Adjuvante therapie bij pancreascarcinoom

Uitgangsvraag

Is adjuvante behandeling met chemotherapie, chemoradiotherapie of beide geassocieerd met een betere overleving en kwaliteit van leven vergeleken met resectie zonder adjuvante behandeling?

Aanbeveling

Start binnen 12 weken postoperatief adjuvante chemotherapie.

Geef patiënten met een WHO performance score van 0 of 1: 12 kuren mFOLFIRINOX (een combinatie van 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin en leucovorin).

Geef patiënten met een WHO performance score van 2, of patiënten ouder dan 75 jaar: 6 kuren gemcitabine. Overweeg capecitabine hieraan toe te voegen.

Geef geen adjuvante chemoradiotherapie.

Overwegingen

Gebaseerd op de huidige literatuur, met nadruk op survival en toxiciteit, bestaat voor patiënten die geen neoadjuvante therapie hebben gehad, de standaard adjuvante chemotherapie uit 6 cycli gemcitabine monotherapie. Studies die adjuvante behandeling met S1 hebben onderzocht, geven tegenstrijdige resultaten, waarbij in een grote RCT S1 een extra overlevingswinst van 21 maanden door S1 werd behaald in vergelijking met gemcitabine adjuvant. Deze studie is in Azië verricht, zodat extrapolatie naar onze populatie niet mogelijk is.

De resultaten van gemcitabine plus capecitabine in de ESPAC-4 studie, uitgevoerd in 6 Europese landen, toont een verbeterde mediane overleving ten opzichte van gemcitabine monotherapie. Het beschreven toxiciteitsprofiel van gemcitabine plus capecitabine is hanteerbaar. Alhoewel de langetermijn resultaten van de ESPAC-4 studie nog niet beschikbaar zijn, is de werkgroep van mening dat overwogen dient te worden om capecitabine toe te voegen aan gemcitabine.

Op basis van de PRODIGE24-studie adviseert de werkgroep om bij patiënten met een WHO performance score van 0 of 1 adjuvant gemodificeerd FOLFIRINOX te geven. In het gemodificeerde FOLFIRINOX schema (mFOLFIRINOX) wordt de bolus 5FU achterwege gelaten en wordt irinotecan naar 150 mg/m2 gereduceerd. De mediane ziektevrije overleving, primair eindpunt van de studie, was 21.6 maanden in de mFOLFIRINOX groep versus 12.6 maanden in de gemcitabine groep. De mediane totale overleving van mFOLFIRINOX was 54.4 versus 35.0 maanden in de gemcitabine groep (HR 0.64; 95% CI 0.48-0.86; P = 0.003). De 3 jaars overleving is 63% in de mFOLFIRINOX groep versus 49% in de gemcitabine groep. De incidentie van ernstige bijwerkingen was hoger in de mFOLFIRINOX groep ten opzichte van de gemcitabine groep, met 76 versus 53% CTCAE graad 3-4 bijwerkingen. Er is geen toxisch overlijden in de mFOLFIRINOX versus 1 overlijden (interstitiële pneumonitis) ten gevolge van behandeling met gemcitabine.

De bovenstaande overwegingen gelden voor zowel R0 als R1 resecties. Er zijn geen data om de adjuvante chemotherapie te herzien bij patiënten met een R1-resectie.

Er is geen plaats voor adjuvante chemoradiotherapie.

Een studie over de optimale timing van start van de adjuvante chemotherapie van Valle et al (2014) liet zien dat er geen verschil in overleving was tussen vroeg starten van adjuvante chemotherapie versus uitstel tot 12 weken postoperatief. Derhalve is het advies om binnen 12 weken na de resectie te starten, waarbij het belangrijk is de patiënten de tijd te geven om te herstellen alvorens te starten met adjuvante chemotherapie.

De sequentie van behandelingen waaronder resectie en chemotherapie zal de komende jaren uitgebreid onder de loep worden genomen.

Wat vinden patiënten: patiëntenvoorkeur

Tijdens het ziektebeloop dienen er voortdurend beslissingen te worden genomen over de toe te passen behandelingen. Patiënten platform Living With Hope Foundation (LWHF) vindt gezamenlijke besluitvorming oftewel “shared decision making” (gedeelde besluitvorming) een essentieel onderdeel van het zorgproces. Aan de hand van tools zoals de Keuzekaart, een Keuzehulp of animatievideo’s kan de behandelaar samen met de patiënt op een eenvoudige manier de opties inzichtelijk maken, zodat de patiënt in staat gesteld wordt een gewogen keuze te maken. Deze gewogen keuze kan leiden tot een andere behandeling of zelfs tot het afzien van de behandeling.

Gedeelde besluitvorming geeft bij de patiënt en zijn naasten een grotere mate van tevredenheid, gelet op de ervaren betrokkenheid bij de besluitvorming en de daarbij ervaren emotionele ondersteuning. Uitgebreide informatie over gedeelde besluitvorming is te vinden in de module 'Voorlichting en Communicatie'.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

Het pancreascarcinoom wordt gezien als een systemische ziekte, niet alleen gebaseerd op het hoge percentage patiënten dat zich met gemetastaseerde ziekte presenteert, maar tevens op basis van het hoge percentage snelle recidieven na (radicale) resectie. Derhalve is (adjuvante) chemotherapie een belangrijk onderdeel van de behandeling van het pancreascarcinoom. Het naar voren halen van de systemische behandeling naar de neo-adjuvante setting zal de komende periode worden geëvalueerd. Vooralsnog is de standaard behandeling een resectie, gevolgd door adjuvante chemotherapie.

Conclusies / Summary of Findings

|

High GRADE

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil or gemcitabine reduces the risk of mortality after surgery by about a third compared to no adjuvant treatment.

Bronnen: Xu 2017; Liao 2013 |

|

Low GRADE

|

Adjuvant chemotherapy regimens probably do not lengthen the average survival time compared to gemcitabine chemotherapy, except for adjuvant S-1 treatment or adjuvant gemcitabine plus capecitabine treatment. There are indications that these adjuvant treatments might lengthen the average survival time compared to adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy.

Bronnen: Xu 2017; Liao 2013 |

|

Moderate GRADE |

Adjuvant chemoradiation is not likely to reduce the risk of mortality after surgery.

Bronnen: Xu 2017; Liao 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Adjuvant chemoradiation plus chemotherapy reduces the risk of mortality after surgery probably not.

Bronnen: Liao 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Chemoradiation is probably the least toxic adjuvant treatment, chemotherapy is probably a more toxic adjuvant treatment and chemoradiation plus chemotherapy is probably the most toxic adjuvant treatment.

S-1 chemotherapy is probably the least toxic chemotherapy, whereas gemcitabine plus capecitabine is the most toxic chemotherapy.

Bronnen: Xu 2017; Liao 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Both adjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant chemoradiation probably lengthen the relapse-free survival time with a few months compared to no adjuvant treatment.

Other chemotherapy regimens probably do not lengthen the average relapse-free survival time compared to gemcitabine chemotherapy.

Bronnen: Xu 2017; Liao 2013 |

|

Low GRADE |

Adjuvant S-1 chemotherapy provides probably on average an additional 2.5 quality-adjusted life months and 3.3 quality adjusted relapse free life months within a 2-year time period from the time of resection than gemcitabine chemotherapy.

Bronnen: Hagiwara 2018 |

|

Low GRADE |

Adjuvant chemotherapy provides probably on average an additional 1.0 quality-adjusted life months within a 2-year time period from the time of resection.

Bronnen: Carter 2009 |

|

Low GRADE |

Adjuvant chemoradiation provides probably on average 1.0 quality-adjusted life months less within a 2-year time period from the time of resection.

Bronnen: Carter 2009 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Adjuvant treatments compared to observation only

Adjuvant treatments compared to observation only were studied in several trials: ESPAC-1 (Neoptolemos 2001; Neoptolemos 2004; a total of 545 patients among 3 subgroups), ESPAC-1+ (Neoptolemos 2009a), ESPAC-3v1 (Neoptolemos 2009b, n=314 in ESPAC-1+ and ESPAC-3v1 combined), CONKO-001 (Oettle 2007; Oettle 2013, n=354), JSAP-02 (Ueno 2009; n=118) and the earlier trial by JSAP (Kosuge 2006; n=89), , and EORTC 40891 (Smeenk 2007; n=120) and the trial by Kalser (1985) (detailed description of studies in Liao 2013) (Table 1).

After Oettle (2013) no studies comparing adjuvant therapy to surgery alone were published. Oettle (2013) described the long-term follow-up results of the CONKO-001 trial, in which adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine was compared with observation only. With adjuvant therapy as the standard of care (in the Netherlands: GEM), the opportunity to compare adjuvant treatment against observation alone, within the context of a randomized trial format, may not be repeated.

Hazard ratios (HRs) were explicitly reported in five studies and could be estimated by Liao (2013) in three studies. One study (Kalser 1985) reported median survival durations. The ESPAC-1 trial included three subgroups; for the subgroup with two-by-two factorial design Liao (2013) used the overall survival updated in a later report (Neoptolemos 2004) in the analysis. One publication (Neoptolemos 2009) reported composite data of ESPAC-1, ESPAC-1+, and ESPAC-3 v1, thus Liao (2013) included only data from ESPAC-1+ and ESPAC-3 v1 to avoid duplication. We extracted HRs from Liao (2013) and used the results of long-term follow-up of Oettle (2013) instead of their earlier results (Oettle 2007). For toxic effects, Liao (2013) compared the five adjuvant treatments and calculated odds ratios (ORs) from the number of total patients and the number of patients with toxic effects in each trial for meta-analysis.

Table 1 Details of the studies comparing adjuvant treatments and observation only

|

Study |

Studypopulation (n) |

Intervention |

|

CONKO-001 (Oettle 2007; Oettle 2013) |

354 |

Chemotherapy with gemcitabine |

|

ESPAC-1+ (Neoptolemos 2009a) ESPAC-3v1 (Neoptolemos 2009b) |

314 |

Chemotherapy with 5FU |

|

JSAP-02 (Ueno 2009) |

118 |

Chemotherapy with gemcitabine |

|

EORTC 40891 (Smeenk 2007) |

120 |

Chemoradiation |

|

JSAP (Kosuge 2006) |

89 |

Chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-FU |

|

ESPAC-1 (Neoptolemos 2001; Neoptolemos 2004) |

545 |

Subgroups: Chemotherapy with 5FU Chemoradiation |

|

Kalser 1985 |

43 |

Combined radiation and 5FU |

Adjuvant chemotherapy compared to adjuvant gemcitabine chemotherapy

Xu (2017) compared in a network meta-analysis all adjuvant chemotherapy treatments: a total of nine chemotherapy regimens including S-1, fluorouracil (5FU), gemcitabine(gemcitabine), gemcitabine plus capecitabine, 5FU plus chemoradiation (CRT), gemcitabine plus CRT, cisplatin plus epirubicin plus 5FU plus gemcitabine plus CRT, gemcitabine plus uracil/tegafur and 5FU plus cisplatin were involved (Xu 2017). Xu (2017) reported five trials in which the control group received gemcitabine treatment: ESPAC-4 (Neoptolemos 2017), JASPAC01 (Uesaka 2016; Hagiwara 2018), Shimoda (2015), ESPAC-3v2 (Neoptolemos 2010), and Yoshitomi (2008). An overview of the studies relevant for answering the PICO on adjuvant chemotherapy is presented in table 2.

Table 2. Details of the studies comparing adjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine

|

Study |

Studypopulation (n) |

Intervention |

|

ESPAC-4 (Neoptolemos 2017) |

700 |

gemcitabine vs gemcitabine plus capecitabine |

|

JASPAC01 (Uesaka 2016; Hagiwara 2018) |

377 |

gemcitabine vs S-1 |

|

Shimoda 2015 |

57 |

gemcitabine vs S-1 |

|

ESPAC-3v2 (Neoptolemos 2010) |

1088 |

GE vs 5FU |

|

Yoshitomi 2008 |

99 |

gemcitabine vs gemcitabine plus uracil/tegafur |

Results

1.1 Adjuvant chemotherapy compared to observation only

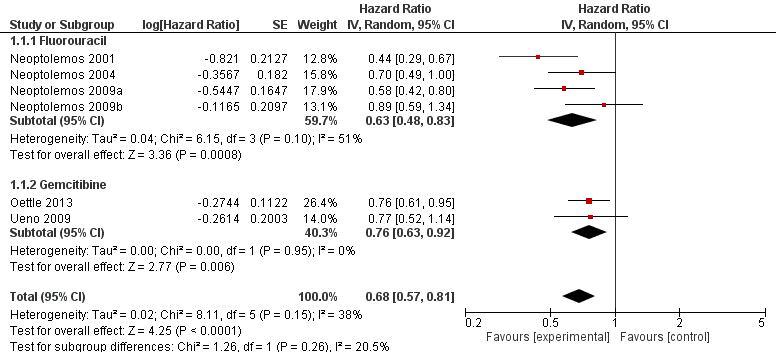

1.1.1 Overall survival (critical outcome)

Both adjuvant chemotherapy with 5FU or gemcitabine decreased overall mortality (see Figure 1) compared to observation only after surgery. Pooled results for both adjuvant chemotherapy treatments showed an HR of 0.68 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.81), indicating that adjuvant chemotherapy decreased the risk of mortality after surgery by about a third. Kosuge (2006) evaluated the effect of adjuvant cisplatin and 5FU therapy after curative resection among a total of 89 patients. They found that median survival was 15.8 months in the surgery-alone group and 12.5 months in the surgery + chemotherapy group, and the 5-year survival rate was 14.9% in the surgery-alone group and 26.4% in the surgery + chemotherapy group (p = 0.94).

Figure 1. Pooled hazard ratios for death by traditional meta-analysis (adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation).

1.1.2 Relapse-free survival

Available data on relapse-free survival are presented in Table 3. The median time to relapse ranges from 10.2 to 13.4 months for patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. For patients receiving only surgery, the median time to relapse ranges from 5 to 8.6 months.

Table 3. Relapse free survival (median time, 95% CI) (adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation)

|

Study |

Median time (months) intervention vs control |

95% CI |

|

Oettle 2013 |

13.4 vs 6.7 |

11.6-15.3 vs 6.0-7.5 |

|

Ueno 2009 |

11.4 vs 5.0 |

8.0-14.5 vs 3.7-8.9 |

|

Neoptolemos 2009 |

NA |

NA |

|

Kosuga 2006 |

10.2 vs 8.6 |

not reported |

|

Neoptolemos 2004 |

NA |

NA |

1.1.3 Toxicity

A total of 70 patients receiving adjuvant treatment with 5FU or gemcitabine (of a total of 334 patients receiving adjuvant treatment in 4 studies, 21%) experienced grade 3-4 toxic effects. Liao (2013) calculated an estimated odds of 0.33 in favour of 5FU compared to gemcitabine, but this difference in the proportion of patients experiencing toxic effects was not statistically significant different (OR 0.33; 95% CI 0.03 to 4.29).

1.1.4 Quality of Life (critical outcome)

Carter (2009) calculated Quality adjusted life months (QALM) over 24 months. For the chemotherapy group, the QALM-24 was 9.6 (95% CI: 8.7 to 11.2) months compared with the mean QALM-24 of 8.6 (95% CI: 7.6, 10.5) months for the no chemotherapy group.

Rating of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome

The quality of the evidence comparing adjuvant chemotherapy to observation only:

- was ‘High’ for the outcomes ‘overall survival’ and ‘relapse free survival’;

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘toxicity’. Reasons for downgrading the body of evidence were: clinical heterogeneity, imprecision (the confidence interval crossing 1) and indirectness (no direct comparisons for all adjuvant treatments with observation only);

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘quality of life’. Reasons for downgrading the body of evidence were some methodological limitations (incomplete QoL data accrual and fallout through death) and serious imprecision (results from one study and a (relatively) small number of patients randomized).

There was no indication of publication bias.

1.2. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine

1.2.1 Overall survival (critical outcome) (Table 4)

One large RCT (n=377) (Uesaka 2016) suggested that S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy prolonged the median survival (46.5 months, 95% CI 37.8 to 63.7) in Asian patients compared to gemcitabine adjuvant therapy (25.5 months, 95% CI 22.5 to 29.6; HR 0.57, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.72). One smaller RCT including 57 patients (Shimoda 2015) did not find a beneficial effect of S-1 treatment compared to gemcitabine in terms of overall survival (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.36, p=0.293).

Gemcitabine plus capecitabine also showed a favourable effect on mortality (HR=0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.98) (Neoptolomos 2017).

Overall survival after treatment with gemcitabine plus uracil/tegafur or fluorouraciI alone was not statistically significant different compared to gemcitabine alone (Neoptolemos 2010; Yoshitomi 2008). Furthermore, the network meta-analysis of Xu (2017) showed that chemotherapy plus 5FU or gemcitabine is inferior to 5FU or gemcitabine alone in terms of overall survival.

|

Study |

Intervention |

Median time (months) intervention vs gemcitabine |

95% CI |

5 yr survival (frequency, %) |

|

Neoptolemos 2017 |

gemcitabine plus capecitabine vs gemcitabine |

28.0 vs 25.5 |

23.5-31.5 vs 22.7-27.9 |

19/364 (5.2%) vs 9/336 (2.7%) |

|

Uesaka 2016 |

S-1 vs gemcitabine |

46.5 vs 25.5 |

37.8-63.7 vs 22.5-29.6 |

80/187 (42.8%) vs 45/190 (23.7%) |

|

Shimoda 2015 |

S-1 vs gemcitabine |

21.5 vs 18.0 |

14.4-42.5 vs 3.3-42. |

Not applicable |

|

Neoptolemos 2010 |

5FU vs gemcitabine |

23.0 vs 23.6 |

21.1-25 vs 21.4-26.4 |

15/551 (2.7%) vs 13/537 (2.4%) |

|

Yoshitomi 2008 |

gemcitabine plus uracil/tegafur vs gemcitabine |

21.2 vs 29.8 |

not reported |

Not applicable |

Table 4. Overall survival (median time, 95% CI) comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine.

* Estimated data, awaiting long term results

1.2.2 Relapse-free survival

Uesaka (2016) reported a median relapse free survival time of 22.9 months (95% CI 17.4 to 30.6) after S-1 adjuvant treatment compared to 11.3 months (9.7 to 13.6) after adjuvant gemcitabine treatment. Shimoda (2015) found that after S-1 adjuvant treatment relapse-free survival tended to be longer compared to gemcitabine, but the 4-month difference was not statistically significant (Table 3). Other adjuvant treatments did not result in a longer relapse-free survival time.

Table 5. Relapse free survival (median time, 95% CI) (adjuvant chemotherapy versus adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine)

|

Study |

Other adjuvant treatment (intervention) |

Median time (months) intervention vs gemcitabine |

95% CI |

|

Neoptolemos 2016 |

gemcitabine plus capecitabine |

13.9 vs 13.1 |

95% CI 12.1-16.6 vs 11.6-15.3 |

|

Uesaka 2016 |

S-1 |

22.9 vs 11.3 |

95% CI 17.4-30.6 vs 9.7-13.6 |

|

Shimoda 2015 |

S-1 |

14.6 vs 10.5 |

90% CI 8.8-28.4 vs 7.0-28.4 |

|

Neoptolemos 2010 |

5FU |

14.1 vs 14.3 |

95% CI 12.5-15.3 vs 13.5-15.6 |

|

Yoshitomi 2008 |

gemcitabine plus uracil/tegafur |

12.3 vs 12 |

not reported |

1.2.3 Toxicity

The network meta-analysis of Xu (2017) showed that S-1 chemotherapy ranked the least toxic, whereas gemcitabine plus capecitabine ranked the most toxic. 5FU showed more toxic events than in the group of gemcitabine. In table 4 the number of patients experiencing toxic effects are shown for each adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 6. Toxicity (number of patients experiencing toxic effects (adjuvant chemotherapy versus adjuvant treatment with gemcitabine)

|

Study |

Other adjuvant treatment (intervention) |

Overall grade 3–4 toxic effects (n) intervention vs gemcitabine |

|

Neoptolemos 2016 |

gemcitabine plus capecitabine |

226 vs 196 |

|

Uesaka 2016 |

S-1 |

26 vs 138 |

|

Shimoda 2015 |

S-1 |

6 vs 15 |

|

Neoptolemos 2010 |

5FU |

379 vs 221 |

|

Yoshitomi 2008 |

gemcitabine plus uracil/tegafur |

12 vs 15 |

1.2.4 Quality of Life (critical outcome)

Neoptolemos (2010) reported quality of life (QoL) within a 12-month duration from surgery for patients receiving 5FU compared with those receiving gemcitabine. They found no statistically significant differences in mean standardized area under the curve scores for global quality-of-life scores across treatment groups conditional on patient survival; mean standardized AUC was 43.6 (SD 20.1) for patients receiving 5FU (plus folinic acid), compared with 46.6 (SD 19.7) for those receiving gemcitabine (p=0.08).

Hagiwara (2018) reported, based on per-protocol analyses, that health-related QoL within 6 months from treatment initiation was comparable between the patients receiving S-1 and gemcitabine, but it was better thereafter in the S-1 group. QALM-24 and Quality adjusted relapse free months (QARFM-24), measures that simultaneously take survival outcomes and QOL into account, were both longer in the S-1 group (17.3, 95% CI 16.5 to 18.2 and 14.6, 95% CI 13.6 to 15.7, respectively) than in the gemcitabine group (14.8, 95% CI 13.9 to 15.7 and 11.3, 95% CI 10.3 to 12.3, respectively). The difference in QALM-24 was 2.5 months in favour of S-1 (95% CI 1.3 to 3.8, p < 0.001) and in QARFM-24 the difference was 3.3 months in favour of S-1 (95% CI 1.9 to 4.8, p < 0.001).

Rating of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome

The quality of the evidence comparing adjuvant chemotherapy to adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine:

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcomes ‘overall survival’ ‘and ‘relapse free survival’ for all other adjuvant treatments compared to gemcitabine. Reasons for downgrading the body of evidence were: clinical heterogeneity (regarding S1, with one study in an Asian population showing an inexplicable large effect, and another study showing no effect), and serious imprecision (regarding other adjuvant treatments with results originating from single studies).

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Moderate’ for the outcome ‘toxicity’ due to clinical heterogeneity and some studies showing more toxic events than gemcitabine and others less events.

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘quality of life’. Reasons for downgrading the body of evidence were some methodological limitations (incomplete QoL data accrual and fallout through death) and clinical heterogeneity.

There was no indication of publication bias.

2. Adjuvant chemoradiation compared to observation only

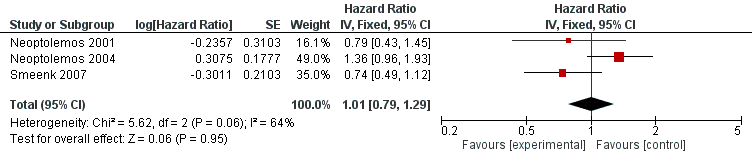

2.1 Overall survival (critical outcome)

In three publications the effect of 5FU-based chemoradiation after surgery compared to no adjuvant treatment on mortality was reported. Estimated effects were both negative and positive. Pooled results showed no survival advantage of adjuvant chemoradiation therapy (HR 1.01; 95% CI: 0.79 to 1.29).

Figure 2. Pooled hazard ratios for death by traditional meta-analysis (adjuvant 5FU-based chemoradiation versus observation).

2.2 Relapse-free survival

Smeenk (2007) reported a median relapse free survival period of 18 months (95% CI 12 to 21.6) in the intervention group versus 14.4 months (95% CI 10.8 to 20.4) in the observation only group.

2.3 Toxicity

A total of 12 patients receiving adjuvant chemoradiation (of a total of 136 patients receiving this adjuvant treatment in 2 studies, 9%) experienced grade 3-4 toxic effects. Liao (2013) calculated that chemoradiation was ranked as the least toxic adjuvant treatment.

2.4 Quality of Life (critical outcome)

Carter (2009) studied a subset of ESPAC-1 patients (n=316) and calculated for the chemoradiation group a mean QALM-24 of 7.1 (95% CI: 6.0 to 9.0) months compared with a mean QALM-24 of 8.1 (95% CI: 7.0 to 10.0) months for the no chemoradiation group.

Rating of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome

The quality of the evidence comparing adjuvant chemoradiation to observation only:

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Moderate’ for the outcome ‘overall survival’. The risk of bias due to methodological constraints was considered to be low (Xu 2017; Liao 2013). However, the quality of the evidence was downgraded one level due to some unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2=64%).

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘relapse-free survival’ due to serious imprecision (results from one study and hence, a small sample size).

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘toxicity’ due to serious imprecision (few patients involved).

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘quality of life’. Reasons for downgrading the body of evidence were some methodological limitations (incomplete QoL data accrual and fallout through death) and serious imprecision (results from one study).

3. Adjuvant chemoradiation plus chemotherapy compared to observation only

3.1 Overall survival (critical outcome)

One study assessed the effect of chemoradiation plus 5FU versus observation. No studies compared chemoradiation plus gemcitabine with observation only.

In 1985, the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group (GITSG) randomized a total of 43 patients to surgery alone or additional chemoradiotherapy followed by chemotherapy. The median survival was significantly longer in the adjuvant treatment group (20 months vs 11 months), with resp. 43% and 18% survival after 2 years and 18% and 8% after 5 years (Kalser 1985). The study was terminated after the inclusion of only 43 patients due to poor accrual and it was unclear whether the improved survival was due to chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy alone.

Liao (2013) presented the results of studies comparing chemoradiation plus 5FU or gemcitabine with other adjuvant treatments. Liao (2013) found no survival advantage over chemoradiation plus 5FU compared to chemoradiation alone (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.19 to 1.74) or chemotherapy with 5FU alone (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.27 to 2.69). No effect (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.40-1.71) for chemoradiation plus gemcitabine compared to chemoradiation plus 5FU was found either.

3.2 Relapse-free survival

Not reported.

3.3 Toxicity

In the GITSG study a total of 3 patients (3/22; 14%) in the intervention group experienced toxic effects. Liao (2013) calculated (based on mutual comparisons) that chemoradiation plus gemcitabine or 5FU was most likely to be ranked the worst or second worst in terms of overall toxic effects, with estimated ORs ranging from 1.61 (when compared to chemotherapy with 5FU) to 27.80 (when compared to chemoradiation).

3.4 Quality of Life

No RCTs reporting on quality of life measures for patients receiving adjuvant chemoradiation plus chemotherapy were found.

Rating of the overall quality of evidence for each outcome

The quality of the evidence comparing adjuvant chemoradiation plus chemotherapy compared to observation only:

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Very low’ for the outcome ‘overall survival’ due to methodological constraints (terminated inclusion), serious imprecision and indirectness (only one trial assessing the direct effect and few patients involved).

- was lowered from ‘High’ to ‘Low’ for the outcome ‘toxicity’ due to serious imprecision (few patients involved) and indirect comparisons.

- No evidence was found reporting the outcomes ‘relapse free survival’ and ‘quality of life’.

Zoeken en selecteren

In order to answer the clinical question (‘uitgangsvraag’), we performed a systematic literature search for the following research question(s):

Is adjuvant therapy associated with better survival and quality of life compared to no adjuvant therapy?

P Patients with pancreatic cancer

I Adjuvant radiotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy, or both

C Surgery only or current care-as-usual, i.e. gemcitabine

O Survival, toxicity (number of patients experiencing toxic effects), relapse-free survival, quality of life (QoL)

Relevant outcome measures

The working group decided that survival and quality of life were crucial outcome measure for decision-making and toxicity, relapse-free survival as important outcome measures for decision-making. The working group did not define the mentioned outcome measures beforehand, however, they used the definitions described in the studies.

Zoeken en selecteren (Methode)

The information specialist searched the databases Medline (via OVID), Embase (via Embase.com) and the Cochrane Library (via Wiley)] on 23rd November 2017, relevant search terms were used to search for English-language systematic reviews (SRs) on adjuvant therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer published from 2010 The search acknowledgement can be found in the tab Acknowledgement.

This literature search yielded 212 hits. Studies were selected on the basis of the following selection criteria:

- Study population concerns patients with pancreatic cancer;

- The intervention is adjuvant radiotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy or both;

- Concerns systematic review.

On the basis of title and abstract, 15 articles were initially pre-selected. After consulting the full text, 13 studies were then excluded (see exclusion table in the tab Acknowledgement), and 2 SRs were finally selected: Xu (2017) and Liao (2013). Xu (2017) was the most recent SR (search till November 2016) and it was decided to search for randomized controlled trials on the topic published in 2016 or later.

The information specialist searched the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) on 30th April 2018, relevant search terms were used to search for English-language RCTs on adjuvant therapy in patients with pancreatic cancer. Details of the search strategy can be found in the tab Acknowledgement. This literature search yielded 212 studies published from 2016 onwards. Studies were selected on the basis of the following selection criteria:

- Study population concerns patients with pancreatic cancer;

- The intervention is adjuvant radiotherapy, adjuvant chemotherapy or both;

- Concerns primary (original) comparative research (RCT).

On the basis of title and abstract, two articles were initially pre-selected. After consulting the full text, one study was finally selected: Hagiwara (2018). The other selected study was already included in the SR of Xu (2017).

The most important study characteristics and results are shown in the evidence tables. The judgement of the individual study quality (risk of bias) is shown in the risk of bias tables.

The systematic review of Liao (2013) provided a more comprehensive description of all trials and articles and data were extracted from this review. Data were supplemented with the more recent publication of Oettle (2013). Xu (2017) and Liao (2013) reported overall survival, relapse free survival and toxicity. Therefore, the literature was checked for publications describing the outcome ‘quality of life’ that originated from the trials described in Xu (2017).

Referenties

- Carter R, Stocken DD, Ghaneh P, et al. Longitudinal quality of life data can provide insights on the impact of adjuvant treatment for pancreatic cancer-Subset analysis of the ESPAC-1 data. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(12):2960-5.

- Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(25):2395-2406.

- Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg. 1985;120(8):899-903.

- Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1473-81.

- Valle JW, Palmer D, Jackson R, et al. Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):504-12.

- Xu JB, Jiang B, Chen Y, et al. Optimal adjuvant chemotherapy for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(46):81419-81429.

Evidence tabellen

Research question: Is adjuvante behandeling met chemotherapie, radiotherapie of beide geassocieerd met een betere overleving en kwaliteit van leven vergeleken zonder adjuvante behandeling of standaard behandeling (i.e. gemcitabine)? (Wat zijn de voor- en nadelen van chemotherapie, radiotherapie of beide na resectie vergeleken met resectie alleen?)

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies [cohort studies, case-control studies, case series])

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics 2 |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C) 3

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size 4 |

Comments |

|

Oettle 2013 (CONKO-001) |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Hospital

Country: Germany

Source of funding: Supported in part by a grant from Lilly Germany. The study was further supported by the German Cancer Society (section AIO) and promoted by a research grant from the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin. CONKO-001 was an investigator-initiated trial. |

Inclusion criteria: Age 18 years or older, a Karnofsky Performance Status Scale score of 50% or higher, adequate bone marrow function (defined as white blood cell count ≥3500 cells/μL, platelet count ≥100 000 cells/μL, and hemoglobin level ≥80 g/L), anticipated patient adherence to treatment, and adherence to longterm follow-up for at least 2 years after surgery.

Exclusion criteria: Received neoadjuvant therapy, had active infection, had impaired coagulation, etc.

N total at baseline: 368 Intervention: 186 Control: 182

The major baseline characteristics of eligible patients were well balanced across study groups |

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

Adjuvant gemcitabine treatment

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Observation alone |

Length of follow-up: Every 8 weeks for up to 5 years or until death. Median: 136 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Intervention: N (%) = 7 Reasons 4 Withdrew consent 1 Another malignant disease (rectal carcinoma 1 No histologic verification 1 Persistent disease

Control: N (%) = 7 Reasons 4 Withdrew consent 2 Papillary carcinoma 1 Adenocarcinomatous distal duct cholangiocarcinoma

Incomplete outcome data: Intervention: N (%) Reasons (describe)

Control: N (%) Reasons (describe)

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

354 patients were eligible for intention-to-treat-analysis I: 179 C: 175

Overall survival (median months) HR = 0.76 [95% CI, 0.61-0.95]; P = .01)

5-year overall survival I: 20.7% (95% CI, 14.7%-26.6%) C: 10.4% (95% CI, 5.9%-15.0%)

10-year overall survival I: 12.2% (95% CI, 7.3%-17.2%) C: 7.7% (95% CI, 3.6%-11.8%)

Disease-free survival* (median months) I: 13.4 (95% CI, 11.6-15.3) C: 6.7 (95% CI, 6.0-7.5) HR: 0.55 [95% CI, 0.44-0.69]; p < .001) * date of randomization to the date of first documentation of recurrence (with cytological or histological confirmation or with radiological evidence). |

The CONKO-001 data show that among patients with macroscopic complete removal of pancreatic cancer, the use of adjuvant gemcitabine for 6 months compared with observation resulted in increased overall survival as well as disease-free survival. |

|

Carter 2009 (ESPAC-1) |

Type of study: RCT

Setting: Hospital

Country: Europe

Source of funding: Cancer Research UK and Ministero dell' Istruzione e della Ricerca. Grant Number: 2003063754

|

Inclusion criteria: not reported in this publication

Exclusion criteria: not reported in this publication

N total at baseline: 550 N=137 chemotherapy N=126 no chemotherapy

N=90 chemoradiation N=114 no chemoradiation

|

Describe intervention (treatment/procedure/test):

i) adjuvant chemotherapy and (ii) adjuvant chemoradiation

|

Describe control (treatment/procedure/test):

Observation alone |

Length of follow-up: 24 months

Loss-to-follow-up: Incomplete data capture resulted from either death within the study period or non-returned forms including 77 (24%) patients failed to complete baseline forms and were not included in the statistical analysis. There were more patients with missing baseline forms in the group randomized to no chemotherapy [36 (29%) vs. 28 (20%)] and equal proportions in the chemoradiation and no chemoradiation groups [23 (26%) vs. 30 (26%)].

|

Outcome measures and effect size (include 95%CI and p-value if available):

Included in statistical analysis: At baseline: N=239 At 24 months: N=42

Quality of Life (EORTC QLQ-C30) (Higher scores for the functional and global health scales indicated better QoL whereas higher scores for the symptom scales and items indicated poorer QoL)

Quality Adjusted Life Months over 24 months (QALM-24) i) Chemotherapy vs observation I: 9.6 (95% CI: 8.7, 11.2) C: 8.6 (95% CI: 7.6, 10.5)

2) Chemoradiation vs observation I: 7.1 (95% CI: 6.0, 9.0) C: 8.1 (95% CI: 7.0, 10.0)

|

Chemotherapy provided on average an additional 1.0 quality-adjusted life months within a restricted 2-year time period from the time of resection. |

Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, Hartmann JT, Gellert K, Ridwelski K, Niedergethmann M, Zülke C, Fahlke J, Arning MB, Sinn M, Hinke A, Riess H. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013 Oct 9;310(14):1473-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201.

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea et al.; 2007, BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher et al 2009, PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Oettle 2013 |

Patients were randomized between adjuvant chemotherapy and observation in a 1:1 ratio using computer-generated random numbers generated at the study coordination center at the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. At randomization, the patients were stratified according to tumor stage (T1-2 vs T3-4), nodal status (N0 vs N1), and resection status (R0 vs R1), based on the TNM classification. |

Unlikely |

Unlikely (as survival is the main outcome measure) |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear: toxicity results not reported |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Verantwoording

Beoordelingsdatum en geldigheid

Publicatiedatum : 04-04-2019

Beoordeeld op geldigheid : 03-06-2019

Voor het beoordelen van de actualiteit van deze richtlijn is de werkgroep niet in stand gehouden. Uiterlijk in 2024 bepaalt het bestuur van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Heelkunde (NVvH) of de modules van deze richtlijn nog actueel zijn. Op modulair niveau is een onderhoudsplan beschreven. Bij het opstellen van de richtlijn heeft de werkgroep per module een inschatting gemaakt over de maximale termijn waarop herbeoordeling moet plaatsvinden en eventuele aandachtspunten geformuleerd die van belang zijn bij een toekomstige herziening (update). De geldigheid van de richtlijn komt eerder te vervallen indien nieuwe ontwikkelingen aanleiding zijn een herzieningstraject te starten.

Op modulair niveau moet in 2019 gekeken worden of de module ‘Screening' herzien moet worden naar aanleiding van het uitkomen van de update van de internationale consensus guideline over pancreassurveillance (Canto 2013). De module ‘Neoadjuvante behandeling van (borderline) resectabel pancreascarcinoom’ moet worden beoordeeld zodra de resultaten van de PREOPANC-1 studie zijn gepubliceerd. De module ‘Adjuvante therapie’ moet worden beoordeeld zodra de lange termijn data van lopend onderzoek (gemcitabine capecitabine, MFOLFIRINOX, nab-paclitaxel/gem) zijn gepubliceerd.

De NVvH is regiehouder van deze richtlijn en eerstverantwoordelijke op het gebied van de actualiteitsbeoordeling van de richtlijn. De andere aan deze richtlijn deelnemende wetenschappelijke verenigingen of gebruikers van de richtlijn delen de verantwoordelijkheid en informeren de regiehouder over relevante ontwikkelingen binnen hun vakgebied.

|

Module |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

|

Screening |

2020 |

|

Diagnostische strategie |

2024 |

|

Screening en diagnostiek voedingstoestand |

2024 |

|

Indicatie resectie |

2024 |

|

Voeding in het peri-operatieve beleid |

2024 |

|

Peri-operatief gebruik Somatostatine (analogen) |

2024 |

|

Uitgebreidheid resectie |

2024 |

|

Follow-up na resectie |

2024 |

|

Pancreasenzymen, vitaminen, omega-3 vetzuren en kurkuma |

2024 |

|

Pathologie |

2024 |

|

Neoadjuvante behandeling van (borderline) resectabel pancreascarcinoom |

2021 of na publicatie PREOPANC-1 studie |

|

Adjuvante therapie |

2021 of na publicatie van lange termijn data van lopend onderzoek (gemcitabine capecitabine, MFOLFIRINOX, nab-paclitaxel/gem) |

|

Behandeling van lokaal gevorderd pancreascarcinoom |

2024 |

|

Behandeling voor patiënten met gemetastaseerd pancreascarcinoom |

2024 |

|

Preoperatief en palliatief stenten |

2024 |

|

Behandelvoorkeur bij pijnbestrijding voor lokaal uitgebreid pancreascarcinoom |

2024 |

|

Voeding in de palliatieve fase |

2024 |

|

Psychosociale zorg |

2024 |

|

Voorlichting en communicatie |

2024 |

|

Organisatie van zorg |

2024 |

Algemene gegevens

De richtlijnontwikkeling werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijn.

Doel en doelgroep

Doel

Het doel van de richtlijn is om het beleid bij patiënten te standaardiseren en af te stemmen op de wensen van deze patiënten in alle fasen van hun ziekte en aanbevelingen zo te formuleren dat zij implementeerbaar zijn.

Doelgroep

Deze richtlijn is geschreven voor alle leden van de beroepsgroepen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met pancreascarcinoom, zoals chirurgen, radiotherapeuten, medisch oncologen, maag-darm-leverartsen, radiologen, nucleair-geneeskundigen, pathologen, huisartsen, oncologieverpleegkundigen, IKNL-consulenten, maatschappelijk werkers, diëtisten en psychologen.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijn is in 2017 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met een pancreascarcinoom.

De werkgroepleden zijn door hun beroepsverenigingen gemandateerd voor deelname.

De werkgroep is verantwoordelijk voor de integrale tekst van deze richtlijn.

- prof. dr. O.R.C. (Olivier) Busch, HPB chirurg, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam (voorzitter)

- C.J.M. (Charlotte) van den Bosch MSc, diëtist chirurgie-oncologie, Amsterdam UMC locatie VUmc (vanaf 1/5/2018)

- dr. L.A.A. (Lodewijk) Brosens, patholoog, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht en RadboudUMC, Nijmegen

- prof. dr. M.J. (Marco) Bruno, afdelingshoofd MDL, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam

- L.J.P.M. (Lieke) Corpelijn, verpleegkundig specialist, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- prof. dr. P. (Paul) Fockens, hoofd afdeling MDL, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam

- dr. B. (Bas) Groot Koerkamp, HPB chirurg en epidemioloog, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam

- drs. E.J.R.J. (Erik) van der Hoeven, abdominaal radioloog, St. Antonius Ziekenhuis, Nieuwegein

- dr. C. (Casper) Jansen, klinisch patholoog, LabPON, Hengelo

- de heer L. (Leo) Kwakkenbos, ervaringsdeskundige

- M. (Marjan) Mullers MSc, diëtist chirurgie-oncologie, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- dr. J.J. (Joost) Nuyttens, radiotherapeut, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam

- drs. T.P. (Thomas) Potjer, klinisch geneticus, LUMC, Leiden

- dr. M.W.J. (Martijn) Stommel, HPB chirurg, Radboudumc, Nijmegen

- drs. G. (Geertjan) van Tienhoven, radiotherapeut oncoloog, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam

- drs. J. (Judith) de Vos – Geelen, medisch oncoloog, Maastricht UMC, Maastricht

- dr. J.W. (Hanneke) Wilmink, internist-oncoloog, Amsterdam UMC locatie AMC, Amsterdam

- J.E. (Jill) Witvliet-van Nierop MSc, diëtist chirurgie-oncologie, Amsterdam UMC locatie VUmc (tot 1/5/2018)

Met ondersteuning van

- Dr. J.S. (Julitta) Boschman, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- M. (Michiel) Oerbekke MSc, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. W.A. (Annefloor) van Enst, senior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- D.P. (Diana) Gutierrez, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- J. (Jill) Heij, projectsecretaresse, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De KNMG-code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement, kennisvalorisatie) hebben gehad. Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

prof. dr. O.R.C. (Olivier) Busch |

HPB chirurg |

Geen andere betaalde functies |

Voorzitter Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group (DPCG)

Voorzitter Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Audit (DPCA bij DICA)

Lid toetsingscommissie dataverificatie DPCA

Coördinator bij PancreasParel, biobanking bij Parelsnoer Instituut |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

dr. B. (Bas) Groot Koerkamp |

HPB chirurg Epidemioloog |

Bestuurslid Wetenschappelijke vereniging van de DPCG (Ducth Pancreas Cancer Group), onbetaald |

Subsidie van ZonMW (300.000 Euro) voor fase 3 trial naar neoadjuvante FOLFIRINOX versus direct opereren en adjuvante chemotherapie voor patiënten met (borderline) resectabel pancreascarcinoom.

Subsidie van KWF (600.000 Euro) voor fase 3 trial naar intra-arteriele chemotherapie met een pomp voor patiënten resectabele colorectale levermetastase. |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

dr. M.W.J. (Martijn) Stommel |

HPB chirurg |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

dr. J.W. (Hanneke) Wilmink |

Internist-oncoloog |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Bestuurslid van de Dutch Pancreatic Cancer Group (DPCG)

Heeft extern gefinancierd onderzoek, maar de financier daarvan heeft geen belang bij resultaat van het onderzoek |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

drs. J. (Judith) de Vos – Geelen |

Medisch oncoloog |

Lid van de wetenschappelijke commissie DPCG |

Lid adviescommissie Celgene, Baxalta en Ipsen. Geen directe financiële belangen in een farmaceutisch bedrijf. |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

dr. L.A.A. (Lodewijk) Brosens |

Patholoog |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

dr. C. (Casper) Jansen |

Klinisch patholoog |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

drs. E.J.R.J. (Erik) van der Hoeven |

Abdominaal radioloog |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

prof. dr. P. (Paul) Fockens |

Hoofd afdeling MDL |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Consultancy op onregelmatige basis voor biomedische bedrijven. In de afgelopen 2 jaar voor Boston Scientific, Cook, Fujifilm, Medtronic en Olympus.

Geen financiele belangen in biomedische bedrijven

Externe financiering van wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar complicaties van pancreatitis door Bosont Scientific |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

prof. dr. M.J. (Marco) Bruno |

MDL-arts |

- Lecturer en consultant Boston Scientific - Lecturer en consultant Cook Medical - Lecturer 3M - Lecturer Pentax Medical - Consultant Mylan

|

Lid van de Wetenschappelijke Advies Raad (WAR), commissie Care & Cure, Zorginstituut Nederland

Committee member Scientific Committee of United European Gastroenterology (UEG)

ZonMw NutsOhra financiering voor studie naar effect ERCP en papillotomie voorspelt ernstige pancreatitis

Financiering Cook Medical voor investigator initiated studie naar optimalisatie van EUS geleide weefselbiopten (oa pancreaskanker) en training en kwaliteit van ERCP

Financiering Boston Scientific voor investigator initiated studie naar nut en effect van pancreatoscopische behandeling van pacreasstenen bij chronische pancreatitits

Deelname aan verschillende industry initiated ERCP en/of EUS gerelateerde device/accessoires studies

Studie naar infectie prevalentie ERCP scopen gefinancieerd door ministerie van VWS

Studie aangaande endoscoop reiniging gefinancierd door 3M

Studie aangaande endoscoop reiniging gefinancierd door Pentax Medical |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

dr. J.J. (Joost) Nuyttens |

Radiotherapeut |

Onbekend |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

drs. G. (Geertjan) van Tienhoven |

Radiotherapeut oncoloog |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Onderzoek gefinancierd door (onafhankelijk) KWF |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

drs. T.P. (Thomas) Potjer |

Klinisch geneticus i.o. |

PhD student erfelijk pancreascarcinoom / melanoom (betaald) |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

L.J.P.M. (Lieke) Corpelijn |

Verpleegkundig Specialist HPB-Chirurgie |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

M. (Marjan) Mullers MSc |

Diëtist |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

J.E. (Jill) Witvliet-van Nierop MSc |

Diëtist |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Heeft voedingsonderzoek uitgevoerd rondom IRE van pancreascarcinoom (PAN-NUTRIENT studie), gefinancierd door Nationaal Fonds tegen Kanker. De financierder heeft geen belangen bij de resultaten. |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

C.J.M. (Charlotte) van den Bosch MSc |

Diëtist |

Geen nevenfuncties |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

|

L. (Leo) Kwakkenbos |

Ervaringsdeskundige |

Voorzitter WijkNogLeuker

PACO-lid KWF

Lid Voorzittersoverleg Adviesraad KWF

Bestuurslid DPCG (betaald)

Bestuurslid (voorzitter) Living With Hope (Landelijk Patiënten Platform Alvleesklier kanker) (tot januari 2019)

Overige functies zijn onbetaald |

Geen belangen |

Geen acties ondernomen |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door deelname van patiëntvertegewoordigers aan de invitational conference (zie verslag invitational conference bij de aanverwante producten) en deelname van dhr. Leo Kwakkenbos (ervaringsdeskundige) in de werkgroep. De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Living With Hope Foundation.

Methode ontwikkeling

Evidence based

Implementatie

In de verschillende fasen van de richtlijnontwikkeling is rekening gehouden met de implementatie van de richtlijn en de praktische uitvoerbaarheid van de aanbevelingen. Daarbij is uitdrukkelijk gelet op factoren die de invoering van de richtlijn in de praktijk kunnen bevorderen of belemmeren. Het implementatieplan is te vinden bij de aanverwante producten. De werkgroep heeft geen interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld om het toepassen van de richtlijn in de praktijk te volgen en te versterken (zie Indicatorontwikkeling).

Werkwijze

AGREE

Deze richtlijn is opgesteld conform de eisen vermeld in het rapport Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 van de adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwaliteit. Dit rapport is gebaseerd op het AGREE II instrument (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation II; Brouwers 2010), dat een internationaal breed geaccepteerd instrument is. Voor een stap-voor-stap beschrijving hoe een evidence-based richtlijn tot stand komt wordt verwezen naar het stappenplan Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen van het Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Knelpuntenanalyse

Tijdens de voorbereidende fase inventariseerden de voorzitter van de werkgroep en de adviseur de knelpunten. Tevens zijn er knelpunten aangedragen door verschillende partijen via een invitational conference. Een verslag hiervan is opgenomen onder aanverwante producten.

De werkgroep beoordeelde de aanbevelingen uit de eerdere richtlijn Pancreascarcinoom (IKNL 2011) op noodzaak tot revisie. De werkgroep stelde vervolgens een long list met knelpunten op en prioriteerde de knelpunten op basis van:

- Klinische relevantie.

- De beschikbaarheid van (nieuwe) evidence van hoge kwaliteit.

- De te verwachten impact op de kwaliteit van zorg, patiëntveiligheid en (macro)kosten.

Uitgangsvragen en uitkomstmaten

Op basis van de uitkomsten van de knelpuntenanalyse zijn door de voorzitter en de adviseur concept-uitgangsvragen opgesteld. Deze zijn met de werkgroep besproken waarna de werkgroep de definitieve uitgangsvragen heeft vastgesteld. Vervolgens inventariseerde de werkgroep per uitgangsvraag welke uitkomstmaten voor de patiënt relevant zijn, waarbij zowel naar gewenste als ongewenste effecten werd gekeken. De werkgroep waardeerde deze uitkomstmaten volgens hun relatieve belang bij de besluitvorming rondom aanbevelingen, als cruciaal (kritiek voor de besluitvorming), belangrijk (maar niet cruciaal) en onbelangrijk. Tevens definieerde de werkgroep tenminste voor de cruciale uitkomstmaten welke verschillen zij klinisch (patiënt) relevant vonden.

Gebruik van beschikbare evidence Belgische richtlijn Pancreascarcinoom

Het Federaal Kenniscentrum voor de Gezondheidszorg (KCE) en het College voor Oncologie publiceerden in 2017 een selectieve update van hun klinische richtlijn uit 2009 over de diagnose en behandeling van pancreascarcinoom. Het KCE concentreerde zich op drie vragen:

- Wat is de waarde van de volgende onderzoeken bij de diagnose van pancreascarcinoom: ultrasonografie (US), computertomografie (CT), beeldvorming door magnetische resonantie (MRI), endoscopische ultrasonografie (EUS) + fijnenaaldaspiratie (FNA) van de primaire tumor, positronemissietomografiescan (PET-scan), endoscopische retrograde cholangiopancreatografie (ERCP), dosering van tumormarkers en analyse van cystevocht?

- Gaat toediening van een neoadjuvante behandeling met chemotherapie, radiotherapie of beide gepaard met een betere overleving, reseceerbaarheid en kwaliteit van leven (QoL) en met minder complicaties: a) bij patiënten met een reseceerbaar pancreascarcinoom? b) bij patiënten met lokaal invasieve borderlin e reseceerbaar pancreascarcinoom?

- Wat is de optimale behandelingsstrategie bij patiënten met recidief pancreascarcinoom?

De Nederlandse werkgroep beoordeelde de kwaliteit van:

- de strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur;

- het beoordelen van de methodologische kwaliteit van de studies en

- de literatuursamenvattingen

als hoog en heeft er daarom voor gekozen om de literatuursamenvattingen van KCE te gebruiken (na instemming van KCE) bij het formuleren van overwegingen en aanbevelingen voor de modules Diagnostiek, Neoadjuvante behandeling en Behandeling gemetastaseerd pancreascarcinoom. De literatuursamenvattingen, -resultaten, -beoordelingen en -conclusies van de eerder genoemde modules werden door het KCE in het Engels opgesteld en werden niet vertaald voor het gebruik in de huidige richtlijn. Tevens koos de werkgroep ervoor om de literatuurbeschrijvingen en -resultaten (inclusief evidence tabellen) voor enkele modules in het Engels op te stellen om deze eventueel internationaal te kunnen uitwisselen.

Strategie voor zoeken en selecteren van literatuur

De literatuurspecialist zocht aan de hand van specifieke zoektermen naar gepubliceerde wetenschappelijke studies in (verschillende) elektronische databases. Tevens werd aanvullend gezocht naar studies aan de hand van de literatuurlijsten van de geselecteerde artikelen. In eerste instantie werd gezocht naar studies met de hoogste mate van bewijs. De werkgroepleden selecteerden de via de zoekactie gevonden artikelen op basis van vooraf opgestelde selectiecriteria. De geselecteerde artikelen werden gebruikt om de uitgangsvraag te beantwoorden. De databases waarin is gezocht, de zoekstrategie en de gehanteerde selectiecriteria zijn te vinden in de module met desbetreffende uitgangsvraag.

Kwaliteitsbeoordeling individuele studies

Individuele studies werden systematisch beoordeeld, op basis van op voorhand opgestelde methodologische kwaliteitscriteria, om zo het risico op vertekende studieresultaten (risk of bias) te kunnen inschatten. Deze beoordelingen kunt u vinden in de Risk of Bias (RoB) tabellen. De gebruikte RoB instrumenten zijn gevalideerde instrumenten die worden aanbevolen door de Cochrane Collaboration: AMSTAR – voor systematische reviews; Cochrane – voor gerandomiseerd gecontroleerd onderzoek; ACROBAT-NRS – voor observationeel onderzoek; QUADAS II – voor diagnostisch onderzoek.

Samenvatten van de literatuur

De relevante onderzoeksgegevens van alle geselecteerde artikelen werden overzichtelijk weergegeven in evidencetabellen. De belangrijkste bevindingen uit de literatuur werden beschreven in de samenvatting van de literatuur. Bij een voldoende aantal studies en overeenkomstigheid (homogeniteit) tussen de studies werden de gegevens ook kwantitatief samengevat (meta-analyse) met behulp van Review Manager 5.

Beoordelen van de kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs

A) Voor interventievragen (vragen over therapie of screening)

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode. GRADE staat voor ‘Grading Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation’ (zie http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/).

GRADE onderscheidt vier gradaties voor de kwaliteit van het wetenschappelijk bewijs: hoog, redelijk, laag en zeer laag. Deze gradaties verwijzen naar de mate van zekerheid die er bestaat over de literatuurconclusie (Schünemann 2013).

|

GRADE |

Definitie |

|

Hoog |

|

|

Redelijk* |

|

|

Laag |

|

|

Zeer laag |

|

*in 2017 heeft het Dutch GRADE Network bepaalt dat de voorkeursformulering voor de op een na hoogste gradering ‘redelijk’ is i.p.v. ‘matig’

B) Voor vragen over diagnostische tests, schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose

De kracht van het wetenschappelijke bewijs werd eveneens bepaald volgens de GRADE-methode: GRADE-diagnostiek voor diagnostische vragen (Schünemann 2008), en een generieke GRADE-methode voor vragen over schade of bijwerkingen, etiologie en prognose. In de gehanteerde generieke GRADE-methode werden de basisprincipes van de GRADE methodiek toegepast: het benoemen en prioriteren van de klinisch (patiënt) relevante uitkomstmaten, een systematische review per uitkomstmaat, en een beoordeling van bewijskracht op basis van de vijf GRADE criteria (startpunt hoog; downgraden voor risk of bias, inconsistentie, indirectheid, imprecisie, en publicatiebias).

Formuleren van de conclusies

Voor elke relevante uitkomstmaat werd het wetenschappelijk bewijs samengevat in een of meerdere literatuurconclusies waarbij het niveau van bewijs werd bepaald volgens de GRADE methodiek. De werkgroepleden maakten de balans op van elke interventie (overall conclusie). Bij het opmaken van de balans werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten voor de patiënt afgewogen. De overall bewijskracht wordt bepaald door de laagste bewijskracht gevonden bij een van de cruciale uitkomstmaten. Bij complexe besluitvorming waarin naast de conclusies uit de systematische literatuuranalyse vele aanvullende argumenten (overwegingen) een rol spelen, werd afgezien van een overall conclusie. In dat geval werden de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de interventies samen met alle aanvullende argumenten gewogen onder het kopje 'Overwegingen'.

Overwegingen (van bewijs naar aanbeveling)

Om te komen tot een aanbeveling zijn naast (de kwaliteit van) het wetenschappelijke bewijs ook andere aspecten belangrijk en worden meegewogen, zoals de expertise van de werkgroepleden, de waarden en voorkeuren van de patiënt (patient values and preferences), kosten, beschikbaarheid van voorzieningen en organisatorische zaken. Deze aspecten worden, voor zover geen onderdeel van de literatuursamenvatting, vermeld en beoordeeld (gewogen) onder het kopje ‘Overwegingen’.

Formuleren van aanbevelingen

De aanbevelingen geven antwoord op de uitgangsvraag en zijn gebaseerd op het beschikbare wetenschappelijke bewijs en de belangrijkste overwegingen, en een weging van de gunstige en ongunstige effecten van de relevante interventies. De kracht van het wetenschappelijk bewijs en het gewicht dat door de werkgroep wordt toegekend aan de overwegingen, bepalen samen de sterkte van de aanbeveling. Conform de GRADE-methodiek sluit een lage bewijskracht van conclusies in de systematische literatuuranalyse een sterke aanbeveling niet a priori uit, en zijn bij een hoge bewijskracht ook zwakke aanbevelingen mogelijk. De sterkte van de aanbeveling wordt altijd bepaald door weging van alle relevante argumenten tezamen.

Randvoorwaarden (Organisatie van zorg)

In de knelpuntenanalyse en bij de ontwikkeling van de richtlijn is expliciet rekening gehouden met de organisatie van zorg: alle aspecten die randvoorwaardelijk zijn voor het verlenen van zorg (zoals coördinatie, communicatie, (financiële) middelen, menskracht en infrastructuur). Randvoorwaarden die relevant zijn voor het beantwoorden van een specifieke uitgangsvraag maken onderdeel uit van de overwegingen bij de bewuste uitgangsvraag. Meer algemene, overkoepelende, of bijkomende aspecten van de organisatie van zorg worden behandeld in de module Organisatie van Zorg.

Er werden geen interne kwaliteitsindicatoren ontwikkeld om het toepassen van de richtlijn in de praktijk te volgen en te versterken. De werkgroep conformeert zich aan de SONCOS normen en de DICA-DPCA indicatoren.

Kennislacunes

Tijdens de ontwikkeling van deze richtlijn is systematisch gezocht naar onderzoek waarvan de resultaten bijdragen aan een antwoord op de uitgangsvragen. Bij elke uitgangsvraag is door de werkgroep nagegaan of er (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk onderzoek gewenst is om de uitgangsvraag te kunnen beantwoorden. Een overzicht van de onderwerpen waarvoor (aanvullend) wetenschappelijk van belang wordt geacht, is als aanbeveling in de Kennislacunes beschreven (onder aanverwante producten).

Commentaar- en autorisatiefase

De conceptrichtlijn werd aan de betrokken (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd ter commentaar. De commentaren werden verzameld en besproken met de werkgroep. Naar aanleiding van de commentaren werd de conceptrichtlijn aangepast en definitief vastgesteld door de werkgroep. De definitieve richtlijn werd aan de deelnemende (wetenschappelijke) verenigingen en (patiënt) organisaties voorgelegd voor autorisatie en door hen geautoriseerd dan wel geaccordeerd.

Literatuur

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. (2010) AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ, 182(18):E839-42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. PubMed PMID: 20603348; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3001530.

Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen 2.0 (2012). Adviescommissie Richtlijnen van de Raad Kwalitieit. https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/over_deze_site/richtlijnontwikkeling.html

Ontwikkeling van Medisch Specialistische Richtlijnen: stappenplan. Kennisinstituut van Medisch Specialisten.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, et al. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October 2013. The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available from http://gdt.guidelinedevelopment.org/central_prod/_design/client/handbook/handbook.html

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. (2008) Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ, 336(7653):1106-10. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE. Erratum in: BMJ, 336(7654). doi: 10.1136/bmj.a139. Schünemann, Holger J. PubMed PMID: 18483053; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2386626.

Wessels M, Hielkema L, van der Weijden T. (2016) How to identify existing literature on patients' knowledge, views, and values: the development of a validated search filter. J Med Libr Assoc, 104(4):320-324. PubMed PMID: 27822157; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5079497.

Zoekverantwoording

Systematische reviews

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

2010-nov, 2017 Engels |

1 exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/ or ((pancrea* or exocrine) adj3 (fistula or lesion* or anastomosis or mass or neoplasm* or cancer* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma or cystadenocarcinoma or cyst* or tumour* or tumor* or malign*)).ti,ab,kf. (101824) Annotation: Search KCE-rapport: MANAGEMENT OF PANCREATIC CANCER. may 2017 2 surgical procedures, operative/ or minimally invasive surgical procedures/ or Surgery.fs. or (operation* or operative or surger* or surgeries or resection* or whipple*).ti,ab,kf. (2889665) 3 1 and 2 (32234) 4 pancreatectomy/ or pancreaticoduodenectomy/ or pancreaticojejunostomy/ or (pancreaticoduodenectom* or pancreatectom* or pancreaticojejunostom* or pancreaticogastrostom*).ti,ab,kf. (24535) 5 3 or 4 (43909) 7 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (367254) 8 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1874330) 9 exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/rt or exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/dt or "Antineoplastic Agents"/tu or Cytostatic Agents/ or (chemotherap* or radiotherap* or chemoradiotherap* or chemo-radio* or cytostatic* or antineoplastic*).ti,ab,kf. (607722) 10 5 and 9 (5425) 11 exp Radiotherapy, Adjuvant/ or Chemoradiotherapy, Adjuvant/ or "Chemotherapy, Adjuvant"/ (54279) 12 (adjuvant adj3 (radiat* or radiotherap* or chemo*)).ti,ab,kf. (39686) 13 11 or 12 (78959) 14 1 or 4 (112173) 15 13 and 14 (2552) 16 10 or 15 (6129) 17 limit 16 to (english language and yr="2010 -Current") (2740) 18 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (367254) 19 17 and 18 (179) – 149 uniek 20 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1874330) 21 17 and 20 (684) 22 21 not 19 (624) – nog niet

|

212 |

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

(((('pancreas tumor'/exp/mj OR (((pancrea* OR exocrine) NEAR/3 (fistula OR lesion* OR anastomosis OR mass OR neoplasm* OR cancer* OR carcinoma* OR adenocarcinoma OR cystadenocarcinoma OR cyst* OR tumour* OR tumor* OR malign*)):ti,ab))

AND ('minimally invasive surgery'/exp/mj OR surgery:lnk OR operation*:ti,ab OR operative:ti,ab OR surger*:ti,ab OR surgeries:ti,ab OR resection*:ti,ab OR whipple*:ti,ab OR 'pancreas surgery'/exp/mj OR pancreaticoduodenectom*:ti,ab OR pancreatectom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticojejunostom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticogastrostom*:ti,ab))

AND ('pancreas tumor'/exp/mj/dm_dt,dm_rt OR ('antineoplastic agent'/exp/mj OR chemotherap*:ti,ab OR radiotherap*:ti,ab OR chemoradiotherap*:ti,ab OR 'chemo radio*':ti,ab OR cytostatic*:ti,ab OR antineoplastic*:ti,ab)))

OR (('pancreas tumor'/exp/mj OR (((pancrea* OR exocrine) NEAR/3 (fistula OR lesion* OR anastomosis OR mass OR neoplasm* OR cancer* OR carcinoma* OR adenocarcinoma OR cystadenocarcinoma OR cyst* OR tumour* OR tumor* OR malign*)):ti,ab) OR 'pancreas surgery'/exp/mj OR pancreaticoduodenectom*:ti,ab OR pancreatectom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticojejunostom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticogastrostom*:ti,ab)

AND ('cancer adjuvant therapy'/exp/mj OR ((adjuvant NEAR/3 (radiat* OR radiotherap* OR chemo*)):ti,ab))))

AND [english]/lim AND [embase]/lim AND [2010-2017]/py NOT 'conference abstract':it)

AND (('meta analysis'/de OR cochrane:ab OR embase:ab OR psycinfo:ab OR cinahl:ab OR medline:ab OR ((systematic NEAR/1 (review OR overview)):ab,ti) OR ((meta NEAR/1 analy*):ab,ti) OR metaanalys*:ab,ti OR 'data extraction':ab OR cochrane:jt OR 'systematic review'/de) NOT (('animal experiment'/exp OR 'animal model'/exp OR 'nonhuman'/exp) NOT 'human'/exp)) (126) – 63 uniek

(478 mogelijke RCTs nog niet, en nog niet ontdubbeld t.o.v. Medline) |

RCTs

|

Database |

Zoektermen |

Totaal |

|

Medline (OVID)

2010-april, 2018 Engels |

1 exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/ or ((pancrea* or exocrine) adj3 (fistula or lesion* or anastomosis or mass or neoplasm* or cancer* or carcinoma* or adenocarcinoma or cystadenocarcinoma or cyst* or tumour* or tumor* or malign*)).ti,ab,kf. (95878) Annotation: Search KCE-rapport: MANAGEMENT OF PANCREATIC CANCER. may 2017 2 surgical procedures, operative/ or minimally invasive surgical procedures/ or Surgery.fs. or (operation* or operative or surger* or surgeries or resection* or whipple*).ti,ab,kf. (2722392) 3 1 and 2 (30244) 4 pancreatectomy/ or pancreaticoduodenectomy/ or pancreaticojejunostomy/ or (pancreaticoduodenectom* or pancreatectom* or pancreaticojejunostom* or pancreaticogastrostom*).ti,ab,kf. (23022) 5 3 or 4 (41253) 7 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (352443) 8 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1874330) 9 exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/rt or exp Pancreatic Neoplasms/dt or "Antineoplastic Agents"/tu or Cytostatic Agents/ or (chemotherap* or radiotherap* or chemoradiotherap* or chemo-radio* or cytostatic* or antineoplastic*).ti,ab,kf. (569801) 10 5 and 9 (5161) 11 exp Radiotherapy, Adjuvant/ or Chemoradiotherapy, Adjuvant/ or "Chemotherapy, Adjuvant"/ (50498) 12 (adjuvant adj3 (radiat* or radiotherap* or chemo*)).ti,ab,kf. (36941) 13 11 or 12 (73483) 14 1 or 4 (105599) 15 13 and 14 (2407) 16 10 or 15 (5821) 17 limit 16 to (english language and yr="2010 -Current") (2604) 18 (meta-analysis/ or meta-analysis as topic/ or (meta adj analy$).tw. or ((systematic* or literature) adj2 review$1).tw. or (systematic adj overview$1).tw. or exp "Review Literature as Topic"/ or cochrane.ab. or cochrane.jw. or embase.ab. or medline.ab. or (psychlit or psyclit).ab. or (cinahl or cinhal).ab. or cancerlit.ab. or ((selection criteria or data extraction).ab. and "review"/)) not (Comment/ or Editorial/ or Letter/ or (animals/ not humans/)) (367254) 19 17 and 18 (161) 20 (exp clinical trial/ or randomized controlled trial/ or exp clinical trials as topic/ or randomized controlled trials as topic/ or Random Allocation/ or Double-Blind Method/ or Single-Blind Method/ or (clinical trial, phase i or clinical trial, phase ii or clinical trial, phase iii or clinical trial, phase iv or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial or multicenter study or clinical trial).pt. or random*.ti,ab. or (clinic* adj trial*).tw. or ((singl* or doubl* or treb* or tripl*) adj (blind$3 or mask$3)).tw. or Placebos/ or placebo*.tw.) not (animals/ not humans/) (1874330) 21 17 and 20 (613) 22 21 not 19 (564)

= 564 (555 uniek)

|

808

2016-heden: 249

|

|

Embase (Elsevier) |

(((('pancreas tumor'/exp/mj OR (((pancrea* OR exocrine) NEAR/3 (fistula OR lesion* OR anastomosis OR mass OR neoplasm* OR cancer* OR carcinoma* OR adenocarcinoma OR cystadenocarcinoma OR cyst* OR tumour* OR tumor* OR malign*)):ti,ab))

AND ('minimally invasive surgery'/exp/mj OR surgery:lnk OR operation*:ti,ab OR operative:ti,ab OR surger*:ti,ab OR surgeries:ti,ab OR resection*:ti,ab OR whipple*:ti,ab OR 'pancreas surgery'/exp/mj OR pancreaticoduodenectom*:ti,ab OR pancreatectom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticojejunostom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticogastrostom*:ti,ab))

AND ('pancreas tumor'/exp/mj/dm_dt,dm_rt OR ('antineoplastic agent'/exp/mj OR chemotherap*:ti,ab OR radiotherap*:ti,ab OR chemoradiotherap*:ti,ab OR 'chemo radio*':ti,ab OR cytostatic*:ti,ab OR antineoplastic*:ti,ab)))

OR (('pancreas tumor'/exp/mj OR (((pancrea* OR exocrine) NEAR/3 (fistula OR lesion* OR anastomosis OR mass OR neoplasm* OR cancer* OR carcinoma* OR adenocarcinoma OR cystadenocarcinoma OR cyst* OR tumour* OR tumor* OR malign*)):ti,ab) OR 'pancreas surgery'/exp/mj OR pancreaticoduodenectom*:ti,ab OR pancreatectom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticojejunostom*:ti,ab OR pancreaticogastrostom*:ti,ab)

AND ('cancer adjuvant therapy'/exp/mj OR ((adjuvant NEAR/3 (radiat* OR radiotherap* OR chemo*)):ti,ab))))

AND [english]/lim AND [embase]/lim AND [2010-2018]/py NOT 'conference abstract':it)

AND ('clinical trial'/exp OR 'randomization'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp OR 'placebo'/exp OR rct:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR 'randomised controlled trial':ab,ti OR 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR placebo*:ab,ti)

= 551 |

Tabel Exclusie na het lezen van het volledige artikel

|

Auteur en jaartal |

Redenen van exclusie |

|

Zhan 2017 |

Interventie is neoadjuvante therapie |

|

Saung 2017 |

Geen SR |

|

Hurton 2017 |

Protocol, review nog niet gepubliceerd |

|

Khorana 2016 |

Recentere SR beschikbaar |

|

D'Angelo 2016 |

Recentere SR beschikbaar |

|

Yu 2015 |

Recentere SR beschikbaar |

|

Li 2015 |

Geen SR |

|

Sen 2014 |

Geen SR |

|

Liao 2013 |

Recentere SR beschikbaar |

|

Sultana 2012 |

Geen SR |

|

Ren 2012 |

Recentere SR beschikbaar |

|

Lombardi 2012 |

Geen SR |

|

Thomas 2010 |

Geen SR |

|

Iott 2010 |

Recentere SR beschikbaar |