Schweitzer Hospital, Dordrecht

- Dr. E.J.T. Luiten, MD, PhD, oncologic surgeon, Amphia Hospital, Breda

- Drs. A.H. Westenberg, MD, radiotherapist/oncologist, Arnhem Radiotherapy Institute, Arnhem

- Dr. J.P. Gopie, PhD, psychologist, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden

- Dr. H.M. Zonderland, MD, PhD, radiologist, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam

- Drs. M. Westerhof, MSc, Netherlands Breast Cancer Association, Utrecht

- E.M.M. Krol-Warmerdam MA, V&VN Nurse Specialists, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden

With support from

- Drs. B.S. Niël-Weise, MD, microbiologist / epidemiologist, senior advisor, Knowledge Institute for Medical Specialists

Declaration of interest

Working group members declared any (financial) ties with commercial companies, organizations or institutions involved in the field covered by the guideline for the past five years in writing. An overview is available on request from the office of the Knowledge Institute for Medical Specialists (KIMS).

Patient involvement

Patients are represented by a delegate from the Netherlands Breast Cancer Association in this guideline.

Method of development

Implementation

Guideline implementation and practical applicability of the recommendations was taken into consideration during various stages of guideline development. Factors that may promote or hinder implementation of the guideline in daily practice were given specific attention.

The guideline is distributed digitally among all relevant professional groups. The guideline can also be downloaded from the Dutch Society for Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery website: www.nvpc.nl, the guideline website: www.richtlijnendatabase.nl and the Quality Organization for Medical Specialists.

Methods and proces

AGREE

The guideline has been drafted in accordance with the requirements outlined in the ‘Guidelines 2.0’ report of the Guideline Advisory Committee of the Council on Science, Education and Quality (WOK). This report is based on the AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II) (www.agreecollaboration.org), an instrument designed to assess the quality of guidelines with broad international support.

Primary questions and outcome measures

Based on the outcomes of the bottleneck analysis, the president and advisor formulated draft primary questions. These were discussed and defined together with the working group. Subsequently, the working group determined which outcome measures were relevant for the patient for each primary question, examining both desired and undesirable effects. The working group valuated these outcomes based on their relative importance as crucial, important and unimportant.

Literature search and selection strategy

Specific search terms were used to identify published scientific studies related to each individual primary question in Medline, Cochrane and, where necessary, Embase. Additionally, the references of the selected articles were screened for additional relevant studies. Studies offering the highest level of evidence were sought out first. Working group members selected articles identified by the search based on predetermined criteria. The selected articles were used to answer the primary question. The searched databases, the search string or terms used during the search and selection criteria applied are listed in the chapter for each individual primary question.

Quality assessment of individual studies

Individual studies were assessed systematically based on predefined methodological quality criteria in order to assess the risk of biased study results. These assessments may be found in the column ‘Study quality assessment’ in an evidence table.

Literature summary

The relevant study results from all selected articles were presented clearly in evidence tables. The key findings from the literature are described in the literature summary. If studies were sufficiently similar in design, data were also summarized quantitatively (meta-analysis) using Review Manager 5.

Assessment of the level of scientific evidence

A) With regard to intervention questions:

The level of scientific evidence was determined using the GRADE method. GRADE is short for ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (see http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) (Atkins et al, 2004).

B) With regard to questions about the value of diagnostic tests, harm or adverse effects, etiology and prognosis:

GRADE cannot be used (yet) for these types of questions. The level of evidence of the conclusion was determined based on the accepted EBRO method (van Everdingen et al, 2004).

Formulation of conclusions

With regard to questions about the value of diagnostic tests, harm or adverse effects, etiology and prognosis, the scientific evidence is summarized in one or more conclusions, listing the level of evidence for the most relevant data.

For interventions, the conclusion does not refer to one or more articles, but is drawn based on the body of evidence. The working group looked at the net benefits of each intervention. This was done by determining the balance between favorable and unfavorable effects for the patient.

Considerations

When making recommendations, scientific evidence was considered together with other key aspects, such as working group member expertise, patient preferences, costs, availability of facilities and/or organizational aspects. Insofar as they are not part of the systematic literature review, these aspects are listed under ‘Considerations’.

Formulation of recommendations

Recommendations provide an answer to the primary question, and are based on the best scientific evidence available and the most important considerations. The level of scientific evidence and the importance given to considerations by the working group jointly determine the strength of the recommendation. In accordance with the GRADE method, a low level of evidence for conclusions in the systematic literature review does not rule out a strong recommendation, while a high level of evidence may be accompanied by weak recommendations. The strength of the recommendation is always determined by weighing all relevant arguments.

Development of indicators

Along with developing a draft guideline, internal quality indicators were developed to allow monitoring of the implementation of the guideline in daily practice. More information about the method for indicator development may be requested from KIMS.

Knowledge gaps

During the development of this guideline, systematic searches were conducted for research contributing to answering the primary questions. For each primary question, the working group determined whether (additional) scientific research is desirable.

Commentary and authorization phase

The draft guideline was submitted to the (scientific) organizations involved for comment. The guideline was also submitted to the following organizations for comment: Netherlands Breast Cancer Association (BVN), Netherlands Society for Medical Oncology (NVMO), Dutch College of General Practitioners (NHG), Healthcare Insurers Netherlands (ZN), The Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZA), Health Care Insurance Board (CvZ), the Health Care Inspectorate (IGZ), Achmea, CZ, Menzis and VGZ. Comments were collected and discussed with the working group. The draft guideline was updated and finalized by the working group based on the comments. The final guideline was submitted for authorization to the (scientific) organizations involved and authorized by them.

Legal standing of guidelines

Guidelines are not legal prescriptions, but contain evidence-based insights and recommendations that care providers must meet in order to provide high quality care. As these recommendations are primarily based on ‘general evidence for optimal care for the average patient’, care providers may deviate from the guideline based on their professional autonomy when they deem it necessary for individual cases. Deviating from the guideline may even be necessary in some situations. If care providers choose to deviate from the guideline, this should be done in consultation with the patient, where relevant. Deviation from the guideline must always be justified and documented.

Search strategy

|

Database |

Search terms |

Number of hits |

|

Medline (OVID) 1990-Feb. , Sept. 2012

|

1 exp Mastectomy/ (20577) 3 (mastectomy or mammaplasty).ti,ab. (14214) 4 exp *mammaplasty/ (5844) 5 (post$ adj6 mastectom$).ti,ab. (924) 6 or/1-5 (30204) 8 exp *Breast Implants/ (2178) 9 exp *Surgical Flaps/ (27999) 10 (breast adj6 reconstruct* adj6 surger*).ti,ab. (586) 17 (reconstruction* or flap* or dorsiflap or LD-flap or perforatorflap or DIEPflap or sGAPflap or iGAPflap or TMGflap or TRAMflap).ti,ab. (151589) 18 1 or 3 or 4 or 5 (29540) 19 8 or 9 or 10 or 17 (156333) 20 18 and 19 (5760) 21 limit 20 to (english language and yr="1990 -Current") (4155) 26 ((breast adj3 sparing) or nipple or areola or (breast adj3 conserving)).ti,ab. (9309) 27 21 not 26 (3439) 28 limit 27 to (english language and yr="1990 -Current") (3439) 63 "breast reconstruction*".ti. (2459) 64 28 and 63 (1520) 99 Transplantation, Autologous/ (40403) 100 (Autologous or "free flap*" or "perforator flap*").ti,ab. (62112) 106 autogenous.ti,ab. (9766) 107 99 or 100 or 106 (97955) 108 64 and 107 (550) 137 108 and 136 (8) – Search filter SR 138 108 not 137 (542) – 4 internal double

Additional 1 exp Mastectomy/ (21277) 2 (mastectomy or mammaplasty).ti,ab. (14731) 3 exp *mammaplasty/ (6254) 4 (post$ adj6 mastectom$).ti,ab. (969) 5 or/1-4 (30710) 6 exp *Breast Implants/ (2332) 7 exp *Surgical Flaps/ (29010) 8 (breast adj6 reconstruct* adj6 surger*).ti,ab. (628) 9 (reconstruction* or flap* or dorsiflap or LD-flap or perforatorflap or DIEPflap or sGAPflap or iGAPflap or TMGflap or TRAMflap).ti,ab. (159105) (164071) 11 5 and 10 (6133) 12 limit 11 to (english language and yr="1990 -Current") (4503) 13 ((breast adj3 sparing) or nipple or areola or (breast adj3 conserving)).ti,ab. (9745) 14 12 not 13 (3728) 15 limit 14 to (english language and yr="1990 -Current") (3728) 18 Transplantation, Autologous/ (41316) 19 (Autologous or "free flap*" or "perforator flap*").ti,ab. (64780) 20 autogenous.ti,ab. (10025) 21 or/18-20 (101204) 22 17 and 21 (600) 50 Search filter SR 71 Search filter RCT 82 15 and 21 (926) 83 limit 22 to yr="1980 - 2011" (562) 84 82 not 83 (364) (after excluding references from previous search) 85 50 and 84 (5) 86 71 and 84 (18) 93 exp epidemiological studies/ (1451366) 94 84 and 93 (115) 95 86 or 94 (121) 101 ((free adj3 TRAM) and pedicled).ti,ab. (89) – 105 95 or 101 (201) 106 limit 105 to english language (189)

|

751 |

|

Cochrane (Wiley)

|

#1 MeSH descriptor Mammaplasty explode all trees #2 (breast next reconstruction) #5 (mamma* reconstruction):ti,ab,kw #6 (#5 OR #2 OR #1) #38 MeSH descriptor Transplantation, Autologous explode all trees #39 (Autologous or "free flap*" or "perforator flap*" or autogenous):ti,ab,kw #40 (#38 OR #39) #42 (mastectomy):ti,ab,kw #43 MeSH descriptor Mastectomy explode all trees #44 (#42 OR #43) #45 (#44 OR #6) #46 (#45 AND #40) #47 (#46), from 1990 to 2012 24 references, 16 unique |